Posterior Pelvic-Ring Disruptions: Iliosacral Screws

M.L. Chip Routt Jr.

Indications/Contraindications

Iliosacral screw fixation is indicated for selected unstable fractures of the posterior pelvic ring including sacroiliac (SI) joint dislocations; sacral fractures; certain, posterior, iliac “crescent” fracture-SI disruptions; and combinations of these injuries. This technique can be used alone or in conjunction with other forms of pelvic internal or external fixation. The timing of internal fixation for displaced pelvic-ring injuries depends on numerous factors such as the fracture pattern, local skin condition, hemodynamic status, patient age and body habitus, and abdominal or urologic injuries.

The surgeon must meet certain criteria to insert iliosacral screws safely. The surgeon must completely understand normal posterior-pelvic anatomy, as well as its variations, especially the upper-sacral structure. High-quality fluoroscopic imaging of the entire pelvis must be available during surgery. The surgeon must completely understand the specific injury and the displacement patterns of the posterior pelvic ring and be able to correlate normal and altered pelvic pathologic conditions as seen on radiographic images. Based on the preoperative plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis, the surgeon must be confident that the patient’s upper-sacral anatomy will allow safe screw placement. Finally, the surgeon must possess the technical skill to reduce the posterior pelvic deformity accurately by closed or open techniques. Iliosacral screws should not be used unless the injured area is reduced.

Dysmorphism of the upper sacrum is a relative contraindication for insertion of iliosacral screws. The dysmorphic upper sacrum is a common anatomical variant that decreases the upper-sacral, alar, osseous area available for safe screw passage into the sacral body. Because of the complex anatomy of the pelvis, dysmorphic sacral segments can be difficult to identify predictably during surgery. Upper-sacral-segment abnormalities occur in 30% to 40% of patients and are best identified on the outlet radiograph and CT scans of the pelvis. These abnormalities are most often symmetrical but are unilateral

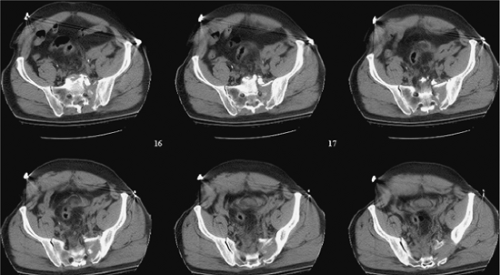

in some patients. The radiographic outlet-image hallmarks of upper-sacral-segment dysmorphism include the following: (a) the lumbosacral disc space is colinear with the iliac crests, (b) the ventral foramen of the upper-sacral nerve root is not circular in appearance, (c) residual disc space is noted between the upper and second sacral segments; (d) the dysmorphic ala decline acutely from the upper-sacral body to the SI joints; and (e) mammillary processes are present on the dysmorphic ala. On the CT scan of the pelvis, sacral dysmorphism is noted by accentuated, undulating, SI surfaces; an obliquely oriented, anterior, alar cortex relative to the iliac cortical density (ICD); and a narrowed alar zone available for screw insertion (Fig. 39.1).

in some patients. The radiographic outlet-image hallmarks of upper-sacral-segment dysmorphism include the following: (a) the lumbosacral disc space is colinear with the iliac crests, (b) the ventral foramen of the upper-sacral nerve root is not circular in appearance, (c) residual disc space is noted between the upper and second sacral segments; (d) the dysmorphic ala decline acutely from the upper-sacral body to the SI joints; and (e) mammillary processes are present on the dysmorphic ala. On the CT scan of the pelvis, sacral dysmorphism is noted by accentuated, undulating, SI surfaces; an obliquely oriented, anterior, alar cortex relative to the iliac cortical density (ICD); and a narrowed alar zone available for screw insertion (Fig. 39.1).

Obesity is a relative contraindication to iliosacral screw fixation for several reasons. Intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging in obese patients is compromised by the excessive abdominal panniculus, which may obstruct inlet and outlet images of the pelvis. Lateral pelvic-flank obesity limits true lateral sacral imaging. Fluoroscopic detail in obese patients may be inadequate for safe guide-screw placement. In addition, extra long instruments such as drills, taps, and screwdrivers are necessary for treating the obese patient.

Fluoroscopic imaging of the pelvis is also complicated in some polytraumatized patients because of contrast agents that were used during the initial abdominal evaluations. Therefore, it should be avoided when possible. In patients with open fractures or compromised posterior skin and soft tissues, iliosacral screw placement should be done percutaneously when possible, rather than through an open approach. In a common mistake, the surgeon enters and inadvertently decompresses a pelvic degloving injury during the process of iliosacral screw insertion. In such situations, the screw is inserted, the degloving area irrigated and debrided, and the dead space closed over suction drains. In severe cases, the dead space is packed open (Fig. 39.2).

Preoperative Planning

In the hemodynamically unstable patient with an unstable pelvic-ring injury, resuscitation using advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality rates. Large-bore intravenous access allows rapid volume infusion, and the patient is kept warm. The potentially injured pelvis can be immobilized at the accident scene before patient transport through use of a variety of simple techniques. A vacuum beanbag, a large circumferential sheet, and military antishock trousers (MAST) are recommended for temporary stabilization of the pelvis. Pelvic wrapping devices are also commercially available but are costly, and they often add to an overloaded inventory. Sheets are readily available, inexpensive, and can be adjusted in width to fit any body habitus. They can be reused or discarded, require no additional inventory, and can be positioned or trimmed to allow groin, perineal, flank, abdominal, or combination access for other resuscitation or evaluation procedures. Regardless of the technique chosen, pelvic overcompression should be avoided.

The physical examination is a single mechanical and visual evaluation performed by the most experienced physician and then communicated to the rest of the treatment team. A detailed neurologic examination is documented in alert patients. During the examination of the pelvic area, the surgeon identifies abrasions, contusions, degloving injuries, or open wounds. Sterile pressure dressings are applied to open pelvic wounds to diminish ongoing bleeding. The lumbosacral palpation and visual, along with the digital rectal, examinations are performed during the posterior spine assessment after the patient has been log rolled by a team of assistants. The mechanical evaluation of the pelvis is ideally performed under fluoroscopic imaging. Pelvic ring instability is noted as gentle manual pressure is applied simultaneously toward the midline on each iliac crest. This maneuver produces significant pain in alert patients with pelvic ring instability, iliac fractures, and certain acetabular fractures. Local pain during iliac manual compression can also be due to iliac area contusions in the absence of pelvic-ring osseous injury. To prevent fracture-surface clot disruptions (among other potential consequences), vigorous and repetitive, manual, pelvic examinations are not recommended. Digital rectal, prostatic, and vaginal examinations are performed to test for both

gross and occult blood. The vaginal and rectal exams are initially done with the patient supine or log rolled into the lateral position. A more thorough speculum vaginal exam is deferred until pelvic stability is achieved so the patient can be placed safely in the lithotomy position.

gross and occult blood. The vaginal and rectal exams are initially done with the patient supine or log rolled into the lateral position. A more thorough speculum vaginal exam is deferred until pelvic stability is achieved so the patient can be placed safely in the lithotomy position.

The radiographic assessment begins with a screening, anteroposterior (AP), plain radiograph of the pelvis. A complete radiographic series includes orthogonal views (inlet/outlet), and a lateral sacral image should be obtained especially in patients whose screening AP films show a “paradoxical inlet” of the upper-sacral area. A CT scan of the pelvis is essential to further delineate the fracture anatomy. The CT scan images of the pelvis indicate the patient’s body habitus, reveal related soft-tissue abnormalities, such as hematoma, as well as degloving injuries and their extent, and also show contrast extrusions reflecting bladder, vascular, or other injuries. The pelvic CT images also show the lumbosacral nerve-root positions as well as sacral alar fractures. The iliac vessels and their relationship with displaced, superior-pubic ramus fractures are often seen clearly on the images. With similar clarity, displaced inferior-ramus fractures can be identified as they intrude on the vagina or are displaced anteriorly. The CT scan details subtle osseous injuries missed on the plain films and shows the hemipelvic displacement patterns. An ipsilateral pneumothorax can often be seen on CT scans of the pelvis because the subcutaneous air extends to the iliac area.

The timing of pelvic reduction and fixation is primarily dependent on the clinical condition of the patient, institutional capabilities, and surgeon availability and expertise. Hemodynamically unstable patients with unstable pelvic-ring injuries require some form of rapid pelvic stabilization. Anterior-pelvic external-fixation frames and posterior-pelvic antishock clamps have been advocated to stabilize the pelvic ring rapidly. When possible, the pelvic external-fixation system is applied through use of iliac crest pins inserted after a closed reduction is obtained and maintained by the circumferential pelvic wrap. Access holes are cut in the sheet overlying the iliac crest. The skin is prepped and the pins inserted between the iliac cortical tables. We recommend application of such devices using the fluoroscopy unit in the angiographic suite when possible. The circumferential wrap can also be adjusted through use of the same imaging unit to assess and adjust the pelvic closed-manipulation reduction. If the reduction has been achieved, iliosacral screws can also be inserted using access portals in the sheet (Fig. 39.3). In selected hemodynamically unstable patients, pelvic angiographic embolization is helpful in controlling pelvic arterial bleeding.

Emergency, pelvic, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) induces the risk of bleeding and has a higher complication rate, but for certain patients and injury patterns, the benefits may outweigh the risks. Percutaneous, posterior-pelvic, internal fixation through use of iliosacral screws minimizes the bleeding risk, is quick, and is useful when an accurate closed-manipulated reduction of the posterior pelvic-ring injury can be accomplished. Percutaneous iliosacral screws may be used in emergency resuscitation situations in combination with standard anterior-pelvic external fixation. In patients who are hemodynamically stable, operative pelvic stabilization should be done early. Before surgery, distal femoral traction improves the reduction and provides patient comfort.

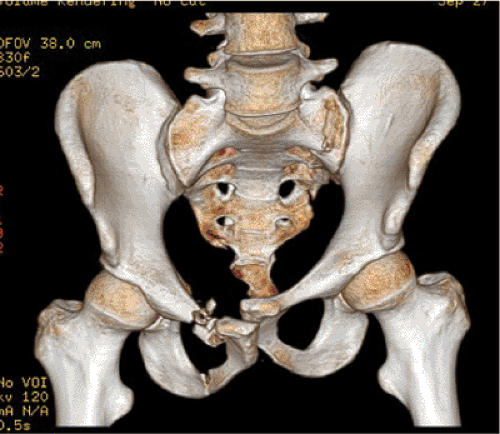

During the preoperative planning phase, the surgeon should consider the mechanism of injury, associated major-system injuries, and the local soft-tissue conditions. Special attention is given to an analysis of the plain films and CT scans. On occasion, iliac and obturator oblique radiographs of the pelvis are obtained in patients with concomitant acetabular fractures. A two-dimensional CT scan further delineates the specific sites of injury and direction of displacement (Fig. 39.4). Just as important as detailing the injury and local anatomy, the two-dimensional CT scan also is used preoperatively to determine the number of screws that can be inserted, the upper-sacral anatomy, the planned starting point on the lateral ilium, and the screw direction and length needed to achieve stable and balanced fixation (Fig. 39.5). Some clinicians prefer three-dimensional CT scans to improve their understanding of the fracture details and deformity patterns (Fig. 39.6).

Based on the mechanism of injury, the physical examination, and the radiographic studies, the surgeon formulates a plan. The preoperative plan includes all of the surgical details including timing, patient positioning, exposures, reduction strategies, clamp application sites, fixation techniques, and treatment alternatives. Even the anticipated rehabilitation goals are planned preoperatively; they are especially important for polytraumatized patients.

Not all posterior pelvic fractures are amenable to iliosacral screw fixation, and the surgeon should be familiar with various anterior-pelvic and posterior-pelvic operative

exposures and fixation techniques as well as percutaneous reduction and fixation strategies. The treatment plan must be tailored to the individual patient. Insertion of iliosacral screws can be performed with the patient in the supine, lateral, or prone position; each patient position has advantages and disadvantages. The lateral position complicates both anterior-pelvic and posterior-pelvic surgical exposures and is not recommended for patients with potential spinal injuries. Prone positioning allows posterior surgical exposures but denies the surgeon simultaneous anterior-pelvic surgical access. Anterior-pelvic external-fixation frames further complicate prone and lateral patient positioning for surgery.

exposures and fixation techniques as well as percutaneous reduction and fixation strategies. The treatment plan must be tailored to the individual patient. Insertion of iliosacral screws can be performed with the patient in the supine, lateral, or prone position; each patient position has advantages and disadvantages. The lateral position complicates both anterior-pelvic and posterior-pelvic surgical exposures and is not recommended for patients with potential spinal injuries. Prone positioning allows posterior surgical exposures but denies the surgeon simultaneous anterior-pelvic surgical access. Anterior-pelvic external-fixation frames further complicate prone and lateral patient positioning for surgery.

If the supine position is selected, strict attention to detail during patient positioning, as well as skin preparation and draping, is mandatory. In polytraumatized patients, the supine position is familiar, allows several teams to work simultaneously on injured extremities, and also provides anterior pelvic access. With this approach, patient position adjustments and repeated drapings are avoided; thus valuable time is saved.

Computer guidance systems have become available and, like neurodiagnostic monitoring, are intended to simplify the procedure by making it safer. Computer navigation systems are not a substitute for the surgeon’s thorough knowledge of the sacral anatomy and radiology. Current navigation systems do not accommodate fracture displacements that can occur between the time of the preoperative CT scan and the intraoperative navigation. Early results have shown that navigation systems for iliosacral screw insertion may decrease the use of fluoroscopy but not overall surgical time.

Surgery