Quality Improvement and Reporting in Electrodiagnostic Medicine

William S. Pease

What is Quality?

Physicians and healthcare institutions are expected to put their best efforts into improving quality of care and minimizing the risks to the patient. The latter concept dates to Hippocrates, and the former is almost as old in its relationship to the lifelong learning that is the basis for professional work. Now it is common to find quality-related healthcare data on the Internet and in the press. For example, the Leapfrog Group (http://www.leapfroggroup.org) and many other institutions are insisting upon improvements in healthcare quality and safety.

While some aspects of quality are considered subjective or individual, there is consensus in the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO, commonly pronounced “Jayco”) approach, whose goals are to increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes. A quality improvement (QI) program should address all processes of care that affect the patient and other stakeholders in the EMG evaluation program (1). The first steps in developing a QI program are to assign responsibility, ensure accountability, and support delegation of authority as appropriate (2). One must then systematically examine the quality of care that is provided. This must always be viewed as a continuous process of managing and improving the patient care in each facility. The scopes of care for the area must be delineated and the key functions in the area identified that are likely to have the greatest impact on the patient. Measurable indicators are developed and a data-monitoring system is created so that information can be shared with the group and with the interested stakeholders. The data serve as feedback in the system to trigger improvements in the processes and also to monitor the outcome of the changes. Actions may be directed toward achieving outcomes above a certain target created internally or related to an external benchmark.

An important overall indicator of quality is patient satisfaction. It is also important to assess the satisfaction of physicians and agencies that refer patients and use the reports in their reviews. Some examples of quality indicators used to measure patient satisfaction include the following:

Were the services performed on a timely basis?

Was the staff courteous and professional?

Is the office area safe and accessible?

Did the physician communicate well before and after the procedures?

Data on patient satisfaction can be collected either in the office at departure or (more commonly) by mail survey sent to an adequate sample, typically 20% of the patients. Surveying for quality purposes is not considered scientific medical research and does not require research ethics or institutional review board (IRB) review and approval.

In internal peer review of EMG reports, several factors might be considered, such as the following:

Appropriate clinical information was included.

Correct nerves and muscles were studied in relation to the presenting and final diagnoses.

There is internal consistency of the data that suggests accuracy in measurement.

A rational discussion, impression, and recommendation section is included that provides useful information to the referring physician.

Peer review is strongly encouraged as part of the QI process, with a review of 10 reports per quarter from each physician.

Qualifications of the Electrodiagnostic Medical Consultant

The overall responsibility for the testing in an electrodiagnostic medicine (or EMG) laboratory should be assigned to a physician medical director who has appropriate board certification in the field and who also keeps abreast of the field through continuing education (3,4). Education and training in electrodiagnostic medicine occurs within the framework of residency in physical medicine and rehabilitation, as well as most neurology programs in the United States and Canada. Consensus guidelines for education followed by both specialties have been developed by the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM, formerly AAEM). The educational requirements include broad knowledge of neuromuscular diseases and injuries, as well as the performance of at least 200 patient EMG evaluations as a trainee. Some physicians also pursue subspecialty fellowship training in EMG after residency. Certification of competence in electrodiagnosis is included in certification of the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. The American Board of Electrodiagnostic Medicine (ABEM) has a testing and certification program operated in a relationship with the AANEM that is highly regarded. The ABEM examination requires at least 1 year of experience after training and the performance of an additional 200 examinations for eligibility. EMG competence is also a component of the training and testing in the subspecialties of Clinical Neurophysiology and Neuromuscular Medicine (new in 2005), which are under the auspices of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. All of these certifying programs include maintenance of certification programs of continuing education and periodic retesting.

Staff of the EMG laboratory may include technicians who assist the electrodiagnostic medicine physicians and who also perform nerve conduction studies under the direct supervision of the medical staff. The American Association of Electrodiagnostic Technologists has developed training guidelines and a board-certification process for the technicians.

The Electrodiagnostic Medical Consultation

The EMG evaluation is an extension of the physical examination of the patient, using electronic amplifiers to extend our sensory ability into the realm of “perceiving” the action potentials of nerves and muscles. The consultant uses the electrophysiologic methods to diagnose, evaluate the severity of, and manage the treatment of patients with neuromuscular problems.

Evaluation of possible proximal nerve injury affecting a limb usually begins with a clinical evaluation suggesting nerve root or plexus injury. Needle EMG examination is recommended as the test modality with the best sensitivity and specificity for these diagnoses (5,6). Selection of the appropriate muscles to be tested is based upon the roots or nerves thought most likely to be affected based upon the clinical evaluation (7), as well as the patient’s tolerance and the examiner’s abilities and training. The muscle selections later in the study are also guided by any abnormal findings that are seen. In general, a screening examination is used when the patient’s presentation does not limit the possibilities. This screening examination of five or six muscles (5,6) is designed so that each root and plexus component is evaluated based upon the usual innervation patterns (myotomes). As abnormalities are identified, additional muscles are selected to confirm that an injury exists and that other neural components are not affected in the same

anatomic region. This approach is referred to as “surrounding the focal abnormality with a ring of normal findings.” When the screening examination produces no abnormalities (a situation we physicians paradoxically refer to as “negative”), then the differential diagnosis is refined, and this might lead to alternate testing. The classic abnormalities described in the pathologic states discussed in other chapters are usually found in muscles with mild to moderate weakness.

anatomic region. This approach is referred to as “surrounding the focal abnormality with a ring of normal findings.” When the screening examination produces no abnormalities (a situation we physicians paradoxically refer to as “negative”), then the differential diagnosis is refined, and this might lead to alternate testing. The classic abnormalities described in the pathologic states discussed in other chapters are usually found in muscles with mild to moderate weakness.

For patients suspected of having peripheral nerve dysfunction such as polyneuropathy or entrapment, the EMG laboratory evaluation usually begins with sensory and motor nerve conduction studies. The specific nerves tested and possible addition of F waves to the studies depends upon the diagnoses under consideration (8), as discussed in detail in other chapters of this text. Appropriate selection of nerves and stimulation sites will allow identification of distal, proximal, or segmental slowing, as well as identifying reduced amplitude or conduction block. All of these parameters are necessary for the appropriate analysis of the patient’s diagnosis, severity, and prognosis (8). Diagnostic information is most likely to result from testing areas that are moderately affected, resulting in measurable but markedly abnormal electrical recordings.

Safety

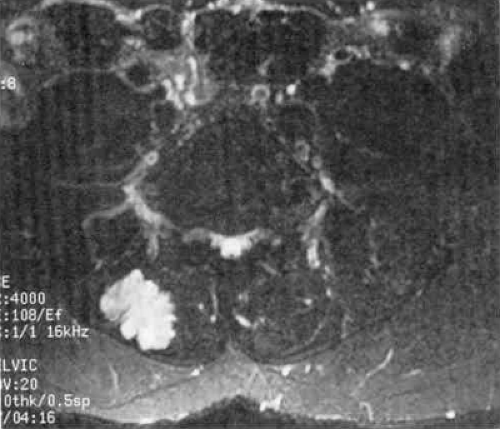

Patient safety in the EMG laboratory involves risks of infection, bleeding, electrical injury, and penetration of the chest or abdomen (9). Infection is managed by the use of universal precaution standards, including barriers such as gloves and disinfection, as well as through the use of disposable supplies. Hemorrhage (Fig. 7-1) is reported rarely but can occur even in the patient without coagulopathy. The physician should not perform needle EMG studies in patients at a high risk of bleeding, such as those with poorly controlled coagulopathy or INR values above the therapeutic range. The patient on appropriate levels of therapeutic anticoagulants can be safely studied with added pressure for hemostasis being applied at the needle site after withdrawal. In the case illustrated in Figure 7-1, the examiner reports using concentric EMG needles (0.46 mm in diameter) and asked the patient to activate the paraspinal muscles for evaluation of motor unit potentials (MUPs) (10). As mentioned elsewhere, MUP evaluation is not recommended in the paraspinal muscles. In addition, routine use of thinner, monopolar needles (typically 0.33 to 0.40 mm) is suggested as less painful and less likely to cause hemorrhage.

EMG equipment should be inspected regularly for leakage current and ground electrodes (third lead) should be used consistently. Stimulation near pacemakers and catheters leading to major vessels is avoided, or supervised by an appropriate specialist when necessary. In general, the risk of electrical injury is greatest in the presence of a wire or fluid-filled catheter that penetrates the skin (creating a current path), in contrast to the lower risk of stimulation near a fully implanted pump or pacemaker (9). The electrodiagnostic consultant should practice within his or her training or experience when examining around the torso so as to avoid an unnecessary risk of pneumothorax or peritonitis.

Satisfaction: Patients and Referral Sources

First impressions are important, and patients’ confidence in the provider and trust in the advice received will be improved if they see a friendly and efficient office staff when they enter the facility. Smiles and respectful attitudes make the relative drudgery of registration and billing paperwork a bit easier and encourage patients to relax in an unfamiliar environment. Addressing patients by their surname or full name is recommended rather than using the first name, especially on their first visit to the office. Staff should not shout names or use over-friendly terms such as “Baby” or “Sweetie.”

Referring physicians and their key staff members are valuable partners for the electrodiagnostic medicine consultant because they can select the appropriate patients who can be helped through testing and can influence these patients’ perceptions as they prepare for the visit. Continued communication with them, in the form of reports that clearly explain the findings as well as verbal communication in unusual cases, is important to these relationships. Electromyographers can also provide formal or informal education about the medical management of neuromuscular problems, as well as patient education materials describing how to prepare for an EMG test. The knowledge of the referral source and his or her ability to transmit it and properly prepare the patient for the procedure greatly improves the patient’s perceptions and response to the unusual situation of the EMG laboratory.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree