Accelerated cardiometabolic disease is a serious health hazard after spinal cord injuries (SCI). Lifestyle intervention with diet and exercise remains the cornerstone of effective cardiometabolic syndrome treatment. Behavioral approaches enhance compliance and benefits derived from both diet and exercise interventions and are necessary to assure that persons with SCI profit from intervention. Multitherapy strategies will likely be needed to control challenging component risks, such as gain in body mass, which has far reaching implications for maintenance of daily function as well as health.

Key points

- •

Accelerated cardiometabolic disease is a serious health hazard after spinal cord injuries (SCI).

- •

Lifestyle intervention with diet and exercise remains the cornerstone of effective cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) treatment.

- •

Behavioral approaches enhance compliance and benefits derived from both diet and exercise interventions and are necessary to assure that persons with SCI profit from intervention.

- •

Multitherapy strategies will likely be needed to control challenging component risks, such as gain in body mass, which has far reaching implications for maintenance of daily function as well as health.

- •

In cases where lifestyle approaches prove inadequate for risk management, pharmacologic control is now available through a population-tested monotherapy.

- •

Use of these clinical pathways will foster a more effective health-centered culture for stakeholders with SCI and their health care professionals.

Cardiometabolic risks in SCI

Health hazards posed by all-cause cardiovascular disease (CVD) and co-morbid endocrine disorders are widely reported in persons with spinal cord injuries (SCI). The contemporary descriptor cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) represents a complex array of these hazards, which by evidence-based clinical diagnosis encompasses 5 component risks of central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low-plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), hypertension, and fasting hyperglycemia ( Table 1 ). Left untreated, these risks promote atherosclerotic plaque formation and premature CVD, and when identified in clusters of 3 or more risks, confer the same clinical threat as frank diabetes or extant coronary artery disease.

| Risk | Criterion | |

|---|---|---|

| ATP III | WHO | |

| (Abdominal) obesity |

|

|

| Triglycerides |

| |

| HDL-cholesterol |

|

|

| Blood pressure |

|

|

| Hyperglycemia |

|

|

| Microalbuminuria |

|

|

Special Concerns for Persons with SCI (Accelerated Risk and Specific Targets)

Convincing evidence supports the population-specific threat to persons with SCI for an accelerated trajectory of CMS, which is typically seen as component risks of central obesity, impaired fasting glucose and frank diabetes, dyslipidemia, and (depending on the nature and level of injury) hypertension. Blood pressure, however, is a 2-sided issue in the SCI population. Persons with high-level SCI (T6 or above, where sympathetic nervous system control is likely compromised ) frequently suffer from hypotension. Persons with lower-level injuries have similar hypertension issues as the general population. Target levels for markers of these CMS risks have been established (see Table 1 ) for the general population but not specifically for SCI. In the absence of specific recommendations, general targets for lipid and glycemic markers may be adequate for persons with SCI. However, standard categories for common surrogate measures of obesity, such as waist circumference (WC) or body mass index (BMI), are not applicable for SCI and should be adjusted to greater than 94 cm WC and ≥22 kg/m 2 BMI, respectively.

Cardiometabolic risks in SCI

Health hazards posed by all-cause cardiovascular disease (CVD) and co-morbid endocrine disorders are widely reported in persons with spinal cord injuries (SCI). The contemporary descriptor cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) represents a complex array of these hazards, which by evidence-based clinical diagnosis encompasses 5 component risks of central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low-plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), hypertension, and fasting hyperglycemia ( Table 1 ). Left untreated, these risks promote atherosclerotic plaque formation and premature CVD, and when identified in clusters of 3 or more risks, confer the same clinical threat as frank diabetes or extant coronary artery disease.

| Risk | Criterion | |

|---|---|---|

| ATP III | WHO | |

| (Abdominal) obesity |

|

|

| Triglycerides |

| |

| HDL-cholesterol |

|

|

| Blood pressure |

|

|

| Hyperglycemia |

|

|

| Microalbuminuria |

|

|

Special Concerns for Persons with SCI (Accelerated Risk and Specific Targets)

Convincing evidence supports the population-specific threat to persons with SCI for an accelerated trajectory of CMS, which is typically seen as component risks of central obesity, impaired fasting glucose and frank diabetes, dyslipidemia, and (depending on the nature and level of injury) hypertension. Blood pressure, however, is a 2-sided issue in the SCI population. Persons with high-level SCI (T6 or above, where sympathetic nervous system control is likely compromised ) frequently suffer from hypotension. Persons with lower-level injuries have similar hypertension issues as the general population. Target levels for markers of these CMS risks have been established (see Table 1 ) for the general population but not specifically for SCI. In the absence of specific recommendations, general targets for lipid and glycemic markers may be adequate for persons with SCI. However, standard categories for common surrogate measures of obesity, such as waist circumference (WC) or body mass index (BMI), are not applicable for SCI and should be adjusted to greater than 94 cm WC and ≥22 kg/m 2 BMI, respectively.

Therapeutic lifestyle intervention

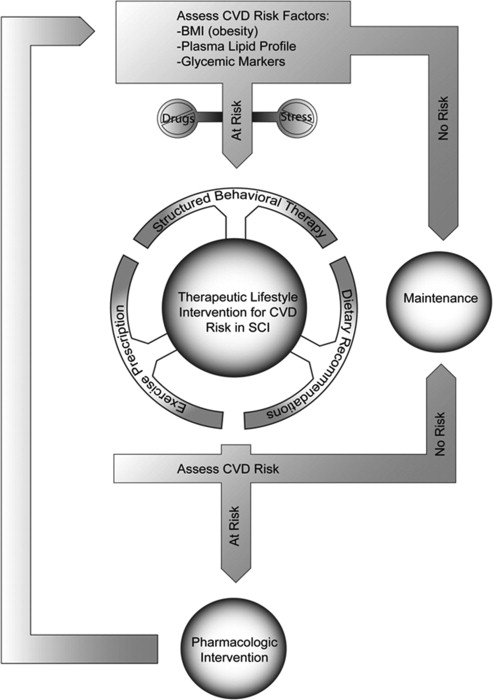

Guideline-driven interventions to reduce CMS risks follow a pathway that first eliminates drugs and biologic agents that might be causing the CMS, which would include tobacco use. Otherwise, little in the pharmacopeia of persons with SCI would cause or worsen the CMS. Thereafter, comprehensive therapeutic lifestyle intervention (TLI) focusing on changes of dietary, exercise, and behavioral components is instituted. If these measures fail to correct the hazard, pharmacotherapy becomes the default intervention. This article provides details for each of these risk countermeasures. A clinical pathway outlining the treatment decision-making in this respect is shown in Fig. 1 .

Dietary Component of TLI

Based on information from United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010, adapted for SCI where applicable.

- •

Energy intake has to be balanced with output to avoid or reduce obesity and prevent or improve CVD risk.

- •

Diet recommendations for persons with SCI should follow general guidelines, including increasing whole grain, fruit, and vegetable intake, while reducing salt, simple sugar, saturated fat, and cholesterol intake.

- •

Specific evidence for persons with SCI is sparse and diet recommendations should follow general guidelines except for BMI targets and energy requirement estimates.

Key points

- •

Diet Considerations—Energy Balance, Body Composition, and Malnutrition

Weight maintenance or weight loss is the primary goal of most diet interventions aimed at preventing and reducing obesity and CMS risk. Even modest amounts of body weight reduction can result in marked health benefits. Energy (caloric) intake and output are the primary factors determining changes in weight and need to be balanced according to the desired goal (ie, if one desires weight loss one needs to achieve a negative balance [energy intake<energy output]). More specifically, body fat reduction while maintaining (or increasing) lean mass (ie, muscle) should be targeted in an effort to improve body composition. This goal is of particular relevance to the upper extremities in persons with SCI because upper extremity function is crucial for daily activities, pain, and independence. Weight loss achieved by reducing caloric intake usually results in 14% to 24% loss in lean tissue mass and should therefore be accompanied by an exercise regimen to avoid such losses (see exercise section). In addition to energy balance, dietary interventions should also consider specific nutrition needs to avoid malnutrition (overconsumption and underconsumption of nutrients) and promote optimal health. These key concepts and considerations are explained in detail in discussion below and summarized in Box 1 .

- •

Assess energy balance

- ○

Energy intake

- ▪

Diet analysis

- ▪

- ○

TEE

- ▪

BMR/REE

- ▪

PA/exercise

- ▪

TEF

- ▪

- ○

- •

Create caloric deficit

- ○

Reduce energy intake

- ▪

Reduce calorie-dense foods

- ▪

- ○

Increase EE

- ▪

PA/exercise

- ▪

TEF

- ▪

- ○

- •

Malnutrition

- ○

Overconsumption of macronutrients

- ▪

Fats, cholesterol, CHO

- ▪

- ○

Underconsumption of micronutrients and fiber

- ▪

Vitamin A, D, E, C, B5, and biotin

- ▪

- ○

- •

Recommended diets

- ○

Mediterranean

- ○

DASH

- ○

Assessing energy balance

To set caloric targets for weight loss or maintenance, current energy intake and output need to be assessed. The most direct way of assessing everyday energy intake is to measure all consumed foods and beverages and calculate caloric values from food labels. However, this may be cumbersome and time-consuming, particularly for persons with impaired hand function. More practical may be the use of diet recall or food frequency questionnaires (preferably with instruction from a professional ) in combination with nutrition analysis software. Multiple different analysis software packages are available including a free online calculator from the USDA (SuperTracker ).

Energy output or total energy expenditure (TEE) comprises basal metabolic rate (BMR), physical activity (PA), and energy expenditure (EE) from the breakdown, digestion, absorption, and excretion of food (summed up as the thermic effect of food, TEF). Most TEE (>80%) is accounted for by the by BMR and PA (see exercise section). Laboratory assessments of TEE are difficult and expensive and standard “field” techniques often overestimate TEE in persons with SCI. Better estimates of TEE are achieved with specific questionnaires, such as The Physical Activity Scale for Individuals with Physical Disabilities or the Physical Activity Recall Assessment for People with Spinal Cord Injury.

Creating a caloric deficit

After assessing energy balance, a caloric deficit of 300 kcal or less should be created to elicit weight loss. Ideally, this should be from a combination of reduced caloric intake and increased expenditure, although the latter may be difficult for persons with SCI (see exercise section). To achieve the caloric deficit, people should reduce or eliminate primarily energy-dense food high in components associated with elevated CMS risk, such as saturated fats/trans fats, added/refined sugars, refined grains, and alcohol, as outlined in Table 2 . Increased EE will largely depend on PA and body composition changes affecting BMR and may be difficult for persons with SCI (see exercise section). Increased TEF may contribute to a small extent. Little is known about specific foods that increase TEF, but generally TEF is higher for protein compared with other macronutrients (ie, carbohydrates and fats) and may be positively affected by certain micronutrients (reviewed in Ref. ). The latter, however, mostly lacks rigorously controlled evidence and should therefore be met with caution. Contrary to common belief, fiber does not seem to augment TEF (unless it contains high amounts of polyphenols ) but may increase fecal energy loss. Of note, people with SCI may have reduced TEF (12% of TEE vs 15% for able bodied [AB] ). Although reduction of caloric intake is the key to weight loss, it should not decrease to less than 800 kcal/d and may have to be considerably higher depending on the individual’s age, size, body composition, activity level, disease status, and other factors that affect metabolism. Reference values for age and gender have been published by the USDA but likely overestimate energy needs for persons with SCI because of their lower metabolically active mass and PA levels. Studies directly comparing resting energy expenditure (REE) between AB and persons with SCI report on average 10% lower energy requirements for adults with chronic SCI (although this difference is markedly reduced to only 1.4% when REE is normalized to body weight). Average REE for adults with chronic SCI have been reported to range from 1392 to 1855 kcal/d for men and 1042 to 1290 kcal/d for women. These values likely better represent caloric needs of persons with SCI than those published for the general population and can be used as initial targets for caloric deficits.

| Food Component Associated with CVD Risk | Examples |

|---|---|

| Saturated fat (<7% of TEE) | Animal products (except fish), coconut/palm oil, pizza, pastries, tortillas, chips, fried foods, etc. |

| Trans fats | Margarines, snack foods, pre-prepared dessert, partially hydrogenated oils, etc. |

| Added sugars | Soda/sports/energy/fruit/tea drinks, cereals, candy, desserts, etc. |

| Refined grains | Breads, pizza, pastries, tortillas, chips, pasta, prepared foods (mixed dishes), crackers, cereals, etc. |

| Alcohol (≤1 drink for women, ≤2 for men) | Beer, wine, spirits, liquors, etc. |

Malnutrition

To maximize health benefits, diet interventions need to extend beyond mere caloric balance boundaries and ensure adequate nutrient intake to avoid deficiencies. In addition, excess consumption of dietary components associated with CMS risk should be reduced or eliminated. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) have been published by the USDA. Generally, consumption of macronutrients is adequate or excessive for persons with SCI (particularly for fat and cholesterol intakes) with the exception of fiber. Fiber is of particular concern for persons with SCI because their most common lipid abnormality is low HDL and fiber consumption is positively related to HDL levels. However, high fiber intake (20–30 g/d) may stimulate undesirable changes in bowel function that differ from the non-disabled population, rendering high fiber diets impractical for persons with SCI.

Because of the general eating habits of most Americans, several micronutrients are of concern because the likelihood of deficiency is high. These nutrients include potassium, fiber, calcium, and vitamin D as well as iron and folate (women only). Several other nutrients ( Table 3 ) are of particular concern for persons with SCI because they are often underconsumed by this population (reviewed in Refs. ). In addition, sufficient consumption of biotin and vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) may also be of concern to persons with SCI, although DRIs have not been published by the USDA Dietary Guidelines.

| Nutrient, Unit | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–30 y | 31–50 y | 51+ y | 19–30 y | 31–50 y | 51+ y | |

| Vitamin A (RAE), mcg | 700 | 700 | 700 | 900 | 900 | 900 |

| Vitamin D, a mcg | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Vitamin E (AT), mg | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Vitamin C, mg | 75 | 75 | 75 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Biotin, b mcg | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Vitamin B5, b mg | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

a Assuming minimal sun exposure.

b Values are not from USDA Dietary Guidelines but based on date from Yates et al, 1998.

Correcting nutrient deficiencies/excess

If deficiencies are identified, the diet should be augmented with specific foods high in these nutrients. As mentioned above, macronutrient deficiency is rare (except for fiber) for persons with SCI, although sources of the nutrients need to be considered and should be mainly from lean meats and seafood (protein), whole grains (carbohydrates), and unsaturated fatty acids (fats). More likely deficiencies are in certain micronutrients (as indicated above). Foods containing nutrients of particular concern to SCI are listed in Table 4 .

| Nutrient | Examples of Nutrient Containing Foods |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A | Liver, fish oil, broccoli, spinach, romaine, collard, turnip, mustard greens, squash, pumpkin, carrot, sweet potatoes, mango |

| Vitamin D a | Salmon, tuna, and mackerel (small amounts also in beef liver, cheese, egg yolks) Dietary supplement fact sheet: vitamin D |

| Vitamin E | Nuts, seeds, vegetable oils, spinach, romaine, collard, turnip, and mustard greens |

| Vitamin C | Citrus fruits, tomatoes, potatoes, red and green peppers, kiwifruit, broccoli, strawberries, brussel sprouts, and cantaloupe |

| Biotin | Brewer’s yeast; cooked eggs, especially egg yolk; sardines; nuts (almonds, peanuts, pecans, walnuts) and nut butters; soybeans; other legumes (beans, black eyed peas); whole grains; cauliflower; bananas; and mushrooms |

| Vitamin B5 | Meat, vegetables, cereal grains, legumes, eggs, and milk |

Excess intake of macronutrients is common for persons with SCI and should be reduced ideally through reduction of intake of those foods listed in Table 2 . In addition, salt intake by persons with SCI generally exceeds recommended levels. These levels are established for the general population because of the positive relation of salt intake with high blood pressure. However, persons with SCI at T6 and above where sympathetic nervous system (SNS) control is likely compromised frequently suffer from hypotension. Therefore, increased salt intake particularly in the morning has been recommended for individuals suffering from hypotension. In contrast, person with SCI but uncompromised SNS should reduce their salt intake in line with general guidelines (<2300 or 1500 mg/d based on age, ethnicity and disease status).

Recommended diets

Dietary recommendations for persons with SCI are usually in line with those adopted for the general population with exceptions for energy intake and sodium targets, as outlined above. Two contemporary dietary strategies that have been proven to positively affect components of the CMS are Mediterranean-style diets and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), which are summarized in Fig. 2 .

Exercise component of TLI

Based on (1) The World Health Organizations’ Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health ; (2) The US Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans ; (3) The Exercise is Medicine’s Health Care Providers’ Action Guide ; and (4) SCI Action Canada.

- •

Exercise absent caloric restriction is unlikely to induce weight loss.

- •

Exercise recommendations for adults with SCI to improve cardiometabolic risk factors are the same as for adults without disabilities.

- •

To improve health and wellness, persons with SCI should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic exercise each week, perform strength training exercises at least 2 times a week, and stretch at least 2 times a week.

Key points

- •

Exercise Considerations—Role in Health and Weight Management

Exercise interventions should be applied with the primary objective of improving metabolic profiles and body composition (not mere weight loss per se). Nevertheless, exercise/PA interventions can augment caloric restriction to accelerate/maintain weight loss. However, as explained in discussion below, for most persons with SCI exercise as a monotherapy will be insufficient to induce weight loss. Although exercise interventions in isolation are unlikely to achieve weight loss for persons with SCI, they are effective for improving strength, which in turn support daily independence. Strength gains are also typically associated with an underlying muscle gain and hence positive body composition changes. Over time, increased muscle mass could enhance resting metabolic rate and thus support TEE and weight management.

Exercise and Caloric Balance

Weight loss is achieved through a sustained negative caloric balance as described in the diet component above. Because of lower absolute peak aerobic levels, reduced muscle mass available to expend calories, and autonomic dysfunction (above T6), persons with SCI burn 30% to 50% fewer calories than non-disabled persons during moderate to vigorous exercise intensities. This decreased caloric capacity to burn calories requires increased exercise duration to achieve similar caloric expenditures. Given most non-disabled individuals are challenged to achieve the total weekly recommended PA amounts required to lose weight (60–90 min a day, 5 times a week), it is reasonable to assume the additional time required by persons with SCI (78–135 min a day, 5 times a week) to reach similar caloric expenditures will present an insurmountable obstacle for many. In addition, performing common modes of exercise for SCI such as pushing a wheelchair or using arm ergometry for extended periods of time may also increase the risk for shoulder and wrist overuse injury.

PA Requirements for Weight Loss, Health, and Wellness

The PA levels required for weight loss are much greater than those required to support health and wellness gains (ie, improved cardiometabolic risk factors). Nevertheless, the amount required to support health and wellness in persons with SCI is the same as required for the general population. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Department of Health and Human Services state that guidelines for adults without disabilities can be valid for adults with disabilities. Both organizations note that adjustments can be made as needed to accommodate each individual’s exercise capacity, health risks, or limitations. In as much as possible, people with SCI should be encouraged to achieve the minimum targets ( Table 5 ).

| Aerobic PA | |||

| Intensity a | Moderate | Vigorous | |

| Weekly total a | ≥150 min Can be accumulated in bouts ≥10 min (eg, 30 min 5 d a wk) (eg, 15 min morning and evening 5 d a wk) | OR | ≥75 min Can be accumulated in bouts ≥10 min (eg, 15 min 5 d a wk) (eg, ∼11 min every day of the week) |

| Activity type | Any activity that achieves the above | Any activity that achieves the above | |

| Lay intensity guide b | “Somewhat hard,” “you can talk but not sing,” or is 5 or 6 on a 0 to 10 scale | “Really hard,” “you can’t say more than a few words without pausing for breath,” or is 7 or 8 on a 0 to 10 scale | |

| AND | |||

| Resistance training | |||

| Frequency a | ≥2 d per wk | ||

| Number of exercises | All major muscle groups a (∼4–5 upper body exercises). (For shoulder health, be sure to include scapular stabilizer and posterior shoulder muscles.) | ||

| Sets and repetitions a | 3 sets of 8–12 repetitions (each exercise) | ||

| Weight b | Enough to create a feeling of “quite challenged” at the end of each set | ||

| AND | |||

| Upper extremity stretching | |||

| Frequency c | 2–3 d per wk | ||

| Areas to stretch c | Chest and anterior shoulders & perform full range of motion for all upper extremity joints | ||

| When stretching c | Apply a gentle, prolonged stretch to each area of tightness | ||

a WHO PA recommendation for adults ages 18–64.

b Lay Intensity Guide from SCIAction Canada.

c Stretching guideline from Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine’s Upper Extremity Preservation Guideline.

Exercise Prescription

PA guidelines have been established to be easily comprehensible by the general population but implementation and adherence are greatly enhanced with health care provider guidance. When physician advice is coupled with an exercise plan, patients are 2 times more likely to exercise than those who receive advice but no exercise plan. This increases to 3 times more likely to exercise when physician advice is coupled with an exercise plan and regular follow-up queries. Persons with SCI indicate a preference for obtaining PA information from their health care provider. Thus, there is a strong potential that SCI health care providers can increase the PA level of their patients by providing exercise prescriptions.

A Health Care Providers Action Guide from the Exercise is Medicine (EIM) initiative is available online. This initiative is a joint effort by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Medical Association “to make physical activity and exercise a standard part of a global disease prevention and medical treatment.” It is widely supported by professional societies, including the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPMR), American Physical Therapy Association, American Heart Association (AHA), and the American Osteopathic Association. The Health Care Providers guide is available on the EIM Web site. The guide contains a 4-step PA prescription process, which should be adjusted for SCI as outlined in Box 2 .

Step

- 1.

If patient is not currently exercising and unwilling to start an exercise program, advise of risks of inactivity (eg, loss of independence, weight gain) and encourage them to exercise.

- i.

Recent SCI-specific research indicates loss-framed messages (eg, inactivity risks) result in greater increases in PA than gain-framed messages (eg, PA benefits).

- i.

- 2.

Administer Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire Plus (PAR-Q+), which includes SCI-specific clearance questions/concerns.

- 3.

No SCI-specific adaptation necessary.

- 4.

In addition to aerobic and strength training, recommend a stretching component to help protect the shoulders from overuse. Table 5 presents all components of an exercise prescription.

- 1.

Specific Considerations for SCI

A “complete” exercise prescription includes aerobic and strength training. In addition, regular flexibility exercise (ie, stretching) should be encouraged to help protect the shoulders from overuse. Table 5 presents all components of an exercise prescription.

Aerobic exercise considerations

To support health and wellness, the WHO recommends adults aged 18 to 65 perform at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic PA each week, translating to 30 minutes of moderate intensity or 15 minutes of vigorous intensity activity 5 days a week. Aerobic activity can be accumulated in bouts as short as 10 minutes. For a person with SCI, moderate intensity is described as “somewhat hard,” “you can talk but not sing,” or is 5 or 6 on a 0 to 10 scale. Vigorous intensity is described as “really hard,” “you can’t say more than a few words without pausing for breath,” or is 7 or 8 on a 0 to 10 scale.

Muscle strengthening considerations

In addition, WHO recommends muscle strengthening activities involving major muscle groups be done 2 or more days a week. For persons with SCI, the specific recommendation is at least 3 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions for each major muscle group 2 times a week. The weight should be enough to create a feeling of “quite challenged” at the end of each set. For most persons with SCI, 4 to 5 different upper extremity exercises should be sufficient to address all upper extremity muscles. It is very important to ensure scapular stabilizers and posterior shoulder muscles are strengthened to protect the shoulder against overuse injuries.

Stretching considerations

In conjunction with strengthening the scapular stabilizers and posterior shoulder muscles, it is critical that persons with SCI stretch their chest (pectoralis muscles) and anterior shoulders (long head of the biceps). The Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend that persons with SCI should stretch 2 to 3 times a week. During each stretching session, they should apply a gentle, prolonged stretch to each area of tightness in the neck, upper trunk, and each arm. In addition, during each stretching session they should perform full range-of-motion exercises for all upper extremity joints.

Referral to a Clinical Exercise Professional

In lieu of or in conjunction with writing an exercise prescription, a health care provider can refer their patient to a clinical exercise professional. Examples of clinical exercise professionals include ACSM-certified clinical exercise specialists and ACSM-registered exercise physiologists. The EIM initiative suggests health care professionals develop a local network of clinical exercise professionals to whom they can refer their patients. By developing a local network, health care providers can ensure local clinical exercise professionals are well versed in the needs, limitations, and health risks of persons with SCI. Alternatively, a local clinical exercise professional can be found by searching the ACSM ProFinder information database.

Managing Shoulder Pain

Upper limb injury is a serious concern for persons undertaking upper extremity exercise, as the prevalence of shoulder pain and injury is 30% to 60% after SCI. If shoulder pain is present, circuit training and anterior stretching/posterior strengthening regimens are effective treatment options. The exercise prescription can be tailored as needed to minimize pain and injury until more intense exercise is tolerated. This approach is consistent with recommendations for comprehensive upper limb preservation from the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine.

Behavioral component of TLI

Adapted from the joint American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA task force and intended to reflect the behavior modification therapy of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Modified for SCI where applicable.

- •

A comprehensive TLI for CMS risk includes structured behavior modification therapy.

- •

Key behavioral outcome objectives include

- 1.

Education/instruction on diet and exercise components and role in lowering CVD risk

- 2.

Self-monitoring of body weight, caloric intake, and PA levels, and

- 3.

Understanding psychosocial barriers and developing cognitive strategies to overcome barriers to diet and exercise goals.

- 1.

Key points

- •

Behavioral Modification

Evidence of current CMS prevention guidelines has been set forth by the ACC/AHA and consists of a collective series of documents outlining the assessment, treatment, and management of CMS risk factors, with particular attention to blood cholesterol, overweight, and obesity. Specifically, within the content of the overweight and obesity guidelines, it states that one of the principle components of an “effective high-intensity…lifestyle intervention” is the “use of behavioral strategies to facilitate adherence” to weight management recommendations. It is asserted that this therapy should provide a “structured behavioral change program.” As a part of a comprehensive TLI, comprised of diet, PA, and behavior therapy, there is a “high-to-moderate” strength of evidence (derived from randomized control trials, meta-analysis, and quality observational studies) for efficacy in facilitating weight loss, when compared with “usual,” “minimal” care, or no-treatment in the short term (6 months), intermediate (6–12 months), or long term (>1 year).

Key aspects

Several behavioral intervention aspects influence the overall effectiveness of a comprehensive TLI and include frequency and duration of treatment, individual versus group sessions, and onsite versus telephone/e-mail contact. The key behavioral outcome objectives summarized by the ACC/AHA are also outlined extensively in the landmark DPP behavioral program and include: (a) instruction on components of weight management (diet and exercise) and role in lowering CVD risk factors; (b) continuous “self-monitoring” with respect to body weight, food intake and composition, and PA level; and (c) cognitive restructuring and developing strategies to overcome psychosocial barriers to program compliance. Data from the DPP report both significant weight loss and a 58% decrease in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus following a structured TLI, consisting of nutrition, exercise, and behavioral weight management. Importantly, the DPP target, greater than or equal to 7% weight loss, was successful in maintaining low-diabetes-rate onset, as reported in a separately designed DPP outcome study (median follow-up of 5.7 years), demonstrating effective long-term lifestyle change and cardiometabolic health benefit.

Several major CVD risk factors, including overweight/obesity, are established as pervasive in chronic SCI. Research outlining the impaired psychosocial health, quality of life, and subjective well-being following SCI is extensive (reviewed in Ref. ) and, correspondingly, emerging research supports the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (reviewed in Ref. ) in improving health-related quality of life and psychological issues. Although the scope of behavior therapy reviewed was in relation to depression, anxiety, coping, and adjustment post-SCI, it illustrates the potential effectiveness of directed behavior change on secondary complications in SCI.

Recent developments

More recent reports, including the authors’ group, have focused on barriers to exercise participation and factors influencing dietary status and nutritional habits, addressing physical and environmental challenges, and inadequacies in education and psychosocial support, as relevant contributors to these imprudent lifestyle choices, which promote CVD and overweight/obesity risk. As such, a directed cognitive behavioral program as a component of management guidelines for a comprehensive population-specific lifestyle intervention is greatly in need. To our knowledge, there has been one recent uncontrolled study administering dietary and exercise “advice” given in 3 “behavioral change” consultations over 3 months, and reporting weight loss and reduced BMI. Still, there remain no comprehensive reports of directed intervention trials for obesity and CMS risk factors in SCI. Currently underway, our group is conducting a TLI trial for cardiometabolic disease prevention/treatment in the SCI population. The TLI integrates dietary recommendations, exercise prescription, and structured behavioral therapy, consisting of a 16-session educational program modified from DPP principles to address the specific needs of persons with SCI ( Table 6 ). Preliminary data confirm the effectiveness of the TLI in significantly reducing major CVD risk factors, including body weight, BMI, plasma lipid profile, and glycemic markers. These results highlight the potential effectiveness of a TLI for cardiometabolic disease in SCI.