Pectoralis Major Transfer for Long Thoracic Nerve Palsy

Paul J. Cagle Jr.

Raymond A. Klug

Bradford O. Parsons

Evan L. Flatow

DEFINITION

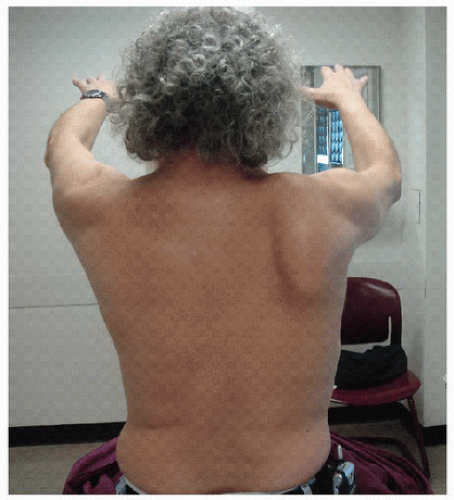

Long thoracic nerve palsy leads to classical medial scapular winging because of weakness of the serratus anterior muscle (FIG 1).

Other types of winging include trapezius lateral winging and rhomboid winging.

Lesions of the long thoracic nerve can range from paresis to complete paralysis, leading to varying degrees of shoulder dysfunction.

The serratus anterior muscle functions to stabilize the scapula against the chest wall, thus providing a fulcrum for the humerus to push against while moving the arm in space.4,6

Without this fulcrum, shoulder elevation is weakened, which leads to inability to use the arm in forward activities.

Forward elevation of the shoulder is most severely affected, followed by shoulder abduction.

ANATOMY

The serratus anterior is a large broad muscle that covers the lateral aspect of the thorax. It has digitations that take origin from the upper nine ribs, pass deep to the scapula, and insert on the medial aspect of the scapula.19

The muscle has three divisions.7

The first division consists of one slip and takes origin from the first two ribs. This division runs slightly upward and inserts on the superior angle of the scapula.

The second division is made up of three slips from the second, third, and fourth ribs and inserts on the anterior surface of the medial border of the scapula.

The third division, which consists of the inferior five slips from ribs five through nine, inserts on the inferior angle of the scapula. Because this division has the longest course, it has the longest lever arm and the most power for scapular rotation.

The serratus anterior muscle stabilizes the scapula against the chest wall, creating a fulcrum for the proximal humerus to lever against while moving the arm in space.

The serratus anterior protracts and upwardly rotates the scapula.

Its direction of pull brings the inferomedial border of the scapula anteriorly. The inferior border of the scapula is pulled forward with forward elevation of the arm. This causes the glenoid to tip posteriorly and allow full forward elevation without impingement.

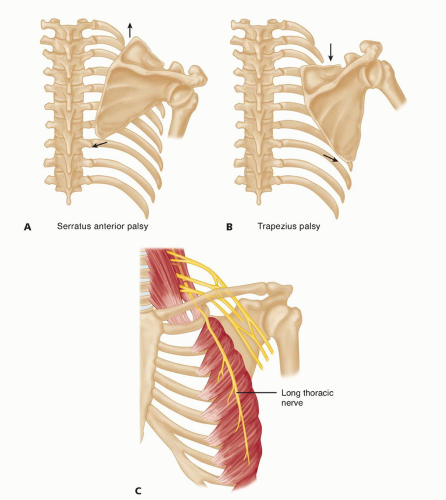

With weakness of the serratus anterior muscle, the scapula translates superiorly and medially, and the inferior border rotates medially and dorsally (FIG 2A).

The serratus anterior muscle is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which arises from the ventral rami of cervical roots C5-C7.

The C5 and C6 roots pass through the scalenus medius muscle and merge before they receive a branch from C7.

The nerve enters the axillary sheath at the level of the first rib and travels posteriorly in the axilla.

The total length of the nerve is about 24 cm, and there are several possible points of injury.

Proximally, as well as distally along the chest wall, the nerve is susceptible to injury because of its superficial location.

The nerve is tethered in the axillary sheath, which places it on stretch with forward elevation of the arm.

Cadaveric examination illustrated a fascial sling with the potential to cause nerve bowstringing with abduction and external rotation. The band extends from the inferior aspect of the brachial plexus to just superior to the middle scalene muscle.5

PATHOGENESIS

Scapular Winging

Scapular winging may be due to primary, secondary, or voluntary causes.10

Primary scapular winging can be divided into neurologic, bony, and soft tissue types.

Neurologic disorders, which are most common, include the following:

Long thoracic nerve palsy (serratus anterior weakness)

Spinal accessory nerve palsy (trapezius weakness)

Dorsal scapular nerve palsy (rhomboid weakness)

FIG 2 • A,B. Resting position of the scapula with serratus anterior and trapezius palsy. C. Superficial location of the long thoracic nerve.

Trapezius weakness winging may be distinguished from serratus winging by the position and direction of scapular laxity (see FIG 2A,B).

Bony abnormalities include osteochondromas of the scapula or fracture malunion.

Soft tissue disorders include the following:

Soft tissue contractures can cause winging.

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy represents an autosomal dominant disorder linked to chromosome 4q35 causing muscular weakness predominately of the face, shoulder girdle, and arms.

Congenital absence or traumatic rupture of the parascapular muscles

Scapulothoracic bursitis

Secondary winging may occur following disorders of the glenohumeral joint. The most common causes are multidirectional and posterior instability.

The sequence of events leading to secondary scapular winging due to primary shoulder pathology is as follows:

Primary glenohumeral or subacromial pathology, leading to

Limited glenohumeral motion, leading to

Increased compensatory scapulothoracic motion, leading to

Increased demand on periscapular muscles, leading to

Fatigue of periscapular muscles—serratus, trapezius, and rhomboids—leading to

Secondary scapular winging

Voluntary winging may occur in psychiatric patients or for secondary gain.

Long Thoracic Nerve Palsy

Long thoracic nerve palsy is the most common cause of serratus dysfunction resulting in symptomatic scapular winging, especially in those patients who fail nonoperative management and are being considered for pectoralis tendon transfer.1

Long thoracic nerve palsy has been reported to result from idiopathic, iatrogenic, viral, compressive, or traumatic (blunt or penetrating) causes.19

Most injuries are neurapraxic due to blunt trauma.

Lesions also may occur through entrapment of the fifth or sixth cervical roots at the level of the scalenus medius, during traction over the second rib or with traction and compression at the inferior angle of the scapula with general anesthesia or prolonged abduction of the arm.

Iatrogenic injuries may occur during radical mastectomy, first rib resection, transaxillary sympathectomy, or during surgical positioning.8

Other less common causes include viral illnesses, Parsonage-Turner syndrome, isolated long thoracic neuritis, immunizations, or C7 nerve root lesions.

Often, the cause is idiopathic, with a questionable history of trauma or viral illness.

Pathoanatomy

A mechanical advantage is gained by stabilization of the scapula against the chest wall.

With loss of this mechanical advantage, forward elevation against resistance is decreased.

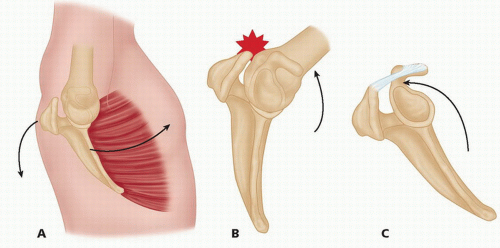

Additional types of shoulder pathology can result secondary to stabilization of the scapula:

Impingement due to relative anterior rotation of the acromion (FIG 3)

Weakness due to loss of mechanical advantage in forward elevation

Adhesive capsulitis from disuse

NATURAL HISTORY

As mentioned previously, most injuries to the long thoracic nerve are neurapraxic from stretch of the nerve or blunt trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree