One of the more challenging aspects beyond acute concussion management occurs when symptoms do not resolve as anticipated over time. The term postconcussion syndrome generally refers to a presentation of multiple ongoing symptoms months to years from injury, typically comprised of physical, cognitive, and emotional complaints such as headaches, poor sleep, poor concentration, dizziness, and irritability. Although individual factors vary, the condition is often regarded as multifactorial. Persistent issues can pose a threat to full community reintegration following concussion and reduce overall quality of life; thus early recognition and treatment are essential to optimize long-term outcomes.

Key points

- •

Early education about potential symptoms and expected recovery patterns is a mainstay of prevention.

- •

Headaches are the most common physical symptom and most common persisting symptom after mild traumatic brain injury.

- •

Clinical presentation is multifactorial and may be resistant to routine approaches, necessitating an individualized plan of care.

- •

A symptom-based approach with particular attention to sleep regulation is recommended.

- •

Utilize regular follow-up with realistic and measurable patient-centered goals.

Introduction

One of the more challenging aspects beyond acute concussion management occurs when symptoms do not resolve as anticipated over time, which may occur in upwards of 15% of all mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) patients. The term postconcussion syndrome generally refers to a presentation of multiple ongoing symptoms months to years from injury, typically comprised of physical, cognitive, and emotional complaints such as headaches, poor sleep, poor concentration, dizziness, and irritability.

Notably, these symptoms are common in the general healthy population and not necessarily specific to mTBI. Although individual factors vary, the condition is often regarded as multifactorial including biological, psychological, and social factors. Persistent issues can pose a threat to full community reintegration following concussion and reduce overall quality of life; thus early recognition and treatment are essential to optimize long term outcomes.

Introduction

One of the more challenging aspects beyond acute concussion management occurs when symptoms do not resolve as anticipated over time, which may occur in upwards of 15% of all mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) patients. The term postconcussion syndrome generally refers to a presentation of multiple ongoing symptoms months to years from injury, typically comprised of physical, cognitive, and emotional complaints such as headaches, poor sleep, poor concentration, dizziness, and irritability.

Notably, these symptoms are common in the general healthy population and not necessarily specific to mTBI. Although individual factors vary, the condition is often regarded as multifactorial including biological, psychological, and social factors. Persistent issues can pose a threat to full community reintegration following concussion and reduce overall quality of life; thus early recognition and treatment are essential to optimize long term outcomes.

General approach

Prevention

The mainstay of prevention of chronic symptoms following concussion is early education focused on expectations of recovery and symptom management. Patients should be advised that most will experience a full recovery of symptoms. An individualized plan for gradual return to activity with guidance about avoidance of symptom exacerbation is an effective step that can be implemented during initial concussion management.

Identification

Issues with ongoing symptoms are usually identified in a scheduled follow-up visit or through patient request for reassessment. Full history and physical examination are warranted to assess possible contributors to symptom presentation.

There are multiple tools that may be utilized to track postconcussion symptoms ( Box 1 ).

Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory

Postconcussion Syndrome Checklist

Concussion Symptom Checklist

Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire

Early Intervention

Education about coping strategies and expectation of recovery at time of injury has been associated with less stress and fewer symptoms at 3 months after injury. This can begin at the time of initial concussion evaluation, and accomplished through conversation, handouts, or referral to online sources such as Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center.

Communication

Current verbiage regarding the event (eg, mild traumatic brain injury [mTBI], concussion, brain damage) can be confusing for both patients and providers, potentially increasing the perception that these injuries are associated with ongoing disability. It is important to frame the conversation in terms of multiple contributing factors, many of which are modifiable, with positive expectations of recovery. Validating patient distress and subjective experience is important and does not have to be immediately coupled with attribution to brain dysfunction or damage. Important points include

- •

Consider concussion as a descriptor of the event versus mTBI

- •

Build an early and strong alliance with patient through active listening

- •

Design symptom-based treatment plan focused on patient-centered priorities

- •

Structured follow-up with realistic and measurable goals

Conceptualizing Cocontributing Factors

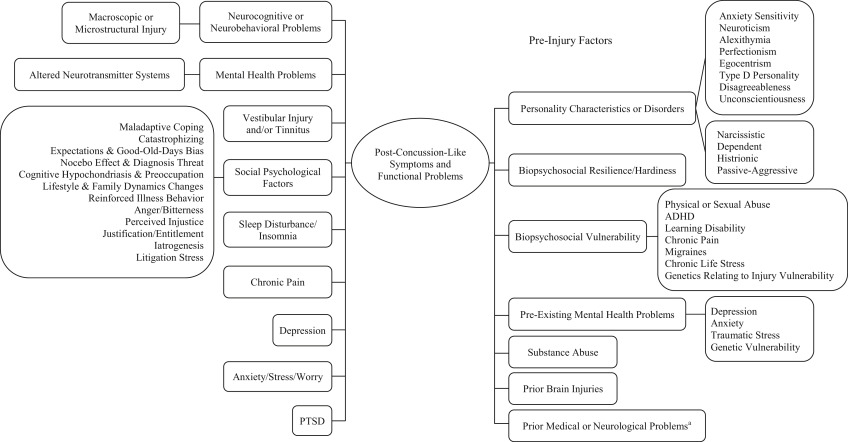

It is well established that symptoms persisting after concussion are multifactorial, including factors such as genetics, personality, mental health disorders, and psychosocial stressors. Premorbid history of anxiety is particularly predictive of development of postconcussive symptoms. A full psycho-social assessment will help uncover conditions that may be contributing to ongoing symptoms and possibly interfering with recovery. Fig. 1 displays a biopsychosocial conceptualization of poor outcomes after mTBI.

Caveats for Pharmacologic Treatment Options

Symptom-based interventions often include pharmacologic options. Given that persistent symptoms often occur as a group (sleep plus mood plus concentration problems), use of pharmacotherapies may quickly produce a new condition of polypharmacy; thus careful consideration of each symptom and a comprehensive approach will help dictate the medication component of any treatment plan. Particular concerns include

- •

Be aware that many central nervous system (CNS)-acting medications have adverse effects that mimic other postconcussion symptoms (such as tricyclic antidepressants used for insomnia possibly worsening the dizziness symptom).

- •

Consider prioritizing the symptom that is most bothersome or most contributory to the overall presentation, such as insomnia.

- •

Educate the patient as to risks and benefits, including how this may impact (better or worse) other co-occurring symptoms.

- •

Estimate duration of pharmacotherapy and discuss with patient. Most of these medications are meant for temporary symptom reduction and not intended for life-long use.

- •

Ensure that the trial includes upward titration (as tolerated) to minimally effective dosing for the recommended minimum treatment duration prior to considering treatment failure. Premature assessment of any intervention as ineffective may reduce overall options in an already difficult and often refractory symptom complex.

- •

Track measurable and meaningful goals for each medication, weighing efficacy versus risk during the follow-up discussions. There are multiple widely available free applications for symptom tracking such as the Concussion Coach Mobile App.

- •

Special considerations

- ○

Seizures: many medications will lower the seizure threshold

- ○

Cardiac history: some have potential for cardiac adverse effects, such as stimulants and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- ○

Substance abuse: general caution with the use of medication in patients with ongoing substance abuse, particularly use of alcohol, amphetamines and benzodiazapines

- ○

Avoid long-term use of opioid medications

- ○

Nonpharmacological Approach

Individual symptoms can be targeted with a variety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacological approaches, but it is important to understand the overarching themes of successful rehabilitation for persistent symptoms after mTBI ( Box 2 ).

Education about mild traumatic brain injury, including natural course of recovery

Reassurance of positive outcomes

Avoidance of hazardous behaviors during acute recovery

Gradual return to activity and life roles as symptoms improve

Careful monitoring and early intervention for adverse emotional response

Symptom specific treatment

Ready access to providers during acute and subacute recovery periods

Rest versus return to activity

There is a fine balance between activity and rest following mTBI. Too much activity too soon or prolonged activity restriction may both have negative consequences during the recovery period. An individualized plan for gradual return to activity guided by symptom resolution is recommended to promote optimal function :

- •

One to two days of rest following acute mTBI was recommended by the 2012 Zurich Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport.

- •

Excessive, early cognitive activity may prolong recovery from concussion.

- •

Bedrest has not proven to be an effective strategy following mTBI.

For chronic or persistent symptoms, engagement with regular aerobic exercise that does not cause symptom exacerbation is regarded as an effective method for reducing postconcussion symptoms and improving activity tolerance.

Symptom-specific rehabilitation interventions

Headaches

Considerations

- •

Headaches are the most common physical symptom reported after mTBI, and the most common persisting symptoms, with prevalence rates over 90% in concussed athletes.

- •

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition-beta (ICHD- III) defines post-traumatic headaches (PTH) as a secondary headache disorder attributed to head and/or neck trauma in close temporal relationship to the traumatic event (ie, within 7 days of injury to the head or within 7 days of regaining consciousness after injury or of discontinuation of any medication that could impair perception or experience of the headache).

- •

PTH symptoms can present similarly to primary headache conditions like migraine or tension-type headache, but the onset or exacerbation of the headache symptoms must be secondary to trauma exposure.

- •

PTH is identified as either acute or chronic based on the duration and persistence of the post-traumatic headaches ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Acute versus chronic post-traumatic headache

Acute Post-traumatic headache

Headache resolves within 3 mo or trauma exposure was <3 mo ago

Chronic post-traumatic headache

Headache persists beyond 3 mo

- •

Most patients with PTH recover within 1 to 2 weeks of injury, but PTH can last for years. Chronic PTH is associated with decreased quality of life, impaired activities of daily living, loss of work, and impaired societal functioning.

- •

Begin with a focused headache history and full physical examination to identify the headache subtypes and to rule out other serious intracranial pathology, which may require emergent management.

Management

The management of PTH is empiric and is based on the primary headache phenotypes, which include migraine, tension-type, cervicogenic, neuralgic, or mixed headaches. The initial management should provide education on the headache type and simple lifestyle modifications (eg, improve sleep hygiene, regular meals, improved hydration, minimizing stress, identification and avoidance of triggers, and exercise) to help mitigate reoccurrence of headaches.

Nonpharmacological management of PTH may include use of

- •

Physical therapy

- •

Biofeedback

- •

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- •

Acupuncture

- •

Hot/cold packs

- •

Cranial analgesic electrotherapeutic devices

- •

Massage therapy

- •

Relaxation training

Pharmacologic management of PTH includes both medication and interventional procedures to help alleviate headaches symptoms. Clinicians should also be aware of medication overuse headaches (MOH), which may result from the use of analgesics, opioids, ergot alkaloids, and triptans, which can be used for the treatment of PTH. The treatment of MOH includes removal of the offending agents and subsequent treatment of the primary headache disorder.

Pharmacologic management for PTH can be divided in abortive and prophylactic management ( Table 2 ).