Abstract

Buruli ulcer (BU), an emerging disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans , causes severe impairments. In literature, no survey has been devoted to the cured patients returned back home.

Objective

To analyze the long-term psychosocial, professional and family repercussions of BU on former patients.

Method

Cross-sectional descriptive and analytic study on 244 formers patients seen at the Screening and Treatment BU Center of Allada from 2005 to 2009 and followed at home from January to July 2010.

Results

On the psychosocial level, 50.8% cured patients attributed the disease to witchcraft (mostly adults and teenagers); 90. 2% did not feel guilty (mostly children), 48.9% of the adults felt diminished, 31.7% are depressed and 19.5% anxious. On professional level, 81.0% of workers had gotten back to work, in the same job for 75.0% of them while 25.0% had changed jobs; 90.1% of children went back school, 29.4% followed a normal schooling but 70% did experience academic delay. On family level, 2.5% of patients were rejected by their families.

Conclusion

After returning home, former UB patients suffered of severe psychosocioprofessional and familial repercussions that suggested an organization of their home monitoring.

Résumé

L’ulcère de Buruli (UB), maladie émergente due au Mycobacterium ulcerans , est génératrice de séquelles lourdement invalidantes. Dans la littérature, aucune étude ne s’est intéressée aux patients guéris retournés à leur domicile.

Objectif

Analyser le devenir psychosocioprofessionnel et familial des anciens patients guéris d’UB.

Méthode

Étude transversale descriptive et analytique portant sur 244 anciens patients, suivis au centre de dépistage et de traitement de l’UB d’Allada de 2005 à 2009 et revus à leur domicile de janvier à juillet 2010.

Résultats

Sur le plan psychosocial, 50,8 % ont attribué la maladie à la sorcellerie (adultes et adolescents surtout) ; 90,2 % ne se sont pas culpabilisés (enfants surtout), 48,9 % des adultes se sont sentis diminués, 31,7 % déprimés et 19,5 % anxieux. Au plan professionnel, 81,0 % des travailleurs ont repris leurs activités dont 75,0 % les mêmes, alors que 25,0 % ont changé de profession ; 90,1 % des enfants ont repris les cours, 29,4 % ont évolué normalement mais 70 % ont perdu d’années scolaires. Au plan familial, 2,5 % des patients sont rejetés par leurs familles.

Conclusion

Après leur retour à domicile, les patients guéris d’UB subissent des conséquences psychosocioprofessionnelles et familiales lourdes imposant l’organisation de leur suivi dans leur milieu d’origine.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Buruli ulcer (BU) is an emerging disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium ulcerans (Mu). It occurs in endemic areas in countries with tropical and subtropical climates (Africa, Southern America, Asia and the South Pacific ). Even though the mortality rate for BU is very low, the real issue lies in delayed treatment which may cause long-term functional disabilities and impairments as well as restricted participation in 25% of cases according to the WHO . These impairments and disabilities, in various degrees of severity, linger in patients cured of BU even when physical rehabilitation was part of the therapeutic array . Managing their impairment and disability within their living environment has become a real issue for former patients. Furthermore, even though physical rehabilitation was recognized as an essential part of BU treatment, no study has ever focused on this issue. This study explores the psychosocioprofessional and family repercussions of BU in former patients within their home environments.

1.2

Patients and study methods

1.2.1

Patients

The study population included patients treated and monitored for BU and declared cured at the Allada Center for Screening and Treatment of Buruli Ulcer (CDTUB) from 2005 to 2009. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria described below were enrolled in the study.

1.2.1.1

Inclusion criteria

Patients who were screened, treated and declared cured at the Allada CDTUB from January 2005 to December 2009.

Patients had to be in the CDTUB database with information on their home address or they had to be identified by the community networks – Former BU patients who lived in Benin within a 100 km radius from the Allada CDTUB (Allada CDTUB geographical area) during the study.

1.2.1.2

Exclusion criteria

BU relapse.

All patients with a history of disorders that could have an influence on their psychosocioprofessional and family lives (high blood pressure, diabetes, psychiatric disease and bone fracture in the affected limb).

1.2.2

Study method

1.2.2.1

Type of study

This cross-sectional, descriptive and analytic study was conducted from January to July 2010 in the Allada CDTUB geographical area, in the Atlantic Department of Benin. By geographical area we mean the area within a 100 km radius of the Allada center where the patients were screened and treated.

1.2.2.2

Description

In the Allada CDTUB database, we found 347 patients treated and declared cured during the study period, i.e. January 2005 to December 2009. With the help of the BU community networks that kept in touch with these former patients over the years and promoted the trust and acceptation of patients to participate in the study, we made appointments with patients meeting the inclusion criteria described above and met with them in their home environments. In all, 244 patients were included in the study and seen at home. For the 103 remaining patients, 20 were lost to the touch by the community networks, 22 went to Nigeria to find work, 30 were preschool children who could not answer our questions, 18 were always no-shows despite having made appointments with them, which we considered a refusal to participate in the study, finally 13 had died of various causes.

During the home visit, the patients answered a questionnaire and had a full physical check-up. The questionnaire explored their psychosocioprofessional and family experience with closed or open answers to the various questions asked.

Concerning their specific psychological experience, we used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) developed by Sigmond Snaith. When the total points for anxiety and/or depression was less than 10, we came to the conclusion that the patient was not depressed or anxious; but when the sum was greater than 10, the patient was either anxious or depressed depending on the case. This allowed the differentiation between anxious and depressed patients. Finally in the questionnaire we asked adolescent, adult and elderly patients if they felt diminished compared to their peers.

1.2.2.3

Study variables

The study variables are:

- •

patient’s psychological experience of the disease;

- •

hospital stay experience;

- •

family acceptance;

- •

impact of the disease on professional activities;

- •

impact of the disease on children’s schooling;

- •

schoolmates’ behavior after children went back to school;

- •

children rejected by schoolmates, excluded during recess, being taunted, insulted;

- •

impact of the disease on academic learning;

- •

impact of the disease on family life.

1.2.2.4

Data analysis

After the study data were entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft office Excel 2007), statistical analyses were conducted with the EPI software version 3.4.3. Graphs were elaborated with Microsoft office Excel 2007. We used the Chi 2 test and Fischer statistic test: the significant difference was set at P < 0.05.

1.2.2.5

Ethics

This study was approved by the National Program for Fighting Leprosy and Buruli Ulcer (Programme national de lutte contre la lèpre et l’ulcère de Buruli). This approval was the best ethic caution we could have obtained for this type of study. Data were collected after having obtained the oral informed consent of patients and/or their parents. During the entire study, we strictly respected the patient anonymity and confidentiality and abided by the oath of medical secrecy.

1.2.2.6

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Demographics

1.3.1.1

Age

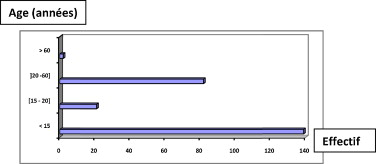

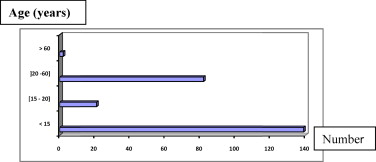

The mean age of patients in our study was 8 years (range: 6–89 years), 57% ( n = 139) of patients were children under the age of 15; there were very few elderly patients with 0.81% ( n = 2). Fig. 1 shows the repartition of patients according to age ranges.

1.3.1.2

Gender

Among the patients, 50.4% were men and 49.6% were women. The sex-ratio was 1.01. In children, boys were predominant with 65.5% ( n = 91).

1.3.2

Psychosocioprofessional and family repercussions of BU on former patients

1.3.2.1

Psychological impact of the disease, guilt and conception of the disease, family acceptance and hospital stay experience

Table 1 lists the psychological impact of the disease, guilt, conception of the disease, family acceptance and hospital stay experience. The two patients over the age of 60 were not represented. None of them felt any guilt; they were both well accepted within their family. One was anxious, the other felt diminished. Children believing that BU was a natural disease (604%) were predominant than those who attributed BU to witchcraft. Adolescents and adults most often believed in witchcraft, i.e. respectively 52.4% and 69%. Overall, few patients felt guilty. Hospitalization was reported as a negative experience by most patients, regardless of age. Furthermore, family acceptance was very important in these four categories of patients. Regarding their psychological experience, more adolescents and adults reported feeling diminished (respectively 52.4% and 48.9%) than anxious (23%) and depressed (31%).

| Modality | > 15 years | [15 20[ | [20 60[ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Conception of the disease | Witchcraft | 55 | 39.6 | 11 | 52.4 | 57 | 69.5 |

| Natural disease | 84 | 60.4 | 10 | 47.6 | 25 | 30.5 | |

| Guilt | Yes | 19 | 13.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 4 | 4.9 |

| No | 120 | 86.3 | 20 | 95.2 | 78 | 95.1 | |

| Hospital stay experience | Difficult | 95 | 68.3 | 12 | 57.1 | 64 | 78.1 |

| Bearable | 43 | 30.9 | 9 | 42.9 | 18 | 21.9 | |

| Enjoyable | 1 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Family acceptance | Yes | 136 | 97.8 | 21 | 100.0 | 79 | 96.3 |

| No | 3 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.7 | |

| Psychological experience | Diminished | 11 | 52.4 | 40 | 48.9 | ||

| Anxious | 5 | 23.8 | 16 | 19.5 | |||

| Depressed | 5 | 23.8 | 26 | 31.7 | |||

1.3.2.2

Impact on professional activities

It was found out that 81.0% of workers ( n = 68) went back to their job, 75% ( n = 51) of them resumed their former professional activity whereas 25% ( n = 17) changed jobs.

Out of the 19% of patients who did not get back to work, 13.1% ( n = 11) were not able to get back to work because of impairments and 5.9% ( n = 5) because of pain or lack of support.

1.3.2.3

Impact on schooling

1.3.2.3.1

Getting back to school

While 90.1% of primary school, middle school, high school and college students ( n = 136) went back to school, only 9.9% of patients ( n = 15) did not go back. Among these 9.9%, 4% ( n = 6) reported a limitation of their functional abilities and 5.9% did not have any support or feared a recurrence of the disease upon getting back to school.

1.3.2.3.2

School evolution

It is noted that 29.4% ( n = 40) had a normal evolution without academic delay, 45.6% ( n = 62) lost one school year, 17.6% ( n = 24) lost two school years and 7.4% ( n = 10) lost three school years and more.

1.3.2.3.3

Acceptance by schoolmates

Upon getting back to school, 63.2% of patients were well accepted by their schoolmates and 36.8% experienced rejection.

1.3.2.4

Impact of the disease on professional training

All professionals in training went back to their program.

1.3.2.5

Impact of the disease on family life

Among the patients, 3.3% ( n = 8) got married after their disease and 0.4% ( n = 1) of them got a divorce because of the disease; 68.4% of patients assumed fully their responsibilities as spouse, parent or child whereas 31.6% did not manage to do so.

1.3.3

Factors influencing the psychosocioprofessional and family experience of former patients

1.3.3.1

Impact of the psychological experience of the disease

Table 2 lists all factors having an impact on the patients’ psychological experience of their disease. This psychological experience is influenced by professional life and family responsibilities.

| Diminished | Anxious | Depressed | Statistic tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional activity | ||||

| Same job | 17 | 12 | 22 | Chi 2 = 15.33 |

| New job | 11 | 05 | 01 | ddl = 4 |

| Unemployed | 12 | 01 | 03 | P = 0.004 |

| Responsibilities | ||||

| Assumed | 65 | 25 | 77 | Chi 2 = 14.3 |

| Not assumed | 44 | 17 | 16 | ddl = 8; P = 0.008 |

1.3.3.2

Impact of the conception of the disease

Table 3 highlights factors having an impact on the patients’ conception of the disease. Neither their professional activities, nor their family life had an impact on their conception of the disease.

| Natural disease | Witchcraft | Statistic tests | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional life | |||

| Same job | 17 | 34 | Chi 2 = 1.34; ddl = 2; P = 0.51 |

| Different job | 06 | 11 | |

| Unemployed | 03 | 13 | |

| Family life | |||

| Assuming responsibilities | 89 | 78 | Chi 2 = 3.59; ddl = 1; P = 0.058 |

| Not assuming responsibilities | 31 | 46 | |

1.3.3.3

Impact of schoolmates’ acceptance on academic evolution

Table 4 unveils the influence of schoolmates’ acceptance on the number of school years lost by former BU patients.

| Acceptance | Rejection | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 33 | 07 |

| 1 year | 35 | 27 |

| 2 years | 16 | 08 |

| 3 years and more | 02 | 08 |

1.4

Discussion

Patient repartition according to age shows that BU affects all ages (6 to 89). The mean age of patients in our series was 8 years and the great majority, i.e. 57% of them, was younger than 15 years old. Children seems the most exposed to BU. This could be explained by the fact that they play and swim frequently in rivers and water holes. Furthermore, the frequent wounds incurred by children when playing are an entryway for M. ulcerans . Most authors who worked on BU came up with similar results and explanations . Some authors put forward the weak immune system of these children , while partly true, this explanation is up for discussion since the elderly, who also have a weaker immune system are scarcely affected by the disease 0.8% ( n = 2).

In our study, the population included 50.4% of men and 59.6% of women with a sex-ratio at 1.01. Our results did not highlight any gender predominance. The exposure to the disease, climate and environmental factors are the same for both genders. In spite of these elements, these results remain intriguing as we were expecting a predominance of male patients. In fact, boys are rowdier, more curious and tend to play more in the water and thus end up being more affected (65%) in the below 15 years age range, whereas in that age range girls (35%) are more protected by their parents and do not play rough games. Our results are similar to those reported by Sopoh et al. , Josse et al. and Asiedu et al. . Barker and Kadio brought up higher rates in girls than boys in Ivory Coast. Conversely, Van der Werf reported higher rates in men than women in Ghana.

Results analysis from Table 1 showed that more children (60.4%) believed BU to be a natural disease versus those who attributed it to witchcraft. In the group of adolescents and adults, more patients believed BU was due to witchcraft with 52.4% of adolescents and 69% of adults. Overall, for all patients attributing the disease to witchcraft (50.8%), more than 55% of them were adolescents or adults. This tends to show that as they get older, patients are more influenced by the dominant African conception of the disease. In fact, childhood is the age of innocence and believing in natural phenomena. Furthermore, we believe that the therapeutic education given to children regarding BU transmission, physiopathology and clinical symptoms as part of Communications for Behavioral Changes (CBC) during their hospital had an impact on their conception of the disease. School also contributed to their natural conception of the disease. However, with age, life experience, elements of information received from all sources and the increasing influence from environmental factors, patients become more sensitive to society’s interpretation of phenomena. In sub-Saharan Africa, the onset of disease or death is often attributed to supernatural causes. In fact, at first patients believe that the disease originates from an anthropomorphic power: sorcerer, genie, ancestor or God himself then secondarily they recognize that the disease stems from a noxious agent perceived as natural: environment (influence of the climate, ecological conditions and social environment) . These considerations often delay the moment when patients finally decide to see a doctor. Fortunately, this African conception of the disease did not have an impact on the psychosocioprofessional and family life experience of these former patients. Overall, very few patients felt guilty, regardless of age. In fact, more than 90% of patients ( n = 220) did not feel any guilt (86.3% of patients). Should this result be linked to the African conception of the disease? It is true that if the onset of the disease is due to an invisible ominous force, as underlined by the African beliefs, there can be no guilt.

Being hospitalized was reported as a poor experience by most patients (more than 70%) regardless of age. This result is not surprising when we understand the poor hospitalization conditions in Benin where numerous patients have to share a very small room. Regardless of the habitat, people in Benin prefer to live at home. A hospital stay means that patients and family members supporting them have to stop working. Thus difficulties arise and linger on for fulfilling basic needs such as eating, housing, etc. Direct and indirect costs of BU treatment in the hospital are hard to manage, even impossible sometimes, in spite of the various subventions from welfare organizations. These results are similar to those reported by Johnson et al. and Stienstra et al. .

Family acceptance was high in the four different age ranges. This can probably be explained by the legendary African solidarity, which, in spite of its weakening in large cities, is a true reality in the countryside where BU is predominant.

Finally, regarding the psychological experience, more adolescent patients reported being diminished (52.4%) than anxious or depressed (both at 23.5%). This is understandable since adolescence is an age where patients are overly conscious of their body image, and when the body has changed and bears unsightly skin marks, one can truly feel diminished compared to his or her peers.

There were also more adults who were diminished (48.9%) than depressed (31.7%) or anxious (19.5%). There were fewer anxious adults. The reasons listed above could explain why there were more adults feeling diminished than depressed or anxious. Overall, looking at the three categories of patients who answered the questionnaire, there were more patients feeling diminished. This could be due to the debilitating consequences of BU and heavy financial costs related to its treatment and care, which sometimes ruined these former patients. There is a difference between adults and adolescents, in fact adults were more depressed and adolescents more anxious. For adolescents, the issue of a professional future is at stake, thus their growing anxiety. But when an elderly patient is anxious there can be many reasons. For adults, the issue of rebuilding their life and getting back to work can trigger depression.

BU is a disease requiring a constraining treatment and lingering physical consequences after the cure, it induces a growing poverty and psychological regression requiring the permanent help of family members. These elements show that a systematic psychotherapy should be proposed as part of the care management of these patients during their hospitalization and once they have returned home. On a professional level, 81% of workers ( n = 68) went back to work; out of patients who returned to work, 75% of them ( n = 51) went back to the same job and 25% ( n = 17) changed jobs. After being cured of the disease, patients had to face their obligations. Beninese people really pride themselves in being independent; this could explain the high percentage of former patients returning to work, furthermore 75% kept the same job due to foreseeable difficulties in changing jobs. The fear of not being able to succeed in a new job for which they received no training combined to the attachment to their old job could explain this high rate. Impairments and limitation of participation, both consequences of BU, were not enough to affect the motivation of these dedicated hard workers. The 25% of former patients, who had to change jobs, did it for two reasons:

- •

the first was functional impairments and limitation of participation. These patients wanted to work despite their impairments, which were not as severe as other patients;

- •

the second reason was that their previous job required being in contact with water and thus there was a risk of BU recurrence. These patients had to stop their professional activities and change jobs, often for lesser money but their new activity was better suited to their new lives.

The psychological experience of dealing with BU had a statistically significant impact on the socioprofessional and family life of former patients ( P < 0.05) ( Table 2 ).

For the 19% of patients who did not get back to work, reasons stated were: impaired capacities in 13.1% ( n = 11) of cases, pain and lack of support in 5.9% ( n = 5) of cases.

These results show the lack of a real politic for social and professional reinsertion in our country. According to Autier in a context of endemic unemployment, the reinsertion of persons with reduced capacities for work and heavy efforts, because of long-lasting health issues or consequences, can seem quite risky.

Regarding education, 90.1% of students in school/high school/university went back to school and 29.4% ( n = 40) had a normal academic progression, 45.6% ( n = 62) lost 1 year, 17.6% ( n = 24) lost 2 years and 7.4% ( n = 10) lost at least 3 years. We saw then that 70.6% of children lost at least one school or university year. These results could be explained by the following reasons:

- •

children and students frequently missed class because of the antibiotics therapy lasting at least 8 weeks and bandages care;

- •

hospitalization duration (at least 3 months), surgery and functional rehabilitation required time away from school.

We expected the number of children with lost school years to be less, because of several BU medical care centers in each endemic zone. Yet, there is hope since 29.4% of these school children and students had a normal academic progression thanks to early screening and care management next to their homes.

Upon getting back, 63.2% of school children were well accepted by their schoolmates ( Table 4 ). This result shows the real solidarity of the African people. The 36.8% of rejected patients could be explained by the young age of these schoolmates, fear of being infected when playing with cured children because of the unsightly and voluminous scar, a common consequence of BU. Some efforts still need to be made to ensure proper social and school reinsertion of these children. There is a real impact of schoolmates’ acceptance on the academic progression of former BU patients with a statistically significant difference ( P = 0.001). For the 9.9% of patients in school who did not go back to school or university, the two main reasons were: firstly, impaired capacities and lack of support and, secondly, fear of BU recurrence. Some children had to cross a river to get to school and others feared getting injured during recess. In order to address the very important issue of academic delays, in 2007 a primary school was built within the Allada CDTUB. However, the proportion of children who fell back at least a year remains quite important. The most determinant factors seem to be negligence from patients and/or family members, lack of information and absence of synergy between sanitary and school activities. Stienstra et al. in a study on BU patients who did not benefit from physical rehabilitation, reported that being a woman, older age, joint affections, lesions on the lower limbs were all factors influencing functional impairments and financial restrictions, the latter being at the root of work and school difficulties. On a family level, 3.3% of patients ( n = 8) got married after being cured from the disease. These patients were in the right age range to get married. Consequences of BU, i.e. unsightly scars, limitation of capacities and restricted participation did not prevent these patients from getting married. This shows that love is stronger than disability and/or physical scars. However, one patient (0.4%) was abandoned by her husband and experienced a divorced after the disease. The first cause of this reject was the prolonged absence due to repeated hospital stays; the second reason was related to the severe impairments and limited range of motions lingering for this patient. Furthermore, 31.6% of patients could not fully assume their role as a spouse, parent or children, psychological experience was the most influencing factor ( P = 0.008). Restricted abilities and participation limitations were the first causes in addition to late postoperative pain.

Similar observations led Phanzu et al. into thinking that in spite of encouraging results, it was essential to implement new strategies to improve the fight against BU for patients living in precarious conditions.

1.5

Conclusion

The physical consequences of BU for cured patients once they get home bear heavy psychological, social, professional and family repercussions. It is urgent to implement a well-structured psychosocioprofessional reinsertion program, with a large part devoted to psychotherapy, in order to offer a proper follow-up for these former patients in their home environment.

Further studies will be able to refine the necessary parameters for a real ecological rehabilitation of these former patients.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’ulcère de Buruli (UB) est une maladie émergente due au Mycobacterium ulcerans (Mu). Il sévit sous forme de foyers endémiques en zone intertropicale (Afrique, Amérique, Asie et Océanie ). Bien que l’UB n’entraîne qu’un faible taux de mortalité, le véritable problème vient des restrictions de capacités et des limitations de participation qu’il provoque dans 25 % des cas selon l’OMS . Ces incapacités et handicaps persistent à des degrés divers chez des patients déclarés guéris d’UB même avec l’introduction de la rééducation dans l’arsenal thérapeutique . Le problème de la gestion de leur invalidité au sein de leur milieu d’origine se pose et aucune étude ne s’y est intéressée depuis que la rééducation a été reconnue comme pilier incontournable du traitement de l’UB. Cette étude examine le devenir psychosocioprofessionnel et familial des patients guéris d’UB après leur retour à domicile.

2.2

Patients et méthode d’étude

2.2.1

Patients

La population d’étude a été constituée des patients atteints d’UB traités, suivis et déclarés guéris au Centre de dépistage et de traitement de l’ulcère de Buruli (CDTUB) d’Allada de 2005 à 2009. Tous les patients remplissant les critères énumérés ci-dessous ont été enrôlés dans l’étude.

2.2.1.1

Critères d’inclusion

Les patients qui ont été dépistés, pris en charge et sont déclarés guéris au CDTUB d’Allada de janvier 2005 à décembre 2009.

Les patients dont la base de données du CDTUB renseigne sur leurs adresses et/ou qui ont été identifiés par les relais communautaires.

Les anciens patients UB qui ont résidé au Bénin dans un rayon de 100 km au plus du CDTUB d’Allada (zone d’influence ou aire géographique du CDTUB d’Allada) au cours de l’étude.

2.2.1.2

Critères de non-inclusion

Tous les cas de rechute d’UB.

Tous les patients qui ont eu des antécédents capables de modifier leur devenir psychosocioprofessionnel et familial (HTA, diabète, pathologie psychiatrique et fracture d’un os du membre touché).

2.2.2

Méthode d’étude

2.2.2.1

Type d’étude

Il s’agit d’une étude transversale et descriptive et analytique qui s’est déroulée de janvier à juillet 2010 dans l’aire géographique du CDTUB d’Allada, dans le département de l’Atlantique au Bénin. Nous entendons par aire géographie, la région située dans un rayon de 100 km autour du centre auquel sont référés les patients.

2.2.2.2

Déroulement

À partir de la base de données obtenue au CDTUB d’Allada, nous avons répertorié 347 malades suivis et déclarés guéris pendant la période de janvier 2005 à décembre 2009. Aidés par les relais communautaires de l’UB qui sont restés au contact des malades depuis plusieurs années, motif de la confiance et de l’acceptation à participer à l’étude, et généralement sur rendez-vous, les patients remplissant les critères sus-cités sont revus à leurs domiciles. C’est ainsi que 244 patients ont pu être revus et ont constitué la population d’étude. Des 103 patients restants, 20 sont perdus de vue par les relais communautaires, 22 sont allés travailler au Nigéria, 30 sont des enfants en âge préscolaire et qui n’ont pas pu répondre aux questions, 18 ont toujours été absents malgré un rendez-vous négocié et accepté. Ce qui est considéré comme un refus de participer à l’étude et enfin 13 sont décédés pour diverses causes.

À leur domicile, ces anciens patients ont été soumis à un questionnaire et à un examen clinique. Le questionnaire explore leur vécu psychosocioprofessionnel et familial par des réponses fermées ou ouvertes aux différentes questions posées. Concernant spécifiquement le vécu psychologique, nous avons utilisé l’échelle de Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) de Sigmond Snaith. Lorsque la somme des points pour l’anxiété et/ou dépression est inférieure à 10, pas d’anxiété ni de dépression ; mais lorsqu’elle est supérieure à 10, il y a anxiété et/ou dépression dans l’un ou l’autre cas. Ce qui nous a permis de distinguer ceux qui sont déprimés des anxieux. Enfin, dans le questionnaire auquel sont soumis les patients adolescents, adultes et ceux du troisième âge, il leur était demandé s’ils se sentaient diminués vis-à-vis de leurs semblables. Ce qui a permis de retrouver les diminués.

2.2.2.3

Variables d’étude

Les variables d’étude sont :

- •

vécu psychologique de la maladie par le patient ;

- •

vécu de l’hospitalisation ;

- •

acceptation familiale ;

- •

impact de la maladie sur les activités professionnelles ;

- •

impact de la maladie sur la scolarité des enfants ;

- •

comportement des camarades de classe après la reprise ;

- •

rejet des enfants par leurs camarades s’exprimant par les exclusions au cours des jeux et des insultes ;

- •

impact de la maladie sur l’apprentissage ;

- •

impact de la maladie sur la vie familiale.

2.2.2.4

Traitement et analyse des données

La masse de données après l’enquête à été saisie dans le logiciel Microsoft office Excel 2007. L’analyse statistique a été faite par le logiciel EPI info version 3.4.3. Les graphiques ont été élaborés dans Microsoft office Excel 2007. Le test de Chi 2 et le test statistique de Fischer ont été utilisés ; la différence est statistiquement significative lorsque p < 0,05.

2.2.2.5

Considérations éthiques

Cette enquête a eu l’autorisation du Programme national de lutte contre la lèpre et l’ulcère de Buruli (PNLLUB). Ce qui représente la caution en matière d’éthique dans ces genres de travaux au moment de l’étude. Les informations sont recueillies après le consentement éclairé oral des patients et/ou de leurs parents. Tout au long de l’étude, nous avons observé le respect strict et rigoureux de l’anonymat, de la confidentialité et du secret médical.

2.2.2.6

Conflit d’intérêt

Il n’y avait pas de notion de conflit d’intérêt lié à cet article.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Données démographiques

2.3.1.1

Âge

L’âge moyen des patients de notre étude a été de huit ans. Les enfants de moins de 15 ans ont été les plus nombreux avec 57 % ( n = 139) ; les personnes de troisième âge les moins représentées (0,81 %, n = 2) ; les extrêmes étant de six et 89 ans. La Fig. 1 illustre leur répartition selon les tranches d’âge.