Pediatric Proximal Humerus Fractures

Craig P. Eberson

DEFINITION

Proximal humerus fractures (physeal and metaphyseal) are common in the pediatric population.

Most of these injuries can be treated nonoperatively because of the significant remodeling potential.

Certain fractures will require operative treatment, however, due to decreased remodeling capacity in the older child or fractures with open or threatened skin.

Aggressive surgical treatment for these injuries is rarely indicated for most children.

ANATOMY

The proximal humeral physis is responsible for 80% of humeral growth. It remains open usually until age 14 to 17 years in girls and age 18 years in boys.

A major portion of the physis is extracapsular and vulnerable to injury.

The anterior periosteum is usually thinner than the posterior, often leading to hinging of the fragments posteriorly and possible entrapment of the periosteum anteriorly.

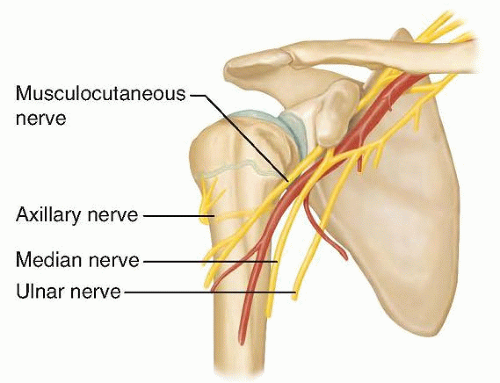

The proximal humerus lies in close proximity to the brachial plexus and axillary vessels. Care should be taken to document function of the innervated musculature before initiating treatment (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

Injuries to the proximal humerus occur from either a direct blow to the region or indirect trauma, such as a fall onto the outstretched hand.

FIG 1 • Relationship of the brachial plexus and axillary artery to the proximal humerus. The axillary nerve wraps around the humerus to insert into the deltoid, roughly 5 cm distal to the acromion.

In cases of pathologic fractures through bone cysts, throwing a ball or reaching overhead can precipitate an injury.

NATURAL HISTORY

Because of the significant remodeling potential in young children, most patients will heal without sequelae from fractures of the proximal humerus or clavicle.

Morbidity from associated injuries, however, may be significant and thus a thorough evaluation is of paramount importance.

General guidelines are available to define acceptable healing alignment for proximal humeral fractures (Table 1).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

History should include mechanism of injury, antecedent pain, and neurologic symptoms in the hand and arm.

A high-energy injury should also prompt a full trauma workup using standard Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols.

Physical examination begins with a thorough assessment of the skin for areas of compromise, particularly with associated clavicle fractures.

A neurologic examination to include the brachial plexus distribution, as well as a vascular examination of the arm, is necessary.

Neurologic injury in conjunction with fracture may signify ongoing compression (ie, sternoclavicular dislocation) and may affect prognosis.

A high suspicion for vascular injury is important in preventing late sequelae.

Table 1 Acceptable Angulation for Proximal Humeral Fractures | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

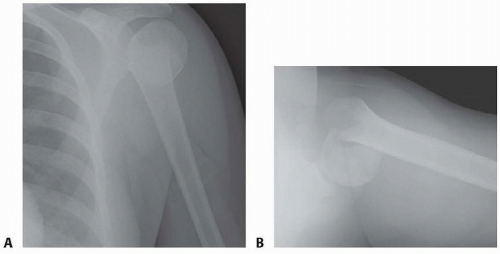

Standard initial views of the shoulder should include a true anteroposterior (AP) view, a “shoot-through” lateral, and an axillary lateral view (FIG 2).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Proximal humerus metaphyseal fracture

Proximal humerus physeal injury

Shoulder dislocation

Acromioclavicular fracture-dislocation

Sternoclavicular fracture-dislocation

Child abuse

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most of these injuries can be treated nonoperatively.

For proximal humeral fractures with acceptable alignment, treatment consists of sling management for comfort for several weeks, followed by a home range-of-motion program and return to activities in 6 to 8 weeks.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

For physeal or metaphyseal fractures of the proximal humerus, operative treatment should be considered for fractures with unacceptable residual displacement.

Closed reduction is often unstable and fixation is desirable.

Because of open growth plates, standard plate fixation techniques are rarely indicated.

Threaded wire fixation provides sufficient temporary fixation to allow healing.

Intramedullary elastic nailing is another option for these fractures.

Failure to obtain a satisfactory closed reduction may require an open reduction, and surgeons should be familiar with this technique as well.

Interposition of the biceps tendon has been noted to be the most common cause of a failed closed reduction,3 but other authors disagree.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree