Abstract

Psychotherapy for affective/behaviour disorders after traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains complex and controversial. The neuro-systemic approach aims at broadening the scope in order to look at behaviour impairments in context of both patient’s cognitive impairments and family dysfunctioning.

Objective

To report a preliminary report of a neuro-systemic psychotherapy for patients with TBI.

Patients and methods

All patients with affective/behaviour disorders referred to the same physician experienced in the neuro-systemic approach were consecutively included from 2003 to 2007. We performed a retrospective analysis of an at least 1-year psychotherapy regarding the evolution of the following symptoms: depressive mood, anxiety, bipolar impairment, psychosis, hostility, apathy, loss of control, and addictive behaviours as defined by the DSM IV. Results were considered very good when all impairments resolved, good when at least one symptom resolved, medium when at least one symptom improved, and bad when no improvement occurred, or the patient stopped the therapy by himself.

Results

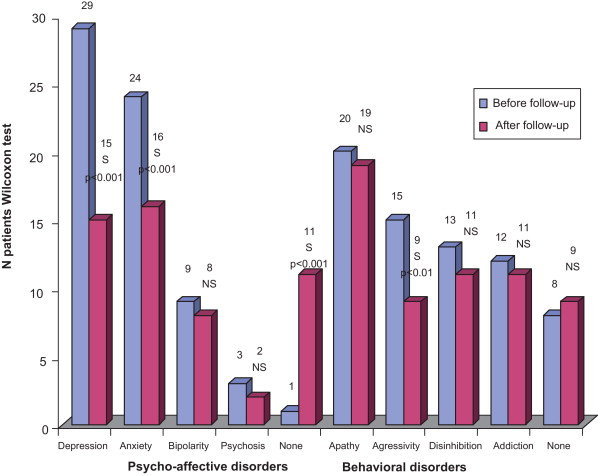

Forty-seven patients, 35 men and 12 women, with a mean age of 33.4 years, were included. Most suffered a severe TBI (mean Glasgow coma score: 6.4) 11 years on average before the inclusion. At the date of the study, 11 patients (23%) had a poor outcome, 23 (48%) suffered Moderate disability and 13 (27%) had a Good recovery on the GOS scale. All therapy sessions were performed by the same physician, with 10 sessions on average during 13.5 months. Results were classified very good in six cases (13%), good in 18 others (38%), medium in 10 patients (21%) and bad in 13 cases (27%). We observed a significant improvement of affective disorders, namely anxiety ( P < 0.001) depressive mood ( P < 0.001) and hostility ( P < 0.01). However, bipolar symptomatology, apathy, loss of control and addictive disorders did not improve.

Discussion/conclusion

From our best knowledge, this is the first clinical report of neuro-systemic psychotherapy for affective/behaviour disturbances in TBI patients. This kind of therapy was shown to be feasible, with a high rate of compliance (72%). Psycho-affective disorders and hostility were shown to be more sensitive to therapy than other behaviour impairments. These preliminary findings have to be confirmed by prospective trials on broader samples of patients.

Résumé

Le suivi psychothérapique ambulatoire des traumatisés crâniens est un sujet complexe et encore très mal connu. L’approche neurosystémique propose d’élargir le regard et le champ psychothérapique en incluant les troubles cognitifs, ainsi que les dysfonctionnements relationnels entre patient et famille, et parfois institution soignante, considérant les troubles du comportement comme un symptôme de cette crise.

Objectif

Présenter une expérience de suivi psychothérapique systémique individuelle en secteur ambulatoire, en collaboration avec un service d’accompagnement pour traumatisés crâniens.

Patients et méthodes

Tous les patients traumatisés crâniens adressés de 2004 à 2008 par un réseau médico-social pour un suivi psychothérapique à un médecin libéral spécialiste de médecine physique et réadaptation formé à l’approche neurosystémique ont été inclus. L’analyse a porté sur la présence un an au minimum après le début de la prise en charge de troubles affectifs : dépression, anxiété, bipolarité, psychose ou de troubles comportementaux : agressivité, apathie, désinhibition, addiction, selon les critères du DSM4. Les résultats ont été classés en quatre groupes : groupe 1 : disparition des troubles ; groupe 2 : disparition d’au moins un trouble ; groupe 3 : amélioration d’au moins un trouble ; groupe 4 : pas d’amélioration ou perdu de vue. L’analyse statistique des résultats a été effectuée en mode univarié par tests non paramétriques.

Résultats

On note que 47 patients ont été inclus : 35 hommes et 12 femmes, âgés de 33,4 ans en moyenne. Le traumatisme datait de 11 ans en moyenne. Il s’agissait pour la plupart de traumatismes crâniens graves, avec un score de Glasgow initial moyen de 6,5. Au moment de l’étude, 11 patients (23 %) présentaient un handicap sévère (GOS 3), 23 (48 %) un handicap modéré (GOS 2) et 13 (27 %) avaient une bonne récupération (GOS 1). Les entretiens neurosystémiques ont tous été effectués par le même praticien. La durée de suivi a été de 13,5 mois, avec dix entretiens un recul moyen de 26,4 mois.

Résultats quantitatifs

On relevait en fin d’étude six patients dans le groupe 1 (13 %), 18 dans le groupe 2 (38 %), dix dans le groupe 3 (21 %) et 13 dans le groupe 4 (27 %).

Résultats qualitatifs

Il existait une amélioration significative globale des troubles affectifs ( p < 0,001), en particulier, de l’anxiété ( p < 0,001) de la dépression ( p < 0,001) et de l’agressivité ( p < 0,01), mais pas d’amélioration significative des troubles du comportement, de la bipolarité, de la psychose, de l’apathie, de la désinhibition ou de l’addiction.

Discussion/conclusion

Il s’agit de la première étude consacrée à la prise en charge psychothérapique systémique individuelle des traumatisés crâniens en secteur de ville. La faisabilité est satisfaisante, 72 % des patients ayant acceptés le suivi. Les résultats semblent meilleurs sur les troubles affectifs que sur les troubles comportementaux en dehors de l’agressivité. Ces données préliminaires restent à confirmer par un travail prospectif sur une plus grande échelle.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The psychological or neuropsychiatric disorders, both emotional and behavioral, of traumatic brain injury patients represent one of the major problems in the repercussions phase, effecting 50% to 70% of these patients with serious consequences for their personal, family and the socioprofessional lives . One year after the accident, 40% present more than two psychiatric symptoms . Most of the authors recommend psychotherapy — whether it be individual psychodynamic therapy , individual or group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) , or holistic therapy — with the caveat of adapting the technique to the specific disorders of traumatic brain injury patients .

Recently, the authors were also interested in caring for the families and caregivers, who are now included in the information and support programs . These programs can sometimes underestimate the complexity of the individual and family situations. The family neuro-systemic approach, developed by Destaillats et al. and used by other authors , proposes a complex approach to these difficulties, according to three points of view: individual, institutional and family. It calls on semi-direct interviews based on systemic hypotheses, which seems to us particularly appropriate to the situation of these patients and their circles of friends and family.

After several years of training and working in the Handicap and Family service of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (MPR) department of the University Hospital Center of Bordeaux, we tried to widen this approach to include the individual support of ambulatory traumatic brain injury patients. We present, here, the results of a preliminary evaluation for the first 5 years.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Population

Our study’s population is all of the traumatic brain injury patients sent to our office between 2004 and 2008 for a psychological monitoring by the Mobile Support Service for Traumatic Brain Injury Patients ( Service mobile d’accompagnement de traumatisés crânien : SMATC) in the ADAPT of Bordeaux.

1.2.2

Therapy description

The individual neuro-systemic approach has the goal of reducing the emotional and behavioral disorders of the traumatic brain injury patients by improving the relational dysfunctions within the various systems including the patient (e.g., family, conjugal, social, institutional, professional), while taking into account the patient’s specific cognitive disorders. The therapy begins with three interviews: a precise evaluation of the situation, patient history, and cognitive and psychological disorders. The first interview is carried out in the presence of a case manager or a close relative.

The following things are completed:

- •

the most detailed patient history possible of the traumatic brain injury (TBI), including accident circumstances, the initial Glasgow score, brain damage CAT scan, coma length, and post-traumatic amnesia, evolution, the last neuropsychological assessment, and current treatments, for example;

- •

the family and psychiatric history;

- •

the current socioprofessional situation, completed with information supplied by the support team or the spouse;

- •

the patient conditions (i.e., the patient’s emotional problems and the behavioral problems observed by their family and friends in daily life and in the sessions by the examiner) (This distinction seemed to be fundamental to meet the expectations of the patient and the support team. In fact, there are frequently conflicts between an anosognosic patient that supposedly has no emotional problems but has significant behavioral problems. On the contrary, a depressed patient does not have annoying behavioral problems but feels an intense psychological suffering, which requires psychotherapy);

- •

the complaints or the questions of the support team, the spouse and/or the family.

Psychological support is proposed. The psychotherapy’s operating procedure and the link between the therapist and the service is explained. If needed, medicine is prescribed. Taking place one to two times a month, the semi-direct interviews are face-to-face, include active listening, and last from 45 minutes to 1 hour. The patient has time to express him/herself, taking into account the difficulties linked to neurological disorders (e.g., slowness, fatigability, dysarthria).

In addition to soothing the distress by listening and psychological support, the therapeutic objectives are:

- •

to give some answers and meaning for the distress and the relational, psychological or behavioral difficulties, by using an approach based on development and verifications of systemic hypotheses;

- •

to help to elaborate new and more correct representations for the emotional, family and social relationships, based on the study of the family and the genogram, among others; this objective is particularly important for the patients who are victims of emotional deprivations, humiliations, ill-treatment or childhood sexual abuse;

- •

to offer a reference location for the psychological support of the patient, his/her family and support team.

Working in networks, there is a meeting to exchange information with the SMATC team once a month. The end of the therapy is decided with the patient and the support team at the request of one or the other, when the symptoms have improved or when the patient questions have been answered. Mainly, the therapy is ended progressively, by spacing out the sessions from 2 to 3 months every 6 months approximately.

1.2.3

Evaluation criteria and data processing

During October 2009, the cases were analyzed by evaluating the psychiatric symptoms in the beginning of the psychotherapy compared with at least 1 year of the treatment. The main evaluation criteria were the results of the therapy for the evolution of the symptoms. These symptoms were classified according to the DSM IV criteria in two categories: psycho-emotional disorders (anxiety, depression, bipolarity, psychosis) and behavioral disorders (aggressivity, disinhibition, apathy, addiction).

The follow-up results for every case were classified in four categories, according to the evolution of the initial symptoms: poor results means no improvement of the symptoms or the patient dropped out of sight; average results means an improvement of at least one symptom; good results means the disappearance of at least one symptom; and very good results means the disappearance of all of the symptoms.

The Pearson Chi 2 test, Kruskal-Wallis test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to conduct a univaried analysis and a correlation search. For every failure, a detailed qualitative analysis was made to search for a causality factor.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Patient description

Forty-seven patients were monitored from 2004 to 2008: 35 men (74%) and 12 women (26%), with an average age of 33.4 years. Every patient suffered a traumatic brain injury, dating 11 years on average, with an average Initial Glasgow Score of 6.5 ( Table 1 ). This study results show the handicap was classified severe (Glasgow Outcome Scale [GOS] 3) in 23% of the cases and light to moderate (GOS 1 and 2) in 77% of the cases.

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (74%) |

| Female | 12 (26%) |

| Average age | 33.4 ± 9.1 years |

| Average Initial Glasgow Score | 6.5 ± 0.7 |

| Average post-TBI delay | 11.1 ± 7.5 years |

| History of childhood ill-treatment (humiliations, violence, sexual abuse) | 27 (57%) |

| Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) | |

| GOS 1 | 13 (27.7%) |

| GOS 2 | 23 (48.9%) |

| GOS 3 | 11 (23.4%) |

| Environment | |

| Individual | 21 (44.7%) |

| Collective | 21 (44.7%) |

| Living with family | 5 (10.6%) |

| Marital situation | |

| Single | 39 (83%) |

| Couple | 17 (17%) |

| Professional situation | |

| Unemployed | 29 (61.7%) |

| Adapted job | 13 (27.7%) |

| School/University | 3 (6.4%) |

| Ordinary job | 2 (4.3%) |

| Initial psychotropic treatments | 28 (59.6%) |

| Distribution of psychotropic treatments | |

| Antidepressant | 42% |

| Anxiolytics | 15% |

| Thymo-regulators | 15% |

| Antipsychotics | 8% |

Housing is an individual house in 44% of the cases, collective housing in 44% of the cases, and a family home in 12% of the cases. The patients are single in 83% of the cases, and married or living together in 17% of the cases. They are unemployed in 61% of the cases, have adapted job in 21% of the cases, are in school or university in 6% of the cases and have an ordinary job in 4% of the cases.

Sixty percent of the patients take psychotropic treatments: in 42% of the cases, they take antidepressants; in 15% of the cases, they take anxiolytics; in 15% of the cases, they take thymo-regulators; and in 8% of the cases, they take antipsychotics. In 63% of the cases, the patients had serious traumas when children: educational deficiencies, emotional deprivations, humiliations, ill-treatment or sexual abuse.

1.3.2

Follow-up time and number of interviews

The average time of psychotherapeutic follow-up ( Table 2 ) was 1.1 years, with an average of 2.2 years before they started getting treatment. During the follow-up period, the patients benefited from one family consultation and an average of 9.8 individual consultations.

| Average length of the follow-up | 13.5 months | SD: 10.2 |

| Average drop after the end of the follow-up | 2.2 years | |

| Average number of individual interviews | 9.8 | SD: 7.8 |

| Average number of family interviews | 1 | SD: 1.4 |

1.3.3

Results of the neuro-systemic approach

Table 3 shows the global results. The results are seen as good or very good in 50% of the cases, average in 21% of the cases, and the poor in 27% of the cases. They are statistically correlated for the follow-up time ( P < 0.05) and for individual interviews ( P < 0.01), as well as in the severity of the disability (GOS 3; P < 0.05) ( Table 4 ). In case of failure, the average follow-up time and the number of consultations is half as many as the average for the population, or respectively 6.7 months for the failed cases vs. 13.5 months of follow-up time for the improved group, and five consultations for the failed cases vs. 9.8 consultations for the improved group.

| Group 1: very good (disappearance of the symptoms) | 6 | 12.8% |

| Group 2: good (disappearance of at least one symptom) | 18 | 38.3% |

| Group 3: average (improvement of at least one symptom) | 10 | 21.3% |

| Group 4: poor (no improvement or patient dropped out of sight) | 13 | 27.7% |

| Test used | Parameter value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Pe | 7.7 | 0.06 ns |

| Average age | KW | 4.3 | 0.2 ns |

| Initial Glasgow Score | KW | 4.5 | 0.2 ns |

| Post-TBI delay | KW | 0.4 | 0.9 ns |

| History of ill-treatment | Pe | 5.5 | 0.1 ns |

| Glasgow Outcome Scale a | Pe | 13.4 | 0.04 s |

| Environment | Pe | 5.7 | 0.5 ns |

| Marital situation | Pe | 0.1 | 0.9 ns |

| Professional situation | Pe | 5.2 | 0.8 ns |

| Follow-up time | KW | 10.3 | 0.02 s |

| Treatments | Pe | 2.9 | 0.4 ns |

| Number of individual interviews | KW | 13.3 | 0.004 s |

| Number of family interviews | KW | 0.5 | 0.9 ns |

The main causes of failure are anosognosia in 38% of the cases, and the lack of patient motivation in 30% of the cases ( Table 5 ). Most of the time, the failures arose very early, sometimes at the first therapy session. The patient became conscious of the work to be done and refused to do it due to anosognosia, distrust, or lack of desire to change. Two other causes of failure are the family reluctance to follow-up in two cases, and the intensity of the addiction with a categoric refusal to stop drinking alcohol in two cases.

| Anosognosia | 5 | 38% |

| Lack of patient motivation | 4 | 30% |

| Family reluctance to follow-up | 2 | 16% |

| Refusal to give up drinking alcohol | 2 | 16% |

| Total | 13 |

1.3.4

Qualitative results

As shown in Fig. 1 , the qualitative analysis highlights a high frequency of psychological disorders before the beginning of the therapy: 46 patients (98%) had at least one psychological disorder and 37 patients (79%) had a behavioral disorder; both types of disorders were associated in 38 cases (81%). Depression (29 cases; 61%) and anxiety (24 cases; 51%) were the most frequent, while bipolarity (9 cases; 19%) and psychosis (3 cases; 6%) were less frequent. The behavioral disorders were distributed in fairly homogeneously: apathy (20 cases; 42%), aggressivity (15 cases; 32%), disinhibition (13 cases; 27%), and addiction (12 cases; 25%).

After the therapy, a significant improvement was noted in the psycho-emotional disorders, which disappeared completely for 10 patients ( P < 0.01), while the behavioral disorders disappeared completely only in one case. Among the psycho-emotional disorders, especially depression and anxiety were improved significantly ( P < 0.001), respectively disappearing in 14 patients (48%) and eight patients (33%). Bipolarity and psychosis were not improved significantly. Among the behavioral disorders, only the aggressivity was significantly improved ( P < 0.01) in six patients (40%); apathy, disinhibition and addiction remained unchanged.

1.4

Discussion

For a long time, the psychotherapy for traumatic brain injuries has been dominated by the psychoanalytical approach in France and the cognitive behavioral approach in the Anglo-Saxon countries for cultural reasons. Both approaches are efficient and have demonstrated advantages in clinical studies or case analyses for the institutional sector. Recently, family therapy , especially systemic family psychotherapy , has been recommended in addition to individual psychotherapy. Although implemented for more than 15 years by the Bordeaux team , the family neuro-systemic approach has not been the subject of a published clinical study until now. In addition, while a majority of patients are monitored after they released from the institutions by psychiatrists or psychologists, we found no data in the literature on their results. To the best of our knowledge, this first published study on the psychological follow-up using the neuro-systemic approach with a cohort of ambulatory traumatic brain injury patients.

This study is an exploratory study in which the results must be considered with prudence. First of all, it is a retrospective open study without control group. Even though we tried hard to standardize the semiology with reference to DSM IV, the evolution under treatment remains difficult to evaluate exactly, especially as the psychotherapy context does not permit separating the evaluator from the therapist. There was also probably an interaction between medicine and systemic psychotherapy. There is probably a synergic effect of these parallel therapies, as Soo et al. found in his review of the literature about CBT. Finally, we systematically classified the patients who dropped out of sight and stopping the therapy sessions with the poor results, when the other factors could have intervened with some of the patients. By keeping these limits in mind, the study nevertheless highlights interesting data.

First of all, the good feasibility of this therapy must be underlined, as demonstrated by the relative low rate of patients who dropped out of sight. Considering the cognitive disorders of the patients and the non-institutional character of the psychotherapy, we would have expected a higher rate of abandonment or memory lapses. Another element of satisfaction is the large number of interviews performed per patient: an average of 11 (among which at least one family interview) over a period of 13.5 months. We were afraid a mediocre compliance with this population, considering the cognitive and behavioral disorders.

These results can be explained by a good collaboration with the team of Medical-Social Support Service for Handicapped Adults ( Service d’accompagnement médico-social pour adultes handicapés : SAMSAH), which performs a stellar job for support and assistance, and a good adaptation of the neuro-systemic interview technique for this type of patients. In fact, the semi-direct interviews and their length (45–60 mn), the issues tackled (e.g., disability, emotions, traumatic history, family, sexuality), and the therapist taking cognitive disorders into account were very appreciated, according to numerous spontaneous statements. The cognitive disorders were not a major obstacle to therapy, with the caveat of having identified them correctly and taking them into account in the interviews.

The study’s good global results must be noted, with an improvement of the disorders in 73% of the cases, correlated to number of interviews. This pleads in favor of the therapy’s efficiency, even though it must be taken into account the beneficial effect of the patient’s social focus and the medicine taken during the follow-up period. The best results are obtained for the most handicapped patients. GOS 3 patients (severe handicap) vs. GOS 2 patients (moderate handicap), the most handicapped patients often had a lower level of awareness of the disability and thus lower expectations.

On the qualitative plan, the improvement concerns especially the patients with depression, anxiety and aggressivity. These observations have been already reported by the other authors in a CBT context or, more recently, following music therapy sessions . This sensory approach seems to be interesting and evokes the other techniques with physical mediation, such as the hypnosis or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). We use regularly EMDR but have not explored this subject with specific studies for the traumatic brain injury patients yet. It is certainly a vast field for exploration in the future.

Despite the lack of statistically significant differences, the role of medicinal treatment has to be taken into account. At the beginning of the therapy, two thirds of the patients had begun, or modified, a treatment of antidepressants or thymo-regulators. Most of the studies summarized in Richard and Ferrapie’s literature review found efficient the medicinal treatment offered for depression, anxiety and aggressivity. However, certain authors found a minimal benefit of medicinal treatments with respect to non-medicinal approaches. Certain behavioral disorders, such as apathy and disinhibition, are not improved by the therapy, probably due to their organic etiology. Similarly, addiction is not very sensitive to the individual therapy, requiring recourse to specialized structures.

The case-by-case analysis of the failures and the patients who dropped out of sight allowed us to identify several causes. The first cause is unmistakably anosognosia, which entails incomprehension of the interest of the psychotherapy, and sometimes blocking the therapist in a context of rationalizing the disorders. In three cases, the patients completely refused to think about their cognitive disorders, generally projecting their difficulties on their family/friends or on the nursing staff. The second cause is the lack of patient motivation; in these cases, the psychotherapy responded to more the demands of the support team, the family circle, or the spouses, than a real demand of the patient. These patients were not anosognosic, but they did not want a psychotherapist to solve their problems. In two cases, the refusal to stop drinking alcohol encountered the same process.

1.5

Conclusion

The results of our study, to be interpreted with the customary methodological precautions, are unmistakably positive, finding a good patient participation and an improvement of the psychological state in two thirds of the cases, correlated to the follow-up time and the number of therapy sessions. Anxiety, depression and aggressivity were improved; apathy, disinhibition and addiction were not improved. Even though there are still points to be improved, such as the failure rates and the patients who dropped out of sight, in our opinion, the individual neuro-systemic approach seems to be appropriate for the psychological support of ambulatory traumatic brain injury patients. Additional research with a control group and a subjective analysis of the quality of life will be studied to better validate this hypothesis.

This study was the subject of a paper in 24th SOFMER Congress in Lyon on 23 October 2009 and obtained the Allergan Sofmer Cofemer prize for “improvement of the quality of life 2009”.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like thank Jean-Paul Mugnier, Director of the Institute of Systematic Studies, for the quality of his classes and his supervision, and Professor Michel Barat who gave me the taste of the scientific rigor and the meaning of being human.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree