Rheumatoid Arthritis: Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic disease that primarily targets the synovium, leading to synovial inflammation and proliferation, loss of articular cartilage, and erosion of juxtarticular bone. The natural history of the disease is one of progressive joint damage and deformity and, in a sizeable minority, the development of extra-articular manifestations. Fortunately, current therapeutic strategies, particularly if the disease is diagnosed and treated early, result in substantial clinical benefit for most patients.

RA affects approximately 1% of the adult population worldwide and is more common in women (female:male, 3:1) (Table 15–1). Although RA may present at any age, the typical age of onset in women is the late childbearing years; in men, RA develops more often in the sixth to eighth decade.

|

The causes of RA remain elusive. The genetic contribution to RA is substantial, and more than 30 loci conferring risk for RA have been identified thus far. Most genes linked to RA influence immune responses (eg, T cell activation, cytokine signaling). The strongest known association is with alleles of HLADRB1, which encodes the β chain of HLA-DR, a major histocompatiblity class II molecule directly involved in the presentation of antigen to T cells. Allelic variants of HLADRB1 associated with risk for RA encode a similar sequence (amino acids 70–74) known as the “shared epitope.”

Studies of genetic risk reinforce the concept that clinical RA is not a single entity. Most notably, shared-epitope-encoding HLADRB1 alleles confer risk only for RA associated with antibodies to citrullinated protein epitopes (present in approximately 70% of all patients with RA). Citrullination—a post-translational modification of proteins in which arginine residues are converted to citrulline—occurs at sites of inflammation. How patients with RA lose tolerance to citrullinated protein epitopes is uncertain. Interestingly, epidemiologic data links smoking (which induces inflammation and citrullinated proteins in the lung) and periodontitis (which is associated with the citrullination of proteins in periodontal tissues) to risk of developing anti-CCP-positive RA.

Articular Manifestations & Treatment

- Chronic symmetric polyarthritis.

- Symptoms often start in proximal interphalangeal (PIP), metacarpophalangeal (MCP), and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints.

- Serum rheumatoid factor, antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP), or both in 70%.

- Radiographic changes include juxtarticular erosions and joint-space narrowing.

In most patients, RA presents with the insidious onset of pain, stiffness, and swelling in multiple joints over the course of weeks to months. Others, however, may have a fulminant presentation or an onset so insidious that the patient hardly notices. Alternatively, patients may have persistent monoarthritis or oligoarthritis for prolonged periods before manifesting the more typical pattern of polyarticular involvement. Palindromic rheumatism (episodic, self-limited attacks of polyarthritis) may evolve into RA. Rarely, extra-articular features of RA (eg, scleritis) may present before the joint problems occur.

Most patients have fatigue and many have low-grade fevers (≤38°C). Significant weight loss can occur but is uncommon in early onset disease.

Although genetics play a large role in determining risk of RA, most patients have no significant family history.

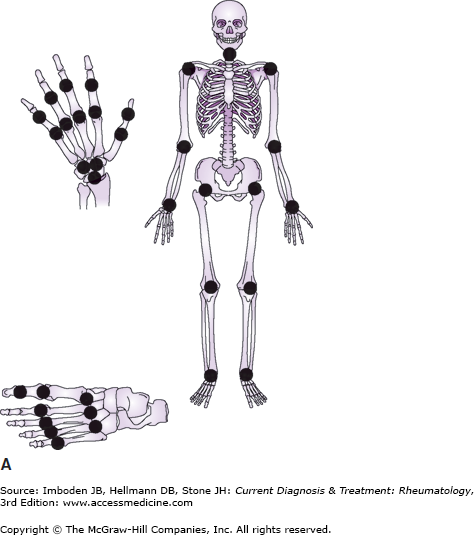

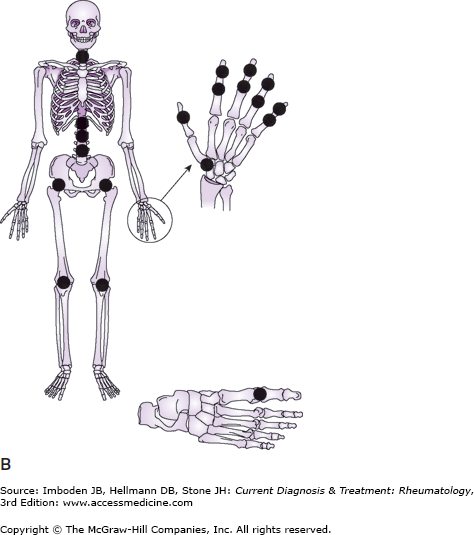

Figure 15–1 illustrates the different joint distribution in RA and osteoarthritis (OA). Most patients with RA report involvement of small joints first, classically the PIP, MCP, and MTP joints, with involvement of large joints occurring later. Symptoms include pain, swelling, and stiffness, with stiffness often dominating. Patients with early disease often complain that rings no longer fit and that they have pain on the balls of the feet while walking to the bathroom in the morning.

Figure 15–1.

The joint distribution of the two most common types of arthritis are compared: rheumatoid arthritis (A) and osteoarthritis (B). Rheumatoid arthritis involves almost all synovial joints in the body. Osteoarthritis has a much more limited distribution. Importantly, rheumatoid arthritis rarely, if ever, involves the distal interphalangeal joints, but osteoarthritis commonly does.

Morning stiffness is a hallmark of inflammatory arthritis and is a prominent feature of RA. Patients with RA are characteristically at their worst upon arising in the morning or after prolonged periods of rest. This stiffness in and around joints often lasts for hours and improves with activity. Routine activities like brushing teeth and combing hair may be very difficult early in the morning, and patients sometimes report running warm water over their hands to “get them working.”

RA can affect any of the synovial joints (Figure 15–1). Most commonly, the disease starts in the MCP, PIP, and MTP joints followed by the wrists, knees, elbows, ankles, hips, and shoulders in roughly that order. Early treatment helps limit the number of joints involved. Of particular importance, RA almost always spares the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (in contrast, these joints are often involved in OA and psoriatic arthritis). Less commonly, and usually only in more advanced cases, RA may involve the temporomandibular, cricoarytenoid and sternoclavicular joints. RA may involve the upper part of the cervical spine, particularly the C1–C2 articulation, but, unlike the spondyloarthropathies, rarely, if ever, involves the rest of the spine.

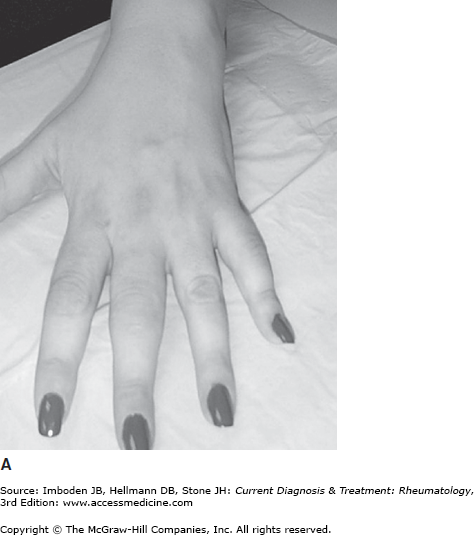

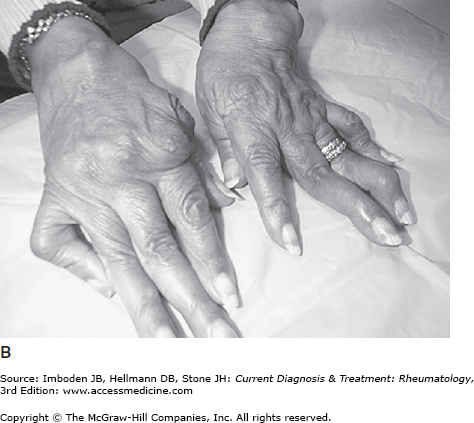

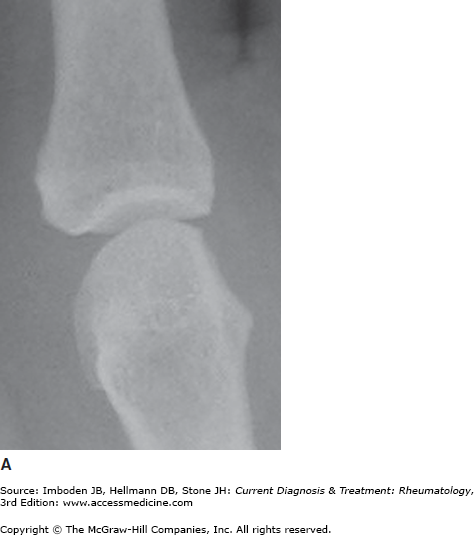

The hands are involved in almost all patients with RA; hand involvement is responsible for a significant portion of the disabilities caused by RA. Typical early disease is shown in Figure 15–2A with the swelling of the PIP joints easily seen. The DIP joints are almost always spared unless the patient also has OA; both diseases are common and can coexist, particularly in elderly patients. Radiographs can detect evidence of articular damage early in the course of RA and long before the appearance of joint deformities (Figure 15–3). Late, established disease all too commonly causes ulnar deviation of the fingers at the MCPs, swan neck deformities (hyperextension of the PIP joints and flexion at the DIP joints; Figure 15–2B), and boutonnière (or buttonhole) deformities (flexion of the PIP joints and hyperextension of the DIP joints). If the clinical disease remains active, hand function slowly deteriorates.

Figure 15–2.

A: A patient with early rheumatoid arthritis. There are no joint deformities, but the soft tissue synovial swelling around the third and fifth proximal inter-phalangeal (PIP) joints is easily seen. B: A patient with advanced rheumatoid arthritis with severe joint deformities including subluxation at the metacarpophalangeal joints and swan-neck deformities (hyperextension at the PIP joints).

Figure 15–3.

Progressive destruction of a metacarpophalangeal joint by rheumatoid arthritis. Shown are sequential radiographs of the same second metacarpophalangeal joint. A: The joint is normal 1 year prior to the development of rheumatoid arthritis. B: Six months following the onset of rheumatoid arthritis, there is a bony erosion adjacent to the joint and joint-space narrowing. C: After 3 years of disease, diffuse loss of articular cartilage has led to marked joint-space narrowing.

Wrists are involved in most patients with RA. Early in the course of the disease, synovial proliferation in and around the wrists can compress the median nerve, causing carpal tunnel syndrome. Chronic synovitis can lead to radial deviation of the wrist and, in severe cases, to volar subluxation. Synovial proliferation of the wrist can invade extensor tendons, lead to rupture and abrupt loss of function of individual fingers.

The feet, particularly the MTP joints, are involved early in almost all cases of RA and are second only to hand involvement in terms of the problems they cause. Radiographic erosions occur at least as early in the feet as in the hands. Subluxation of the toes at the MTP joints is common and leads to the dual problem of skin ulceration on the top of the toes and painful ambulation because of loss of the cushioning pads that protect the heads of the metatarsals. Symptoms from MTP subluxation can respond to orthotics but may require surgery.

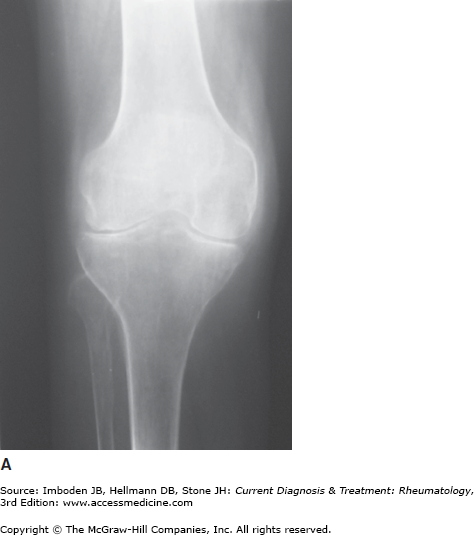

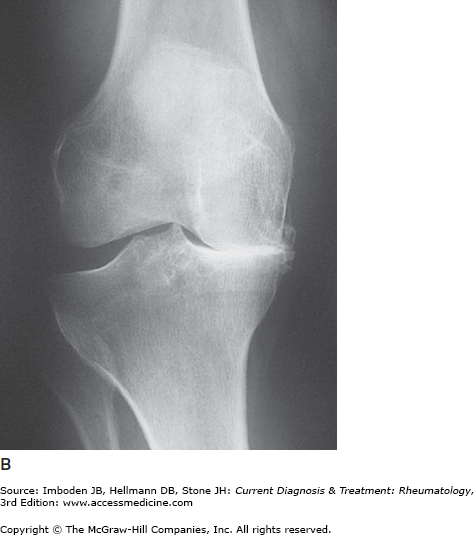

Involvement of large joints (knees, ankles, elbows, hips, and shoulders) is common but generally occurs somewhat later than small joint involvement. Characteristically, the entire joint surface is involved in a symmetric fashion. Therefore, RA is not only symmetric from one side of the body to the other but is also symmetric within the individual joint. In the case of the knee (Figure 15–4A), the medial and lateral compartments are both severely narrowed in RA, whereas OA usually involves only one compartment (Figure 15–4B). Total joint replacements of hips and knees can dramatically improve function and quality of life and should be considered in patients with severe mechanical damage.

Figure 15–4.

The radiographic features of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis are compared with regard to large joint involvement. A: Symmetric loss of cartilage space that is typical of inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis. Note that both the medial and lateral compartments are severely narrowed. Despite this severe narrowing, there is very little in the way of subchondral sclerosis or osteophyte formation since these repair mechanisms are generally shut off in active rheumatoid arthritis. B: Complete loss of the cartilage in the medial joint compartment with significant subchondral sclerosis and osteophyte formation. The lateral compartment in this patient is not involved. These features are typical of osteoarthritis.

Synovial cysts present as fluctuant masses around involved joints (large or small). Synovial cysts from the knee are perhaps the best examples of this phenomenon. The inflamed knee produces excess synovial fluid that can accumulate posteriorly because of a one-way valve effect between the knee joint and the popliteal space (popliteal or Baker cyst). Baker cysts cause problems by compressing the popliteal nerve, artery, or veins; by dissecting into the tissues of the calf (usually posteriorly); and by rupturing into calf. Dissection usually produces only minor symptoms such as a feeling of fullness. Rupture of a Baker cyst, however, leads to extravasation of the inflammatory contents into the calf, producing significant pain and swelling that may be confused with thrombophlebitis (pseudothrombophlebitis syndrome). Ultrasonography of the popliteal fossa and calf is useful to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out thrombophlebitis, which may be precipitated by popliteal cysts. Short-term treatment of popliteal cysts usually involves injecting the knee anteriorly with glucocorticoids to interrupt the inflammatory process.

RA commonly affects the cervical spine (especially the C1–C2 articulation) but spares the thoracic, lumbar and sacral components of the spine. As with RA elsewhere, bony erosions and ligament damage can occur in this area and can lead to subluxation. Most often, subluxation is minor, and patients and caregivers need only be cautious and avoid forcing the neck into positions of flexion. Occasionally, C1–C2 subluxation is severe and requires complex surgical intervention in an attempt to prevent compromise of the cervical cord and, in some cases, death.

Wherever synovial tissue exists, RA can cause problems; the temporomandibular, cricoarytenoid, and sternoclavicular joints are examples. The cricoarytenoid joint is responsible for abduction and adduction of the vocal cords. Involvement of this joint may lead to a feeling of fullness in the throat, to hoarseness, or rarely to a syndrome of acute respiratory distress with or without stridor when the cords are essentially frozen in a closed position. In this latter situation, emergent tracheotomy may be lifesaving.

Anemia of chronic disease is seen in most patients with RA, and the degree of anemia is proportional to the activity of the disease. Therapy that controls the disease results in normalization of the hemoglobin. White blood cell counts may be elevated, normal or, in the case of Felty syndrome, profoundly depressed. Thrombocytosis is common when RA is active, with platelet counts returning to normal as the inflammation is controlled.

An acute phase response, reflected in elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR) and serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), often parallels the activity of the disease. Persistent elevation of ESR and CRP portends a poor prognosis, both in terms of joint destruction and mortality.

Autoantibodies occur in most patients. The autoantibodies most specific for RA are directed against citrullinated protein epitopes and are detected by use of synthetic cyclic citrullinated peptides. These anti-CCP antibodies are present in 60–70% of patients with RA at diagnosis, are 90–98% specific for RA, are often present in the serum years before RA is diagnosed, and correlate strongly with erosive disease. The first autoantibody to be associated with RA was rheumatoid factor, an autoantibody directed against the constant (Fc) region of IgG. Rheumatoid factor is positive in about 50% of cases at presentation and an additional 20–35% of cases become positive in the first 6 months after diagnosis. Rheumatoid factor has an unfortunate name because it is not unique to RA and occurs in many other diseases, particularly those characterized by chronic stimulation of the immune system (Table 15–2). In RA, the presence of rheumatoid factor is associated with more severe articular disease, and essentially all patients with the extra-articular features are seropositive for rheumatoid factor. RA is associated with multiple other autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies (ANA; ∼30% of patients) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), particularly of the perinuclear type (∼30% of patients).

|

Synovial fluid in RA is inflammatory; white blood cell counts typically range from 5000/mcL to 50,000/mcL with approximately two-thirds of the cells being neutrophils. No synovial fluid findings are pathognomonic of RA.

Radiographs of rheumatoid joints may demonstrate juxta-articular demineralization and bony erosions. Early erosions typically occur at the margins of the joint (“marginal erosions”) where synovium directly contacts bone and there is no articular cartilage (Figure 15–3). Cartilage loss leads to joint-space narrowing which, in RA, is uniform (in contrast to OA, which cause irregular narrowing) (Figures 15–3 and 15–4). Radiographs of the hands and feet are an important component of the evaluation of the patient with RA and should be obtained at the outset and then assessed thereafter at intervals of a year or more. Radiographs are often normal early in the course of RA; the presence of erosions at presentation is associated with a more aggressive course. Erosions of MTPs may be detected prior to radiographic changes in the hands. Progression of erosions and joint-space narrowing is an indication of ongoing joint damage. Radiographs are not sensitive for early changes in hips, knees, elbows and other large joints but can be very helpful in the assessment of damage in these joints in chronic disease. Radiographs of the cervical spine in flexion and extension can demonstrate C1–C2 subluxation; MRI is the preferred imaging technique to evaluate possible impingement on the spinal cord.

Unfortunately, there is no one single finding on physical examination or laboratory testing that is diagnostic of RA. Instead, the diagnosis of RA is a clinical one, requiring a collection of historical and physical features, as well as an alert and informed clinician. While a history of arthralgias is important, the diagnosis of RA requires the objective evidence of joint inflammation (swelling or warmth or both) on examination.

In 1987 the American College of Rheumatology provided classification criteria that, although not designed specifically for the purpose, were widely used as an aid to diagnosis of RA (Table 15–3). The first five criteria are clinical; only the last two criteria require laboratory tests or radiographs. Of note the first four criteria need to be present for at least 6 weeks before a diagnosis of RA can be made. This time requirement was imposed because a number of conditions, most notably viral-related syndromes, can cause self-limited polyarthritis (generally of 2–4 week duration) indistinguishable from RA (Table 15–4). The 1987 classification criteria perform well for the diagnosis of established RA but are of limited usefulness for the diagnosis of early disease and do not incorporate testing for anti-CCP antibodies, which are highly specific for RA. In 2010 the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism collaborated to develop new classification criteria with the explicit goal of improved sensitivity and specificity for early RA. The 2010 classification criteria, which require synovitis in at least one joint and the absence of a more plausible alternative diagnosis, use a composite scoring system based on four domains: (1) the number and site of affected joints; (2) the presence and level of anti-CCP antibodies and rheumatoid factor; (3) acute phase reactants (ESR and CRP); (4) duration of symptoms for more than 6 weeks (Table 15–4).

|

| Criteriaa,b | Score |

|---|---|

| A. Joint involvement | |

| 1 large joint | 0 |

| 2–10 large joints | 1 |

| 1–3 small joints | 3 |

| >10 joints (at least 1 small joint) | 4 |

| B. Serology | |

| Negative RF and anti-CCP | 0 |

| Low-positive RF or anti-CCP | 2 |

| High-positive RF or anti-CCP | 3 |

| C. Acute-phase reactants | |

| Normal CRP and ESR | 0 |

| Abnormal CRP or ESR | 1 |

| D. Duration of symptoms | |

| <6 weeks | 0 |

| ≥6 weeks | 1 |

Many diseases can mimic RA (Table 15–5). Accurate diagnosis of early RA can be particularly challenging. Acute viral syndromes, especially acute hepatitis B, erythrovirus (parvovirus B19), rubella (infection or vaccination), and Epstein-Barr virus can produce a polyarthritis that mimics early RA but is self-limited, usually resolving over 2–4 weeks. Atypical early presentations of RA can be difficult to distinguish from the initial stages of undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis; a targeted history and examination may elucidate associated clinical features of these diseases, such as rash, oral ulcers, nail changes, dactylitis, and urethritis. There can be considerable clinical and serologic overlap between RA and systemic lupus erythematosus. Anti-Jo-1-positive polymyositis can present with an erosive polyarthritis, a positive test for serum rheumatoid factor, and minimal muscle symptoms. Chronic infection with hepatitis C commonly causes polyarthralgias (less often, polyarthritis) in a joint distribution similar to that of RA as well as serum rheumatoid factor (but not anti-CCP antibodies or radiographic erosions); RA and hepatitis C can coexist, causing diagnostic uncertainty. In the elderly with abrupt onset of polyarthritis, remitting seronegative symmetric synovitis with pitting edema (RS3PE), paraneoplastic syndromes, and drug-induced lupus should be considered. The diagnosis of chronic, deforming RA is usually obvious. However, chronic tophaceous gout can mimic severe nodular RA, and chondrocalcinosis can cause a destructive “pseudorheumatoid” arthropathy of the wrists and MCPs. Finally, OA with severe deformities of the hands from bony proliferation of the DIP and PIP joints (Heberden and Bouchard nodes) may confuse inexperienced clinicians; the keys here are DIP joint involvement and the bony, instead of soft tissue, joint abnormalities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree