Abstract

Objective

To study work re-entry by patients having suffered a stroke at least 3 years previously.

Patients and methods

This was a retrospective survey in which a questionnaire was administered to all patients admitted after a first stroke to the “La Tour de Gassies” Centre for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (CPRM) in France between January 2005 and June 2007 and who were in work at the time of the incident.

Results

Fifty-six of the 72 included patients (78%) completed and returned the survey questionnaire. The mean age at the time of the stroke was 48.3 ± 10.1. Eighteen (32.1%) of the 56 patients returned to work after their stroke (mean post-stroke time interval: 19.2 ± 13.4 months). Negative prognostic factors for a return to work were living alone, the presence of severe functional impairment and the presence of speech disorders. Positive prognostic factors included specific, professional support and early involvement of the occupational physician. Patients who resumed driving were more likely to return to work and there was a positive correlation between the time to work re-entry and the time to resumption of driving.

Conclusion

Close cooperation between occupational health services and CPRM appears to be necessary to speed the return to work by stroke patients.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la réinsertion socioprofessionnelle de patients victimes d’un accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) interrogés à distance de leur AVC.

Patients et méthode

Enquête rétrospective avec administration d’un questionnaire auprès de tous les patients hospitalisés au Centre de médecine physique et de réadaptation de la Tour de Gassies entre janvier 2005 et juin 2007 dans les suites d’un premier AVC et qui travaillaient au moment de la survenue de leur accident.

Résultats

Cinquante-six des 72 patients inclus (78 %), âgés en moyenne de 48,3 ± 10,1 ans au moment de l’AVC, ont répondu à l’enquête. Dix-huit (32,1 %) d’entre eux ont repris une activité professionnelle, avec un délai post-AVC moyen de 19,2 ± 13,4 mois. Les facteurs pronostiques péjoratifs de retour au travail sont le fait de vivre seul, la gravité des séquelles fonctionnelles et l’existence de troubles du langage. À l’inverse, un accompagnement professionnel spécifique et l’implication précoce du médecin du travail semblent augmenter les chances de réinsertion. Par ailleurs, il existe une corrélation positive entre le délai de réinsertion professionnelle et le délai de reprise de la conduite.

Conclusion

Une collaboration étroite semble nécessaire entre les services de santé au travail et les services de médecine physique et de réadaptation pour améliorer la réinsertion professionnelle de ces patients.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Stroke is a major public health issue in France and worldwide. The neurological and functional consequences can be severe; in France, stroke is currently the leading cause of acquired handicap in adults. Furthermore, stroke has a very high socio-economic cost. It generates direct healthcare costs (hospitalization, treatments, rehabilitation) and indirect economic costs related to the impact of sequelae on work productivity. Although the incidence of stroke increases with age, this affliction also affects adults of working age because about a quarter of stroke victims are under the age of 65 (around 32,500 cases a year in France) and about 15% of the patients are under 55 (around 19,500 cases a year in France) . The issue of the patients’ professional future should be addressed early on in rehabilitation and retraining programmes.

In the literature, several studies have focused on the return to work after a stroke ( Table 1 ). The return to work rates range from 14 to 73% and the post-stroke time interval to work re-entry also varies. The few French studies have shown rates of return to work between 59 and 73% . However, several factors make it difficult to compare these various studies. Firstly, there is significant inter-study heterogeneity in terms of methodologies, study populations (age, type of stroke, etc.), patient recruitment procedures and the length of follow-up. Secondly, work re-entry depends on country-specific social and cultural particularities of the healthcare system and patient support procedures.

| Year of publication | Author [reference] | Country | Sample size | Return to work rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Kotila | Finland | 58 | 55 |

| 1985 | Howard | United States | 379 | 19 |

| 1990 | Black-Schaffer | United States | 79 | 49 |

| 1991 | Bergmann | Germany | 204 | 14 |

| 1993 | Saeki | Japan | 230 | 58 |

| 1994 | Ferro | Portugal | 184 | 73 |

| 1997 | Hsieh | Taiwan | 248 | 58 |

| 1997 | Pradat-Diehl | France | 22 | 59 |

| 1998 | Neau | France | 63 | 73 |

| 1999 | Wozniak | United States | 156 | 51 |

| 2000 | Teasell | Canada | 64 | 20 |

| 2002 | Leys | France | 265 | 65 |

| 2003 | Vestling | Sweden | 120 | 41 |

| 2004 | Varona | Spain | 240 | 53 |

| 2008 | Glozier | New Zealand | 210 | 53 |

| 2009 | Busch | United Kingdom | 266 | 35 |

| 2009 | Gabriele | Germany | 60 | 27 |

| 2010 | Saeki | Japan | 253 | 55 |

| 2011 | Tanaka | Japan | 335 | 30 |

Literature reviews have listed several factors that are likely to influence the return to work rate : these include demographic factors (such as age and gender), medical parameters (such as the type and site of the stroke and the type and gravity of the sequelae) and social factors (such as the educational level and the socioprofessional category). However, the true impact of these factors on the return to work is subject to debate. Furthermore, the question arises as to the role of the occupational physician and the organizations that seek to promote work re-entry for brain-damaged people in France.

We performed a retrospective survey of patients hospitalized in a French Centre for Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (CPRM) after a first stroke. The study’s primary objective was to describe the professional outcome in these patients at least 3 years after their stroke. This corresponds to the maximum duration of sick leave in France and is long enough to reasonably expect to see a return to work. The study’s secondary objective was to identify factors likely to promote or hinder a return to work in this population.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Study population

We included consecutive first-stroke patients aged between 18 and 65 and having been admitted to the “La Tour de Gassies” CPRM (Bruges, France) between January 2005 and June 2007. All the patients were in work at the time of their stroke. Retired or unemployed patients were excluded, as were patients who died following their stroke.

1.2.2

Data collection

The following data were collected from the patients’ medical records: family name, first name, gender, age, family situation at the time of the stroke, date of the stroke, type of stroke (ischaemic, haemorrhagic or cerebromeningeal), site of brain damage (right and/or left hemisphere or posterior fossa), main impairments on discharge from the CPRM (any mentions of motor, sensory, cognitive, language or visual disorders or post-stroke epilepsy), Barthel Index on discharge and any mentions of post-stroke contact (in writing or by telephone) between the CPRM staff and the occupational physician.

The questionnaire was posted at least 3 years after the stroke to all patients meeting the inclusion criteria. It was filled out by the patient, with help from a friend, family member or carer if required. In the absence of a reply 2 weeks after the postage date, patients were invited to complete the questionnaire by telephone. The following items of information were collected: current family situation, educational level (according to the French National Statistics Office’s [INSEE] official nomenclature dating from 1967), current level of independence in activities of daily living (including Rankin’s modified score), resumption of driving or not and, as appropriate, the corresponding date.

The questionnaire was divided in two sections. The first section concerned the characteristics of the job that patient had held at the time of his/her stroke. To describe the socioprofessional category, we used level 1 of the official PCS 2003 nomenclature. We also divided the patients into two groups: those with an administrative or office job (referred to as “white collar” jobs) and those with a mainly manual activity (“blue collar” jobs). The other questions covered the type of employment contract, the job title, the time in the work position, the time with the employer and the total number of employees in the company. The second section of the questionnaire concerned the patient’s post-stroke professional outcome. For patients who had returned to work, we asked for the date of return, any adjustments made to the work environment or working hours and whether there had been a permanent change of job or employer. A patient who had not returned to work had to specify his/her new status (invalidity, retirement, training or retraining, etc.) and the medical reasons that, in his/her opinion, had prevented a return to work. We then asked whether the patient had been officially accredited as a handicapped worker (“RQTH” status), had received support from an organization specializing in work re-entry and/or had consulted his/her occupational physician before a prospective return to work (pre-return consultation).

1.2.3

Analytical methods

We first described the study population’s sociodemographic and medical characteristics. We also studied the patients’ employment status before the stroke and at the time of the questionnaire. Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD or the median ± range. Qualitative variables were expressed as the frequency and the percentage.

Secondly, we sought to establish whether or not there was a relationship between the return to work and the patients’ various quantitative and qualitative variables. To this end, we divided our sample into two groups (those who had returned to work after the stroke and those who had not) and compared them for each variable by using non-parametric tests and calculating the P -value. The Mann-Whitney test was used for intergroup comparisons of mean values, whereas Fisher’s exact test was applied to qualitative data. Lastly, we calculated a correlation coefficient to test for a putative relationship between the post-stroke time to work re-entry and the post-stroke time to resumption of driving.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Characteristics of the study population

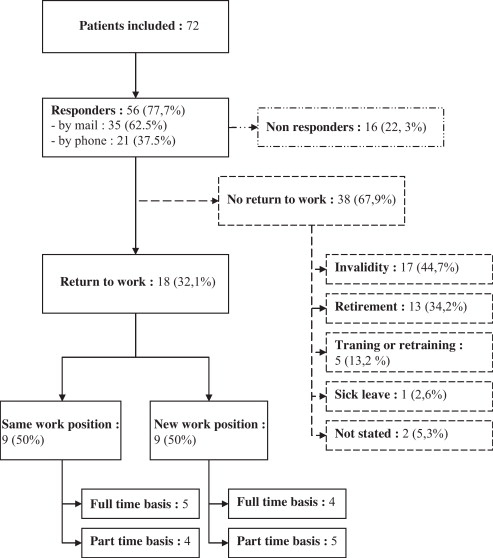

The disposition of the study population is shown in Fig. 1 . Of the 72 patients who received the questionnaire, 56 (77.8%) replied (35 men and 21 women; gender ratio: 1.67). The mean age at the time of the stroke was 48.3 ± 10.1 (median: 51.5). Thirty-three patients (58.9%) were aged over 50 and 22 (39.3%) were over 55. Eleven patients (19.6%) lived alone and 45 (80.4%) lived with a partner. The family situation had changed after the stroke in three cases (one patient had divorced and two who used to live with partners were now living alone).

Twenty-eight subjects (50%) had suffered an ischaemic stroke, 20 (35.7%) had suffered a haemorrhagic stroke and eight (14.3%) had suffered a cerebromeningeal haemorrhage. Twenty-three patients (41.1%) displayed damage to the right hemisphere, 17 (30.3%) had left hemisphere damage, six (10.7%) had damage to both hemispheres and 10 (17.9%) had damage to the posterior fosse. The medical records mentioned motor sequelae in 45 cases (80.4%) and sensory sequelae in 27 cases (48.2%). Cognitive disorders were mentioned in 20 cases (35.7%), language disorders were mentioned in 21 cases (37.5%) and visual sequelae were mentioned in 12 cases (21.4%). Fourteen patients suffered from post-stroke epilepsy (25%). The mean duration of post-stroke hospitalization at the “La Tour de Gassies” CPRM was 195.7 ± 162.5 days (median: 145.5 days). The mean Barthel index on discharge from the CPRM was 86.4 ± 16.4 (median: 90). The mean modified Rankin score at the time of questionnaire administration was 2.3 ± 1 (median: 2). These sociodemographic and medical data are further described in Table 2 .

| Total ( n = 56) | Return to work ( n = 18) | No return to work ( n = 38) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (total population) | n | % | n | % | P | |

| Age, mean (±SD), year | 48.3 | (±10.1) | 44.8 | (±11.8) | 49.9 | (±8.8) | 0.17 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 35 | 62.5 | 11 | 31.4 | 24 | 68.6 | 0.55 |

| Female | 21 | 37.5 | 7 | 33.3 | 14 | 66.7 | |

| Educational level | |||||||

| Junior high | 13 | 23.2 | 2 | 15.4 | 11 | 84.6 | 0.12 |

| Vocational | 22 | 39.3 | 7 | 31.8 | 15 | 68.2 | 0.60 |

| High school | 21 | 37.5 | 9 | 42.9 | 12 | 57.1 | 0.15 |

| Family situation | |||||||

| Married/with a partner | 45 | 80.4 | 18 | 40.0 | 27 | 60.0 | 0.01 a |

| Single | 11 | 19.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 100.0 | |

| Type of stroke | |||||||

| Ischaemic | 28 | 50.0 | 9 | 32.1 | 19 | 67.9 | 0.61 |

| Haemorrhagic | 20 | 35.7 | 8 | 40.0 | 12 | 60.0 | 0.26 |

| Cerebromeningeal | 8 | 14.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 7 | 87.5 | 0.19 |

| Stroke site | |||||||

| Right hemisphere | 23 | 41.1 | 8 | 34.8 | 15 | 65.2 | 0.47 |

| Left hemisphere | 17 | 30.3 | 6 | 35.3 | 11 | 64.7 | 0.49 |

| Both hemispheres | 6 | 10.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.36 |

| Posterior fossa | 10 | 17.9 | 3 | 30.0 | 7 | 70.0 | 0.60 |

| Impairments | |||||||

| Motor disorders | 45 | 80.4 | 13 | 28.9 | 32 | 71.1 | 0.24 |

| Sensory disorders | 27 | 48.2 | 8 | 29.6 | 19 | 70.4 | 0.46 |

| Language disorders | 21 | 37.5 | 3 | 14.3 | 18 | 85.7 | 0.02 a |

| Cognitive disorders | 20 | 35.7 | 6 | 30.0 | 14 | 70.0 | 0.52 |

| Memory disorders | 3 | 5.4 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | – |

| Psychomotor slowing | 12 | 21.4 | 4 | 33.3 | 8 | 66.7 | – |

| Syndrome frontal | 5 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 100.0 | – |

| Visual disorders | 12 | 21.4 | 3 | 25.0 | 9 | 75.0 | 0.41 |

| Lateral homonymous hemianopsia | 8 | 14.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 7 | 87.5 | – |

| Oculomotor disorders | 4 | 7.1 | 2 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 | – |

| Epilepsy | 14 | 25.0 | 4 | 28.6 | 10 | 71.4 | 0.51 |

| Level of disability | |||||||

| Barthel Index, mean (±SD), out of 100 | 86.4 | (±16.4) | 95.6 | (±5.3) | 82.1 | (±18.0) | < 0.001 a |

| Rankin score, mean (±SD), out of 6 | 2.3 | (±1.0) | 1.4 | (±0.6) | 2.7 | (±0.9) | < 0.001 a |

| Length of hospitalization in the CPRM (days), mean (±SD) | 195.7 | (±162.5) | 144.3 | (±112.5) | 219.9 | (±177.6) | 0.17 |

1.3.2

Professional situation at the time of the stroke

These data are detailed in Table 3 . Twenty-two patients (39.3%) were employees and 12 (21.4%) were workers. Twenty-two patients (39.3%) had a “white collar” job and 34 (60.7%) had a “blue collar” job. The mean time in the work position was 11.7 ± 10.6 years (median: 7.5) and the mean time with the employer was 16.1 ± 11.7 years (median: 14.5). Lastly, 19 patients (33.9%) worked in very small companies (with fewer than 10 employees), six worked in small companies (between 10 and 49 employees) and 29 (51.8%) worked in medium-sized or large companies (50 or more employees).

| Total ( n = 56) | Return to work ( n = 18) | No return to work ( n = 38) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (total population) | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Socioprofessional category | |||||||

| Worker | 12 | 21.4 | 3 | 25.0 | 9 | 75.0 | 0.41 |

| Employee | 22 | 39.3 | 7 | 31.8 | 15 | 68.2 | 0.60 |

| Intermediate profession | 5 | 8.9 | 1 | 20.0 | 4 | 80.0 | 0.48 |

| Manager, liberal professions | 8 | 14.3 | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 0.22 |

| Craftsperson, tradesperson, company owner | 9 | 16.1 | 3 | 33.3 | 6 | 66.7 | 0.61 |

| Type of job | |||||||

| “Blue collar” | 34 | 60.7 | 8 | 23.5 | 26 | 76.5 | 0.08 |

| “White collar” | 22 | 39.3 | 10 | 45.5 | 12 | 54.5 | |

| Company size | |||||||

| Very small company (fewer than 10 employees) | 19 | 33.9 | 7 | 36.8 | 12 | 63.2 | 0.46 |

| Small company (10 to 49 employees) | 6 | 10.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 0.36 |

| Medium-sized or large company (50 employees or more) | 29 | 51.8 | 10 | 34.5 | 19 | 65.5 | 0.54 |

| Not stated | 2 | 3.6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Time in the work position (years), mean (±SD) | 11.7 | (±10.6) | 11.4 | (±11.8) | 11.9 | (±10.2) | 0.79 |

| Time with the employer (years), mean (±SD) | 16.1 | (±11.7) | 17.0 | (±12.0) | 15.6 | (±11.7) | 0.69 |

1.3.3

Professional situation at the time of the survey

Eighteen patients (32.1%) had returned to work after their stroke. There were 11 men and seven women (gender ratio: 1.57) with a mean age at the time of the stroke at 44.8 ± 11.8 (median: 46). The mean time interval between the stroke and the return to work was 19.2 ± 13.4 months (median: 13). Nine of the 18 patients (50%) had returned to the same work position (including four initially on a part-time basis). The other nine patients changed jobs (five with the same employer and four with a new employer) and five of them initially returned to work on a part-time basis.

Of the 38 patients who had not returned to work, 17 (44.7%) had been granted permanent invalidity benefit, 13 (34.2%) had retired, five (13.2%) were in training or professional retraining, one was still on sick leave and two had not replied to this question. Thirty-four patients cited one or more medical causes as the main obstacle to work re-entry: motor sequelae (76.5%), cognitive and/or language disorders (61.8%), fatigue (23.5%), epilepsy (8.8%) and depression (2.8%).

Sixteen of the respondees (28.6%) had been accredited as handicapped workers (RQTH status). Seventeen (30.3%) underwent an early social and occupational insertion approach with COMETE France. Five subjects (8.9%) had joined the UEROS Aquitaine network (Evaluation Unit of Retraining and Social/vocational Orientation). Fifteen patients (26.8%) had consulted their occupational physician before a prospective return to work (pre-return consultation). In 17 cases (30.3%) there had been an exchange between the occupational physician and staff at the “La Tour de Gassies” CPRM. Ten of the latter (58.8%) had been able to return to work. Twenty-eight of the 50 subjects (56%) who drove regularly before their stroke were able to resume driving, with a mean post-stroke time interval of 18.3 ± 11.9 months (median: 16). These data are further described in Table 4 .

| Total ( n = 56) | Return to work ( n = 18) | No return to work ( n = 38) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (total population) | n | % | n | % | P | |

| RQTH accreditation | 16 | 28.6 | 7 | 43.8 | 9 | 56.2 | 0.19 |

| Professional support | 19 | 33.9 | 11 | 57.9 | 8 | 42.1 | 0.004 a |

| COMETE | 14 | 25.0 | 9 | 64.3 | 5 | 35.7 | – |

| UEROS | 2 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 | – |

| COMETE and UEROS | 3 | 5.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 | – |

| Contact between the occupational physician and CPRM staff | 17 | 30.3 | 10 | 58.8 | 7 | 41.2 | 0.007 a |

| Pre-return consultation | 15 | 26.8 | 8 | 53.3 | 7 | 46.7 | 0.09 |

| Resumption of motor vehicle driving | 26 | 46.4 | 15 | 57.7 | 11 | 42.3 | < 0.001 a |

| Time to resumption of motor vehicle driving (months), mean (±SD) | 18.3 | (±11.9) | 15.0 | (±8.9) | 22.9 | (±14.2) | 0.10 |

1.3.4

Relationships between the return to work and the variables studied

We did not observe significant differences between the two groups (i.e. those who had returned to work and those who had not) in terms of age, gender and educational level. In contrast, we noticed that subjects who were living alone at the time of their stroke returned to work significantly less frequently than those who lived with a partner ( P = 0.01). A return to work was not significantly associated with the type of stroke, the site in the brain or a mention of motor, sensory, cognitive, visual disorders or epilepsy in the patient’s medical records on discharge from the CPRM. In contrast, the return to work rate was significantly lower when language disorders were noted ( P = 0.02). Likewise, we found that the subjects having returned to work had a significantly higher Barthel index ( P < 0.001) and a significantly lower modified Rankin score ( P < 0.001) than those who did not ( Table 2 ).

Concerning the job held at the time of the stroke, we did not find any statistically significant relationships between the return to work rate and the socioprofessional category, the company size, the time in the work position or with the employer. There was a trend towards a higher return to work rate for “white collar” jobs than for “blue collar” jobs ( P = 0.08) ( Table 3 ).

In contrast, the return to work rate was significantly higher for subjects having received specific professional support ( P = 0.004) and for those whose case had been discussed by the occupational physician and the CPRM staff ( P = 0.007). Although the likelihood of a return to work tended to be higher for patients having consulted their occupational physician before a prospective return to work, the difference was not significant ( P = 0.09).

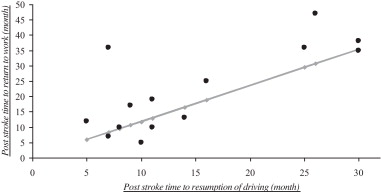

Lastly, patients having resumed driving had a significantly higher return to work rate than those who had not resumed driving ( P < 0.001) ( Table 4 ). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation (correlation coefficient: 1.18) between the post-stroke time to return to work and the post-stroke time to resumption of driving ( P = 0.001) ( Fig. 2 ).

1.4

Discussion

Our study’s primary objective was to describe the professional outcomes of stroke victims at least 3 years after their attack. We found that 32.1% of the study population had returned to work. This percentage agrees with the international literature (with values ranging from 14 to 73%) but is lower than those reported in French studies. In Neau et al.’s study of an initial population of 71 patients with at least 1 year of post-stroke follow-up, the return to work rate (estimated from the 63 surveyed patients) was 73%. Leys et al. found a rate of 65% with an initial population of 287 patients (265 survivors) and an average of 3 years of post-stroke follow-up. There are two possible explanations for these differences.

Firstly, the studies by Neau et al. and Leys et al. were conducted in a neurology department, whereas our study was performed on patients who had all been hospitalized in a CPRM. In France, stroke patients are sent to a CPRM when they suffer from major neurological and functional sequelae, whereas other patients are discharged directly to home. With reference to the modified Rankin score, one can see that only 25% of our patients had a score of 1 or less at the time when the questionnaire was filled out. In contrast, this proportion was 65% and 78% in the populations studied by Neau et al. and Leys et al. , respectively. Furthermore, the mean Rankin score in the latter study was 1.1 versus 2.3 in our survey. One other French study looked at a population of patients hospitalized in a CPRM ; although the return to work rate was 59% at 3 years post-stroke, the study population was small ( n = 22) and included unemployed people and students.

Secondly, the patients included by Leys et al. and Neau et al. were younger (with mean ages of 35.8 and 36.0, respectively) than those in our study (48.3). This is because patients over the age of 45 were excluded from the two aforementioned studies. However, if one takes into account the increase in the incidence of stroke with age, this is precisely the age class (45–65) that is most concerned by the issue of work re-entry after a stroke. Moreover, in a context in which the retirement age is being raised, the question of maintaining these older people in employment will arise with increasing frequency. In our study, 78% of the subjects were over the age of 45 at the time of their stroke, with the over-50s accounting for about 60% of the study population and the over-55s accounting for about 40%. Even though we were not able to detect a relationship between age and work re-entry, the low return to work rate observed in our sample doubtless reflects the specific aspects of employment in these sectors of the general population. In effect, the employment rate for the over-50s (referred to as called “seniors” in France’s jobs market) is particularly low: 52% for the 50–64 age class (and just 37% for the 55–64 class), versus 67% for the 15–49 class (2005 data from the INSEE).

The mean post-stroke time interval to a return to work found in our study (19.2 months) is longer than that observed in previous studies. In the international literature, this time interval is most often reported as being between 3 and 6 months . However, as emphasized underlined by Wozniak et al. in a literature review, the inclusion criteria and the follow-up times were highly variable. Moreover, the specific characteristics of each country’s healthcare systems and financial and social benefits make comparisons difficult. In the French study by Neau et al. , the mean time interval before returning to work was 8 months. Here again, the severity of the functional sequelae and patients’ age very probably explain the significant difference with our value. It is also important to bear in mind that in our survey, 50% of the patients who returned to work had changed work position; this often requires more time that returning to the same job as before.

Thirty-nine of our patients (67.8%) had not returned to work. Most of these people mentioned motor sequelae (76.5%) and cognitive and/or language disorders (61.8%) as the main reasons for not doing so. About one in four patients stated fatigue as a significant obstacle to the resumption of work. Fatigue is frequent in stroke victims (between 39 to 72% ) and could thus constitute an obstacle to work re-entry. According to the patients, sensory and visual impairments (present in 48.2% and 21.4% of cases, respectively) do not appear to represent a major obstacle to work re-entry. This suggests that these disorders generally have a minor impact on professional activity.

Our study’s secondary objective was to identify prognostic possible factors for the return to work after a stroke. To the best of our knowledge, none of the French studies in this field have specifically focused on prognostic factors, other than Pradat et al. who focused on prognostic neuropsychological markers . Our results must thus be compared with those in the international literature.

In our survey, the mean age of patients who had returned to work (44.8) was lower than that for patients who had not (49.9 years), however the difference was not statistically significant ( P = 0.17). Worldwide, studies tend to show that a younger age is associated with a better return to work rate , although some authors contest this . There are several arguments in support of this hypothesis : a younger age is often associated with better neurological recovery, greater ease of adaptation and greater motivation to return to work. Employers may also be more inclined to keep younger employees.

On the basis of our results, gender did not appear to influence the return to work rate. This agrees with the data from most of the previous studies in this field . However, one study reported that women may be less likely to resume work than men (odd ratio [95% confidence interval] = 0.45 [0.21–0.91]). In a recent, prospective multicentre study , male stroke victims appear to return to work earlier than women. We did not detect any relationship between returning to work and the patient’s educational level, in contrast to what has been described by other authors as a positive predictive factor . However, our study underlined the crucial role of the pre-stroke family situation in the return to work. Our results confirmed those of a previous study showing that living alone is negatively associated with a return to work . One can suppose that the support provided by a partner limits the risk of occurrence of a depressive state, which is known to be a negative predictive factor for work re-entry .

Our results agree with the literature data on the absence of a relationship between the return to work and the type and site of the stroke . In contrast, and as emphasized by several authors , we showed that the severity of functional sequelae (estimated by the Barthel index and the modified Rankin score) was negatively associated with a return to work. However, it must be stressed that the patients who did not return to work had a mean Barthel index of over 80; this means that most of these individuals had achieved a good level of independence in the basic activities of daily living. Although over 75% of our patients mentioned their motor sequelae as an obstacle to returning to work, we did not observe a statistically significant relationship between the return to work and a mention of motor disorders in the patient’s medical records. This was also the case for sensory, cognitive and visual disorders. However, these findings must be interpreted with caution because the severity and the nature of disorders had not been specified in our data collection process. In our study, only the existence of language disorders represented a statistically significant, negative predictive factor for returning to employment. Some studies have already shown that aphasic patients have more trouble returning to work than non-aphasic patients do . Of course, poorly intelligible speech compromises the resumption of professional activity. Even patients who recover well from language disorders may suffer from communication problems in some work situations (multiperson conversations, conversations with background noise, speaking in public, telephone work, etc.).

In contrast to several other reports , we did not find any relationship between the socioprofessional category and the return to work rate. However, the return to work rate was higher for “white collar” jobs (45.5%) than for “blue collar” jobs (23.5%), with a trend towards statistical significance ( P = 0.08). These results agree with other studies , although it must be borne in mind that the validity of the “white collar”/“blue collar” classification (frequently used in English-language publications) can be contested. Lastly, to the best of our knowledge, several work-related factors have not previously been studied in France: company size, time in the work position and time with the employer. In the international literature, one study did assess these work-related factors but concluded that they did not influence the likelihood of returning to work after a stroke. Our work therefore agrees with these previous findings.

The rapid implementation of a proactive approach to work re-entry appears to increase the chances of returning to work. However, it must be emphasized that the patients who did not received this professional support either had a poor state of health that clearly ruled out work or had not complied with the proposed care (although we were not able to determine the reasons for this). In our experience, some patients consider (rightly or wrongly) that a return to work will not pose any particular difficulties and so assistance with work re-entry is not necessary. In some cases, it may be that the patient does not wish to return to work because of a depressive state or because he/she considered that the previous working conditions were too unfavourable to envisage re-entry.

There had been contact between the occupational physician and the CPRM staff for about 60% of patients who had resumed work. Half of the latter had consulted their occupational physician before a prospective return to work (pre-return consultation). Our study’s methodology prevented us from precisely determining the occupational physician’s impact on work re-entry, since it is probable that he/she was tended to be contacted once a return to work seemed possible. Nevertheless, the occupational physician obviously has a primordial role to play in work re-entry after stroke. He/she is an essential link between the salaried employee and the employer and can suggest workplace adaptations or limitations to reconcile the patient’s disability and its professional activity. The occupational physician should thus be involved early in the work re-entry process and the collaboration between the CPRM and occupational medicine services merits further reinforcement. Several approaches could be envisaged: telephone discussion, transmission of consultation or hospitalization reports, personalized letters for the occupational physician and multidisciplinary consultations involving CPRM physicians, occupational physician, social workers, etc. However, this collaboration can only be envisaged if it maintains patient-physician confidentiality. In France, medical information can only be sent to the occupational physician with the salaried employee’s consent. Furthermore, an occupational physician can be confronted with the reality of corporate life because even though he/she has an advisory role for the employee and the employer, this latter makes the final decision concerning employment. We also suggest that stroke victims considering a return to work should consult their occupational physician with a view to planning and facilitating the implementation of necessary measures for work re-entry. However, this pre-return consultation can only be requested by the salaried employee, the family doctor or the social security physician (Article R4624-23 of the French Labour Code). We believe that it is also important to incite the patients to request RQTH status, which gives them access to a set of measures for promote job re-entry or maintenance (training, skills reviews, workplace adaptations, etc.). This accreditation also falls within the French legal framework requiring employers to employ a percentage of handicapped workers.

Lastly, our survey suggests that there is a close relationship between the return to work and the resumption of motor vehicle driving after a stroke. To the best of our knowledge, researchers have not previously looked at this potential link, even though driving is (along with employment) a critical factor in social reintegration. We found that 83% of the patients who had returned to work had also resumed driving and that there was a clear correlation between the post-stroke time interval to resumption of driving (which usually occurred first) and the time to return to work.

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, our study population was relatively small – notably because this was a single-centre study. The absence of a significant relationship between the return to work and certain factors studied here (such as age, educational level and “white collar” vs. “blue collar” jobs) may be due (at least in part) to a lack of statistical power. It must nevertheless be borne in mind that over 75% of our patients replied to the questionnaire, suggesting that our sample reflects the target population quite well. This response rate is especially satisfactory because we surveyed patients at least 3 years after stroke and few were lost to follow-up. Our study probably also featured a degree of reporting bias. In fact, some of the respondees presented present cognitive sequelae of their stroke, such as anosognosia. Some questionnaires were filled out by a carer or family member when the patient was unable to do so him/herself. Furthermore, we did not specifically investigate a number of factors reported by certain authors as being negatively associated with a return to work. This was the case for the initial severity of the stroke , which was generally not specified in our patients’ medical records. This was also the case for psychiatric disorders in general and post-stroke depression in particular . However, it would have been difficult to collect this type of data in a questionnaire that we wanted to be easy for the patients to fill out.

1.5

Conclusion

The return to work after stroke has an essential role in the patient’s social reintegration. Despite post-stroke impairments, a return to work is possible – even when the initial impact is severe enough to necessitate care in a CPRM. The patients often took a long time to return to work (between 1 and 2 years). A prospective, multicentre study would enable better evaluation of the influence of sociodemographic, medical and socioprofessional factors on the return to work after a stroke. Support for work re-entry by these patients should be part of an approach involving early, close collaboration between occupational medicine services and CPRMs.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

Valérie Fazillot, Samuel Libgot and Françoise Sere.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) est un problème majeur de santé publique en France et dans le monde. Les conséquences neurologiques et fonctionnelles peuvent être sévères et l’AVC constitue actuellement la première cause de handicap acquis chez l’adulte en France. L’AVC a un coût socio-économique très élevé. Il occasionne des coûts directs liés aux soins (hospitalisation, traitements, rééducation) et des coûts indirects liés à la baisse de productivité, c’est-à-dire aux répercussions que peuvent avoir les séquelles sur la capacité de travail. En effet, bien que l’incidence de l’AVC augmente avec l’âge, cette pathologie concerne également le sujet jeune en âge de travailler, puisque environ un quart des victimes ont moins de 65 ans (soit 32 500 cas/an) et environ 15 % des patients ont moins de 55 ans (soit 19 500 cas/an) . La question du devenir professionnel de ces patients va donc se poser précocement et aux différentes étapes de la rééducation et de la réadaptation.

Dans la littérature, plusieurs travaux ont été consacrés à la reprise du travail après un AVC ( Tableau 1 ). Selon ces publications, les taux de reprise du travail fluctuent entre 14 et 73 % et les délais de reprise du travail après AVC sont très variables d’une étude à l’autre. Les rares études françaises ont montré des taux de reprise du travail entre 59 et 73 % . La comparaison de toutes ces études est cependant difficile pour diverses raisons. D’une part, il existe une grande hétérogénéité méthodologique : caractéristiques des populations étudiées (âge, type d’AVC), mode de recrutement des patients et durée de suivi sont très variables. D’autre part, la réinsertion professionnelle dépend des particularités sociales, culturelles, du système de santé et des mesures d’accompagnement spécifiques de chaque pays.

| Année de publication | Auteur [référence] | Pays | Taille de l’échantillon | Pourcentage de reprise du travail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Kotila | Finlande | 58 | 55 |

| 1985 | Howard | États-Unis | 379 | 19 |

| 1990 | Black-Schaffer | États-Unis | 79 | 49 |

| 1991 | Bergmann | Allemagne | 204 | 14 |

| 1993 | Saeki | Japon | 230 | 58 |

| 1994 | Ferro | Portugal | 184 | 73 |

| 1997 | Hsieh | Taïwan | 248 | 58 |

| 1997 | Pradat-Diehl | France | 22 | 59 |

| 1998 | Neau | France | 63 | 73 |

| 1999 | Wozniak | États-Unis | 156 | 51 |

| 2000 | Teasell | Canada | 64 | 20 |

| 2002 | Leys | France | 265 | 65 |

| 2003 | Vestling | Suède | 120 | 41 |

| 2004 | Varona | Espagne | 240 | 53 |

| 2008 | Glozier | Nouvelle-Zélande | 210 | 53 |

| 2009 | Busch | Angleterre | 266 | 35 |

| 2009 | Gabriele | Allemagne | 60 | 27 |

| 2010 | Saeki | Japon | 253 | 55 |

| 2011 | Tanaka | Japon | 335 | 30 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree