Pelvic Fractures: Sacral Fixation

Mark C. Reilly

Brent L. Norris

Michael J. Bosse

James F. Kellam

Stephen H. Sims

Indications/Contraindications

Although sacral fractures may occur as an isolated injury, most commonly they occur as one component of a pelvic ring injury. Notoriously difficult to diagnose on plain films, a sacral injury is often found by a surgeon who displays a high index of suspicion based on the mechanism of injury and physical examination. Even nondisplaced or minimally displaced sacral fractures may be unstable and have the potential to displace prior to healing. Therefore, the orthopedic surgeon is challenged to identify and treat sacral fractures knowing that these injuries are at high risk for displacement. Information such as the pattern of the sacral fracture, its location, disruption of surrounding bone and soft-tissue structures, mechanism of injury, and the severity of the anterior pelvic-ring injury must be considered by the surgeon determining the inherent stability of a sacral fracture.

Denis et al classified sacral fractures according to their relationship to the sacral foramina. This classification system correlates with neurologic injury as well. Zone I injuries are lateral to the sacral foramina and are associated with L5 nerve-root injuries in 20% to 25% of cases. Fractures through the sacral foramina are zone II injuries, and injury to the sacral nerve roots occur in up to 50% of patients with this type of fracture. If the fracture is medial to the sacral foramina, the injury is in zone III, and neurologic injury with bowel and/or bladder dysfunction occurs in up to 70% of zone III patients.

Stable sacral fractures can be managed symptomatically with a short period of bed rest followed by mobilization and protected weight bearing until healed. Prolonged bed rest or traction is not recommended in unstable injuries because of the inherent risks of deep venous thrombosis, pressure ulceration, and aspiration or pneumonia. Frequent radiographic follow-up is mandatory to identify fractures that, although initially thought to be stable, subsequently displace following mobilization. Sacral fractures medial to the L5–S1 facet joint are more constrained by the disc and facet joint capsule and are less prone to displacement than alar or transforaminal fractures. Fractures caused by a lateral

compression mechanism are also less likely to displace than anterior-posterior compression and “vertical shear” injuries.

compression mechanism are also less likely to displace than anterior-posterior compression and “vertical shear” injuries.

Displaced and unstable sacral fractures require reduction and fixation. Because instability is often difficult to ascertain, displacement is more often cited as the indication for surgical treatment. Displacement of greater than 1 cm in the posterior pelvic ring is generally accepted as an indication for reduction and fixation. Complex pelvic-ring injuries that include a sacral fracture may also benefit by fixation such that patient mobilization is improved. Reduction and fixation of displaced sacral fractures that are associated with neurologic injury may help improve the chance for neurologic recovery. As with any injury, associated traumas, medical comorbidities, patient age, and preinjury functional level must be considered in determining appropriate treatment.

Preoperative Planning

In patients with pelvic fractures, full trauma evaluation and resuscitation with basic and advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols are essential. The evaluation of patients with a pelvic ring injury includes a visual examination and palpation of the back, buttocks, flank, groin, and perineum so the integrity of the skin and soft tissues can be assessed. The presence of a fluid wave, a local area of fluctuance, or a well-circumscribed area of cutaneous anesthesia may identify a Morel-Lavaleé lesion or internal degloving. To exclude the presence of an occult open fracture or an associated injury to the rectum or genitourinary tract, the surgeon must conduct thorough rectal and vaginal examinations and document the neurologic status of the limbs.

The pelvic fracture evaluation begins with the anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the injured pelvis. Although the presence of a sacral fracture may be difficult to ascertain on this film, interruption of the arcuate lines of the sacral neural foramina, avulsions of the transverse processes of L5 and/or sacrospinous or sacrotuberous ligamentous avulsions, or asymmetry of the posterior pelvis should prompt further evaluation. The 40-degree caudad (inlet) and 40-degree cephalad (outlet) projections as well as a computed tomography (CT) scan allow the surgeon to evaluate further the integrity of the anterior and posterior pelvic ring. Occasionally, obturator and iliac oblique views give further information about a posterior pelvic injury.

The method of treatment is dependent on the condition of the soft tissues as well as the fracture pattern and stability. If operative treatment is selected, the status of the posterior soft-tissue envelope must be critically assessed. If the condition of the soft tissues is unsatisfactory, then open treatment of the sacral fracture should be deferred until an exposure can be made safely through a viable soft-tissue envelope.

For most sacral fractures, surgery is usually delayed 3 to 7 days to allow the patient’s condition to stabilize, to obtain appropriate imaging studies, and to assemble the operative team. However, if the fracture is well delineated, the surgeon has all the necessary resources available, and the patient is clinically stable, surgery need not be delayed. Indications for early intervention are control of bleeding, debridement of open fractures, or a patient who requires emergent surgery for other reasons and has no contraindications to proceeding with pelvic fixation. In patients with degloving injuries, debridement of devitalized tissue or drainage of hematoma may be necessary before definitive fixation.

In general circumstances, the sacral fracture should be reduced before fixation of an associated, anterior, pelvic-ring or acetabular fracture. If only two sites of injury are found in the pelvic ring, anterior ring reduction and fixation often indirectly assists the reduction of the sacral fracture. When more than two zones of injury exist, malreduction of one component of the pelvic ring may preclude an anatomic reduction of the posterior pelvic ring or acetabulum.

For many sacral fractures, a closed reduction may be attempted because if successful, a percutaneous iliosacral-screw fixation can often be utilized. If the closed reduction is unsuccessful, however, the surgeon must be prepared to proceed with open reduction and

internal fixation (ORIF), if the soft tissues allow, rather than accept a posterior pelvic-ring malreduction.

internal fixation (ORIF), if the soft tissues allow, rather than accept a posterior pelvic-ring malreduction.

Technique for Open Reduction

Surgery is performed with the patient under general anesthesia in the prone position on a radiolucent table. The thorax is supported on bolsters, and the face is appropriately positioned and padded. Pillows are placed beneath the thighs to equal the height of the bolsters. This prevents loss of lumbar lordosis and a flexed position of the pelvis, which makes obtaining and interpreting oblique radiographic projections difficult. The pelvis itself is not directly supported because bolsters pressing directly against the anterior superior spines may be a deforming force on the pelvic ring. The knees are flexed and the tibiae rest on a padded support (Fig. 40.1). Hip extension and knee flexion relax the sciatic nerve as well as improve safety when access through the greater sciatic notch is needed. The surgical field should include the entire pelvis, including the contralateral posterior–superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the ipsilateral greater trochanter, for possible placement of distractors or clamps. The patient is not routinely placed in skeletal traction because it often rotates the pelvis rather than contributes to the reduction. Likewise, the use of a perineal post may be a deforming force against the anterior pelvic ring and may result in difficulty obtaining an anatomic reduction of the posterior injury.

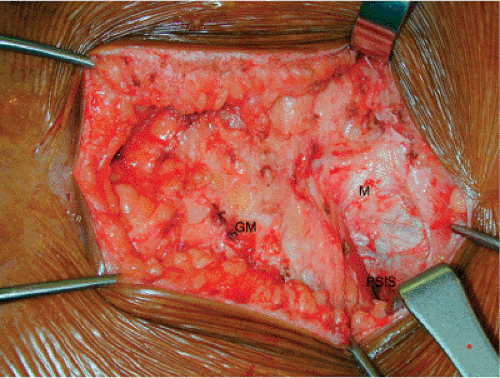

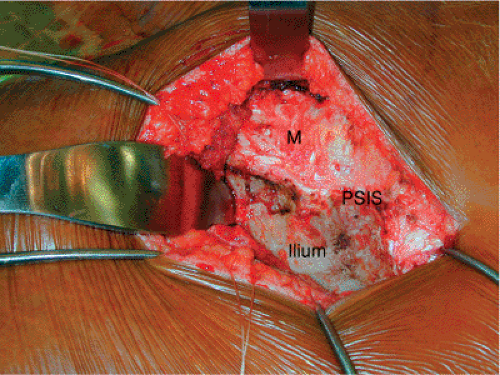

A vertical incision is made 2 cm lateral to the palpable PSIS (Fig. 40.2). The subcutaneous tissue is incised down to the fascia of the gluteus maximus muscle. The gluteus maximus muscle must be reflected laterally so that its neurologic and vascular supplies are preserved. The gluteus maximus originates from the posterior iliac crest, the fascia of the multifidus, and the spinous processes of the sacrum. Failure to release the maximus from its origin will result in an obligatory devascularization and denervation of any muscle left behind. Although fasciocutaneous flaps are generally preferred, elevating the gluteus fascia off the muscle belly can make repair of the maximus muscle impossible. The subcutaneous tissue is elevated medially off of the surface of the maximus fascia to the origin of the muscle, and the maximus is then elevated subperiosteally from the ilium and sharply off of the multifidus fascia (Fig. 40.3). The maximus can be elevated as far laterally as needed for

exposure but in most circumstances need not be elevated much beyond the crista gluteae (Fig. 40.4).

exposure but in most circumstances need not be elevated much beyond the crista gluteae (Fig. 40.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree