Physical Examination of the Hand

Accurate diagnosis of hand problems relies on a careful physical examination. The examiner’s skills improve with practice, especially if the examination is organized into a routine that is thorough and efficient. It is wise to follow a specific protocol when examining patients. All clinicians develop their own style when interacting with patients. The best formats are simple, systematic, thorough, and comprehensive.

The physical examination of the hand is organized into eight elements:

Inspection

Palpation

Range of motion assessment

Active motion

Passive motion

Stability assessment

Muscle and tendon assessment

Flexor

Intrinsic

Extrinsic

Extensor

Intrinsic

Extrinsic

Intrinsic

Extrinsic

Nerve assessment

Vascular assessment

Integument assessment

Although it is possible to consider the elements separately, the examiner must understand the interrelationships among these systems to reach accurate conclusions.

Ideally, the patient should be seated, facing directly opposite the examiner. It is helpful to use a narrow table between patient and doctor. This not only allows the patient to comfortably rest the forearm, but also serves as a flat surface that can facilitate some elements of the physical examination.

Inspection

While inspecting the hand, the examiner should look specifically for:

Discoloration

Deformity

Muscular atrophy

Trophic changes (sweat pattern, hair growth)

Swelling

Wounds or scars

Inspecting both of the patient’s hands at the same time is helpful, especially if the problem is unilateral, because the normal hand makes a good reference for comparison.

Discoloration may indicate a wide variety of problems. Skin infections (cellulitis) commonly present with patches of redness with proximal streaking. Vascular inflow problems (arterial blockage) produce white discoloration distally, whereas outflow problems (venous blockage) commonly result in blue or purple, swollen fingers. Hematomas from recent trauma produce patches of purple or blue that eventually change to green and then yellow before they disappear. Some skin cancers produce a dark spot in the skin or a black line in the nailbed. Other skin diseases that have typical appearances are fungal infections, psoriasis, and viral infections.

Inspection for deformity involves looking for asymmetry, unusual angulation, and rotation. Broken bones are often noticeable as a crooked finger. The digital alignment should be checked in full flexion and full extension. The fingers should fold up into the hand when the patient makes a fist, with the fingertips all gently converging toward a common point on the wrist. Malrotated phalangeal or metacarpal fractures are obvious when the patient flexes the fingers, because the affected digit will cross over (or under) an adjacent digit. Comparison with the opposite hand can be helpful. Sometimes after comparing both hands, it becomes clear that what was thought first to be a deformity is simply a minor variation that is “normal” for that particular patient. Inspection for deformity also includes documentation of any missing parts, such as loss of a fingertip or larger part from current or prior injury.

Aside from trauma, other problems that produce deformity include arthritis and inflammatory conditions, such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus, and scleroderma. Tumors may produce deformity from mass effect.

Muscle atrophy also may be noted through careful inspection of the hand. Generalized atrophy may indicate disuse of the extremity, whereas atrophy of certain muscle groups may indicate specific nerve pathology. For example, long-standing carpal tunnel syndrome often results in atrophy of the thenar musculature. Ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow may produce wasting of the interossei muscles, which in severe cases appears as deepened valleys between the metacarpals. Regional atrophy of subcutaneous fat may occur after local steroid injection.

Trophic changes in the hand are important observations to record, because they represent derangement of the sympathetic nervous system. Increased hair growth or altered sweat production (usually increased) may be signs of sympathetically mediated pain and are critical objective markers in making this difficult diagnosis.

Swelling is a common finding of disease or injury and can be identified by careful inspection and comparison with the uninvolved extremity. Localized swelling is a reliable clue to recent trauma or inflammation. Diffuse swelling is also an important finding because it is commonly caused by infection. Generalized swelling also can be indicative of a lymphatic or venous obstruction. Fractures as far proximal as the shoulder routinely result in a swollen hand within the first week after injury because of the effect of gravity on hematomas and traumatic exudates. Snug bandages or casts on the forearm also result in swollen fingers. Note that the dorsal subcutaneous space of the hand can accommodate a fair amount of edema fluid and is often the first area to show swelling, even if the trauma or infection is located on the palmar surface of the hand.

Inspection of the hand should also identify any wounds, skin abnormalities, or preexisting scars. The size and orientation of acute wounds should be carefully noted. The likelihood of nerve, artery, or tendon damage can often be predicted based on the location of the wound. Short, oblique lacerations just distal to the MCP joint of the fourth or fifth finger often result from fistfight injuries. When a clenched fist strikes another person in the mouth, the victim’s tooth can easily cut through the skin of the assailant. This produces a relatively innocent looking laceration that actually represents penetration of the MCP joint capsule and bacterial inoculation of the joint.

Inspection for wounds also should include careful attention to the nail areas and web spaces for puncture sites or skin breakdown that can account for localized infections. Documentation of preexisting scars is important in clarifying any prior injuries or previous surgical treatments that might be relevant to the patient’s current complaints.

The normal flexion creases of the hand and palm are useful reference points when describing the location of wounds or soft-tissue problems. Note that the position of these creases relative to the location of the underlying bone and joint can be misleading. For example, the MCP flexion crease is not situated over the

MCP joint itself, but actually is located over the mid-shaft of the proximal phalanx. The relative location of other skin creases is noted in the following (see “Normal Values”).

MCP joint itself, but actually is located over the mid-shaft of the proximal phalanx. The relative location of other skin creases is noted in the following (see “Normal Values”).

Palpation

Although the rest of the physical examination elements involve palpation, the process of touching the patient’s extremity deserves its own category because it helps focus the remainder of the examination. This initial phase of palpation can be used to identify the following abnormalities:

Masses

Temperature abnormalities

Areas of tenderness

Crepitans

Clicking or snapping

Joint effusion

Although some growths or infections may produce a large enough mass to be seen easily on inspection, palpating the extremity often reveals masses that are not immediately obvious. Enlarged lymph nodes are often more easily felt than seen. Palpation may also demonstrate gross temperature differences between hands, possibly signaling an infectious, inflammatory, or vascular problem. Palpation may be the most useful in situations of trauma, whereby the examination and radiographic evaluation can be focused on those areas of the hand and wrist that are tender. Use of just one fingertip to carefully press on the bony prominences of the wrist and hand can be a remarkably sensitive diagnostic tool. Patients who present with a trigger finger, or tenosynovitis of the digital flexor tendons, often demonstrate tenderness and clicking when palpated over the distal palmar crease for the affected digit.

Range of Motion Assessment

Both passive and active motion should be carefully documented. Passive motion is demonstrated by holding the patient’s finger or wrist and moving the joint in question without having the patient exert any muscular contraction. Active motion is that movement that occurs when the patient’s own muscles contract. Passive motion yields information about joint stiffness owing to bony deformity or soft-tissue contractures. Active motion testing provides information regarding tendon continuity, nerve function, and muscular strength. Every finger joint can be independently tested and in many situations, active and passive motion should be documented for each joint. Aside from the amount of passive and active motion present, it is important to note whether motion causes any pain or is associated with instability or crepitans, as might be the case in situations of acute trauma, infection, or inflammation.

Stability Assessment

Stability testing often requires the examiner to use both hands, usually holding both proximal and distal to the joint in question, and then gently moving the joint passively to stress the ligaments that stabilize the joint. Loss of normal laxity is just as important a finding as too much laxity. Testing should also be done with the finger joints in positions of flexion and extension, because these different positions normally result in differing amounts of joint stability. For example, the true collateral ligaments of the MCP joints are tighter in flexion; therefore, passively flexing the MCP tightens the ligament and allows it to be tested when the joint is stressed side-to-side. A common ligament injury in the thumb is rupture of the ulnar collateral ligament of MCP (gamekeeper’s thumb). Stressing the thumb MCP joint from side-to-side often makes this diagnosis (see “Special Tests”).

The wrist joint is another area in which stability testing is important. The ligament connections between the different carpal bones should be carefully assessed, because instability of the wrist often leads to irregular load distributions and the development of posttraumatic arthritis. Palpation of the carpal bone prominences while the wrist is put through a passive range of motion often demonstrates instability patterns (see “Special Tests”).

Muscle and Tendon Assessment

The muscles and tendons that move the hand and wrist are divided into myotendinous units that have origins and insertions within the hand (intrinsic muscles) and myotendinous units that span the forearm and hand (extrinsic muscles). Both intrinsic muscle and extrinsic muscle groups can be divided into flexors and extensors. Although the ability to make a first and straighten up all the fingers offers general information about active range of motion, more detailed testing of individual muscles and tendons is often necessary. Evaluation of the muscles and tendons should consider both the integrity of the tendon and the strength of the muscle. In general, to test muscle strength you should “ask a muscle to do what it does” and then resist that motion. Muscle strength should be graded using a standard method (Table 1).

Table 1. Grading the strength of muscle contractions | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Specific Testing of Certain Muscles

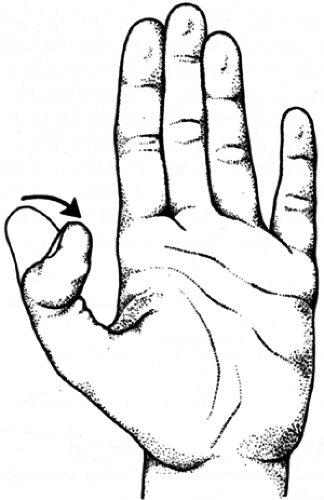

The flexor pollicis longus muscle inserts on the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb and can be tested by asking the patient to flex the distal joint of the thumb (Fig. 1). The flexor digitorum profundus tendon can be tested by asking the patient to flex the distal interphalangeal joint of the involved finger while the examiner blocks flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joint in the same finger and the flexor digitorum profundus function of adjacent fingers (Fig. 2). The flexor digitorum superficialis is tested by asking the patient to flex the proximal interphalangeal joint of only the involved finger. The other fingers must be blocked in extension to avoid interference from the flexor digitorum profundus of the finger being examined (Fig. 3). The flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor carpi radialis are tested by asking the patient to volar flex the wrist and then palpating the tendon or muscular contraction in its anatomic location.

The first dorsal wrist compartment contains the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus (APL), which inserts at the dorsal base of the thumb metacarpal, and the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB), which inserts at the dorsal base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb. These are evaluated by asking the patient to “bring

your thumb out to the side” (Fig. 4). The examiner can palpate the taut tendons over the radial side of the wrist going to the thumb.

your thumb out to the side” (Fig. 4). The examiner can palpate the taut tendons over the radial side of the wrist going to the thumb.

The second dorsal wrist compartment contains the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) muscles (Fig. 5). They insert at the dorsal base of the index and middle metacarpals, respectively. These are evaluated by asking the patient to “make a

fist and bring your wrist back strongly.” The examiner can give resistance and palpate the tendons over the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist.

fist and bring your wrist back strongly.” The examiner can give resistance and palpate the tendons over the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree