Plate Fixation of Humeral Shaft Fractures

Matthew J. Garberina

Charles L. Getz

DEFINITION

Humeral shaft fractures, which account for about 3% of adult fractures, usually result from a direct blow or indirect twisting injury to the brachium.

These injuries are most commonly treated nonoperatively with a prefabricated fracture brace. The humerus is the most freely movable long bone, and anatomic reduction is not required.

Patients often can tolerate up to 20 degrees of anterior angulation, 30 degrees of varus angulation, and 3 cm of shortening without significant functional loss.

There are, however, several indications for surgical treatment of humeral shaft fractures:

Open fracture

Bilateral humeral shaft fractures or polytrauma; floating elbow

Segmental fracture

Inability to maintain acceptable alignment with closed treatment (ie, angulation >20 degrees, complete or near complete fracture displacement with lack of bony contact)—seen more commonly with transverse fractures (FIG 1)

Humeral shaft nonunion

Pathologic fractures

Arterial or brachial plexus injury

Open reduction with internal plate fixation requires extensive dissection and operative skill. However, it offers advantages over intramedullary fixation because the rotator cuff is not violated, which leads to improved postoperative shoulder function.3

ANATOMY

The humeral shaft is defined using key landmarks: the area between the upper margin of the pectoralis major tendon and the supracondylar ridge.5

The blood supply of the humeral shaft comes from the posterior humeral circumflex vessels and branches of the brachial and profunda brachial arteries.

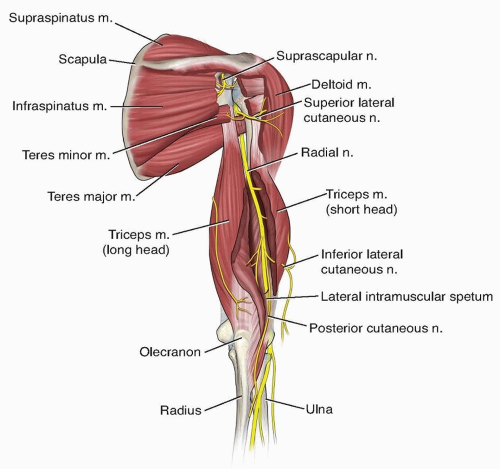

The radial nerve and profunda brachial artery pass through the triangular interval (bordered superiorly by the teres major, medially by the medial head of the triceps, and laterally by the humeral shaft). The nerve then transverses from medial to lateral behind the humeral shaft and travels distally to a location between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles (FIG 2).

The musculocutaneous nerve lies on the undersurface of the biceps muscle and terminates distally as the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

The humeral shaft has anteromedial, anterolateral, and posterior surfaces. Proximal and midshaft fractures are more amenable to plating on the anterolateral surface, whereas distal fractures often require posterior plate fixation.

PATHOGENESIS

Humeral shaft fractures occur after both direct and indirect injuries. Direct blows to the brachium can fracture the humeral shaft in a transverse pattern, often with a butterfly fragment. Injuries with high degrees of energy often result in a greater degree of fracture comminution.

Indirect injuries, such as those that can occur with activities such as arm wrestling, often involve a twisting mechanism and result in a spiral fracture pattern. Higher energy injuries may result in muscle interposition between the fracture fragments, which can inhibit reduction and healing.

A study of 240 humeral shaft fractures revealed radial nerve palsies in 42 patients, for an overall rate of 18% (17% in closed injuries). Fractures in the midshaft were more likely to have concomitant radial nerve palsy. Twenty five of these patients had complete recovery in a range of 1 day to 10 months. Ten patients did not have radial nerve recovery. Median and ulnar nerve palsies were seen very rarely in patients with open fractures.7

Concomitant vascular injuries are present in about 3% of patients with humeral shaft fractures.

NATURAL HISTORY

Most humeral shaft fractures heal with nonoperative management. The most common treatment method is initial splinting from shoulder to wrist, followed by application of a prefabricated fracture brace when the patient is comfortable, usually within 2 weeks of the injury.

Studies by Sarmiento and coauthors10, 11 have shown the effectiveness of functional bracing in the treatment of humeral shaft fractures. Nonunion rates with this method of treatment are in the 4% range, lower than seen when treating with external fixators, plates, or intramedullary nails.

Closed fractures with initial radial nerve palsy can be observed, with expected recovery over a period of 3 to 6 months. Late-developing radial nerve palsies require surgical exploration.

Angulation of the humeral shaft after fracture healing is expected and is well tolerated when it is less than 20 degrees. Varus deformity is most common.10

Adjacent joint stiffness of the shoulder and elbow also is common. If the situation dictates treatment, physical therapy reliably restores joint motion in these patients.

Relative contraindications to closed treatment include bilateral humeral shaft fractures or patients with polytrauma who require an intact brachium to ambulate. Transverse fractures and those with significant muscle imposition also are more amenable to operative fixation.11

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The examining physician must perform a complete examination of the affected limb to rule out concomitant injuries.

The skin should be thoroughly evaluated for evidence of an open fracture. This includes examination of the axilla. Entry and exit wounds are sought in gunshot victims. Swelling is common, and the patient may have an obvious deformity.

The patient often braces the affected limb to his or her side, making evaluation of shoulder and elbow range of motion difficult. Bony prominences should be gently palpated to evaluate for other injuries, such as an olecranon fracture.

Evaluate the appearance and skeletal stability of the forearm to rule out the presence of a coexisting both-bone forearm fracture (“floating elbow”). This finding necessitates operative fixation of humeral, radial, and ulnar fractures.

Determine the vascular status of the upper extremity by palpating the radial and ulnar pulses at the wrist. Compare these findings with the unaffected limb. Selected cases may require Doppler arterial examination.2

A complete neurologic assessment is necessary, with particular attention focused on the status of the radial nerve. This structure is at risk proximally, as it passes posteriorly to the humeral shaft after emerging from the triangular interval, as well as distally, as it lies adjacent to the supracondylar ridge (near the location of the Holstein-Lewis distal one-third spiral humeral shaft fracture).

Examine sensory function in the first dorsal web space, wrist extension, and thumb interphalangeal joint extension to determine the functional status of the radial nerve.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

At least two plain radiographs at 90-degree angles to each other are necessary to evaluate the displacement, shortening, and comminution of the humeral shaft fracture.

Radiographic views of the shoulder and elbow are necessary to rule out proximal extension of the shaft fracture or

concomitant elbow injury (ie, olecranon fracture). This is especially important in high-energy injuries.

If swelling or evidence of skeletal instability about the forearm is present, dedicated forearm radiographs can determine the presence of a floating elbow (ie, ipsilateral humeral shaft fracture plus both-bone forearm fractures).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distal humerus fracture

Proximal humerus fracture

Elbow dislocation

Shoulder dislocation

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most isolated humeral shaft fractures can be treated non-operatively. Initial treatment can vary with fracture location and involves splinting in either a posterior elbow or coaptation splint. The elbow is positioned in 90 degrees of flexion. An isolated humeral shaft fracture rarely necessitates an overnight hospital stay.

In the past, definitive nonoperative treatment involved coaptation splinting or the use of hanging arm casts. Currently, functional fracture bracing provides adequate bony alignment, whereas local muscle compression and fracture motion promote osteogenesis. These braces provide soft tissue compression and allow functional use of the extremity.11

Timing of brace application depends on the degree of swelling and patient discomfort. On average, the brace is applied about 2 weeks after the injury. A collar and cuff help with initial patient comfort and should be worn during recumbency until the fracture heals.

The brace often requires frequent retightening over the first 2 weeks as swelling subsides. Elbow and wrist range-of-motion exercises out of the sling are encouraged.

Functional bracing requires that the patient be able to sit erect, and weight bearing on the humerus is not allowed. The level of humeral shaft fracture does not preclude the use of functional bracing, even if the fracture line extends above or below the brace.

Anatomic alignment of the humerus rarely is achieved, with varus deformity most common. However, patients often are able to tolerate the bony angulation and still perform activities of daily living after injury. A cosmetic deformity rarely exists.

Pendulum exercises are encouraged as soon as possible postinjury. Active elevation and abduction are avoided until bony healing has occurred to prevent fracture angulation. The surgeon obtains radiographs after brace application and again 1 week later. If alignment is acceptable, repeat radiographs are obtained at 3- to 4- week intervals until fracture healing occurs.10, 11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree