Abstract

Objective

A systematic review of the literature to determine whether in patients with neurological heterotopic ossification (NHO) after traumatic brain injury, the extent of the neurological sequelae, the timing of surgery and the extent of the initial NHO affect the risk of NHO recurrence.

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed and Cochrane library for articles published up to June 2015. Results were compared with epidemiological studies using data from the BANKHO database of 357 patients with central nervous system (CNS) lesions who underwent 539 interventions for troublesome HO.

Results

A large number of studies were published in the 1980s and 1990s, most showing poor quality despite being performed by experienced surgical teams. Accordingly, results were contradictory and practices heterogeneous. Results with the BANKHO data showed troublesome NHO recurrence not associated with aetiology, sex, age at time of CNS lesion, multisite HO, or “early” surgery (before 6 months). Equally, recurrence was not associated with neurological sequelae or disease extent around the joint.

Conclusions

The recurrence of NHO is not affected by delayed surgery, neurological sequelae or disease extent around the joint. Surgical excision of NHO should be performed as soon as comorbid factors are under control and the NHO is sufficiently constituted for excision.

1

Introduction

Although patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) mainly show medium and long-term cognitive and behavioral disorders , motor and orthopedic sequelae may be involved in the difficulties they face. Neurogenic heterotopic ossification (NHO) occurs in 4% to 23% of patients after TBI , and for approximately 45% of patients with NHO, the disease occurs in 2 or more locations . The disease involves the growth of bony tissue around joints. This growth can be painful and may also have functional consequences because it can limit joint range of motion. The timing of NHO occurrence after TBI varies greatly, from 2 to 3 months or more. This discrepancy in occurrence is mainly due to difficulties in diagnosing the condition . The mechanisms causing NHO are still poorly understood.

Attempts have been made to develop prophylactic treatments for NHO. Studies of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) provide strong support for the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) ; however, their use is limited by their side effects . Currently, the only treatment for NHO is surgical excision, and management of the condition lacks guidelines . Surgical excision is effective for increasing range of motion and importantly, improving both active and passive (e.g., access to the perineum or axilla for hygiene) function , reducing pain (i.e., nerve decompression) and ameliorating bedsores .

Unfortunately, about 20% of patients (from 17 to 58% ) show recurrence of symptomatic NHO, with renewed pain and loss of range of motion and function. Empirical beliefs regarding the causes of recurrence have led to the development of certain clinical practices for treating NHO . For example, many surgeons prefer to wait until the NHO is mature before excision even though prolonging surgery may lead to a cascade of negative events: risk of ankylosis, intra-articular lesions, bone loss in the femoral head and increased risk of fracture during or after surgery . The severity of the neurological injury and the extent of the initial NHO is thought to affect recurrence .

Our centre follows many patients with NHO and we have developed a database, “BANKHO,” containing data for patients who have undergone surgery for troublesome NHO after CNS lesions . This database was started in 1993 and was used for a 2009 epidemiological study addressing 3 issues in patients with different types of CNS lesions : the extent of the neurological sequelae, timing of surgery and extent of the initial NHO associated with the risk of NHO recurrence. At that time, the database contained data for 357 patients, including 539 first-time interventions for NHO (129 for multiple sites). All the surgical interventions in the database were performed by the same surgeon (PD). The results showed that most HO requiring surgery occurred after TBI (199 patients [55.7%]; 304 surgeries [56.4%]). The hip was the primary site of HO (163/304 [53.6%]), followed by the elbow (85/304 [28.0%]), knee (43/304 [14.1%]) and shoulder (13/304 [4.3%]); 16 cases (5.6% [16/304]; 16 patients) showed recurrence requiring further surgery.

We aimed to use the BANKHO database and literature data to investigate the validity of the beliefs relating to the post-excision risk of recurrence of NHO. Three questions were posed: Is there a relationship between the:

- •

timing of the excision;

- •

severity of the neurological sequelae;

- •

and extent of the initial NHO and risk of recurrence?

2

Materials and methods

2.1

Systematic literature search

We performed a systematic review of the literature following the PRISMA recommendations ( www.prisma-statement.org ), searching for articles published up to June 2015 in English or French with an available abstract in MEDLINE via PubMed and Cochrane Library databases with the MeSH headings “head injury”, “traumatic head injury”, “heterotopic ossification” and “surgery.” The titles and abstracts of the studies retrieved were screened to select those reporting on the timing of HO excision and recurrence in patients with TBI (excluding spinal cord injury, stroke, orthopaedic conditions, total hip arthroplasty and burns). The full texts of the selected studies were independently screened by 2 authors (F.G. and A.S.) for eligibility. From data yielded by the literature and advice from all authors, the level of evidence of the proposed recommendations was graded according to the health authority in France ( Table 2 ).

Studies were classified as published before 2002 or 2002 and later. Studies published in 2002 and later were considered to evaluate current practices, avoiding the confounding factor of changes in clinical practice. Moreover, during the beginning of the 2000s, articles providing other points of view concerning the 3 questions were published. Studies before 2002 were considered to evaluate previous practices. Any reviews discussing surgery for NHO, timing of surgery and recurrence risk were selected to investigate changes in clinical practice and recommendations.

2.2

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies had to include patients with TBI who underwent surgery for troublesome HO. They had to state the aetiology of the neurological lesion, time from diagnosis to surgery, any post-surgical complications and any recurrence of HO, with the timing of the recurrence. Patients had to be followed up for at least 3 months. To answer question 2 (effect of the severity of the neurological sequelae on recurrence risk), studies also had to report the functional and/or cognitive status of patients before surgery. To answer question 3 (effect of the extent of the NHO on recurrence risk), studies also had to report the results of imaging (X-ray and/or CT scan) and the clinical assessment.

2

Materials and methods

2.1

Systematic literature search

We performed a systematic review of the literature following the PRISMA recommendations ( www.prisma-statement.org ), searching for articles published up to June 2015 in English or French with an available abstract in MEDLINE via PubMed and Cochrane Library databases with the MeSH headings “head injury”, “traumatic head injury”, “heterotopic ossification” and “surgery.” The titles and abstracts of the studies retrieved were screened to select those reporting on the timing of HO excision and recurrence in patients with TBI (excluding spinal cord injury, stroke, orthopaedic conditions, total hip arthroplasty and burns). The full texts of the selected studies were independently screened by 2 authors (F.G. and A.S.) for eligibility. From data yielded by the literature and advice from all authors, the level of evidence of the proposed recommendations was graded according to the health authority in France ( Table 2 ).

Studies were classified as published before 2002 or 2002 and later. Studies published in 2002 and later were considered to evaluate current practices, avoiding the confounding factor of changes in clinical practice. Moreover, during the beginning of the 2000s, articles providing other points of view concerning the 3 questions were published. Studies before 2002 were considered to evaluate previous practices. Any reviews discussing surgery for NHO, timing of surgery and recurrence risk were selected to investigate changes in clinical practice and recommendations.

2.2

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies had to include patients with TBI who underwent surgery for troublesome HO. They had to state the aetiology of the neurological lesion, time from diagnosis to surgery, any post-surgical complications and any recurrence of HO, with the timing of the recurrence. Patients had to be followed up for at least 3 months. To answer question 2 (effect of the severity of the neurological sequelae on recurrence risk), studies also had to report the functional and/or cognitive status of patients before surgery. To answer question 3 (effect of the extent of the NHO on recurrence risk), studies also had to report the results of imaging (X-ray and/or CT scan) and the clinical assessment.

3

Results

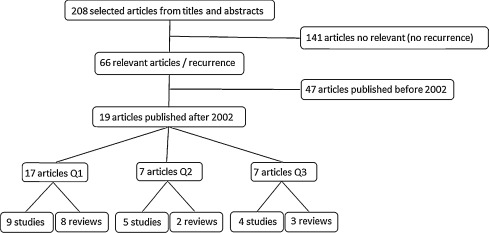

We identified 208 reports of studies; 67 were included. Overall, 19 articles were published between January 2002 and June 2015 ( Fig. 1 and Table 1 [studies only]): 17 on the relationship between the timing of excision and risk of recurrence (8 reviews and 10 studies ); 7 on the relationship between the severity of the neurological sequelae and risk of recurrence (2 reviews and 5 studies ); and 7 on the relationship between the extent of the initial NHO and risk of recurrence (3 reviews and 4 studies ).

| Author | Year | No. of patients | No. of NHOs | Location (joint) | Design | Mean follow-up (range) (months) | Rate of recurrence | Additional procedure | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Level of evidence a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Palma | 2002 | 10 | 14 | Elbow | Retrospective | 23 (12–34) | 0/14 | Yes | Yes | N/A | C | |

| Melamed | 2002 | 9 | 12 | Hip, knee, elbow | Prospective | 18 (9–50) | 0/12 | No | No | N/A | C | |

| Fuller | 2005 | 17 | 22 | Knee | Retrospective | 32 (10–98) | 0/17 | Etidronate (all) Radiation (2) | No | N/A | N/A | C |

| Sorriaux | 2005 | 44 | 51 | Elbow | Retrospective | 45 (6–48) | 2/51 | No | No | N/A | C | |

| Carlier | 2005 | 29 | 45 | Hip | Prospective | 45.5 (8–24) | 2/45 | No | N/A | N/A | C | |

| Genet | 2011 | 357 | 539 | Hip, knee, shoulder, elbow | Cohort study (both prospective and retrospective) | 6.9 (5.7–19.4) | 31/539 | NSAID (All) Radiation (rare) | No | N/A | N/A | B |

| Genet | 2011 | 95 | 95 | Hip | Retrospective (case–control study) | 10.3 (0.7–159.4) | 19 | NSAID (All) Radiation (rare) | N/A | N/A | No | C |

| Mavrogenis | 2012 | 24 | 33 | Hip | Retrospective | 30 (12–96) | 7/33 | NSAID (All) Radiation (All) | N/A | N/A | No | C |

| Genet | 2012 | 80 | 80 | Hip, elbow | Retrospective (case–control study) | 15.5 (2.7–78.5) | 16 | NSAID (All) Radiation (rare) | No | No | N/A | C |

3.1

Level of evidence of included studies

The level of evidence of studies was generally poor ( Tables 1 and 2 ). All studies were graded C except one that was graded B because it was a cohort study with a large number of surgeries . Most of the other studies were retrospective. Two studies were prospective, with a lower level of evidence (no randomization, non-comparative). There were no randomized control trials and scales used were frequently not validated for this purpose mainly because the diagnosis of NHO is always delayed relative to its occurrence, the incidence is relatively low, sample sizes are small, and pathogenesis is still poorly understood, so early diagnosis is difficult. For this reason, we decided to keep all the studies selected by our process .

| Grade | |

|---|---|

| A | Validated scientific evidence: based on studies with a high level of evidence: randomized controlled vs. placebo clinical trials with high statistical power and without major bias or meta-analysis of randomized comparative clinical trials, decision analysis based on well-conducted studies |

| B | Scientific presumption: based on scientific presumption using studies with intermediate level of evidence, such as randomized comparative trials with low statistical power, well-conducted non-randomized comparative trials, cohort studies |

| C | Low level of scientific evidence: based on studies with a lower level of evidence, such as case studies, retrospective studies, series of cases, comparative studies with major biases |

| AE | Scientific expert agreement: in the absence of studies, recommendations have been based on experts’ opinions resulting from a workgroup, after having consulted a reading group. The absence of level of evidence grade does not mean that the recommendations are not relevant and useful. It must, however, encourage teams to conduct further studies |

3.2

Report of the literature

3.2.1

Relationship between the timing of excision and risk of recurrence

3.2.1.1

Historical background

During the 1990s, following the experience and publications of Garland et al., several teams agreed to wait for at least the arbitrary 18 months after TBI before considering surgery , mainly to ensure that maximal neurological recovery had occurred if the aim of surgery was to improve function, as well as to avoid recurrence (by ensuring NHO maturity). This delay could be shortened in cases of rapid neurological recovery .

3.2.1.2

Since 2002

It is currently widely accepted that to reduce the risk of recurrence, the NHO must reach maturity before surgery . However, some studies suggest that this is not the case and that surgery can be carried out before 12 months to reduce postoperative stiffness . A major problem is the difficulty in determining when the NHO reaches maturity . Several methods have been tested (radiography, CT scan, biological investigations, three-phase bone scan, etc. ) with controversial results and samples that were often heterogeneous after SCI and TBI . Moreover, these studies frequently lacked statistical analysis. In 2007, Chalidis et al. performed a meta-analysis of 16 studies (255 patients) and could not establish a relationship between timing of surgery and recurrence of NHO because of methodological limitations in the studies, including variability between surgical procedures and surgeon experience, non-standardized post-surgical management, variability of patient data files, lack of consistency within the datasets themselves, and huge differences in the timing of surgery ranging from 13 to 30 months after TBI. The rate of recurrence was estimated at about 19.8% (95% confidence interval 14.4–26.1%), but the outcome measures used (new decrease in range of motion, ankylosis, radiographic recurrence, etc.) were disparate. Shehab et al. discussed the surgeon’s predicament: waiting for NHO maturity to avoid recurrence exposes the patient to prolonged pain and loss of joint motion, which both may reduce functional ability and probably neurological recovery as well as increase the risk of postoperative complications such as hematoma or fracture . Unfortunately, most studies reported disparate rates of NHO recurrence (from 0 to 92% radiographic recurrence) whatever the timing of surgery (less or more than 18 months after the CNS lesion) . One point from these studies is that even if the timing of surgery and follow-up are heterogeneous, radiographic recurrence (without symptoms) is largely more frequent than clinical recurrence (with symptoms) and whether the timing of surgery has an impact on clinical recurrence is not clear. Some studies did not report enough information regarding the timing of surgery or the rate of recurrence .

3.2.1.3

BANKHO database

There were no recurrence of NHO following the surgical interventions performed during the first year after CNS damage. After 1 year, when recurrence occurred, it was not associated with aetiology, sex, age at time of CNS lesion, multisite NHO, or “early” surgery (before 6 months) .

3.2.2

Relationship between severity of the neurological sequelae and risk of recurrence

3.2.2.1

Historical background

The second factor suspected to increase the risk of recurrence was the severity of the neurological sequelae. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was considered that the more severe the residual deficit (cognitive and motor), the worse the functional outcome of surgery and the greater the risk of recurrence . In 1985, one surgical team experienced in NHO proposed a subjective clinical scale to evaluate residual cognitive and functional deficits relating to the brain injury (Garland status or Rancho Los Amigos status: Class I–minimum cognitive deficits with minimum physical disability, Class II–minimum cognitive deficits with moderate physical deficits, Class III–minimum cognitive deficits with severe physical deficits, Class IV–moderate to severe cognitive deficits with minimum to moderate physical disability, and Class V–moderate to severe cognitive deficits with severe physical disability), specifically for decision making in NHO management . The scale is still widely used for decisions relating to the appropriateness of surgical excision of NHO and notably to predict the functional results of the surgery as well as the risk of recurrence .

3.2.2.2

Since 2002

Only a few studies have evaluated the association between functional/cognitive status or relative gain in range of motion and recurrence . They found, using the Garland status, better motor recovery and improvements in range of motion for patients with few neurological sequelae. Some studies did not find a greater risk of recurrence, but the samples were small . Conversely, significant functional improvements after surgery have been reported, even in patients with severe impairment . The authors of this latter study suggested that NHO excision should be envisaged as soon as possible to optimize recovery and quality of life.

3.2.2.3

BANKHO database

A retrospective case–control study included patients with troublesome HO requiring surgery after TBI with (case, n = 16) or without recurrence (control, n = 64). Each patient with HO recurrence was matched with 4 patients without recurrence after 6 months of follow-up (control patients) by sex, pathology (TBI), surgical indications for HO and age at the time of surgery (± 4 years). The authors found no significant relationship between recurrence and timing of surgery, even after including all matching factors and Garland status in the regression model. No association was found between the severity of the neurological sequelae (Garland status) and risk of NHO recurrence after TBI.

3.2.3

Relationship between the extent of the initial NHO and risk of recurrence

3.2.3.1

Historical background

The last factor believed to have an impact on the recurrence of troublesome NHO after CNS lesion is the extent and the number of NHOs. The most commonly used classification is by Brooker, who developed a method in 1973 to classify the degree of ectopic bone formation around the hip after total hip arthroplasty . This classification is useful in that it can be based on a single anteroposterior X-ray of the hip (Class I–island of bone within the soft tissues about the hip, Class II–bone spurs from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur leaving at least 1 cm between opposing bone surfaces, Class III–bone spurs from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur, reducing the space between opposing bone surfaces to < 1 cm, Class IV–apparent bone ankylosis of the hip). This rating was correlated with global hip function . With SCI with this classification, the extent of the initial NHO was suggested to be able to predict postoperative recurrence . Consequently, experienced teams considered that Brooker’s classification should be systematically used in patients with CNS lesions, although based on a study with no statistical analysis. Garland et al. noted a possible association between risk of recurrence and radiographic grade (maturity and extent) of the NHO in SCI patients . The authors also found an association between the risk of recurrence and number of NHOs (≥ 3) in another study of TBI patients . A few years later, a study by Ebinger et al. found no association between risk of recurrence and preoperative Brooker status .

3.2.3.2

Since 2002

Consensus is lacking for radiographic classification of NHO . Several teams have tried to find a link between the risk of recurrence and the preoperative extent of the NHO; however, results were based on clinical observations and therefore were only descriptive . The Brooker classification remains the most widely used, although its validity has never been evaluated in patients with neurological disorders or in joints other than the hip . A disadvantage of the scale, as highlighted by Mavrogenis et al., is that it does not indicate in which anatomical compartment the HO is situated . Consequently, there is no correlation between the score and the extent of the HO in each compartment, so boundaries cannot be determined. Equally, the classification does not help the surgeon determine the surgical approach and the prognosis. Moreover, similar to orthopedic-related HO , the Brooker scale gave pessimistic expectations of hip range of motion. Indeed, hip HOs classified as Brooker scale III or IV were not clinically ankylosed .

3.2.3.3

BANKHO database

A case–control study using the BANKHO database found no significant relationship between recurrence and extent of NHO around the joint or Brooker status, even when all matching factors were included in the analysis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree