Pectoralis Major Transfer for Irreparable Subscapularis Tears

Leesa M. Galatz

DEFINITION

The subscapularis is one of four muscles making up the rotator cuff. Tears can result from chronic attenuation secondary to age or overuse, but more commonly, they result from trauma.

Subscapularis tears commonly occur after a fall on the outstretched arm, traction injuries resulting in a strong external rotation force applied to the arm, or an anterior shoulder dislocation. A subscapularis tear is the most common complication after a shoulder dislocation in patients older than 40 years of age.

Many tears affect only the upper tendinous portion of the insertion. Other injuries result in a complete tear of the tendinous and muscular portions of the insertion.

Subscapularis tears are often missed early in the course of treatment. Tears older than about 6 months are usually not reparable because of atrophy and degeneration of the muscle, necessitating a pectoralis major muscle transfer.

ANATOMY

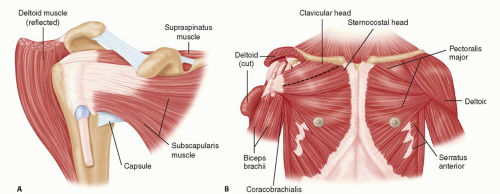

The subscapularis muscle (FIG 1A) arises from the deep, volar surface of the scapular body (the subscapular fossa) and inserts on the lesser tuberosity. The upper two-thirds of the insertion are tendinous and the lower third is a muscular insertion.

The anterior humeral circumflex artery courses laterally along the demarcation between the tendinous and muscular portions of the muscle.

Tears of the subscapularis differ from tears of the other rotator cuff muscles in that there is often an intact soft tissue sleeve across the front of the shoulder with the torn tendon retracted medially within this “sheath.” This is in contrast to tears of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus that typically leave exposed humeral head. The remaining soft tissue over the anterior humeral head after a subscapularis tear can be mistaken for an intact or partially torn tendon.

FIG 1 • A. Anterior view of the subscapularis muscle. B. Clavicular and sternal heads of the pectoralis muscle.

The pectoralis major muscle is composed of two major heads: sternal and clavicular (FIG 1B).

The clavicular head originates from the medial third of the clavicle. The sternal head originates from the manubrium, the upper two-thirds of the sternum, and ribs 2 to 4. The muscle courses laterally to insert on the lateral lip of the biceps groove.

The sternal head lies deep to the clavicular head, forming the posterior lamina, and inserts slightly superior to the clavicular head. The clavicular head forms the anterior lamina. The laminae are usually continuous inferiorly.

Some of the deep muscular fibers from the inferior aspect of the pectoralis major muscle course toward and insert on the more proximal or superior aspect of the muscle insertion. These inferior to superior directed fibers tend to make the muscle “flip” when it is released. The superior corner should be tagged to assist with orientation when used for the transfer.

The mean width of the pectoralis major insertion is 5.7 cm (range, 4.8 to 6.5 cm).7 The undersurface of the insertion has a broad tendinous insertion, whereas the anterior surface is primarily muscular; only the most distal insertion is tendinous.

The pectoralis major muscle is innervated by the medial and lateral pectoral nerves, which arise from the medial and lateral cords of the brachial plexus, respectively.

The medial pectoral nerve enters the pectoralis major muscle about 11.9 cm (range, 9.0 to 14.5 cm) from the humeral insertion and 2.0 cm from the inferior edge of the muscle.7

The lateral pectoral nerve enters the pectoralis major muscle at a mean of 12.5 cm (range, 10.0 to 14.9 cm) from the insertion.7

The musculocutaneous nerve arises from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus and enters the conjoint tendon an average of 6.1 cm (range, 3.5 to 10 cm) from the coracoid (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 9.1 cm).7

In some patients, a proximal branch enters the conjoint tendon proximal to the main branch of the musculocutaneous nerve. The function of this proximal branch is not known. It is likely innervated to the coracobrachialis, and its release has little clinical effect.

PATHOGENESIS

Subscapularis tears result from the following:

Anterior shoulder dislocations

Traction injuries to the arm with extension and external rotation forces to the arm

Rarely, chronic attenuation from age and overuse

Possible relationship to coracoid impingement

The subscapularis muscle is particularly prone to atrophy and degeneration after a tear. With complete, retracted tears of the muscle, there is a window of opportunity for about 6 months when a primary repair can be performed. Beyond that time point, the muscle is increasingly difficult to mobilize and repair is under substantial tension, leading to early failure.

NATURAL HISTORY

Subscapularis tears can result in pain, loss of motion, and loss of strength in the affected shoulder.

Failure to recognize the injury can result in a delay in treatment and possibly an irreparable tear.

An untreated rotator cuff tear can lead to progressive loss of function, stiffness, and possibly arthritis. Loss of the subscapularis may result in dynamic proximal migration of the humeral head with arm elevation that can eventually become static elevation and lead to rotator cuff tear arthropathy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Lift-off test: The patient will not be able to lift the hand off the back if the subscapularis is deficient.

Abdominal compression test: With a tear, the patient will not be able to maintain the elbow anterior to the plane of the body and will flex the wrist or hand will release from the abdomen.

Bear hug test: The patient places the hand on top of the opposite shoulder. The examiner lifts the hand off the shoulder against patient’s resistance. Weakness suggests a subscapularis tear.

Range-of-motion testing: A subscapularis tear will result in increased external rotation with the arm at the side and a “softer” end point.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A standard shoulder series of radiographs comprising a shoulder anteroposterior (AP) view, a true scapular AP view, an axillary view, and a scapular Y view is obtained to rule out fractures, arthritis, or other injury.

A subscapularis tear may result in proximal migration of the humeral head relative to the glenoid, depending on the degree of tear and involvement of other rotator cuff muscles.

In the absence of a subscapularis tear, slight anterior subluxation of the humeral head may be noted on the axillary view.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will reveal the tear and is also helpful in assessing the degree of retraction, atrophy, and fatty degeneration of the subscapularis muscle. The proximal portion of the long head of the biceps tendon becomes unstable from the intertubercular groove when the subscapularis tears. An MRI may demonstrate a dislocated or subluxed biceps tendon.

A computed tomography (CT) arthrogram is an alternative to an MRI.

Subscapularis tears can be diagnosed with ultrasound if performed by a competent, experienced ultrasonographer. Ultrasound is very sensitive for biceps tendon subluxation or dislocation from the groove.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Supraspinatus tears

Infraspinatus tears

Biceps tendon pathology

Anterior instability

Rotator cuff insufficiency secondary to neurologic etiology

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Physical therapy focusing on strengthening the intact rotator cuff muscles can be beneficial to maximize the function of remaining musculature.

Range-of-motion exercises focus on any areas of loss of motion or capsular contracture.

Rotator cuff strengthening with the use of light-resistance Therabands at waist level is an effective initial exercise. Progression to higher resistance exercises is as tolerated.

Cortisone injections may give some temporary pain relief but are unlikely to result in permanent resolution of symptoms.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication may be helpful for pain relief of mild to moderate pain.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

An attempt is made at the time of surgery to repair the native subscapularis. Within reasonable limits, the subscapularis is mobilized by releasing the surrounding soft tissues. Even a partial repair is recommended in conjunction with a pectoralis major transfer.

Surrounding soft tissues include the rotator interval and coracohumeral ligament, the anterior capsule of the shoulder (middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments), and superficial soft tissue adhesions deep to the coracoid and conjoint tendon.

The subscapularis differs from the other rotator cuff muscles in that it has a fascial sleeve that remains attached to the lesser tuberosity and covers the anterior humeral head. This is in contrast to the other rotator cuff muscles, which leave exposed greater tuberosity and cartilage without soft tissue coverage. This material is easily mistaken for an intact subscapularis, emphasizing the significance of preoperative evaluation and a high index of suspicion.

Preoperative Planning

Patient history, physical examination, and all imaging studies are reviewed. A soft tissue imaging study such as MRI or ultrasound of the rotator cuff is a necessity.

Plain films should be assessed for proximal migration, anterior subluxation, and deformity secondary to trauma and arthritis. An MRI is useful for assessing the condition of the subscapularis. A high degree of retraction and degeneration of the muscle is highly suggestive of a chronic, irreparable tear that will necessitate a pectoralis major muscle transfer.

Subscapularis tears result in instability of the long head of the biceps tendon with medial subluxation into the joint. The surgeon should be prepared to perform a biceps tenotomy or tenodesis of the tendon if it has not already ruptured from chronic, attritional changes.

Associated tears of the other rotator cuff muscles are addressed concurrently. Isolated arthritic lesions are débrided, as is degenerative labral fraying or tear.

Positioning

The pectoralis major transfer is most easily performed with the patient in the beach-chair position. The head of the bed or positioning device is elevated about 60 degrees. The head is secured to avoid cervical injury. The arm is prepared and draped free and held in a commercially available arm holder that allows flexible arm positioning.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree