Pelvic Fractures: External Fixation and C-Clamp

Enes M. Kanlic

Hector O. Pacheco

Indications/Contraindications

Injuries to the pelvic ring range from simple stable fractures as the result of low-energy forces to life-threatening injuries with hemodynamic instability. The incidence of pelvic fractures in Sweden is approximately 37 per 100,000 patients per year (1). Pelvic fractures account for 3% to 8% of all fractures seen in the emergency room but are present in up to 25% of multiply injured patients. Mortality rates in patients with complex pelvic fractures and associated visceral injuries can be as high as 20% to 25%, and for patients with open pelvic fractures, the mortality rate ranges from 15% to 50% (1,2,3,4,5,6).

Of the several classification schemes for pelvic fractures, we favor the Tile classification, which is used to predict instability in the injured pelvic ring. Tile A injuries are stable fractures that can be managed nonoperatively. Tile B injuries are rotationally unstable but vertically stable. Tile C injuries are both rotationally and vertically unstable.

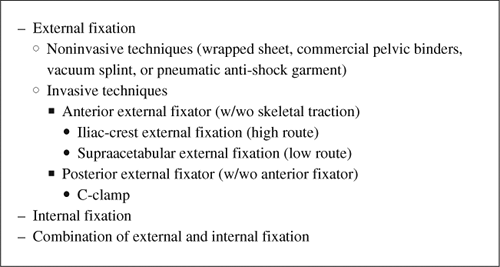

External fixation is utilized primarily in the management of patients with hemodynamic instability following pelvic fractures. Specific indications for anterior external fixation include selected, rotationally unstable, Tile B1 and B2 pelvic fractures. We strongly favor external fixation following fracture when the local conditions in and around the pelvis or abdomen are contaminated, such as with open fractures, diverting colostemies or a suprapubic urinary catheter must be placed. In addition, patients with concomitant visceral injuries, especially those whose injuries would be exacerbated when the abdomen is open, are often treated with pelvic external fixation. Occasionally, anterior-ring external fixation is used to augment posterior ring fixation.

The most common indication for anterior-ring external fixation is in a critically ill, unstable patient with a translationally unstable pelvic injury (Tile C). A resuscitative frame with ipsilateral supracondylar traction is used when a C-clamp is unavailable or not applicable.

Contraindications to external fixation are stable pelvic-ring injuries (Tile A) and patients with associated fractures of the iliac wing in which stable pin placement would be difficult or impossible. External fixation should be avoided when internal fixation can be performed on a stable patient in a timely fashion.

Preoperative Planning

Patient Stabilization

In the field or emergency room setting, emergency care workers and paramedics trained in advanced trauma life support (ATLS) often play a critical role. In patients with hemodynamic instability and a potentially unstable pelvic-ring injury, a single attempt at reduction should be considered. The responder applies traction to the unbroken lower extremity on the shortened or deformed side of the pelvis with manual lateral compression on the iliac wings or greater trochanters. The knees and ankles should be slightly flexed and internally rotated and taped together before a noninvasive external fixation device (wrapped sheet or pelvic binder) is applied (Fig. 37.1). When done at the scene of an accident, emergent transfer to an institution capable of treating pelvic trauma may be life saving (7,8).

Hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic ring injuries require prompt evaluation and simultaneous aggressive resuscitation. Initial measures include airway control and aggressive fluid resuscitation through two 14- to 16-gauge intravenous catheters in the upper extremities. Physical examination should be directed for signs of possible mechanical instability of the pelvis. Tell-tale signs include a history of high-energy trauma from motor vehicle or motorcycle collisions, falls from a height, or rollover motor-vehicle collisions. On clinical examination, a shortened and malrotated extremity, asymmetric iliac spines, swelling or blood on genitals and perineum, contusion or ecchymosis in the lower abdomen or pelvis suggest pelvic instability. Gentle, manual, iliac-wing compression from lateral toward the midline may reveal a mobile hemipelvis and mechanical instability. A careful neurological examination to assess for leg sensation and motor function is critical. Vaginal and rectal digital exams with guaiac test for occult blood and with speculums (time permitting) help rule out an occult open fracture. If overlooked and not treated, a fracture hematoma that comes in contact with a contaminated environment may cause a life-threatening pelvic infection.

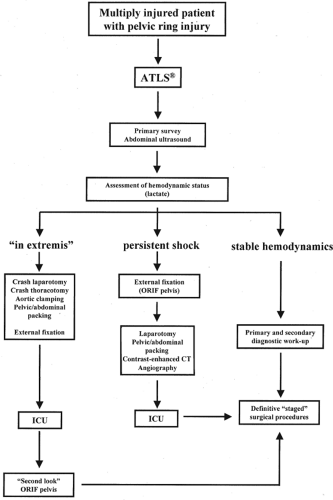

The care of a hemodynamically unstable patient with a displaced pelvic fracture is the responsibility of a multidisciplinary trauma team that includes a general surgeon, anesthesiologist, orthopedic surgeon, and invasive radiologist. Trauma protocols are helpful in evaluating and treating critically ill patients, establishing priorities, and guiding treatment. Using the algorithm (Fig. 37.2), Ertel et al (9) were able to save 15 of 20 patients (75%) who presented with multiple injuries that included unstable pelvic injuries with an average Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 41.2 ± 15.3. Fifteen patients had massive hemorrhage (14 were in extremis), and five were in hemorrhagic shock. Two of them required subdiaphragmatic clamping of the aorta to stabilize a disastrous hemodynamic situation.

As part of the primary survey, a focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) or computed tomography (CT) scan can be used to determine the presence of free fluid in intraperitoneal,

retroperitoneal, or pericardial cavities. Arterial blood gas with blood lactate levels and/or base deficit analyses are good indicators of the hemorrhagic state and tissue oxygenation (9,10,11).

retroperitoneal, or pericardial cavities. Arterial blood gas with blood lactate levels and/or base deficit analyses are good indicators of the hemorrhagic state and tissue oxygenation (9,10,11).

A chest x-ray is an important part of the trauma work-up because it can be used to rule out a pneumothorax, hemopneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, or flail chest. A single

anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis can be used to diagnose a pelvic fracture correctly in approximately 90% of cases. X-ray signs of instability are (a) >5-mm displacement of the sacroiliac (SI) joint in any plane (inlet and outlet views will improve accuracy if circumstances allow), (b) posterior fracture gap, and (c) avulsions of the transverse process of fifth lumbar vertebra or avulsion fractures of the sacrospinous ligament. By definition, a stable pelvic injury can withstand normal physiologic forces without abnormal deformation. The surgeon should not routinely manual test for pelvic ring stability because he/she could dislodge blood clots in a hemodynamically unstable patient. One-time manual testing, to exclude a situation in which the pelvis had been unstable but has since been reduced, may be permissible by an experienced surgeon in cases where the x-rays do not clearly demonstrate an unstable injury (12,13).

anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis can be used to diagnose a pelvic fracture correctly in approximately 90% of cases. X-ray signs of instability are (a) >5-mm displacement of the sacroiliac (SI) joint in any plane (inlet and outlet views will improve accuracy if circumstances allow), (b) posterior fracture gap, and (c) avulsions of the transverse process of fifth lumbar vertebra or avulsion fractures of the sacrospinous ligament. By definition, a stable pelvic injury can withstand normal physiologic forces without abnormal deformation. The surgeon should not routinely manual test for pelvic ring stability because he/she could dislodge blood clots in a hemodynamically unstable patient. One-time manual testing, to exclude a situation in which the pelvis had been unstable but has since been reduced, may be permissible by an experienced surgeon in cases where the x-rays do not clearly demonstrate an unstable injury (12,13).

Numerous studies have shown that in patients with multiple injuries, exsanguination and closed head injury are the main causes of mortality within the first 24 hours after injury. Damage control surgeries, for hemorrhage control, decompression of body cavities such as in the chest and head, and contamination control of abdominal perforations, as well as devitalized tissue debridement in the extremities, improve survival. Determination of the patient’s hemodynamic status and initial response to resuscitation measures allow placement of the patient in one of three protocol categories that dictate treatment (see Fig. 37.2).

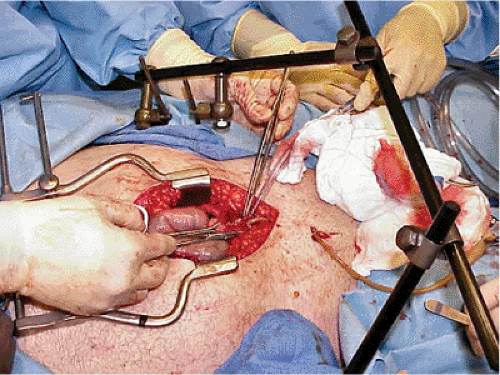

A subset of multiply injured patients presents in extremis (i.e., without measurable vital signs). Most of these patients need a crash laparotomy, thoracotomy, and/or pelvic/abdominal packing (with or without temporary aortic cross-clamping) to survive (Fig. 37.3). While awaiting the response of the patient to aggressive resuscitation therapy, a C-clamp or an anterior, pelvic, external fixator should be applied. Subsequent, repeated, pelvic/abdominal packing against a firm stabilized pelvis will be much more effective in tamponading the bleeding.

If the patient is in a persistent shock category despite adequate fluid replacement, blood transfusions, and medications over 2 hours, an external fixator or C-clamp should replace a pelvic sheet or binder. Numerous studies have shown that in patients with unstable pelvic injuries in which ligaments and fascial planes that support the pelvic floor have been disrupted, self-tamponade rarely occurs (14). Huittinen and Slätis (15) have estimated that 80% to 90 % of bleeding following fracture and/or dislocation comes from disruption of the lumbosacral venous plexus and fracture bone surfaces and that only 10% have an arterial origin. The most common technique for stopping the diffuse bleeding (venous or arterial small vessels) is by tamponade. In patients who require abdominal exploration, laparotomy

will make the pelvis more unstable because the muscle forces pulling on the iliac wings are diminished (16). A correctly applied pelvic frame will improve pelvic stability yet not impede the surgeon’s ability to perform either a supraumbilical laparotomy (from xiphoid process to symphysis for positive intra-abdominal fluid) (Fig. 37.4) or infraumbilical (absent intraperitoneal injury). If a patient with an unstable pelvic fracture requires a laparotomy for intraperitoneal injuries, exploration and packing to control retroperitoneal bleeding may be accomplished as well. Disruption of the soft tissues in the pelvic floor allows easy, direct access to both sides of sacrum and bladder for packing (17). Major arteries and veins (external iliac and femoral) that are damaged also require direct access and surgical hemostasis. In massive retroperitoneal bleeding caused by blunt trauma, Ertel et al (9) recommended that the hematoma in the central zone be explored. This method also allows assessment of the posterior reduction by direct manual palpation from inside the pelvis. Bleeding is better controlled when the bone surfaces or joint are directly opposed (interdigitating) and compressed. If significant displacement exists, loosening and adjusting the external fixator, previously applied to improve the fracture reduction, can be performed. To achieve firm local compression against the reduced posterior pelvis, the surgeon may need to repeat the tamponade and look quickly again for any major bleeding sources. If hemodynamic instability persists despite all measures (including partially closed distal-abdominal fascia for better support of packing), then the patient should be transferred for a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. The study is fast and highly accurate in determining the presence or absence of ongoing pelvic hemorrhage (18). Patients with visualized contrast extravasation, as shown on CT scans, are candidates for angiography and embolization. Following a similar protocol, the Hannover Trauma Center was able to reduce mortality rate from 46% to 25% (8,10,15,17,19).

will make the pelvis more unstable because the muscle forces pulling on the iliac wings are diminished (16). A correctly applied pelvic frame will improve pelvic stability yet not impede the surgeon’s ability to perform either a supraumbilical laparotomy (from xiphoid process to symphysis for positive intra-abdominal fluid) (Fig. 37.4) or infraumbilical (absent intraperitoneal injury). If a patient with an unstable pelvic fracture requires a laparotomy for intraperitoneal injuries, exploration and packing to control retroperitoneal bleeding may be accomplished as well. Disruption of the soft tissues in the pelvic floor allows easy, direct access to both sides of sacrum and bladder for packing (17). Major arteries and veins (external iliac and femoral) that are damaged also require direct access and surgical hemostasis. In massive retroperitoneal bleeding caused by blunt trauma, Ertel et al (9) recommended that the hematoma in the central zone be explored. This method also allows assessment of the posterior reduction by direct manual palpation from inside the pelvis. Bleeding is better controlled when the bone surfaces or joint are directly opposed (interdigitating) and compressed. If significant displacement exists, loosening and adjusting the external fixator, previously applied to improve the fracture reduction, can be performed. To achieve firm local compression against the reduced posterior pelvis, the surgeon may need to repeat the tamponade and look quickly again for any major bleeding sources. If hemodynamic instability persists despite all measures (including partially closed distal-abdominal fascia for better support of packing), then the patient should be transferred for a contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. The study is fast and highly accurate in determining the presence or absence of ongoing pelvic hemorrhage (18). Patients with visualized contrast extravasation, as shown on CT scans, are candidates for angiography and embolization. Following a similar protocol, the Hannover Trauma Center was able to reduce mortality rate from 46% to 25% (8,10,15,17,19).

In most North American trauma centers, if evidence of intra-abdominal free fluid is not found on ultrasound exam or diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) after noninvasive pelvis stabilization, angiography and embolization of identifiable bleeding arteries is usually the next step. Angiography does not address venous bleeding, is time consuming (which is particularly problematic for a patient in hemorrhagic shock), and may cause gluteal muscle necrosis. In addition, only 3% to 5% of patients with unstable pelvis receive major benefit from the procedure, which requires specialized personnel and equipment (13,20,21,22).

In a very small subgroup of patients, hemipelvectomy may be life saving (20,23). High-energy pelvic injuries that are concomitant with a major vessel injury (e.g., to the common external iliac or femoral artery), which are characterized by lack of blood flow to the extremity, and a profound neurologic deficit (and/or intraoperative finding of stretched and ruptured nerves) cause such persistent hemodynamic instability that reconstruction attempts are futile.

Open fractures with wounds in the rectal or vaginal vicinity require irrigation and debridement,

a diverting colostomy placed as far as possible from subsequent surgical approaches to the pelvis, and immediate distal-colon washout. In addition, a broad spectrum of prophylactic antibiotics should be given (2,3,4,5,6).

a diverting colostomy placed as far as possible from subsequent surgical approaches to the pelvis, and immediate distal-colon washout. In addition, a broad spectrum of prophylactic antibiotics should be given (2,3,4,5,6).

Figure 37.4. Laparotomy following application of an anterior external-fixation device. A C-clamp is covered by sheets. |

Every male patient with an unstable pelvic injury (with or without blood on ureteral meatus) requires a retrograde urethrogram before bladder catheterization. In our experience, a rectal exam cannot reliably predict the position of the prostate and possible urethral injury. A urethral injury in this setting is usually treated with a suprapubic catheter inserted percutaneously or openly during laparotomy. Patients with hematuria and intact urethra must undergo a contrast study to rule out a bladder rupture. If no explanation for hematuria is identified, an abdominal CT and intravenous pyeolography is used to investigate the upper urogenital tract. In a polytrauma patient, routine CT scans without contrast will show a ruptured kidney perirenal hematoma; contrast may be contraindicated with kidney damage or poor function. If an emergent invasive radiology procedure is contemplated, contrast studies (urological and gastrointestinal) should be done after angiography (13,20).

Pelvic Stabilization

Critically ill patients with unstable pelvic injuries require early pelvic stabilization to improve fracture stability, provide a tamponade effect, improve clotting, and reduce pain. In patients with multiple injuries, including life-threatening conditions, the speed and safety of pelvic stabilization is more important than the initial accuracy of reduction or sophistication of frame constructs.

Noninvasive Methods

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree