Replacement Arthroplasty in Osteoarthritis

Charlotte Shum

Andrew Weiland

INTRODUCTION

Primary osteoarthritis (OA) of the elbow is an uncommon condition whose treatment only recently has begun to be addressed in peer-reviewed journals and standardized medical textbooks. Primary OA of the elbow was recognized as a disease in miners in Great Britain by Lawrence in 1955 (1), whereas age-related changes in the articular surface of the distal humerus and the radiohumeral joint had been described by Ortner in 1968 (2) and by Goodfellow and Bullough in 1967 (3). Detailed clinical and radiographic descriptions and recommended treatment options for primary elbow OA were not described until the 1970s when studies by Minami (4) and Kashiwagi were published in Japan (5). Increased awareness of primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow by the orthopedic community of late is reflected in our current medical literature, and with the knowledge available today we are able to delineate a treatment algorithm to address the different aspects of this disease entity. The role of total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) is, however, at present limited and would benefit from further study because there are no prospective studies and only one published retrospective case (series) study evaluating TEA in this patient population (6). This chapter will provide an overview of primary OA of the elbow including its clinical presentation, evaluation, and treatment options with focus on TEA.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

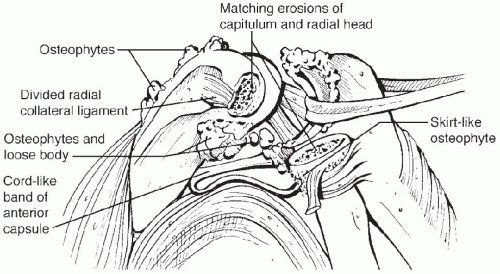

There are characteristic pathologic changes that occur within the elbow joint as primary OA develops (4,7,8) (Fig. 24-1). Osteophyte formation arises in the olecranon, olecranon fossa, coronoid, and coronoid fossa amid (despite) initial maintenance of the joint space. Ensuing changes include formation of osteophytes at the radial

head margin and of loose bodies. Bone loss is less of a concern with primary elbow OA; the periarticular bone is typically very hard, and heterotopic bone may also result postoperatively as a consequence of the hypertrophic nature of the disease. In the early stages the radiohumeral is less acutely involved.

head margin and of loose bodies. Bone loss is less of a concern with primary elbow OA; the periarticular bone is typically very hard, and heterotopic bone may also result postoperatively as a consequence of the hypertrophic nature of the disease. In the early stages the radiohumeral is less acutely involved.

O’Driscoll reported that in the advanced stages of primary elbow OA, the radioulnar joint can become afflicted and lastly the radiohumeral joint may become involved (9). Other reports have noted that in its advanced stages, degenerative changes in the radiohumeral joint may be more severe than those in the ulnohumeral joint (10). Tsuge and Mizuseki wrote of an “erosion angle” (42 to 53 degrees, average 48 degrees) between the long axis of the humerus and the capitellar surface on a lateral radiograph or tomogram, which reflects the articular cartilage loss between radius and capitellum with the capitellum appearing to have been shaved obliquely (10). They posited that the radiohumeral joint was “most vulnerable to axial, rotational, and possibly shearing stresses at 45 to 50 degrees of flexion” and that the resultant (articular cartilage) destruction brought about fragment formation, which initiated fibrosis and loose body formation.

In addition to bony changes within the elbow joint, soft-tissue changes occur as well. Capsular contracture is a component of loss of motion. Fibrosis of the anterior capsule contributes to loss of extension. Collateral ligaments often remain intact and may ossify as part of the hypertrophic process; they may need to be partially excised during treatment (e.g., posterior portion of ulnar collateral ligament) to improve range of motion (8).

Degenerative elbows in athletes frequently will comprise a spectrum of pathologic changes including loose bodies and bone spurs. In our experience valgus hyperextension overload in the throwing athlete can lead to valgus laxity with attenuation of the medial collateral ligament (MCL); this can result in development of posteromedial impingement/fragmentation with spur formation and fragmentation of the posteromedial olecranon and humerus, loose body formation, and capsular synovial thickening. Degenerative arthritis can eventually ensue.

Incidence and Pathophysiology

Symptomatic OA of the elbow has been found to affect approximately 2% of the population, and afflicted patients represent 1% to 2% of all patients diagnosed with degenerative arthritis of the body. This is a condition of men and is seen rarely in women; males predominate women in occurrence in ratios of 4 or 5 to 1 (8). The disease has rarely been found in patients younger than age 40 years; average age of presentation is about 50 years, although reported ages have ranged from 20 years to 65 years. Of patients 80% to 90% experience symptoms in their dominant extremity, although between 25% and 60% of patients note bilateral involvement (6). The exact etiology of primary degenerative elbow arthritis is still unknown. It is generally attributed to overuse because it is more commonly seen in workers who perform heavy manual labor. About 60% of patients report employment or hobbies requiring repetitive use of the limb (6). The few younger patients who present with this disease likely have a predisposing condition such as osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) (11). Sports including throwing activities have been found to predispose to elbow disorders including “little-league elbow;” OCD; posteromedial impingement; and, in the long term, possibly degenerative arthritis. Boxing also has been noted to result in elbow OA characterized by formation of multiple loose bodies. Moreover, the infrequency of primary degenerative elbow arthritis has led physicians to neglect this disease and to misinterpret it as a posttraumatic condition.

In the early stages of the disease patients frequently will experience loss of full extension with flexion contracture of about 30 degrees; this is most commonly their reason for seeking medical attention. Elbow stiffness is also a common presenting symptom, and some patients also will encounter mild to moderate pain. Initially the pain is the

result of mechanical impingement at extreme ranges of motion. Pain more frequently occurs during terminal extension, although about 50% also have pain during terminal flexion. As the severity of the arthritis progresses, the pain may occur throughout the arc of motion. The radiohumeral joint is usually unaffected in the early stages, and patients do not notice difficulties with forearm rotation. About 10% of patients will present for evaluation of elbow catching or locking as a result of loose body formation, which occurs in approximately 20% of degenerative elbows (9). Approximately 10% to 20% of patients also will have symptoms consistent with ulnar nerve irritation as a result of the hypertrophic changes and/or ganglia along the medial aspect of the ulnohumeral articulation (12).

result of mechanical impingement at extreme ranges of motion. Pain more frequently occurs during terminal extension, although about 50% also have pain during terminal flexion. As the severity of the arthritis progresses, the pain may occur throughout the arc of motion. The radiohumeral joint is usually unaffected in the early stages, and patients do not notice difficulties with forearm rotation. About 10% of patients will present for evaluation of elbow catching or locking as a result of loose body formation, which occurs in approximately 20% of degenerative elbows (9). Approximately 10% to 20% of patients also will have symptoms consistent with ulnar nerve irritation as a result of the hypertrophic changes and/or ganglia along the medial aspect of the ulnohumeral articulation (12).

EVALUATION

The typical patient with primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow is a man older than 40 years of age. He will likely be employed in a job requiring repetitive heavy use of the arm (13). Younger patients also may provide histories of intensive athletic endeavors including weightlifting, baseball and other throwing activities, and boxing. Throwing athletes may note early pain and stiffness that loosens up and eases after a warm-up period of throwing. Morrey has noted elbow OA in patients who require regular use of such assistive devices as crutches or wheelchairs (6).

Although patients may complain of several problems, there are four predominant symptoms that vary depending on the degree of involvement: loss of motion, catching, terminal pain, and ulnar nerve symptoms. Loss of motion with complaint of flexion contracture is the most common presenting symptom. Patients usually present for evaluation of the elbow when their range of motion becomes functionally limited. Loss of extension is often partially the result of posterior olecranon and humeral osteophytes. Loss of flexion is frequently secondary to (in part the result of) anterior osteophytes on the coronoid or its fossa as well as loose bodies. Pain may be experienced at the end ranges of motion as a result of mechanical impingement that commonly affects extension more than flexion. They may feel pain while carrying objects with the elbow in extension. Rest pain or pain during the arc of motion is uncommon and does not occur until more severe stages. Catching or locking may occur as a result of loose bodies within the joint. Irritation of the ulnar nerve at the elbow with resultant symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome may also be present in up to 20% of patients.

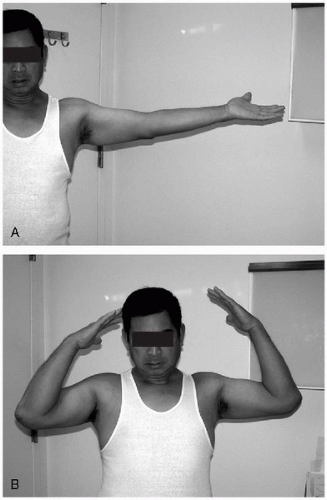

Physical examination will correspond to the patients’ complaints. Range of motion in the extension-flexion arc will average approximately 30 to 120 degrees (Fig. 24-2). Crepitus may be present with range of motion. Supinationpronation is largely unaffected until later stages. Ulnar nerve symptoms such as decreased sensation and weakness in the ulnar nerve distribution, positive Tinel’s sign at the elbow, and positive sustained elbow flexion test may also be present. Because this is a disease of repetitive and/or cumulative use, ligaments frequently remain intact, and gross instability is not a characteristic finding. Patients who were once throwing athletes may have valgus laxity with attenuation of the MCL; physical examination findings in the early stages might include posteromedial tenderness with the valgus hyperextension test. The anterior bundle of the ulnar collateral ligament can be isolated with valgus stress testing at 90 degrees flexion in pronation (14).

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

In addition to a pertinent history and physical examination findings, further workup is straightforward and involves imaging studies. Routine anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are diagnostic and illustrate classic aspects

of the disease. The anteroposterior view will show ossification and osteophyte formation of the olecranon and coronoid fossa (Fig. 24-3). The lateral view will show an anterior osteophyte of the coronoid and a posterior osteophyte of the olecranon tip. Loose bodies are present in 20% to 50% and can be seen anteriorly and/or posteriorly. Radiohumeral involvement is observed in 25% to 50%; both radioulnar and radiohumeral joints may be affected in later stages of the disease. A cubital tunnel view can be obtained if there is ulnar nerve irritation (4,6,7).

of the disease. The anteroposterior view will show ossification and osteophyte formation of the olecranon and coronoid fossa (Fig. 24-3). The lateral view will show an anterior osteophyte of the coronoid and a posterior osteophyte of the olecranon tip. Loose bodies are present in 20% to 50% and can be seen anteriorly and/or posteriorly. Radiohumeral involvement is observed in 25% to 50%; both radioulnar and radiohumeral joints may be affected in later stages of the disease. A cubital tunnel view can be obtained if there is ulnar nerve irritation (4,6,7).

Although plain films are usually sufficient for diagnosis and planning of treatment, computed tomography scan may be ordered in earlier stages. The study can be helpful in better characterizing osteophyte formation on the humerus and ulna and in revealing existence and location of loose bodies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree