Percutaneous Fixation of Proximal Humeral Fractures

Raymond R. White

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

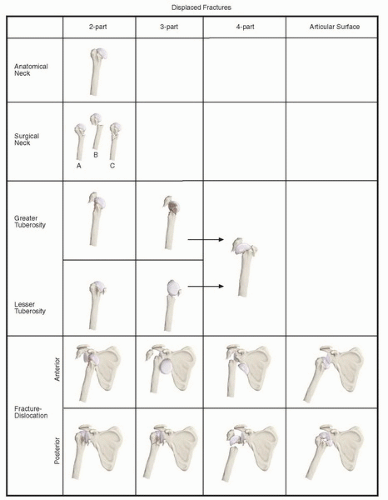

Percutaneous fixation of proximal humeral fractures is an excellent example of indirect reduction and minimal stable fixation. This procedure allows rapid healing and return to a normal function. The Neer classification accounts for displacement and angulation and is used to classify proximal humerus fractures (Fig. 34-1). Percutaneous fixation is most commonly used to treat two-part fractures or those involving the surgical neck and the isolated greater tuberosity fracture. However, this technique is also optimal for three-part fractures because it preserves the tenuous blood supply to the head fragment. This technique, therefore, should be considered for physiologically young patients who wish to save their own humeral head and avoid prosthetic replacement. Occasionally, percutaneous fixation can be used on four-part fractures. The risk of avascular necrosis associated with this procedure precludes its use in circumstances other than for young patients who want to save the humeral head.

Contraindications for percutaneous fixation are head-splitting fractures; four-part fractures in the elderly; uncooperative patients; pathologic bone; and metaphyseal extension. This technique is not a substitute for prosthetic replacement in the elderly with four-part fractures or fractures in which the humeral head is split and not able to be reconstructed. Patients must be cooperative and not confused. Postoperative patient confusion may lead to loss of fixation and poor results. If adequate fixation is not possible because of osteopenia or pathologic (tumor) bone, another technique should be used. This technique cannot be used in fractures with metaphyseal comminution. These fractures, in which length is an important issue, should be stabilized with plate fixation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Initially, the patient’s limb is evaluated for neurovascular compromise, especially the axillary nerve. Considerable shoulder swelling is not unusual, and ecchymosis often extends into the forearm and chest wall.

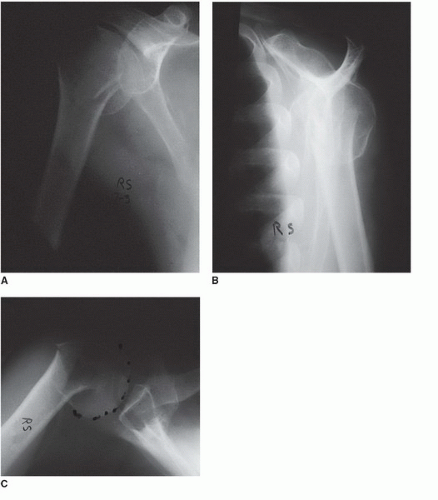

Radiographic views include an anteroposterior (AP), scapular Y, and axillary lateral views of the shoulder (Fig. 34-2). A true AP view of the humerus (with the arm in a neutral position) may be useful to determine head impaction. The axillary view is helpful in determining AP angulation and lesser tuberosity displacement. A computed tomography scan is rarely necessary, and magnetic resonance imaging is not helpful in determining head vascularity in the acute phase.

Timing of the surgery is critical only if the head is dislocated. A dislocated humeral head must be relocated as an emergency. Occasionally, it is possible to reduce the head dislocation by closed methods, but an open approach is usually required. If the head is not dislocated, surgery can be done on an elective basis, usually 3 to 7 days after injury. If there are no associated medical problems, surgery can be done in an outpatient setting. The patient is placed in a sling-and-swathe shoulder immobilizer until surgery. Pre- and postoperative pain management are the same: The patients are given scheduled acetaminophen (1,000 mg every 6 hours) and ibuprofen (400 mg every 6 hours), with oxycodone (5 to 10 mg every 2 hours) for breakthrough pain.

SURGERY

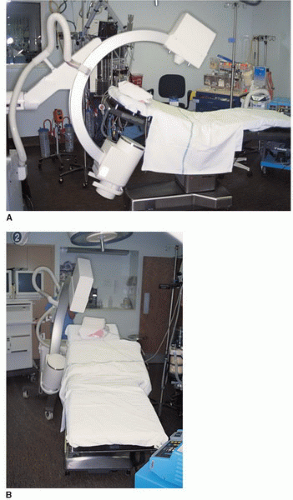

After the patient is anesthetized, the table is turned 90 degrees, with the anesthesia staff and their equipment on the unaffected side, allowing sufficient room for the surgeon on the affected side. The image intensifier is positioned at the head of the table with the video monitors near the base unit on the affected side (Fig. 34-3A). The C-arm is positioned so the machine can swing 90 degrees to obtain an axillary view. The “C” should be positioned to swing either under or over, depending on the position of the patient. It is helpful to tilt the upper portion of the “C” medially and the lower portion of the “C” laterally to keep the table from interfering with the image (Fig. 34-3B).

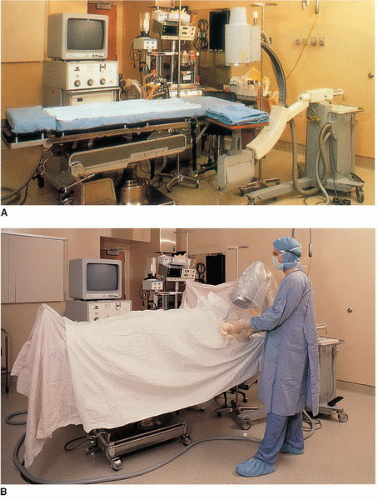

Patients can be positioned in one of two ways. The first is to place the patient flat on a level operating room table with the head at the foot of the table (backward on the table), so the table cranks are not in the way of the x-ray machine (Fig. 34-4A). The patient is then moved laterally on a radiolucent board so the shoulder is over the edge of the table. The advantage of this position is threefold: Two-part fractures tend to stay reduced; the image intensifier sending unit is below the table and farther from the surgeon; and the image swings under the drapes, facilitating an axillary view (Fig. 34-4B).

In the second position, the patient is placed in a beach-chair position (Fig. 34-5A) with the shoulder over the edge of the table. The image intensifier is turned so the sending unit is up and can be swung over the top for the axillary view. This position provides an easy table setup, and if open reduction is necessary, the position is a familiar one. Unfortunately, the C-arm must be swung over the top to obtain an axillary view, and the x-ray unit is closer to the surgeon’s head, increasing exposure to the surgeon (see Fig. 34-5B).

FIGURE 34-4 A: The patient is positioned flat on the operating room table. The patient’s head is at the foot of the table. This keeps the table cranks from interfering with the image intensifier. B: The axillary view is easy to obtain in this position by swinging the image under the shoulder. (From White, R.R.: Proximal humeral fractures: percutaneous fixation. In: Wiss, D.A., ed.: Master techniques in orthopaedic surgery: fractures. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998: 19-33.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|