Abstract

Introduction

Physical and rehabilitation medicine physicians commonly see patients with chronic functional ankle instability. The main anatomical structures involved in ankle stability are the peroneus (fibularis) brevis and peroneus longus muscles. Several anatomical muscle-tendon variations have been described in the literature as being sometimes responsible for this instability, the peroneus quartus muscle being the most frequent. The objective of this clinical study is to discuss the implication of the bilateral peroneus quartus muscle in functional ankle instability.

Clinical case

This 26-year-old patient was seen in PM&R consultation for recurrent episodes of lateral ankle sprains. The clinical examination found a moderate hyperlaxity on the right side in bilateral ankle varus. We also noted a bilateral weakness of the peroneus muscles. Additional imaging examinations showed a supernumerary bilateral peroneus quartus. The electroneuromyogram of the peroneus muscles was normal.

Discussion

In the literature the incidence of a supernumerary peroneus quartus muscle varies from 0 to 21.7%. Most times this muscle is asymptomatic and is only fortuitously discovered. However some cases of chronic ankle pain or instability have been reported in the literature. It seems relevant to discuss, around the clinical case of this patient, the impact of this muscle on ankle instability especially when faced with lingering weakness of the peroneus brevis and longus muscles in spite of eccentric strength training and in the absence of any neurological impairment. One of the hypotheses, previously described in the literature, would be the overcrowding effect resulting in a true conflict by reducing the available space for the peroneal muscles in the peroneal sheath.

Résumé

Introduction

L’instabilité chronique de cheville est un motif fréquent de consultation en médecine physique et de réadaptation. Parmi les structures anatomiques impliquées dans la stabilité de la cheville, les muscles fibulaires tiennent une place de choix. De nombreuses variations anatomiques de leurs tendons ont été décrites, parfois responsables d’instabilité. Le peroneus quartus est l’une des plus fréquentes. L’objectif de ce cas clinique est de discuter l’imputabilité de la présence d’un quatrième fibulaire bilatéral, chez un patient souffrant d’instabilité chronique.

Observation

Il s’agit d’un patient de 26 ans venant consulter pour des épisodes d’entorses latérales à répétition. L’examen clinique retrouve une hyperlaxité en varus bilatérale, modérée, prédominant à droite et un déficit bilatéral de force musculaire des fibulaires. Le bilan d’imagerie a mis en évidence la présence d’un muscle peroneus quartus bilatéral. L’électroneuromyogramme des muscles fibulaires est normal.

Discussion

L’incidence du peroneus quartus varie selon les séries de 0 à 21,7 %. Le plus souvent, ce muscle surnuméraire est asymptomatique et de découverte fortuite. Cependant quelques cas de douleurs chroniques de cheville ou d’instabilité ont été rapportés dans la littérature. Il nous semble intéressant de discuter chez ce patient la responsabilité de ce muscle dans l’instabilité devant la persistance d’un déficit de force des muscles fibulaires malgré un travail de renforcement adapté, en l’absence de lésion neurologique. L’une des hypothèses que nous évoquons est celle précédemment décrite d’inadéquation de volume contenu/contenant au sein de la gaine des fibulaires.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Functional ankle instability (FAI) is a common reason for consulting a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician specialized in sports trauma. FAI is the most common complication of ankle sprains with an incidence that can go up to 40% according to the series. FAI is a subjective functional symptom to be differentiated from laxity, which is an objective clinical symptom. Thus an instable ankle is not necessarily due to hyperlax ligaments and conversely hyperlaxity of the ankle ligaments is not systematically responsible for FAI. However, the presence of hyperlaxity increases the risk of instability .

Today, thanks to the work of Freeman , we are able to differentiate two types of instability: “mechanical” instability due to lesions on the ligaments responsible for objective clinical laxity and “functional” instability correlated to proprioceptive and neuromuscular command impairments. However several other pathologies can be the cause or consequence of this chronic ankle instability: osteochondral lesions, especially of the talus (OLT), lesions of the peroneal tendons, some postural disorders of the ankle of feet or some neurological impairments (common fibular – or common peroneal – nerve). Among the bones, ligaments, tendons or muscles involved in ankle stability, muscles and tendons of the peroneus brevis and longus muscles are especially important . They act as active stabilizers of the talocrural joint, but also of the subtalar and midfoot joints. Several anatomical tendon abnormalities were described in the literature as being responsible for clinical symptoms such as instability . The presence of a supernumerary peroneus quartus (PQ) muscle was reported as one of the most common. The incidence of this muscle varies according to the series from 0 to 21.7%. This PQ muscle commonly arises from the peroneus brevis muscle and inserts into different areas such as the retrotrochlear eminence of the calcaneum, peroneus longus tendon, tuberosity of the cuboid, to only list the most common insertions. Most times, this supernumerary muscle is discovered fortuitously and is not responsible for any symptoms. However a few cases of chronic ankle pain, peroneal tendon sprains or ankle instability were reported in the literature . The objective of this clinical case is to discuss the impact of this supernumerary PQ muscle on functional ankle stability.

1.2

Patient and method

We report the case of a 26-year-old patient who consulted for recurrent episodes of lateral ankle sprains. These episodes started at the age of 17 following minor trauma or even no trauma at all. Besides these acute episodes, the patient reported a sensation of bilateral instability, with no predominant side, when walking on uneven ground and jogging. He stopped all athletic activities and sports the year before. He also described some bilateral retromalleolar pain triggered during instability incidents. After each sprain he benefited from specific therapeutic care, he wore a specific ankle orthotic and attended a well-conducted rehabilitation training program (e.g. strengthening of the peroneus muscles, proprioceptive work), yet no symptom improvements were noted. Furthermore this patient did not have any personal or family history and was not under any treatment. After this first consultation we suggested a thorough check-up to refine the etiological diagnosis of this FAI.

1.3

Results

At the clinical examination we found a genu varum (varus knee) and bilateral pes valgus planus. Joint amplitudes of the foot and ankle were normal. The tests highlighted a bilateral muscle strength deficit for the peroneus brevis and longus evaluated at 4-/5. There was no deficit of the tibialis posterior muscle. No signs of tendon dislocation for the peroneus brevis muscles or tibialis posterior muscle. A check-up of the ligaments unveiled a hyperlaxity in bilateral varus predominant on the right side. There was no positive sign at the anterior drawer test. Furthermore, we did not see any evidence of constitutional hyperlaxity at the examination. These tests did not highlight any sensitive disorders. The rest of the neurological examination was eventless. Finally, pain was elicited at the palpation of the tarsal sinus and lateral peroneal groove behind the malleolus on the right and left sides. On a functional level, we conducted a gait analysis, the patient was first barefoot then he was asked to wear his shoes. During the swing phase we reported a positioning of the feet in varus. The initial step contact was made by the foot’s lateral border. We then observed, during the stance phase, a passage in bilateral valgus. The quantitative gait parameters measured with the GAITRite ® system were normal. We used force platforms for balance analysis. The balance in double support stance was normal (surface covered by the center of gravity at 0.72 cm 2 , length at 31 cm). However, we noted a bilateral alteration of balance in single support stance, predominant on the right side (surface covered by the center of gravity at 15.3 cm 2 on the left side and 36.4 cm 2 on the right side; length at 182 cm on the left side and 184 cm on the right side). Furthermore, single support stance could not be kept for 30 seconds without help. Standard radiographic imaging did not unveil any abnormality. Dynamic X-rays did not show any anterior drawer laxity. However, we found a bilateral hyperlaxity in forced varus at 15° on the left side and 20.5° on the right side for a positive threshold set at 10° ( Fig. 1 ).

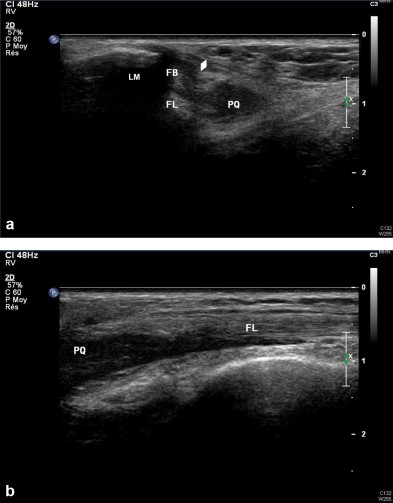

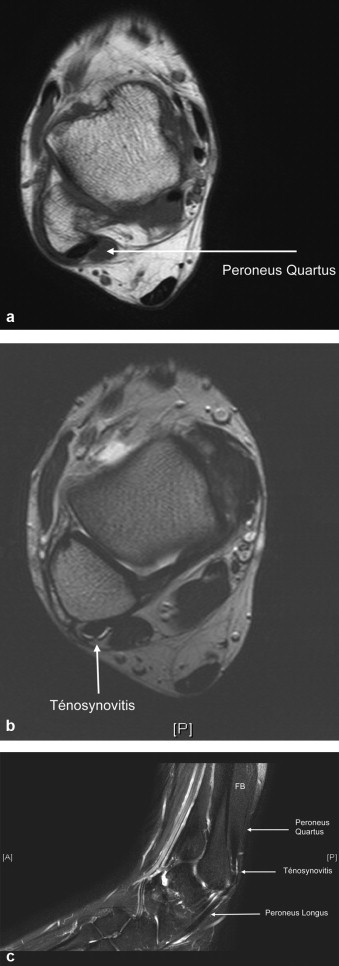

An ultrasound of the ankles ( Fig. 2 ) showed the presence of a supernumerary bilateral muscle: the PQ muscle, stemming from the peroneus brevis and inserted distally on the tendon of the peroneus longus muscles at the level of the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus. It was associated to a thickening of the superior peroneal retinaculum. As for the ligaments, some scarring was noted on the left anterior talofibular ligament. On the right side, the latter is moderately thickened without discontinuity. This examination was completed by a bilateral MRI ( Fig. 3 ) validating these elements but also showing a tenosynovitis of the peroneus brevis and longus muscles.

An electromyogram was also prescribed to look for a neurological etiology for the strength deficit of the peroneal muscles but it was normal. Finally, a concentric isokinetic testing of the evertor and invertor muscles (three repetitions at 30°/s) was performed. Compared to a group of 53 healthy volunteers described by Willems et al. , we noted a strength deficit for the evertor muscles in concentric mode at 30°/s on the right side only and in eccentric mode, at 30°/s also, on both sides. The values of peak torque to body weight ratio were for the evertor muscles (in concentric mode at 30°/s) 39.3% on the left side and 28.6% on the right side for normal values set between 40 and 42%. In eccentric mode these values were 29.8% on the left side and 21.4% on the right side for normal values set between 43 and 45%.

At the end of this thorough check up, our patient did 15 new rehabilitation sessions focused on strength training of the peroneal muscles mainly in eccentric mode associated to proprioceptive work (protocol identical to the recommendations published by the HAS in January 2000 [French National Health Agency] ). He was also prescribed some custom-made orthopedic shoes, to compensate his bilateral pes valgus planus disorder. A surgical consultation was scheduled to look at a possible resection of this supernumerary muscle. In fact, faced with the persistent instability symptoms and the strength deficit of the peroneal muscles still seen during clinical testing, we wanted to evaluate the responsibility of this PQ muscle in this lingering strength deficit and thus chronic bilateral FAI symptoms of this patient.

1.4

Discussion

FAI, common complication of lateral ankle sprain, has several etiologies going from lesion of the ligaments to a deficit in muscle strength not forgetting tendon, osteochondral or neurological lesions. In this patient, it seems that the bilateral ankle instability is caused by several factors. In fact, he present a pes valgus at the back of the foot with collapsing of both medial arches, deficit of peroneal muscle strength and ligament hyperlaxity predominantly on the right side. He also has bilateral pes valgus postural disorders. Thus, when walking or worse when running, during the initial stance phase the back of his foot is responsible for impact between the tip of the lateral malleolus and the orifice of the tarsal sinus. This bone contact triggers some pain. Furthermore, in patients with this type of postural disorders, some muscle strength imbalance was described between the tibialis posterior and the peroneus brevis . In fact, when standing up, the valgus deformity relaxes the peroneus brevis muscle thus weakening its action. In order to take all these data into account, our patient had custom orthopedic shoes made, with inbuilt arch support and cupped heal, however no significant symptoms improvement was noted. Furthermore, there probably is an associated deficiency of the ligaments since at the clinical examination we found a hyperlaxity in bilateral varus validated by dynamic X-rays. This patient also showed some bilateral strength deficit of the peroneal muscles, seen at the clinical examination and validated during isokinetic testing. Some authors have reported that a deficit of evertor muscles strength was one of the major risk factors for FAI . However no neurological impairment was detected during the electroneuromyogram. The rehabilitation training program specifically designed for our patient (e.g. eccentric peroneal muscle strengthening, proprioceptive work) did not improve the symptoms. Our check-up also unveiled a supernumerary bilateral PQ muscle; its responsibility in our patient’s FAI should be discussed. The PQ is a supernumerary muscle of the distal lateral portion of the fibula. It was first described by Otto in 1816 then studied in depth by Ledouble in an anatomical report in 1897. Afterwards, various anatomical or imaging studies as well as a few clinical cases were published indicating that this muscle was responsible for various symptoms (e.g. pain, swelling, instability). Its incidence varied according to the various studies: after dissection, Sobel et al. found a PQ on 27 of the 124 legs studied (21.7%), versus six PQ muscle for 46 legs (13%) for Hecker and finally zero PQ muscle out of 88 legs (0%) for Shane Tubbs . Cheung et al. analyzed 136 ankle MRI exams and reported a PQ muscle in 14 of them (10%) versus 11 out of 65 (17%) for Saupe et al. and seven out of 32 (22%) for Chepuri et al. . Finally, in an anatomical and imaging study (dissection of 102 legs and review of 80 ankle MRI exams) Zammit and Singh reported an overall incidence of 6.6% (12/182). Furthermore, most authors reported a male predominance (2.5/1 for Saupe et al. ). The PQ muscle usually stems from the peroneus brevis at about 1/3 of the leg; however some cases of emergence from the peroneus longus were also reported (15% of cases for Sobel et al. ). However, it can insert itself into several sites. Authors have been arguing about the most common insertion site: for Zammit et al. it is the retrotrochlear eminence of the calcaneum (50% of the dissections and 83% of MRI exams) just like for Cheung et al. (78%) but for Sobel et al. it was the peroneal tubercle of the calcaneus (63%). In most cases, there was some reported hypertrophy of the insertion sites. Other less common insertions were described such as the tendon of the peroneus brevis or longus, the cuboid, the base of the fifth metatarsal or the superior peroneal retinaculum. This muscle was named differently according to the insertion sites; however authors seemed to agree that all these different forms were only variations of the PQ muscle. As a reminder, our patient has a bilateral PQ muscle stemming from the muscle tissue of the peroneus brevis with a distal insertion on the tendon of the peroneus longus muscle. Most times, this supernumerary muscle is completely asymptomatic and is fortuitously discovered during imaging exams. However several cases of chronic pain and swelling of the ankle have been described. More rarely cases of an association with FAI were reported. Finally, some examples of chronic dislocation of the peroneal tendons were mentioned .

These symptoms can spontaneously appear but usually they are triggered by acute trauma such as lateral ankle sprain. Trono et al. then Oznur et al. reported the progressive onset of pain and swelling behind or under the lateral malleolus in women over the age of 50. The symptoms disappeared after surgical resection of the PQ muscle followed by short immobilization time and rehabilitation training. Sammarco and Brainard described the case of a 22-year-old woman, high-jump athlete, with ankle and feet pain that appeared spontaneously. This pain led the patient to decrease her athletic training and she even ended up stopping all her athletic activities. The surgical exploration identified and resected the supernumerary PQ and a few weeks afterwards the pain stopped. Different cases of patients with chronic pain and swelling around the ankle after “lateral ankle sprain” were studied by Moroney and Borton , White et al. and Kim and Berkowitz . After all conservative treatments failed, the surgical explorations validated the presence of supernumerary PQ muscles and after surgical resections all symptoms disappeared. For Martinelli and Bernobi , a simple fasciotomy proved to be effective.

Finally, Donley and Leyes reported the case of a 15-year-old football player complaining about painful popping of the peroneal tendons after severe lateral ankle sprains. Surgical resection was also effective in that case. There are very few publications regarding the association of supernumerary PQ muscle and FAI. Coudert and Kouvalchouk presented two cases of female patients with painful FAI, at first evoking a recurrent dislocation of the peroneal tendons. During surgical exploration, a supernumerary muscle fascia that could have been a remnant of a PQ was found, without any obvious abnormality of the peroneal groove, retinaculum or tendons. The surgical resection was effective; the patients could get back to sports activities without any pain or FAI. In the same manner, Hammerschlag and Goldner described some instability consecutive to the presence of a peroneus digiti minimi muscle and Regan and Hughston reported a clinical picture of FAI with the discovery during surgery of a trifurcation of the peroneus brevis, probably a remnant of a supernumerary muscle. The surgical excision of the two accessory tendons made the instability disappeared. Several hypotheses were emitted by these different authors to try and explain the onset of such symptoms. For Coudert et al. , a PQ within the peroneal sheath brings a real conflict between a “normal” sheath and its unusual voluminous content due to PQ preventing tendons from gliding properly. The increase in muscle volume during efforts would appear to be the triggering element for these symptoms (pain, instability). This was also properly described in the Anglo-Saxon literature. Sobel et al. , in their anatomical study, reported the presence of tendon lesions of the peroneus brevis muscle in 18% of the patients with PQ. They named this the “retromalleolar attrition syndrome”. White et al. described an “overcrowding effect” as the pathophysiological mechanism behind these lesions. Finally, the term “lateral ankle stenosis syndrome” was first used by Donley and Leyes then again by Moroney and Borton , they described a prominent body of the PQ within the peroneal sheath reducing the available space for proper functioning of the peroneal tendons or even compressing them.

In our patient, these phenomena could be worsened by the pes valgus planus disorder, reducing also the lateral retromalleolar space. In regards to these different publications and our patient’s symptoms, it seems difficult to render PQ the sole responsible for bilateral FAI (inadequate ratio between its relatively high incidence: up to 21.7% according to the series, and the very few symptomatic cases reported), however it seems that it partially contributes to this instability. In fact, we observed in our patient, a lingering strength deficit on the peroneal muscles (clinical testing and isokinetic evaluation), in spite of a well-conducted rehabilitation training program. Furthermore, the imaging examinations, especially dynamic ultrasound, validated the presence of the PQ within the sheath, not as a tendon, but rather as a plump muscle tissue reducing the available space for the peroneal tendons. This elicited some lesions on the retinaculum that appeared to be thicker than normal. This concurs with the results described by Coudert, of a real conflict within the peroneal sheath due to the inadequate relationship between content/container volumes. The fact that symptoms appear during an effort could be explained by the phenomenon of muscle swelling worsening the conflict and thus leading to a real lateral ankle stenosis syndrome by overcrowding effect.

Furthermore by trying to strengthen the peroneus brevis and longus, we also probably strengthen the PQ thus increasing the conflict within the sheath by increasing the volume of this supernumerary muscle. Finally, the presence of this PQ muscle can explain the lateral retromalleolar pain in our patient. Regarding the various therapeutic options, the authors seem to agree on the fact that in case of failure of the various medical therapeutic options (e.g. rehabilitation, rest, and injections), surgical resection of this supernumerary muscle with retinaculum restoration and postoperative care including a short immobilization followed by a specific rehabilitation protocol can totally eliminate the symptoms. Patients can get back to sports or athletic activities after a few months.

1.5

Conclusion

The PQ is the most common supernumerary muscle of the distal lateral portion of the fibula (up to 21.7% according to the series). However its symptomatic clinical presentation seems quite rare and harder to demonstrate. We report here the clinical case of a young patient presenting a debilitating bilateral FAI (stopped all athletic activities) in spite of a well-conducted medical treatment. If it seems obvious that the symptoms presented are probably due to several factors (postural dynamic disorders due to pes valgus planus, hyperlaxity due to ligament insufficiency, peroneal muscle strength deficit), it seems that the presence of a bilateral PQ muscle is involved in this FAI. It seems also relevant to establish a diagnosis as early as possible to avoid lesions of the ligaments resulting from recurrent ankle sprains that will then foster this chronic instability. Faced with pain or chronic instability after trauma, or lingering instability or strength deficit of the peroneal muscles in spite of well-conducted rehabilitation sessions, the possibility of a supernumerary PQ should be looked at. Its presence will be quickly validated by imaging exams (ultrasound or MRI). Finally the adapted therapeutic solution seems to be surgical resection, leading to good results with complete disappearance of the symptoms for all reported cases. In our patient, given the associated ligament insufficiency, an associated arthroscopic surgical reconstruction of the injured ligaments could be proposed and eventually take place at the same time as the resection.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’instabilité chronique de cheville est un motif fréquent de consultation en médecine physique et de réadaptation et plus particulièrement en traumatologie du sport. Il s’agit de la complication évolutive la plus fréquente des entorses de cheville dont l’incidence est estimée jusqu’à 40 % selon les séries. C’est un symptôme fonctionnel subjectif à différencier de la laxité qui est un signe d’examen clinique objectif. Ainsi une cheville instable n’est pas forcément hyperlaxe et inversement, une hyperlaxité de cheville n’est pas systématiquement responsable d’instabilité. Cependant, la présence d’une hyperlaxité majore le risque d’instabilité .

Classiquement, suite aux travaux de Freeman , on distingue deux grands types d’instabilité : l’instabilité « mécanique » imputable à des lésions ligamentaires responsable d’une laxité clinique objective et l’instabilité dite « fonctionnelle » corrélée à un déficit proprioceptif et de commande neuromusculaire. Cependant, d’autres pathologies variées peuvent être cause ou conséquence de l’instabilité chronique de cheville : les lésions ostéochondrales (notamment du dôme du talus), les lésions des tendons des fibulaires, certains troubles statodynamiques de la cheville et du pied ou encore certaines atteintes neurologiques (nerf fibulaire commun).

Parmi les éléments osseux, ligamentaires ou tendinomusculaires impliqués dans la stabilité de la cheville, les muscles et tendons des long et court fibulaires tiennent une place de choix . Ce sont des stabilisateurs actifs de l’articulation talo-crurale, mais également des articulations sous-talienne et du médio-pied.

De nombreuses variations anatomiques de ces tendons ont été décrites responsables dans certains cas d’une symptomatologie clinique et notamment d’instabilité . La présence d’un muscle surnuméraire, le peroneus quartus, est l’une des plus fréquentes. L’incidence de ce muscle varie selon les séries de 0 à 21,7 %. Son origine est le plus souvent commune avec celle du muscle court fibulaire et sa terminaison très variable : éminence rétrotrochléaire du calcanéum, tendon du long fibulaire, tubérosité du cuboïde pour ne citer que les plus fréquentes.

Le plus souvent, ce muscle surnuméraire est de découverte fortuite et n’est responsable d’aucune symptomatologie. Cependant quelques cas de douleurs chroniques de cheville, de luxation des tendons des fibulaires ou d’instabilité ont été rapportés dans la littérature .

L’objectif de ce cas clinique est de discuter l’imputabilité de la présence d’un peroneus quartus bilatéral sur l’instabilité chronique de cheville.

2.2

Patient et méthode

Il s’agit d’un patient de 26 ans venant consulter pour des épisodes d’entorses latérales à répétition des chevilles. Celles-ci ont débuté à l’âge de 17 ans et ont toujours fait suite à des traumatismes mineurs voire en l’absence de traumatisme. En dehors de ces épisodes aigus, il rapporte une sensation d’instabilité bilatérale, sans côté dominant, survenant à la marche en terrain accidenté et à la course, l’ayant contraint à stopper toute activité sportive depuis un an. Il décrit également des douleurs bilatérales, prémalléolaire inférieure déclenchées survenant lors d’accidents d’instabilité. À la suite de chacune de ses entorses, il a bénéficié d’une prise en charge spécifique avec port d’une orthèse et rééducation bien menée (renforcement des muscles fibulaires, travail proprioceptif…), sans amélioration de la symptomatologie.

Ce patient ne présente par ailleurs aucun autre antécédent personnel ou familial notable et ne prend aucun traitement.

Au terme de cette première consultation, nous lui avons proposé de réaliser un bilan plus complet afin de préciser le diagnostic étiologique de cette instabilité chronique.

2.3

Résultats

À l’examen clinique, on retrouve un morphotype en genu varum et un pied plat valgus bilatéral. Les amplitudes articulaires de la cheville et du pied sont normales et symétriques. Sur le plan musculaire, le testing met en évidence un déficit de force des muscles long et court fibulaire évalué à 4-/5 et ce de façon bilatérale. Il n’y a pas de déficit du tibial postérieur. Il n’y a pas de signe clinique de luxation tendineuse des fibulaires ou du tibial postérieur. Le bilan ligamentaire fait état d’une hyperlaxité en varus bilatérale prédominant à droite. Il n’y a pas de tiroir antérieur. On ne note, par ailleurs, pas de signe d’hyperlaxité constitutionnelle à l’examen. Notre examen ne permet pas de mettre en évidence de trouble sensitif. Le reste de l’examen neurologique est sans anomalies. Enfin, une douleur est déclenchée à la palpation du sinus du tarse et des gouttières rétromalléolaires latérales, à droite comme à gauche.

Sur le plan fonctionnel, l’examen analytique de la marche pieds nus puis chaussés objective, lors de la phase oscillante, un positionnement des pieds en varus. L’attaque du pas se fait ainsi par le bord latéral du pied. On observe ensuite lors de la phase d’appui un passage en valgus bilatéral.

Les paramètres quantitatifs de marche mesurés sur le GAITRite ® sont normaux.

Une évaluation de l’équilibre est réalisée sur plateformes de force. L’équilibre en station debout bipodale est normal (surface parcourue par le centre de gravité à 0,72 cm 2 , longueur à 31 cm). En revanche, on note une altération bilatérale de l’équilibre en station monopodale prédominant à droite (surface parcourue par le centre de gravité à 15,3 cm 2 à gauche et 36,4 cm 2 à droite ; longueur à 182 cm à gauche et 184 cm à droite). De plus, l’appui monopodal ne peut être tenu 30 secondes sans aide.

Le bilan radiographique standard est sans anomalies. Les clichés dynamiques ne mettent pas en évidence de laxité en tiroir antérieur. Il existe en revanche une hyperlaxité bilatérale en varus forcé de 15° à gauche et 20,5° à droite pour un seuil de positivité supérieur à 10° ( Fig. 1 ).