Pediatric Fractures

Garrick A. Cox

Robert L. Kalb

HOW TO RECOGNIZE FRACTURES

The diagnosis of a fracture in a child may be difficult. Often, radiographs do not show a fracture, and the diagnosis is made clinically by point tenderness over the growth plate. If point tenderness is located over a growth plate, a fracture is present. The purpose of doing an x-ray is to determine if the fracture is displaced or not.

The indication for obtaining an x-ray in an adult or a child is point tenderness over the bone, deformity, and inability to bear weight on the injured extremity. If a patient does not have point tenderness over the bone at the site of injury and there is no pain associated with weight bearing, a radiograph is not required.

In children, ligaments are stronger than the growth plate cartilage (physis or epiphysis). The growth plate should be thought of as the weakest link, designed to fail first. The physis will crack before a ligament tear can occur in children. For this reason, one should not make a diagnosis of a sprain in a child.

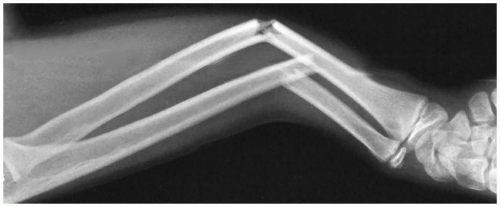

BONE

Children’s bones are elastic, similar to a plastic fly-swatter handle. Their bones can be deformed and bow without cracking the cortex. This “plastic” deformation occurs in the radial and ulnar shafts during forearm injuries. This is commonly referred to as a both-bone forearm bow fracture. It is seen in children younger than 3 years of age, when the bones are the most malleable. Pediatric bones can also bow enough to crack only one cortex. This is referred to as a green-stick fracture. (If you try to break a green branch off a tree, it may only break on one side, hence the term green-stick.)

If you are ever in doubt about the normal alignment of the forearm, remember that the ulna is always straight, and there is a small 10- to 20-degree dorsal bow present normally in the radius. You can also determine normal alignment by obtaining a comparison radiograph of the normal uninjured side. Always make sure that the views are taken with the arms in the same position of rotation, flexion, and extension for accurate comparison. Comparison views are important when treating any elbow injury because of the numerous centers of ossification in the elbow that develop through age 15 years.

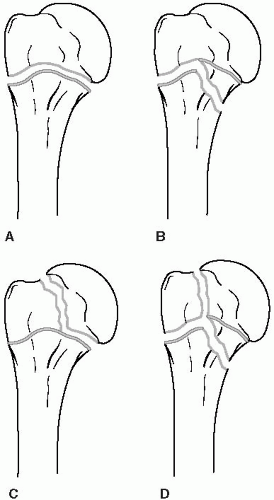

SALTER-HARRIS CLASSIFICATION

The Salter-Harris classification system (Fig. 1) is based on fracture patterns to the growth plate. The end of a long bone is the epiphysis. The growth plate is the epiphyseal plate (physis). The flare of the bone below the physis is the metaphysis. The shaft of the bone is the diaphysis.

Salter-Harris Type I

Salter-Harris type I is a fracture through the physis; the x-ray is normal. This fracture type is diagnosed by point tenderness over the growth plate. These fractures are common in infants and young children. Treatment is a cast.

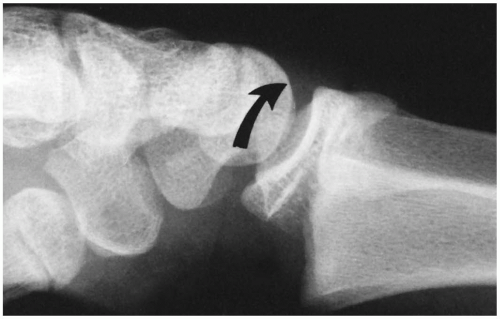

Salter-Harris Type II

The Salter-Harris type II fracture pattern (Fig. 2) involves a fracture line that crosses the growth plate and exits the metaphysis. These fractures are more common in older children. The prognosis for growth disturbance is highest when it involves the distal femoral growth plate. These fractures are displaced and should be referred. An orthopedic referral for operative reduction under general anesthesia is warranted.

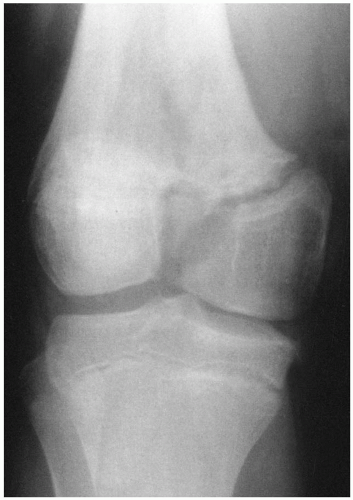

Salter-Harris Type III

The Salter-Harris type III fracture (Fig. 3) involves the epiphysis and the epiphyseal plate. This is an intraarticular fracture, and if there is any displacement, operative intervention is necessary. These are most commonly seen in the distal tibia and have a higher association with growth arrest than the previous two fracture types. Anatomic reduction is the goal.

Salter-Harris Type IV

As in Salter-Harris type III fractures, Salter-Harris type IV injuries are intraarticular and need to be anatomically aligned. If the fracture appears nondisplaced but there is question of displacement, an orthopedist should be consulted to view the film.

Figure 2 Dorsally displaced physeal fracture (type A). The distal epiphysis with a small metaphyseal fragment is displaced dorsally (arrow) in relation to the proximal metaphyseal fragment. |

Figure 3 Salter-Harris type III fracture separation of the distal femur. Note the vertical fracture line extending from the growth plate distally into the intercondylar notch with displacement. |

ABUSE

Any suspicious history indicating child abuse should be investigated by taking long-bone radiographs of the upper and lower extremities. These films should be inspected for signs of fractures in various bones at different stages of healing. A corner fracture is commonly associated with child abuse. This fracture is located at the corner of the metaphysis of long bones. These are most often seen around the distal femur and proximal tibia. Other fractures that are linked with abuse are humerus, femur, and rib fractures.

REFERRING CHILDREN WITH FRACTURES

As with adult bone injuries, children with any open fractures should be referred to an orthopedist. An open fracture may be associated with only a small puncture wound in the skin. This puncture wound may be located several inches from the fracture itself due to the forces of deformation at the time of injury. Children with fractures involving the spine or knee should also be referred because of the high risk of neurologic injury and growth plate arrest. You should always obtain comparison views for any fracture about the elbow. Because the elbow has delayed centers of ossification, refer patients to an orthopedist to review the films. Children who have any fractures with intraarticular displacement should be referred.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree