1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Pain related to effort-related sciatica is frequently encountered in different sports. More often than not, the pain results from radicular compression by a lombar discal hernia. Sciatica can nonetheless be explained by other causes such as piriformis syndrome, in which the piriformis muscle compresses the sciatic nerve. Since there exists no consensus as to where the symptoms originate , this syndrome is frequently poorly known, and corresponds to a diagnosis of exclusion . In cyclists, it is favored by traumatic and positional factors along with muscle overwork. More generally, in persons practicing a sport the occurrence of pain due solely to effort and the possibility of pursing the activity explain a frequently lengthy delay in diagnosis . Clinical and supplementary tests remain difficult to interpret. When a radiological abnormality appears (pyramidal muscle hypertrophy, hypersignal of the sciatic nerve), it is not easy to determine whether or not the abnormality accounts for the pains .

In this paper, which reports on two clinical cases involving high-level cyclists, our approach is shown to preclude a variety of diagnoses, the results achieved by supplementary tests are discussed and possible therapeutic strategies are presented .

1.2

Observation

1.2.1

Clinical case 1

A 28-year-old professional cyclist presented with sciatic pain in the left lower extremity triggered by the practice of competitive cycling over 5 years. The intensity of the pain paralleled the intensity of the effort. The pain arose in the rear pelvic area and irradiated through the posterior part of the thigh and the leg. Paresthesias appeared in the same regions without associated lumbar pain. The neurogenic character of the pain was confirmed through the DN4 questionnaire. Trauma in the buttocks area following a fall from a bicycle had been reported 1 year before. The pain was partially attenuated by grade II analgesics. Physical examination revealed leg length inequality, with the right leg 0.5 cm longer than the left. Spinal examination showed lumbar hyperlordosis without pain during mobilization. Straight leg raise (Lasègue test) was painless. Further testing consisting in the piriformis stretching known as the FAIR position (hip joint flexed, adducted and internally rotated) was painful. And while the Freiberg maneuver occasioned no pain, the Pace maneuver elicited pain. No sensomotor deficit or bladder-sphincter dysfunction appeared.

Radiography of the lumbar rachis and the weight-bearing pelvis did not reveal any abnormality. Computer tomography, on the other hand, showed a protruding disc at the L5-S1 right lateral level, but it failed to explain the symptomatology reported on the left side. Moreover, measurement of the isokinetic strength of the lower extremities did not reveal muscle strength deficit. Given the unilateral thigh pains occurring only upon strenuous effort in a high-level cyclist, a vascular hypothesis pointed to external iliac artery endofibrosis was brought forward, only to be eliminated from consideration by a vascular stress test. Finally, an electromyogram with muscles at rest yielded no signs of radicular or truncular lesions.

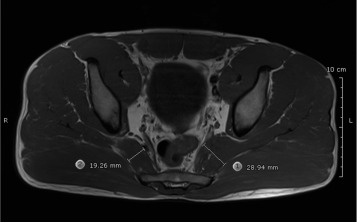

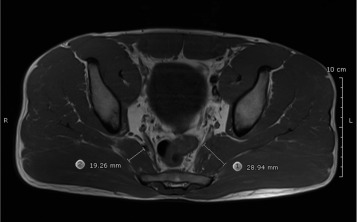

A pelvis MRI scan ( Fig. 1 ) was carried out as part of a search for a local cause of the sciatic trunk pain and showed hypertrophy of the left piriformis muscle (50% larger in size than the contralateral muscle) with compression of the neurovascular bundle, but without any sign of peripheral neuritis.

Another electromyogram, which was performed immediately following effort, objectified a diminished H-reflex of both the right and the left soleus muscles, and the diminution was accentuated on the left side by FAIR positioning.

Initial treatment consisted in administration of analgesics along with physical techniques associating massages, stretching and physiotherapy. As the pain had partially eased, infiltration of local anesthetic and corticosteroids was carried out. On account of insufficient attenuation of the symptoms two months after the initial infiltration, botulinum toxin infiltration took place and led to further partial easing of the pain but did not suffice, given the patient’s practice of a highly demanding sport. And so, it was decided that there would be an operation consisting in release of the pressure on the sciatic nerve and sectioning of the medial two-thirds of the piriformis muscle in contact with the nerve. Intraoperative observations revealed a nerve bundle surrounded by large-scale fibrosis. Since then, training has resumed, but its intensity does not yet allow for informed judgment on the effectiveness of the surgery.

1.2.2

Clinical case 2

The second, 22-year-old cyclist presented with pain solely in the left L5 trajectory after having practiced the sport for 2 years. Paresthesia on the left foot were associated with a prolonged seated position. The pain was exacerbated by maximum physical activity and the effort exerted in the “dancer’s” position. When questioned, the patient also mentioned pelvic trauma from which he had suffered over the previous months.

Clinical examination showed no sign of rachidian abnormality or lumbar disk herniation. Through palpation, a “trigger point” was discovered on the left piriformis muscle. Further testing was focused on the FAIR position and even though no symptoms appeared during the Freiberg maneuver and the Pace and Nagle test, application of the Beatty maneuver provoked pain.

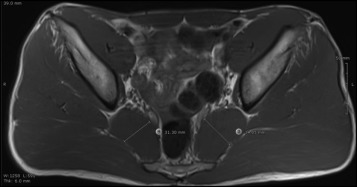

First-time screening and lumbar rachis MRI provided no explanation for the above symptoms. A vascular stress test failed to reveal iliac endofibrosis, and an electromyogram with muscles at rest did not disclose any nerve discomfort. However, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the pelvis ( Fig. 2 ) showed non-significant asymmetry (3 mm) of the left pyramidal muscle associated with hypersignal of the sciatic nerve without lesion to the vascular axes.

In its initial phase, treatment was medical and re-educational. The symptoms eased over a period lasting 18 months. However, a new outbreak of pain subsequently led to anesthetic and corticosteroid infiltration under scannographic control.

In these two clinical cases, a piriformis syndrome diagnosis was given on account of clinical signs and in the absence of any attested lumboradicular cause or radiological abnormality visualized through MRI. In both cases, treatment consisted in physical caretaking associating massages, stretching and physiotherapy. As regards the first athlete, infiltration of local anesthetic and corticosteroids was initially performed but two months later had been shown to be ineffective; it was consequently followed by infiltration of botulinum toxin. Since the athlete deemed insufficient the improvement achieved through medical treatment, surgical treatment ensued.

1.3

Discussion

Piriformis syndrome was reported for the first time in 1947 by Robinson and held responsible for 6% of sciatica cases, but the percentage varied considerably (1 to 15%), according to the studies . The wide range of variation may be explained by the fact that a clear-cut definition of the syndrome eluded researchers. Following elimination from consideration of the other, more frequent causes of sciatica, a diagnosis of exclusion is one remaining option. By definition, piriformis syndrome corresponds to the cases of sciatic or buttocks pain accounted for by a lesion of the sciatic nerve by the piriformis muscle. The damage is “irritative” and/or compressive by dint of different anatomical mechanisms (congenital deformities, hypertrophy of the piriformis muscle, abnormal emergence of the sciatic nerve) or through traumatic mechanisms explaining fibrosis of the piriformis muscle . A number of risk factors have been reported: female sex (risk multiplied by 6), the practice of physical activities such as cycling and long-distance running, leg length inequality, existence of the lumbar hyperlordosis that was diagnosed in clinical case #1 (Section 1.2.1 ).

From a clinical standpoint, a piriformis syndrome diagnosis is based not only on the body of available evidence, but also and more particularly on the absence of a differential diagnosis such as disc pathology, lumbar canal stenosis or pelvic causation. Four symptoms are most frequently found:

- •

buttocks pain;

- •

aggravation of the pain in the seated position;

- •

triggering of the pain during palpation of the greater sciatic notch;

- •

increased pain during the maneuvers provoking tension in the piriformis muscle (Freiberg maneuver, Pace and Nagle test, Beatty maneuver and the FAIR position) ( Table 1 ) .

Table 1

The main clinical tests for the piriformis syndrome.

Name of test

Description

Date of description

Type of maneuver

Pace

With the patient seated the examiner, places his hands on the outside of the knee and resists hip abduction

1976

Active

Beatty

Patient in lateral decubitus position on the healthy side, carries out an abduction against the hip in flexion

1994

Active

Freiberg

Internal rotation and adduction of the tightened limb

1934

Passive

FAIR

Maintaining the hip in flexion, abduction and internal rotation

1981

Passive

It is difficult to assess the sensitivity and the specificity of these maneuvers, which in any event do not suffice to establish a diagnosis. In our two cases, positivity varies according to the tests carried out. In both of them, the FAIR positioning was painful. While all of the maneuvers generate tension in the pelvitrochanterian muscles, they have no specific bearing on the piriformis muscles.

The low specificity of the clinical signs (from 30 to 70% of positivity, according to the different studies, for the Freiberg maneuver and the Pace and Nagle test) and the possibility of carrying on with the physical activities in spite of the pains explain the lapse of time elapsed (2 and 5 years in our two clinical cases) prior to establishment of the diagnosis.

In a cyclist, the piriformis syndrome may be favored by muscle hypertrophy resulting from overwork or positional factors. Pelvic trauma is often found in the medical anamnesis of a cyclist, who practices a sport involving falls. It is difficult to conclusively indicate whether or not the trauma is actually responsible for the piriformis syndrome, which might quite plausibly correspond to an occupational overuse syndrome or cumulative trauma disorder (CTD) occasioned by gestural or other material factors. The local microtraumas caused by repeated contacts with the bicycle saddle could be responsible for compression of the muscle and its vasculonervous bundle. Some of the postures of the cyclist such as the “dancer’s” or so-called “saddle peak” position could contribute to hypertrophy of the piriformis muscle. These types of positional considerations, which are integrally linked to expended effort, may explain why the syndrome cannot be authenticated by paramedical testing of a rider at rest.

From an anatomical standpoint, the association of muscle hypertrophy with anterior compression of the sciatic nerve observed in our patients has been described by Rossi et al. . It serves as an indication for prompt supplementary testing, which eliminate rachidian and pelvic causality from consideration. However, in numerous cases no abnormality is visible by means of radiography, ultrasonography, scanning or electromyography . Only MRI has shown itself effective in study of the piriformis muscle and signs of sciatic nerve compression . That much said, correlation between clinical symptoms and image-based measurements of piriformis muscle size has yet to be clearly established. Russel et al. showed in a study involving 100 subjects that asymmetrical piriformis muscle size frequently occurs without the appearance of any symptom . And so, asymptomatically, 19% of the subjects presented with upper piriformis muscle asymmetry higher than 3 mm, and 8% with asymmetry higher than 5 mm. As for Filler et al., using magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) they reported that piriformis muscle asymmetry was responsible for specificity of 66% and sensitivity of 46% in identification of patients presenting with piriformis syndrome . And when asymmetrical muscle size was associated with a heightened signal at the level of the sciatic nerve, sensitivity and specificity in predicting the results of piriformis muscle surgery rose to 64% and 93% respectively.

The contributions to diagnosis of ultrasonography and tomodensitometry scan are relatively small, and while these types of tests are more widely used during therapeutic procedures, they are less effective in study of the muscle with its signal and the relationships between nerve and muscle.

While electromyogram results are usually normal, in cases of chronic compressions signs of denervation can be observed in the muscles innervated by the sciatic nerve. The absence of paraspinal muscle abnormalities helps to differentiate sciatic compressions from lumbosacral radicular damage. Study of the tibialis posterior or fibular H-reflex has frequently been conducted and can be sensitized by FAIR positioning. In a study on 918 patients presenting with a non-specific clinical syndrome, Fischman et al. analyzed a test demonstrating sciatic nerve damage in the framework of piriformis syndrome. Through comparison with the healthy contralateral leg, which served as a reference, augmented H-reflex sensitivity in the FAIR position was shown . In our first athlete, we found the same characteristics. The interest of these types of electro-physiological tests consists in the fact that they can be easily and simply carried out immediately after effort, which renders them particularly applicable to athletes in whom only physical activity triggers pain.

Treatment of piriformis syndrome is based initially on medical and physical treatments, and subsequently on infiltration techniques necessitating guidance by ultrasound or tomodensitometry . The physical treatment comprises physiotherapy and stretching of the piriformis muscle. As regards the professional cyclist, leg length inequality correction, lumbar delordosis reeducation, suitability of the material used and positional factors on a bicycle have all got to be taken into consideration. Self-stretching techniques can be carried out either seated, standing with a foot on a stool, or according to the “spiral” method .

As for subsequent infiltrations, they involve local anesthetics facilitating a diagnostic test, corticosteroids, or botulinum toxin employed for therapeutic purposes . The use of injected corticosteroids in conjunction with the anesthetics attenuated the pain symptoms at a rate of 71.5%. Some studies tend to show that the botulinum toxin may be more effective than the corticosteroid injections. In 2002, Fischman et al. showed that 12 weeks following the injections, improvement with regard to at least 50% of the pain symptoms had occurred in 65% of the patients treated by botulinum toxin, as opposed to 32% of the patients treated by corticosteroid injection and 6% of the patients having received a placebo .

Forms of piriformis muscle syndrome refractory to these different treatments finally pose the question of a possible indication for surgery, which consists in tenotomy of the piriformis muscle associated with neurolysis of the sciatic nerve . Results after surgery are difficult to interpret; reported series include only a small number of patients, and the methodology has shown a very low level of evidence. Improvement with regard to painful symptoms has ranged from 25 to 100%, without any notion of associated complication.

1.4

Conclusion

Piriformis muscle syndrome corresponds to a diagnosis that should be raised as a possibility in the event of unexplained sciatica signs in an athlete who is able to carry on with his sports activity. The morphological examination yielding positive arguments is MRI. Treatment is based initially and primarily on medical treatment, but once the latter proves ineffective, it may be associated with corticosteroid or botulinum toxin infiltrations subsequent to anesthetic testing. Surgery is exceptional and represents a last resort.

Disclosure of interest

The authors have not supplied their declaration of conflict of interest.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Les douleurs à type de sciatalgie d’effort se rencontrent fréquemment lors de la pratique de certains sports. Le plus souvent la douleur résulte de la compression radiculaire par une hernie discale lombaire. Cependant, les sciatalgies peuvent être expliquée par d’autres causes au premier rang desquels le syndrome du piriforme a été démembré. Cette compression tronculaire par le muscle piriforme représente une cause encore souvent méconnue de douleurs sciatiques en raison de l’absence de consensus pour expliquer l’origine des symptômes . Ainsi, le syndrome du piriforme correspond à un diagnostic d’exclusion . Chez les cyclistes, cette affection est favorisée par des facteurs traumatiques, positionnels et de surmenage musculaire. Chez le sujet sportif, la survenue des douleurs uniquement à l’effort et la possibilité de poursuivre les activités physiques, expliquent un délai diagnostic souvent long . L’interprétation des examens cliniques et complémentaires reste difficile. Lorsqu’une anomalie radiologique (hypertrophie du muscle piriforme, hypersignal du nerf sciatique) est mise en évidence, il n’est, de plus, pas aisé de savoir si celle-ci est responsable des douleurs . À partir de deux cas cliniques, cyclistes de haut niveau, la démarche diagnostique est montrée afin d’éliminer les diagnostiques différentiels, l’apport des examens complémentaires est discuté et les possibilités thérapeutiques sont exposées .

2.2

Observation

2.2.1

Cas clinique 1

Un cycliste de 28 ans, professionnel, présentait des douleurs sciatiques du membre inférieur gauche déclenchées par la pratique du cyclisme en compétition depuis 5 ans. L’intensité de la douleur était parallèle à celle de l’effort. Ces douleurs étaient de topographie fessière et irradiaient à la face postérieure de la cuisse et de la jambe. Des paresthésies étaient présentes dans les mêmes territoires sans douleur lombaire associée. Le caractère neurogène des douleurs était confirmés par l’utilisation du questionnaire DN4. Un traumatisme de la région fessière suite à une chute de bicyclette était rapporté 1 an auparavant. Les douleurs étaient partiellement calmées par la prise d’antalgiques de palier 2. L’examen physique retrouvait une inégalité de longueur de membre inférieur de 0,5 cm aux dépend du côté gauche. L’examen du rachis montrait une hyperlordose lombaire sans douleur à la mobilisation. La manœuvre de Lasègue était indolore. Le testing retrouvait une mise en position FAIR (flexion, adduction, rotation interne de hanche) douloureuse. La manœuvre de Pace déclenchait une douleur, au contraire de celles de Freiberg et Beatty qui étaient indolore. Aucun déficit sensitivo-moteur ni trouble vésico-sphinctérien n’étaient présent.

Les radiographies du rachis lombaire et du bassin en charge ne montraient pas d’anomalie particulière. La tomodensitométrie retrouvait une protrusion discale à l’étage L5-S1 latéralisée à droite ne permettant pas d’expliquer la symptomatologie rapportée du côté gauche. Une mesure de la force isocinétique des membres inférieurs ne montrait pas de déficit de force musculaire. L’hypothèse vasculaire d’une endofibrose iliaque externe était évoquée devant des douleurs de cuisse unilatérales survenant uniquement à l’effort chez un cycliste de haut niveau. Cette hypothèse était écartée par la réalisation d’une épreuve vasculaire à l’effort. L’électromyogramme de repos ne retrouvait pas de signes d’atteinte radiculaire ou tronculaire.

L’IRM du bassin ( Fig. 1 ) était réalisée à la recherche d’une cause locale de souffrance du tronc sciatique et montrait une hypertrophie du muscle piriforme gauche (50 % supérieur à la taille du muscle controlatéral) avec un refoulement du paquet vasculo-nerveux, mais sans signe inflammatoire péri-nerveux.