Postcapsulorrhaphy Arthroplasty

John W. Sperling

Robert H. Cofield

INTRODUCTION

Postcapsulorrhaphy arthritis is defined as glenohumeral arthritis following prior instability procedures. For the purposes of this chapter, postcapsulorrhaphy does not include patients who developed arthritis because of dislocations in the absence of surgery. Additionally, it does not include patients who have developed arthritis as a result of intraarticular instrumentation. The latter two groups of patients do not necessarily have the clinical characteristics that define postcapsulorrhaphy, such as a significant internal rotation contracture.

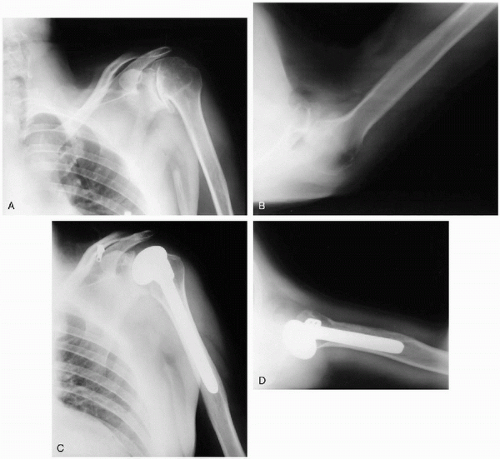

The development of glenohumeral arthritis is a well-recognized complication of instability surgery (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of postcapsulorrhaphy arthritis has several potential challenges, including soft-tissue imbalance, potential bone deficiency, and the young age of the patients (Fig. 10-1).

Whereas there have been numerous reports concerning the results of shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis, there is little published information on postcapsulorrhaphy arthroplasty. There have been few reports describing the problems encountered, the techniques to address the distorted anatomy, or the outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty in this setting.

To treat the patient who develops arthritis after instability surgery, the surgeon requires information in six areas. These include the following: (a) an understanding of the instability pattern that led to the stabilization procedure, (b) details of the stabilization surgery, (c) understanding the current situation in the shoulder, (d) understanding the patient’s occupational and recreational needs, (e) compiling the treatment options and planning the technical details of the arthroplasty, and (f) recognizing the benefits and limitations of the procedure.

A review of the previously mentioned areas will allow the surgeon insight into the special problems encountered with patients who have had prior instability surgery. This

chapter will outline the pathologic surgical anatomy, evaluation of the patient, treatment planning, surgical technique, and literature review that address postcapsulorrhaphy arthroplasty.

chapter will outline the pathologic surgical anatomy, evaluation of the patient, treatment planning, surgical technique, and literature review that address postcapsulorrhaphy arthroplasty.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

Many previously popular stabilization procedures are no longer used to treat shoulder instability. Certain questions should be answered in regard to the procedure that was previously performed. Was the procedure an anatomic or nonanatomic procedure? Was the instability repair a soft-tissue procedure only, or was there alteration of osseous anatomy?

Typically, there is anterior soft-tissue contracture with subsequent posterior subluxation (Fig. 10-2A-2D). Theoretically, the reverse may be present with a prior posterior repair, but it is very uncommon. Posterior glenoid erosion is also frequently present. The rotator cuff is usually intact in these patients but is often distorted in association with shoulder subluxation and contractures.

EVALUATION

A careful history will allow the surgeon to determine the indication for the stabilization procedure, the type of procedure performed, and whether recurrent instability was present. Obtaining prior operative reports facilitates the operative procedure by giving insight into the altered anatomy present. One needs to determine the patient’s primary complaint: is it pain, weakness, or loss of motion? This needs to be placed in context of the patient’s current and future demands on the shoulder.

A systematic examination of the shoulder, the extremity, and the cervical spine should be performed. Examination includes careful strength, motion, and stability testing.

Plain radiographs of the shoulder include at minimum a 40-degree posterior oblique view in internal and external rotation plus an axillary view. A computed tomography (CT) scan can be helpful for preoperative planning. This allows further assessment of glenoid erosion and version. Among those with decreased strength, a magnetic resonance imaging scan or an electromyography may be performed to detect a rotator cuff tear or subtle neurologic abnormalities.

There should be consideration of adjunctive tests, such as a white blood cell count with differential, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for those patients with implants or a question of infection. Additionally, one could consider paired bone and indiumlabeled white-cell radioisotope scans to further exclude the possibility of a low-grade infection. If the suspicion of infection is higher, a shoulder arthrogram and aspiration are obtained.

With the aforementioned information supplemented by adjunctive tests as necessary, one can then better define the soft-tissue and bone abnormalities and then proceed with the next step—treatment planning.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS

The patient-based indication for shoulder arthroplasty is severe shoulder pain that has failed to respond to nonoperative measures, including antiinflammatory medications, gentle therapy, and consideration of a cortisone injection. Considerable stiffness may also be present. From a structural standpoint, there is a loss of glenohumeral cartilage with bone-against-bone contact in the joint.

Patients with postcapsulorrhaphy arthropathy are often younger than patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty for other types of arthritis. More importantly, their activity levels, postoperative functional demands, and life expectancies are higher than would be considered ideal for most arthroplasty procedures. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to all of these variables when deciding between arthroplasty and other options in the management of patients with postcapsulorrhaphy arthritis.

TREATMENT PLANNING

Because of the frequently distorted soft-tissue and osseous anatomy, it is useful to develop a treatment plan or a problem

list starting with the exposure and soft-tissue releases required. For example, if glenoid deficiency is present, some form of bone graft should be planned for—either autograft or allograft. Patients with a prior history of anterior instability surgery may have subscapularis deficiency. Therefore, the surgeon should recognize this and plan for subscapularis reconstruction, tendon transfer, or soft-tissue allograft. Patients with combined bone deficiency and soft-tissue deficiency may be handled with an Achilles tendon allograft with the calcaneus attached. Finally, one must plan for the potential need for nonstandard implants or a variety of component sizes that are not usually available.

list starting with the exposure and soft-tissue releases required. For example, if glenoid deficiency is present, some form of bone graft should be planned for—either autograft or allograft. Patients with a prior history of anterior instability surgery may have subscapularis deficiency. Therefore, the surgeon should recognize this and plan for subscapularis reconstruction, tendon transfer, or soft-tissue allograft. Patients with combined bone deficiency and soft-tissue deficiency may be handled with an Achilles tendon allograft with the calcaneus attached. Finally, one must plan for the potential need for nonstandard implants or a variety of component sizes that are not usually available.

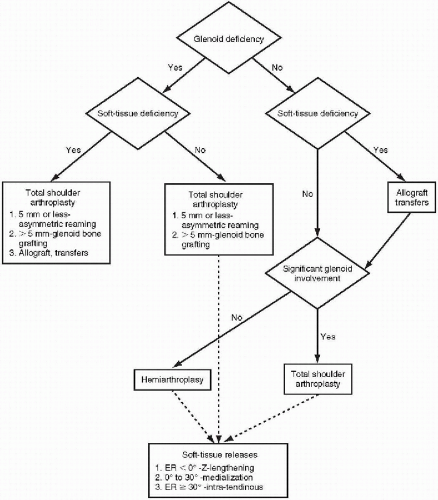

An algorithmic approach to treatment planning is helpful. If preoperative evaluation indicates no bone or soft-tissue deficiency, standard arthroplasty may be performed. The use of a glenoid component is dictated by the degree of glenoid involvement, age, and activity level. If glenoid bone loss is present, glenoid replacement is more likely to be necessary. The bone loss is addressed through a combination of asymmetric glenoid reaming and augmentation (i.e., bone graft). Soft-tissue deficiency is managed through the use of tendon transfers or allograft reconstruction. Residual instability following placement of the components is addressed through a combination of changing

component selection and capsular plication. Figure 10-3 summarizes this treatment algorithm and should only be thought of as a guideline for the management of postcapsulorrhaphy arthropathy.

component selection and capsular plication. Figure 10-3 summarizes this treatment algorithm and should only be thought of as a guideline for the management of postcapsulorrhaphy arthropathy.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Approach

The standard approach will take place through the deltopectoral interval. The skin incision is placed over the anterior aspect of the shoulder, slightly lateral to the deltopectoral interval. In the setting of prior surgery, such as the case with postcapsulorrhaphy arthritis, there are one or more preceding surgical incisions. There is an attempt to use the prior incision or to incorporate it into a longer incision to approach the deltopectoral interval. Among those with a broad scar, the widened area is excised. Development of the deltopectoral interval is most easily performed just distal to the clavicle where there is a natural infraclavicular triangle separating the deltoid and pectoralis major. The exposure then continues distally. The deltoid is retracted, leaving the cephalic vein medially. The cephalic vein may have been previously ligated or incorporated in scar.

Mobilization of the deltoid from the clavicle to its humeral insertion is performed. Frequently, the anterior portion of the deltoid insertion is elevated slightly, in continuity with the more distal periosteum of the humerus. The deltoid is held laterally with a Brown-like deltoid retractor.

On the medial aspect of the shoulder, the plane between the conjoined tendon and the subscapularis is developed. Frequently, significant scar is present in this plane. Dissection can be facilitated by placing the arm in maximum external rotation. Typically, there is less scar just distal to the coracoid. Dissection then progresses from superior to inferior and from lateral to medial to develop this interval. Clearly, careful dissection in this area is necessary because of the close proximity to the neurovascular group, the axillary nerve, and the musculocutaneous nerve. As such, meticulous dissection may take a few minutes, or it may take considerable time to free the subscapularis. Please note that nerves to the subscapularis should be preserved. They are typically 1.5 cm or more medial to the glenoid rim or the medial border of the conjoined tendon group (9). Next, release of scar from around the base of the coracoid is accomplished, and the shoulder range of motion is tested.

The inferior portion of the rotator interval is incised with great care to avoid injury to the long head of biceps tendon. The thickness of the anterior shoulder capsule and subscapularis can then be assessed by having access to both internal and external surfaces. If there is less than 0 degrees of passive external rotation and these structures are thickened, consideration can be given to “open book” or z-lengthening of the subscapularis and anterior shoulder capsule. Z-lengthening is most commonly done. This is accomplished by elevating the outermost two-thirds of the subscapularis tendon from bone of the humerus and leaving the deeper one-third and the thickened anterior shoulder capsule intact. One then continues to dissect medially in this layer until the glenoid rim is reached. An incision is then made through the remaining subscapularis tendon and anterior shoulder capsule (Fig. 10-4A-B). This will usually result in 1.5 or 2 cm of additional length to the anterior shoulder structures.

Alternatively, the “open book” technique is accomplished by elevating the subscapularis and thickened anterior shoulder capsule from the proximal humerus as a single layer. After the capsule and subscapularis have been reflected medially, the capsule is then released from the glenoid. The interval between the medial capsule and the subscapularis muscle belly is then dissected from medial to lateral in the mid substance of the conjoined structures, stopping short of the final centimeter of their junction. The medial portion of the anterior capsule is then turned laterally to effect the lengthening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree