Regional Disorders of the Axial Skeleton

The axial syndromes comprise the majority of the regional musculoskeletal illnesses for which medical care is sought. Back pain remains one of the most frequent presenting complaints in primary care settings.1 Neck pain is also highly prevalent. To provide a comprehensive treatment of morbidity of this magnitude, this chapter is divided into eight sections:

Differential diagnosis: recognizing systemic backache

Regional low back pain without radiculopathy

Chronicity and intermittency

Neck pain

Radiculopathies

Lumbar spinal stenosis

Insufficiency fractures

Myelopathy

The Adult Spine2 is a comprehensive treatise on axial disorders that I co-edited. The reader is encouraged to turn to that resource for expanded discussions of many of the topics I will cover in this chapter, particularly for detailed discussions of surgical considerations that are not covered here. This chapter is written from the perspective of the physician faced with a patient with a regional illness of the axial skeleton.

The diagnosis of a regional musculoskeletal illness of the axial skeleton is a diagnosis of exclusion. As discussed in Chapter 5, a “diagnosis of exclusion” is an admission of uncertainty. Furthermore, because the diagnosis is entirely based on symptoms, the level of uncertainty about pathogenesis has not abated in the centuries since Sydenham pointed the way. The advance is that we have culled from this illness a number of disease entities that, by definition, have more certain causes. The need to “exclude” such diseases from this category of illness is intellectually compelling but not necessarily good sense or good medicine. Because regional illnesses are so prevalent and systemic diseases that present with axial pain are so rare, the exercise of exclusion seldom produces a specific diagnosis, let alone a diagnosis that alters therapy or even prognosis. Therefore, considerations that derive from the differential diagnosis of regional disorders should be pursued with zeal only in a special setting. For example, in the later decades of life, the yield increases and so should the index of suspicion of the diagnostician. In the case of a working-age patient with an axial predicament, regional musculoskeletal illness is so likely the diagnosis that it behooves the physician to avoid unfounded inferences, unnecessary

testing with uninterpretable results, and ill-conceived therapies, all of which confound the acute illness and increase the likelihood that it will become chronic.

testing with uninterpretable results, and ill-conceived therapies, all of which confound the acute illness and increase the likelihood that it will become chronic.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: RECOGNIZING SYSTEMIC BACKACHE

Infections and Neoplasia

Nonetheless, there are several “red flags” in the history that should alert and impel the diagnostician. Almost all axial regional musculoskeletal illnesses force the patient to seek a static posture that unloads the involved region. Recumbency, erect seating, and static standing postures are sought. Beware of any patient whose musculoskeletal illness causes motion. Axial pain with movement, even writhing, characterizes vascular catastrophes such as aortic dissection, visceral diseases involving the retroperitoneum, obstructive uropathies, and so forth. Bone pain from metastatic infection or neoplasia characteristically is accentuated at night and causes one to pace and fidget. Most but not all of these patients have systemic symptoms such as fever or weight loss. Most, but not all, have elevated sedimentation rates if not anemia and other laboratory abnormalities associated with the particular process.3 Metastatic infections tend to localize to the disc or the epidural space; the illness is subacute and, in the latter case (which is a surgical emergency), often characterized by localizing radicular signs. Of the metastatic infections, special mention of Pott’s disease is appropriate given the resurgence of tuberculosis in rural and ghetto America and in association with HIV infection. The tubercle bacillus has a propensity to seed the anterior disc where it establishes a chronic, destructive infected granuloma that can expand across the space into the adjacent bodies. The process can dissect anteriorly into the soft tissues, including tracking along tissue planes as in a psoas abscess. The presentation is of smoldering backache prominent at rest and at night. Fever and active infection elsewhere (including intrathoracic) are inconstant features; weight loss and a positive skin test are more reliable.

Metastatic tumors can compromise spine stability or encroach on roots or structures within the canal; both are indications for emergency radiation therapy or, because of increasing success, surgical extirpation and stabilization. There are also primary neoplasms of the osseous canal. These include several benign neoplasms that occur generally in younger patients: eosinophilic granuloma, hemangiomas, aneurysmal bone cysts, osteoid osteoma, and mesenchymal tumors such as osteochondromas and chondromyxoid fibromas. Primary malignant neoplasms of the osseous canal span the entire age range: osteogenic sarcomas, chondrosarcomas, chordomas, lymphomas, and, in the elderly, plasmacytomas. Persistent pain, nocturnal accentuation of pain, and restriction in spine mobility are common features of the primary neoplasms and, for that matter, of metastatic tumor or infection.

Primary tumors, albeit rarely, do occur within the canal as well. Extradural tumors present with pain that is often more prominent at rest and often radicular and less likely to exhibit a prominent mechanical component. Intradural tumors are more insidious; pain is less localizing, and neurologic signs are more prominent.

Cauda equina tumors present as poorly localizing low back pain, often and peculiarly causing the patient to sit in a chair rather than choose recumbency, when not pacing the floor at night. Neurologic compromise from any destructive process of the cauda equina or conus medullaris places sphincter control at risk and can cause saddle anesthesia.4

Cauda equina tumors present as poorly localizing low back pain, often and peculiarly causing the patient to sit in a chair rather than choose recumbency, when not pacing the floor at night. Neurologic compromise from any destructive process of the cauda equina or conus medullaris places sphincter control at risk and can cause saddle anesthesia.4

These are the settings in which axial imaging is to be pursued. Plane radiographs are limited in sensitivity but convenient and inexpensive. Remember, one is seeking bony destruction; the nearly ubiquitous degenerative changes are nonspecific and therefore uninformative.5 Metastatic tumors have some predilection for the posterior elements so that one should focus on pedicle structures. Infection targets the disc space and can sweep across the interspace destroying juxtaposed end plates. Neoplasia, with the exception of lymphoma and myeloma, generally spares the disc space. The primary osseous neoplasias are often discernible on plane films as destructive lesions; lesions within the canal are seldom apparent. Scintiscanning (particularly if sensitivity is enhanced by the single-photon emission computed tomography [CT] technique) has near perfect sensitivity for any of the processes that impinge on bony structures. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) approach this sensitivity and have great specificity for all infectious and neoplastic processes of the axial skeleton. Furthermore, CT-guided needle biopsy is usually feasible, safe, and diagnostic.

The Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies

A century has passed since the description of ankylosing spondylitis by Bechterow and by Pierre Marie and Strumpell.6 But the concept that this was a clinical entity, and not just a form of rheumatoid arthritis, yielded slowly to a persuasive body of clinical observation and only attained general recognition in the United States in the 1960s.7 The clinical proponents were clearly prescient; any doubt faded when it was demonstrated that ankylosing spondylitis and its clinically related diseases, the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, were in linkage disequilibrium with the type 1 human histocompatibility antigen, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27. Because only the cluster of symptoms and signs recognized as the seronegative spondyloarthropathies are associated with this particular gene and its product, the distinction from all other rheumatic diseases is incontrovertible.

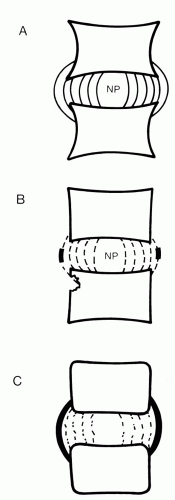

The common denominators of this spectrum of illness are encompassed in the diagnostic rubric seronegative spondyloarthropathies. First, these patients have a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease with no consistent serologic markers; for example, both rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies are undetected by routine testing. More germane to our considerations, these patients have in common some degree of inflammatory destructive disease of the joints of the spine, a spondyloarthropathy. The involvement always targets the sacroiliac joints, first the more caudal diarthrodial portion with its hyaline cartilage and later the rostral fibrous joint. Early on there is erosion demonstrated radiographically as “pseudo-widening” of the joints. Later there is ankylosis. The disease also targets the discs in a fashion that is specific for this spectrum of disease. The earliest inflammation and structural

alteration are at the site of insertion of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosis into the vertebral body (Fig. 6.1). Wherever collagen fibers (from a disc, joint capsule, or tendon) anchor in bone, the fibers are called Sharpey’s fibers, and the anatomic site of anchorage is called an enthesis. For this reason, much of the musculoskeletal pathoanatomy of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies has been termed enthesopathy, whether it occurs in the spine or elsewhere. For example, the external aspect of the pelvis is covered with entheses; spondyloarthropathies can lead to inflammatory reactions of the periosteum demonstrated radiographically as “whiskering.”

alteration are at the site of insertion of the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosis into the vertebral body (Fig. 6.1). Wherever collagen fibers (from a disc, joint capsule, or tendon) anchor in bone, the fibers are called Sharpey’s fibers, and the anatomic site of anchorage is called an enthesis. For this reason, much of the musculoskeletal pathoanatomy of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies has been termed enthesopathy, whether it occurs in the spine or elsewhere. For example, the external aspect of the pelvis is covered with entheses; spondyloarthropathies can lead to inflammatory reactions of the periosteum demonstrated radiographically as “whiskering.”

TABLE 6.1. FEATURES OF THE ILLNESS ASSOCIATED WITH THE SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES THAT ARE UNUSUAL IN REGIONAL LOW BACK PAIN | |

|---|---|

|

The illness associated with this spondyloarthropathy is backache. However, the complaint is distinctive from the illness afflicting most patients with regional low back pain. Table 6.1 lists the five features of the backache of spondyloarthropathy that distinguishes it from regional backache in the context of a diagnostic evaluation in one referral practice.8 The utility of these putative discriminators depends on the prior probability of the prevalence of the spondyloarthropathies in a particular population and thus depends on the setting in which they are applied. Without a high prior probability, as one might expect in some rheumatology practices, they have little precision. After all, the prevalence of regional backache is so enormous that atypical presentations that mimic inflammatory spondyloarthropathy may well overwhelm typical presentations of spondyloarthropathy.9 Nonetheless, they retain some usefulness in the diagnostic evaluation of any person who has chosen to be a patient with backache. More useful is a quest for associated extraspinal manifestations of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies that, when present, greatly enhance diagnostic certainty. Several of these are listed in Table 6.2. It is clear from this list that the seronegative spondyloarthropathies include ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, and the reactive arthritides, the spondylitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis. Whether these are a spectrum of a single disease or the spondyloarthropathy is a complicating feature in genetically susceptible patients with different diseases is not established.

TABLE 6.2. EXTRASPINAL MANIFESTATIONS OF THE SERONEGATIVE SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES | |

|---|---|

|

Diagnostic certainty requires radiographic documentation of sacroiliitis with or without an enthesopathy. Because the spondyloarthropathies can be symptomatic for decades without radiographic change, particularly in women, the diagnosis is often but a clinical postulate. When full blown, there is little doubt. But when there are no radiographic stigmata, one is left with but a clinical hypothesis. Even tissue typing offers little assistance. After all, the majority of people with HLA-B27 are spared a spondyloarthropathy. Furthermore, a significant minority of patients with spondyloarthropathy (5%-10% of patients with classic ankylosing spondylitis to 40% of patients with Reiter’s syndrome) lack this haplotype. Tissue typing is useless as a screening tool and is marginal as a diagnostic aid.

As a result of the honing of the clinical definition of the spondyloarthropathies and the existence of an associated genotype, much has been learned of the epidemiology of this spectrum of disease. HLA-B27 is found in some 8% of American whites; it is found in nearly 90% of American whites with classic Marie-Strumpell ankylosing spondylitis. But not all people with the B27 histocompatibility antigen are afflicted, only approximately 1%. For American whites, the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis is approximately 0.1%. Nearly all of these people bear the HLA-B27 tissue type. In populations in whom the prevalence of B27 is higher, so is the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis. For example, some 50% of Haida Indians in the Pacific Northwest are positive for B27, and a correspondingly high prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis is observed (˜6%). Conversely, the antigen is infrequent in American blacks, only 2%, and the disease prevalence is closer to 0.01%. The traditional teaching is that ankylosing spondylitis is far more likely to afflict men with sex ratios as high as 10:1. However, that has not held up in systematic studies, some of which suggest more equal prevalence between sexes, particularly in the spondyloarthropathies other than classic ankylosing spondylitis. Ankylosing spondylitis occurs in childhood when it usually presents in boys as knee oligoarthritis; back pain is not a prominent feature. Obviously, the clinician faced with a patient with back pain should remain vigilant in terms of this diagnosis. Its prognosis and management are different from that for regional low back pain.

REGIONAL LOW BACK PAIN WITHOUT RADICULOPATHY

Diagnosis

Like it or not, cognizant or not, the treating physician can do no better than make a generic illness-based diagnosis of “regional low back pain” in anyone who presents with regional backache. This is not to trivialize the labeling; it is anxiety provoking for the physician who is admitting ignorance while accepting responsibility for choosing or not choosing to exclude diseases that present as low back pain. The laity need to be educated in the reality that if their chief complaint, backache, leads to a valid diagnosis of “regional back pain,” they should feel reassured and well served. Any attempt to make a primary diagnosis, to define the cause of a particular episode of regional low back pain, will succumb to stochastic realities. Some physical findings such as spinal range of motion and distraction can be rendered reliable

with effort.10 Most “signs” that involve prodding and probing the low back are unreliable. And all signs, even diminished range of motion and lumbosacral list,11 are nonspecific in the setting of regional low back pain. Imaging techniques have proven even more disappointing. Some, such as thermography, are simply worthless.12 Other contemporary imaging modalities can provide marvelous, seductively detailed anatomic definition that, in the adult, offers nothing for the differential diagnosis of regional low back pain. The likelihood of demonstrating pathology increases with age to become ubiquitous in the later decades. However, the specificity of any degenerative finding decreases with age so that the pathoanatomic insights are rendered clinically useless. This statement pertains to plane radiographs, CT,13 and MRI.14 In other words, any degenerative image found in a population with regional low back illness can be found in a pain-free population matched for all other parameters with sufficient likelihood to render pathogenetic inferences effete. An equally cogent deduction is that any degenerative change discerned does not alter the likelihood of remission of the symptom of low back pain. Finally, any degenerative change discerned will persist even after the symptoms have subsided.

with effort.10 Most “signs” that involve prodding and probing the low back are unreliable. And all signs, even diminished range of motion and lumbosacral list,11 are nonspecific in the setting of regional low back pain. Imaging techniques have proven even more disappointing. Some, such as thermography, are simply worthless.12 Other contemporary imaging modalities can provide marvelous, seductively detailed anatomic definition that, in the adult, offers nothing for the differential diagnosis of regional low back pain. The likelihood of demonstrating pathology increases with age to become ubiquitous in the later decades. However, the specificity of any degenerative finding decreases with age so that the pathoanatomic insights are rendered clinically useless. This statement pertains to plane radiographs, CT,13 and MRI.14 In other words, any degenerative image found in a population with regional low back illness can be found in a pain-free population matched for all other parameters with sufficient likelihood to render pathogenetic inferences effete. An equally cogent deduction is that any degenerative change discerned does not alter the likelihood of remission of the symptom of low back pain. Finally, any degenerative change discerned will persist even after the symptoms have subsided.

Low specificity limits the diagnostic utility of MRI scans as much as it limits that of radiographs. MRI cannot be used to predict back pain.15 MRI is not even sensitive to anatomic changes that might correlate with new symptoms.16 Cost has little to do with cost/effectiveness if imaging is ineffective. I suspect none of this is lost on many primary care physicians who feel compelled to order these studies despite the data. This may reflect their concern that the evidence is based on an experience that might not encompass their patients’ presentations.17 Such a stochastic rationale aside, imaging the spine is the proclivity of medical practitioners and the expectation of their patients for generations. Imaging might not facilitate return to well-being, but it certainly contributes to patient satisfaction.18 Is this a valuable outcome? Or is this sense of satisfaction contributing to the persistence of illness? The discourse that follows imaging always relates to the demonstrable pathoanatomy. Satisfying or not, this discourse is associated with an exacerbation of pain19 and an increased likelihood of surgery.20 Surgery for regional back pain is no more supportable on evidentiary grounds than is imaging.21 Imaging is not serving as a diagnostic modality in this setting. It is one element of a complex treatment act that endows patients with unfounded notions of pathophysiology and enriches their narrative of distress with the private vocabulary of the treating professional. Patients are forever changed by these experiences, too few for the better.22 Whatever “satisfaction” is derived from undergoing imaging studies does not stop one third of primary care patients with back pain from using multiple practitioners.23 Imaging is not a diagnostic modality in this context; it is symbolic of the flawed logic that renders the prognosis for the return to a sense of well-being so dismal. We shall return to these thoughts shortly.

The Canadian clinical community seems to have heard this message24 and is using plane radiography even more sparingly than the proscription offered by a U.S. committee charged with providing evidence-based guidelines.25 Perhaps Canadian primary care practitioners are aware that imaging for regional low back pain is worse than useless. It is counterproductive both in time and in one’s ability to

promote in the patient a perception that regional low back pain is an intermittent and remittent illness and not a reflection of a “bad back.”

promote in the patient a perception that regional low back pain is an intermittent and remittent illness and not a reflection of a “bad back.”

Mention should be made of discography, a diagnostic modality knocking at the door of the archives. The technique involves inserting a needle into a disc to introduce radio-opaque dye. The early interpretation was based on the geometry of the space occupied by the introduced dye, but that interpretation was soon skewered by science; the distribution is not specific for axial pain and often an artifact resulting from pushing the dye into the disc. The procedure is never pleasant. However, its proponents came to believe that if the pain they induced reproduced the patient’s symptoms, the study was localizing in terms of the cause of the patient’s pain. This “provocative discography” has also been skewered by systematic studies.26,27

Promulgating this perception of healing should color the entire interaction with the patient. It is to be the logical conclusion of the process of history and of physical examination. In the history, little is dissuasive of this conclusion aside from the features discussed previously that pertain to systemic disease.28 The physical examination is useful only in that one can be reassured regarding major neurologic compromise and relevant underlying diseases such as pelvic or prostatic pathology. Findings on physical or imaging examinations cannot be used to support inferences regarding the pathogenesis of the regional low back pain. Regardless of all this uncertainty, prognostic inferences can be drawn,29 and counseling regarding the extensive menu of therapeutic alternatives can be offered, taking advantage of a voluminous experimental literature. The initial interview and examination allow one to make a presumptive diagnosis of regional back pain and thereby to disabuse the patient of any evil implication of all the uncertainties. It is essential that the patient appreciate the concept of a diagnosis of exclusion and the need to avoid testing where the yield of meaningful information is vanishingly low. If the patient does not arrive at such an understanding at the first evaluation, he or she will leave the office, participating in a diagnostic evaluation that develops a life of its own; the patient will focus on every nuance of his or her illness as meaningful and fall prey to any and all who offer the promise of greater certainty or even empiric therapy. Such a fate is a match for “defensive medicine” in rendering the patient more ill.

Therapy

Even in the industrial setting, the mainstay of therapy for the acute30 or subacute backache31 is to demedicalize the event. In all likelihood, the process is self-limited; some 80% of patients are well or nearly so in 2 weeks, and at least 90% are well at 2 months. Furthermore, although there is considerable likelihood of recurrence,32 nearly all are left no worse for wear. Finally, with certain exceptions in both directions, the natural history cannot be meaningfully perturbed by interventions. The upshot is that the patient should be made to commandeer this experience, to use his or her own best judgment.33 No patient should ever be rendered so anxious, if not fearful, that he or she craves “the diagnosis” and then “the cure” to become

accepting of any remedy proffered by the enormous enterprise waiting to help. Educating and dissuading the patient from this traditional algorithm is a challenging yet critical undertaking; most who choose to be patients with a backache bring to the medical interaction presuppositions and expectations that initiate this algorithm. Therefore they must be disabused. But they must, at the same time, be offered a “port in the storm” where both the intensity of the discomfort and the limitation of activity are recognized, discussed, and put into perspective.34

accepting of any remedy proffered by the enormous enterprise waiting to help. Educating and dissuading the patient from this traditional algorithm is a challenging yet critical undertaking; most who choose to be patients with a backache bring to the medical interaction presuppositions and expectations that initiate this algorithm. Therefore they must be disabused. But they must, at the same time, be offered a “port in the storm” where both the intensity of the discomfort and the limitation of activity are recognized, discussed, and put into perspective.34

Nearly all available interventions have been subjected to clinical trials of some description. There are more than 1000 relevant randomized, controlled trials. Few of these trials escape critical review unscathed; many are simply uninterpretable. Nonetheless, there is more than enough information to place most of the therapeutic options for acute low back pain into perspective. The exercise of putting this literature into perspective requires assessing the quality of each article to generate levels of confidence in the inferences one is willing to derive. I have pursued this exercise in my fashion for more than two decades, publishing my first overview in 197935 and serially updating in monographs and articles ever since. There is no “right” way to analyze such a literature; all articles are flawed, some seriously. Realize that a methodologically perfect study requires a highly defined protocol applied to a highly defined population; even if such were feasible, one could question whether the results would generalize to protocols that are slightly different or to practice settings that are dramatically different. Nonetheless, I have been joined in this exercise by others, including committees of investigators charged with extracting inferences from the evidence in the literature. Notable among these is a report of a committee convened in Quebec36 almost two decades ago, another “consensus” underwritten by the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research 10 years ago and to which I served as consultant.25 The exercise has since been replicated around the world by scientists convened by governmental agencies to provide evidence-based guidelines for the management of low back pain in occupational37 and non-occupational primary care38 settings. A Dutch systematic review39 and one from Sweden40 are exemplary of the latter.

All this effort is under the banner of “evidence-based medicine,” a shibboleth that certainly is a noble goal but not without limitations, as I will discuss shortly. Since 1992, there has been an international collaborative effort to examine the scientific basis of all clinical practice. This Cochrane Collaboration, still funded by moneys from participating governments, has recruited thousands of physicians and scientists and established 50 groups charged with the tasks of identifying critical issues in their clinical disciplines and examining the scientific evidence that informs these issues in an ongoing fashion. The work of the Cochrane Back Review Group41 is particularly relevant to our discussion.

In Chapter 2 I described my current approach to the management of acute regional low back pain. What follows is the update on my evaluation of the literature for each of the major modalities purveyed and prescribed by others. I rely heavily on the primary literature as I read it myself, but I am influenced by the systematic reviews and guidelines produced by others. However, I also rely on my own judgment and experience and do not dismiss the input of peers and students. I am not

embarrassed by this admission of potential prejudice; it is central to the art of medicine and defensible if it is recognized and admitted. Do not think for one moment that the force of personality does not influence the direction of systematic reviews, even when undertaken by committee42; there is plenty of room for value judgments regarding the quality of articles, their generalizability, and their importance. In fact, the conclusions derived from Cochrane reviews are dependent on the fashion in which the group establishes “levels of evidence,” that is, the criteria by which particular studies are held to be persuasive.43 Not surprisingly, the method guidelines for systematic reviews established by Cochrane Review Groups are a moving target, including for the Back Review Group.44 That is why physicians in general reflexively tend to cast a jaundiced eye on “practice guidelines,” even those claiming to be evidence based.45

embarrassed by this admission of potential prejudice; it is central to the art of medicine and defensible if it is recognized and admitted. Do not think for one moment that the force of personality does not influence the direction of systematic reviews, even when undertaken by committee42; there is plenty of room for value judgments regarding the quality of articles, their generalizability, and their importance. In fact, the conclusions derived from Cochrane reviews are dependent on the fashion in which the group establishes “levels of evidence,” that is, the criteria by which particular studies are held to be persuasive.43 Not surprisingly, the method guidelines for systematic reviews established by Cochrane Review Groups are a moving target, including for the Back Review Group.44 That is why physicians in general reflexively tend to cast a jaundiced eye on “practice guidelines,” even those claiming to be evidence based.45

I will reference individual articles and systematic reviews that I find particularly interesting or that have been particularly influential. The systematic reviews provide comprehensive reference lists for any reader seeking such.

Rest

Therapeutic rest was a mainstay for many illnesses in the early decades of this century. For most conditions, it has been relegated to history. It can be discarded for acute low back pain. Certainly recumbency unloads the lumbosacral spine, but only if one is fully recumbent. One is better off standing, or sitting erect, than propping up in bed. No wonder nearly all of us are noncompliant with enforced bed rest. In addition, it has not been possible to demonstrate enhanced healing rates with prescribed bed rest, only increased absenteeism from work.46,47 Suggesting postures to avoid, such as anterior sitting (e.g., slouching forward over one’s desk), is far more sensible than proscribing motion or function. The most compelling evidence supports the advice to stay active,48 to get on with life as best as possible until the discomfort subsides and the episode slips into memory.

Pharmacologic Agents

There are dozens of controlled trials incorporating various analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), benzodiazepines, colchicine, so-called muscle relaxants, and narcotics. NSAIDs offer modest short-term symptomatic relief for patients with acute low back pain. It has not been possible to convincingly demonstrate differential effectiveness among the various NSAIDs or any advantage over acetaminophen.49

“Muscle relaxants” have long been touted for backache and are commonly prescribed. I am not certain that there is such a category of agent because none has a direct effect on the electromyography of the paraspinous musculature. The medicines prescribed under this rubric are generally either benzodiazepines or a variety of drugs, most notably cyclobenzaprine, which is structurally similar to the tricyclic antidepressants and is a potent sedative, and carisoprodol, which is a less potent sedative. There are other agents that have some effectiveness in reducing

the spasticity that is a feature of multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and spinal cord injuries, but these are no more effective and less frequently prescribed in the setting of regional back pain. The commonly used “muscle relaxants” are effective in the setting of regional back pain but mainly by virtue of sedation.50 My advice to patients is that coping with acute low back pain is not rendered easier by being foggy headed. I do not prescribe the agents.

the spasticity that is a feature of multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and spinal cord injuries, but these are no more effective and less frequently prescribed in the setting of regional back pain. The commonly used “muscle relaxants” are effective in the setting of regional back pain but mainly by virtue of sedation.50 My advice to patients is that coping with acute low back pain is not rendered easier by being foggy headed. I do not prescribe the agents.

Foggy headedness is only one of the reasons I do not prescribe opiates for acute back pain. There is no systematic review of the evidence to cite against which I can play off my therapeutic posture. That is because there are no relevant scientific studies on which to base such an exercise. The literature is a compendium of opinion and diatribe. My therapeutic posture is informed by this debate and by my understanding of the risks and benefits. I am unwavering in my negotiation with any patient for whom opiates seem the logical salve. As we shall discuss in Section III, patients with chronic low back pain, and other chronic regional musculoskeletal disorders, are often burdened and stigmatized by opiate addiction to such a degree that diminishing dependency is at the forefront of management. No patient with chronic back pain would be burdened with adverse illness behaviors related to opiate dependence were it not for the decision to treat acute back pain with opiates in the first place. Therein lays the conundrum. I am ethically bound as a physician, and licensed, to alleviate pain and suffering. For the patient suffering a painful death from metastatic cancer, alleviating the pain and palliating the suffering with opiates is my calling. For the patient with postoperative pain, in which case the pathogenesis is both obvious and self-limited, palliating the pain and alleviating the suffering with opiates is my calling. However, my calling is different in the setting of regional musculoskeletal pain. I can alleviate the pain of acute backache and chronic backache with opiates. However, it is less clear that I can alleviate the suffering (this distinction was developed in Chapter 3). In fact, the regulation of the prescription of opiates during the course of the 20th century has been driven by the impression that attempting to alleviate the pain of regional musculoskeletal disorders with opiates is confounding if not counterproductive.51,52 The argument set forth in Chapters 2, and which will be revisited repeatedly in Section III, is that the complaint of backache in the western world must be viewed as a semiotic. Yes the patient has back pain. However, the chief complaint is not simply that the back hurts; it is that the back hurts, but on this occasion coping is overwhelmed. Seldom is the quantity of pain inherent to the backache as limiting as factors in life that are compromising coping. These are the factors that render the back pain insufferable. Plying the patient with opiates obfuscates that insight. Rather, the patient learns that the pain and its underlying pathoanatomy are so terrible as to warrant the same desperate attempt at palliation as if terminal cancer were the evil. Any notion that psychosocial confounders are relevant becomes illogical. Furthermore, when opiates prove no match for the pain, predictably because they are no match for the psychosocial confounders, the patient is more amenable to aggressive diagnostics and intervention and more desperate yet when they fail to provide relief. That is why the initial negotiation regarding opiates rests on the thinnest of ice.

That is why I am unwavering in my refusal to resort to opiates for relief of pain; the risk of increasing the suffering is too unappealing a tradeoff.

That is why I am unwavering in my refusal to resort to opiates for relief of pain; the risk of increasing the suffering is too unappealing a tradeoff.

Clearly, most pharmaceuticals are more consistent and impressive in their toxicities than in differential benefit. Rather than risk a cloudy sensorium, obstipation, or the implication that the illness is of sufficient severity to warrant desperate medicines, the case is easily made for empathy, reassurance, psychologic support, and a mild analgesic such as acetaminophen along with warm showers. Bathing, regardless of the liquid or its turbulence, can be limited by the biomechanical challenge of entering or leaving the tub with a backache. Forewarn the patient. Speaking of bathing, spas offering balneotherapies seem to soothe the aching backs53 of those who live in a culture where the body politic supports such an investment.54

Exercises

There are advocates for flexing. There are advocates for extending. There are advocates for isotonic exercises and for combinations. Each has a theory, each is offered with zeal, and each has a following. Furthermore, several regimens are supported by trials showing a degree of benefit. However, there are two trials demonstrating harm from exercise regimens for acute low back pain. For that reason, an easily defensible approach is to suggest exercises ad lib and postures to avoid, and to suggest that returning to full function, to ordinary activity, even to work, is to be encouraged as early as possible even before complete remission has supervened. There is impressive evidence supporting such advice.55 There is no impressive evidence that specific exercises are effective for the treatment of acute low back pain.56 The role of exercise programs in the management of workers disabled with chronic low back pain will be discussed next, but the context necessary to understand the limitations of this approach is developed in Section III.

Physical Modalities

Most of the menu of physical modalities has escaped critical testing. Many physical treatments are so dependent on idiosyncratic human interactions that controlled trials are inherently flawed.57 Benefit for massage therapy may remain unprovable58 because of that. How can one design a trial that distinguishes between the effects of the massaging and the masseuse? Furthermore, it is clear that patients’ expectations influence clinical outcomes independently of the treatment itself. In a trial comparing massage with acupuncture for low back pain, those patients randomized to a particular treatment who expected benefit from that modality beforehand were more likely to perceive benefit afterward.59 Designing a control intervention, particularly a sham intervention, for a trial of a physical modality is a challenge that is often insurmountable.

The transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit has performed poorly in several randomized controlled trials for chronic low back pain60 and is not promising for acute low back pain either. There are enough data on the TENS unit that a group of investigators had the temerity to undertake a meta-analysis.61

This is not a systematic review; this is a meta-analysis. For reasons discussed previously, I am wary of systematic reviews, but I am very wary of meta-analyses. In fact, I do not think meta-analyses ever offer a valid answer to clinical uncertainty despite the effort expended on them. They are only undertaken when the literature is contradictory, often because the clinical outcome measured is slight—a percent or three effect on the outcome one way or the other. If the literature were crystal clear, if there were a few replicate compelling studies, there would be no need to try to extract some hidden insight from the cacophony. Systematic analysis is an exercise in which investigators find all articles relevant to a particular topic and rate them according to their methodologic quality. Then they determine the number of good articles that are positive versus the number that are negative and draw some conclusion. However, nearly all articles are flawed to some degree and in some way. Deciding which flaws are most egregious is an exercise in small group psychology, not science. It is this exercise that leads to the conclusion. Thank you, but I prefer to do my own reading. Meta-analyses go a step further. They are designed to try to collect all the data from the “good” trials into a single melded experiment. The investigators go to great lengths to cope with differences in design and outcome measures, lengths that involve intricate massaging of the data. They perform sensitivity analyses to see if one data set or one assumption is weightier than another. They even have devised statistics to probe for publication bias, that is, the greater likelihood for positive studies to be submitted, accepted, and published than negative studies. Seldom is the result of a meta-analysis more compelling than the conclusions from a systematic review. Sometimes after they are finished mixing and stirring the “data salad,” they find that they have learned nothing. That happened in the meta-analysis of the TENS data. My philosophy as to whether literature can salve clinical uncertainty is harsh and rigorous. If the literature is shallow and inconsistent, a meta-analysis offers nothing. There is no result of sufficient magnitude to be believable to be teased out of the data that exhibits marginal effects and inconsistencies.

This is not a systematic review; this is a meta-analysis. For reasons discussed previously, I am wary of systematic reviews, but I am very wary of meta-analyses. In fact, I do not think meta-analyses ever offer a valid answer to clinical uncertainty despite the effort expended on them. They are only undertaken when the literature is contradictory, often because the clinical outcome measured is slight—a percent or three effect on the outcome one way or the other. If the literature were crystal clear, if there were a few replicate compelling studies, there would be no need to try to extract some hidden insight from the cacophony. Systematic analysis is an exercise in which investigators find all articles relevant to a particular topic and rate them according to their methodologic quality. Then they determine the number of good articles that are positive versus the number that are negative and draw some conclusion. However, nearly all articles are flawed to some degree and in some way. Deciding which flaws are most egregious is an exercise in small group psychology, not science. It is this exercise that leads to the conclusion. Thank you, but I prefer to do my own reading. Meta-analyses go a step further. They are designed to try to collect all the data from the “good” trials into a single melded experiment. The investigators go to great lengths to cope with differences in design and outcome measures, lengths that involve intricate massaging of the data. They perform sensitivity analyses to see if one data set or one assumption is weightier than another. They even have devised statistics to probe for publication bias, that is, the greater likelihood for positive studies to be submitted, accepted, and published than negative studies. Seldom is the result of a meta-analysis more compelling than the conclusions from a systematic review. Sometimes after they are finished mixing and stirring the “data salad,” they find that they have learned nothing. That happened in the meta-analysis of the TENS data. My philosophy as to whether literature can salve clinical uncertainty is harsh and rigorous. If the literature is shallow and inconsistent, a meta-analysis offers nothing. There is no result of sufficient magnitude to be believable to be teased out of the data that exhibits marginal effects and inconsistencies.

Various forms of traction have been subjected to trials, most of which are difficult to interpret because of lack of definition of the quality of illness experienced by the subjects or lack of reliability or validity of the outcome measures. In overview and confirmed in a trial that suffers far less from flaws in design,62 traction is unimpressive if not useless beyond enforcing bed rest and rendering the patient totally passive and nonfunctional. Finally, attempts to provide mechanical support by applying corsets to reduce the load on the spine offer nothing more than false security and may encourage dependency in patients with chronic pain. Leather belts of various kinds are de rigueur for bodybuilders and have found their way into industry for back pain prophylaxis with little substantive supporting data.63 By the late 1990s, it was common to see those employed in materials-handling tasks wearing back belts. Leading epidemiologists64,65 pointed to the limitations of the available science and argued that it was premature to abandon back belts. Thanks to more recent and compelling science,66 back belts should be relegated to history along with the pathogenetic inferences they represented.67

Spinal Manipulation

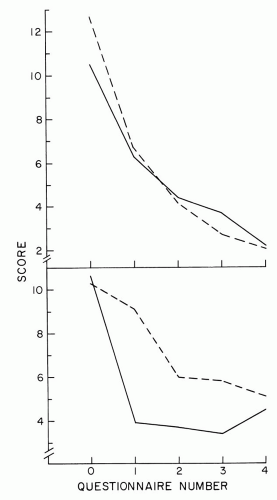

As mentioned in Chapter 1, benefit from spinal manipulation is demonstrable (Fig. 6.2), but only for one subset of people with uncomplicated acute low back pain (younger individuals hurting for at least 2 weeks but no more than 4 weeks), and even then the benefit is modest at best.68 This form of manipulation, a form that has been the mainstay of osteopathic and other sectarian practitioners who practice manual therapy, can be shown to decrease the experience of illness as long as the subjects have uncomplicated subacute back pain.69,70 It is far less clear that spinal

manipulation has anything to offer patients with backache who have more persistent or more confounded illnesses. It is also unclear whether repeated manipulations add anything71 and quite clear that spinal manipulation has nothing to offer for illness other than acute regional disorders of the spine. Furthermore, there is no evidence that spinal manipulative therapy is superior to other standard treatments for patients with acute or chronic low back pain.72,73

manipulation has anything to offer patients with backache who have more persistent or more confounded illnesses. It is also unclear whether repeated manipulations add anything71 and quite clear that spinal manipulation has nothing to offer for illness other than acute regional disorders of the spine. Furthermore, there is no evidence that spinal manipulative therapy is superior to other standard treatments for patients with acute or chronic low back pain.72,73

FIGURE 6.2. The University of North Carolina Trial of Spinal Manipulation. Mean score on a questionnaire that quantifies the magnitude of illness from acute low back pain experienced by the subjects in the University of North Carolina study of spinal manipulation. The questionnaire was administered just before entry in the study and at the time of telephone follow-up every 3 days (±1 days) after treatment. Results for subjects randomized to be treated by mobilization (broken lines) or spinal manipulation using a single long leverarm, high-velocity technique (solid lines). All four groups were indistinguishable at entry and at 2 weeks after treatment. Results for the stratum wherein all subjects had a backache for less than 2 weeks at the time of entry into the protocol (top). Stratum for subjects who experienced pain for 2 to 4 weeks (bottom). Treatment effect was only discernible in the latter stratum (P = .009). In that stratum, those who underwent manipulation achieved a 50% reduction in score more rapidly than those who underwent mobilization, although the latter caught up by 2 weeks. (Reprinted with permission of the publisher of Spine from the original publication: Hadler NM, Curtis P, Gillings DB, et al. A benefit of spinal manipulation as adjunctive therapy for acute low back pain: a stratified controlled trial. Spine 1987;12: 703-6.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|