Chronic graft-versus-host disease is a potentially debilitating complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Due to the direct inflammatory effects of the disease on tissue, and the impact on muscle and bone of the high-dose glucocorticoid immunosuppression used to treat the disease, patients are at risk of developing multifactorial functional impairment. This review outlines the clinical assessment and rehabilitation interventions to manage aspects of the disease that cause the most impairment: involvement of the skin/fascial and cardiopulmonary organ systems, as well as steroid-induced myopathy and bone and joint destruction.

Key points

- •

Both the direct inflammatory effects of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and the treatment to suppress the disease can significantly impact function and cause pain.

- •

Few studies exist to guide management; the authors review the extant literature and discuss approaches that show promise based on their clinical experience.

- •

GVHD can affect many organ systems; this review addresses the skin/fascia and cardiac/pulmonary systems because these likely are associated with the highest degree of impairment.

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is the most common and potentially devastating complication of allogeneic (donor) hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), often referred to as bone marrow transplantation. cGVHD occurs in 30% to 70% of patients who receive an HSCT for hematologic malignancy, and is caused by the newly donated T cells attacking highly mitotic areas of the transplant recipient’s body that are considered foreign to the engrafted immune cells. Most affected by cGVHD are the skin and fascia, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, hepatic, ocular, and oral mucosal organ systems. This inflammatory process can cause significant damage to the tissues affected, directly contributing to functional impairment. The treatment of cGVHD, which typically involves high-dose corticosteroids to suppress the immune system as first-line therapy, also can be destructive and necessitate rehabilitation to restore function and quality of life.

Although the HSCT itself requires special considerations in rehabilitation, recently transplanted patients are often pancytopenic and at increased risk for infection and bleeding events, this article addresses the rehabilitation of specific impairments directly or indirectly caused by cGVHD. Furthermore, autologous HSCT, in which a person’s own immune system is retransplanted into their body after myeloablation, is not discussed, as this does not cause cGVHD. Finally, acute GVHD represents a pathologically distinct process, typically occurring within the first 100 days after transplantation and affects the dermal and gastrointestinal systems, and does not impact function in the same way as cGVHD. This is not directly discussed, although glucocorticoids are first-line treatment of acute GVHD, of which the side effects are addressed.

For purposes of simplicity, we have broken down this review into categories of the most physically devastating manifestations in these patients: skin/fascial and cardiopulmonary cGVHD, and the effects of steroids on muscle and bone. Manifestations of cGVHD in other organ systems, is beyond the scope of this review but a brief summary is listed in Table 1 . For further information on the sequelae and symptomatic treatment of cGVHD beyond the measures discussed herein, the Ancillary and Supportive Care Working Group Report from the 2015 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project for cGVHD is recommended reading.

| Organ System | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Skin (dermal) | Erythematous maculopapular rash, pain, desquamation |

| Skin (fascial) | Contracture, edema |

| Gastrointestinal | Painful cramping, watery stool |

| Oral | Painful lichenoid lesions, dryness, thrush, odynophagia, dysphagia |

| Ocular | Dryness, conjunctivitis |

| Vulvovaginal | Dryness, sclerosis, dyspareunia |

| Pulmonary | Bronchiolitis obliterans, airflow obstruction |

| Neurologic | Myasthenia gravis (rare), polymyositis (rare), Zoster |

Introduction

Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is the most common and potentially devastating complication of allogeneic (donor) hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), often referred to as bone marrow transplantation. cGVHD occurs in 30% to 70% of patients who receive an HSCT for hematologic malignancy, and is caused by the newly donated T cells attacking highly mitotic areas of the transplant recipient’s body that are considered foreign to the engrafted immune cells. Most affected by cGVHD are the skin and fascia, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, hepatic, ocular, and oral mucosal organ systems. This inflammatory process can cause significant damage to the tissues affected, directly contributing to functional impairment. The treatment of cGVHD, which typically involves high-dose corticosteroids to suppress the immune system as first-line therapy, also can be destructive and necessitate rehabilitation to restore function and quality of life.

Although the HSCT itself requires special considerations in rehabilitation, recently transplanted patients are often pancytopenic and at increased risk for infection and bleeding events, this article addresses the rehabilitation of specific impairments directly or indirectly caused by cGVHD. Furthermore, autologous HSCT, in which a person’s own immune system is retransplanted into their body after myeloablation, is not discussed, as this does not cause cGVHD. Finally, acute GVHD represents a pathologically distinct process, typically occurring within the first 100 days after transplantation and affects the dermal and gastrointestinal systems, and does not impact function in the same way as cGVHD. This is not directly discussed, although glucocorticoids are first-line treatment of acute GVHD, of which the side effects are addressed.

For purposes of simplicity, we have broken down this review into categories of the most physically devastating manifestations in these patients: skin/fascial and cardiopulmonary cGVHD, and the effects of steroids on muscle and bone. Manifestations of cGVHD in other organ systems, is beyond the scope of this review but a brief summary is listed in Table 1 . For further information on the sequelae and symptomatic treatment of cGVHD beyond the measures discussed herein, the Ancillary and Supportive Care Working Group Report from the 2015 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project for cGVHD is recommended reading.

| Organ System | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Skin (dermal) | Erythematous maculopapular rash, pain, desquamation |

| Skin (fascial) | Contracture, edema |

| Gastrointestinal | Painful cramping, watery stool |

| Oral | Painful lichenoid lesions, dryness, thrush, odynophagia, dysphagia |

| Ocular | Dryness, conjunctivitis |

| Vulvovaginal | Dryness, sclerosis, dyspareunia |

| Pulmonary | Bronchiolitis obliterans, airflow obstruction |

| Neurologic | Myasthenia gravis (rare), polymyositis (rare), Zoster |

Skin and fascial chronic graft-versus-host disease

Cutaneous cGVHD is the most common manifestation of the disease, nearly 100% of people with cGVHD will develop this, and can affect one or both of the dermis and fascia. Dermal involvement typically results in a maculopapular lichenoid rash and itself does not cause direct physical impairment; however, it is often the first sign of a cGVHD flare, and may indicate that corticosteroids will soon be initiated or the dose increased.

Fascial cGVHD, on the other hand, is similar to eosinophilic fasciitis and can cause edema, fibrosis, and joint contracture. Edema is often the first sign of fascial involvement, and the most common joints affected are the wrists, shoulders, and ankles, with distal joints affected first in a symmetric, bilateral fashion. In addition to contracture, patients may develop joint destruction and skin breakdown as the upper layers of the skin become thin from the disease and corticosteroid use, and the deeper layers thicken.

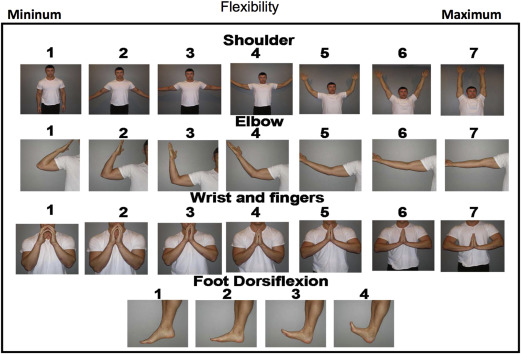

When examining a patient, the progression of skin sclerosis from “moveable,” that is, being able to easily compress focal areas of sclerosis, to “nonmoveable,” in which there is diffuse thickening that is not compressible, is a physical examination finding suggestive of chronic, difficult-to-reverse fibrosis. Sonographic measures of elasticity show promise in fibrosis assessment, although no large trials have been conducted to validate this modality. Physical examination also should assess range of motion, particularly with the photographic range of motion (P-ROM) scale. This rapid, easy-to-use assessment of active range of motion at multiple joints, which can both grade the severity of involvement and monitor response to treatment, should be incorporated into the clinical assessment of all patients with fascial cGVHD ( Fig. 1 ).

Treatment for fascial cGVHD is not well understood: it is difficult to conduct large trials on such a specific manifestation of a rare disease, and most research understandably is directed at preventing and treating cGVHD, not the physical manifestations. Nevertheless, there are case series suggesting improvement in range of motion with splinting and stretching, although it is unclear if the effects were sustained. Surgical release of contractures does not work and may make restrictions worse.

In the authors’ experience, interventions also must address the underlying edema and fibrosis. Occupational therapy directed at decongestive therapy, as well as compressive garments, should be a mainstay of treatment and initiated when swelling is first detected. As a corollary, it has been shown that burn patients have a lower risk of hypertrophic scarring when wearing compression garments, likely by decreasing stagnant inflammatory fluid surrounding the fascia and interstitium. Modalities, such as paraffin baths and phonophoresis with dexamethasone, have not been studied in this population, but improve symptoms in patients with scleroderma and fasciitis, respectively, and should be considered. Iontophoresis is less likely to be helpful due to fibrosis impairing transit of medication, and friable skin making it difficult for the dermal patch to adhere ( Fig. 2 ).