Pectoralis Major Repair

Grant E. Garrigues

Matthew D. Pepe

Bradford S. Tucker

Carl Basamania

DEFINITION

Pectoralis major ruptures are injuries to the one of the largest and strongest muscles of the shoulder girdle.

Injuries can be categorized based on the location and size of the rupture.

Location: Tears most commonly occur at the tendon-bone junction but can also occur anywhere along the muscle-tendon-bone unit (including intramuscular, muscle-tendon junction, intratendinous, or as an avulsion with a fleck of the proximal humerus attached).

Size: Partial-thickness tears can affect either head. Full-thickness tears frequently involve the sternocostal head but can be a complete tear, with rupture of both the sternocostal and clavicular heads.

ANATOMY

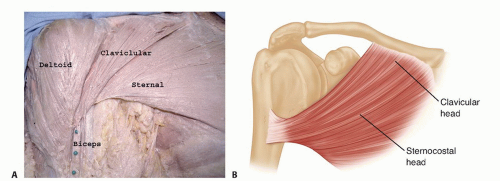

The pectoralis major is a broad triangular muscle made up of two heads. The clavicular head originates from the medial clavicle, and the sternocostal head originates from the anterior sternum, costal cartilages to the sixth rib, and external obliques.

The tendon inserts into the proximal humerus over an approximately 5-cm strip on the lateral edge of the bicipital groove.

The pectoralis major tendon has two distinct laminae, corresponding to the two heads. The tendon from the clavicular head inserts anteriorly and distally and is about 1 cm long, and the sternocostal head inserts posteriorly with a 2.5 cm long tendon.6

The sternocostal head spirals 180 degrees on itself, inserting posteriorly and superiorly to the clavicular head, creating a rolled inferior surface that is the axillary fold (FIG 1).

The function of the pectoralis major varies depending on the division. Its primary function is to adduct the humerus and its secondary role is to forward flex and internally rotate. The clavicular head primarily forward flexes and horizontally adducts. The sternocostal head internally rotates and adducts.

PATHOGENESIS

Pectoralis major ruptures typically occur during a powerful eccentric or concentric contraction during a forceful forward flexion or adduction motion of the humerus (frequently heavy bench pressing). The final 30 degrees of humeral extension disproportionally stretches the inferior fibers of the sternocostal head, putting it at a mechanical disadvantage and predisposing it to injury. The inferior fibers fail first, followed by progression toward the clavicular head.

Ruptures may also occur when a traction injury such as rapid extension, abduction, or external rotation force is applied to the extremity (such as catching oneself during a fall or during a football tackle).

Injuries to the muscle belly can also be caused by a direct blow, which can result in hematoma formation.

Patients often hear or feel a rip or tear in the shoulder region, feel a burning pain, and occasionally hear a pop.

Younger patients (younger than 30 years old) tear at the tendon-bone insertion, whereas patients older than 30 years old tend to tear at the musculotendinous junction.

Swelling and ecchymosis occur from several hours to days after the injury in the lateral chest wall, upper arm, or axilla.

Medial muscle retraction along with loss of the axillary fold may not be evident for several days until the swelling subsides.

Anabolic steroids enhance the muscle’s ability to generate force but weaken the muscle-tendon unit, making patients more susceptible to tears.4

NATURAL HISTORY

Weakness of the affected shoulder in adduction, forward flexion, and internal rotation can be expected with nonoperative treatment of full-thickness tears.

Isokinetic strength testing has demonstrated 25% to 50% deficits of strength in adduction and internal rotation in preoperative patients and people treated nonoperatively.6,7,11

Cosmetic deformity occurs secondary to the loss of the tendon in the axillary fold as well as from the medial retraction that occurs during contraction of the muscle.

Partial tears will elicit a variable degree of weakness and deformity, depending on the amount and location of tendon torn.

The initial pain and cramping that occurs during contraction of the pectoralis major usually subsides in 2 to 3 months.

Patients treated nonoperatively for full-thickness tears may complain of a cosmetic deformity as well as weakness and fatigue with vigorous recreational and occupational activities.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A previous history of pain is not typical.

The patient’s handedness, occupation, and involvement in sports and weight-lifting activities are important in decision making regarding treatment.

Use of anabolic steroids is common in this population.

Physical examination initially will yield painful range of motion of the shoulder and arm. When the swelling subsides, patients typically have full range of motion of the glenohumeral joint.

Swelling and ecchymosis are variable depending on the chronicity and the degree of the tear.

Isometric or resisted adduction and forward flexion may show the loss of the tendon contour along the anterior axillary fold and medial retraction of the pectoralis muscle. However, initial swelling can falsely make the axillary fold appear intact and obscure any defects in the contour of the pectoralis major muscle.

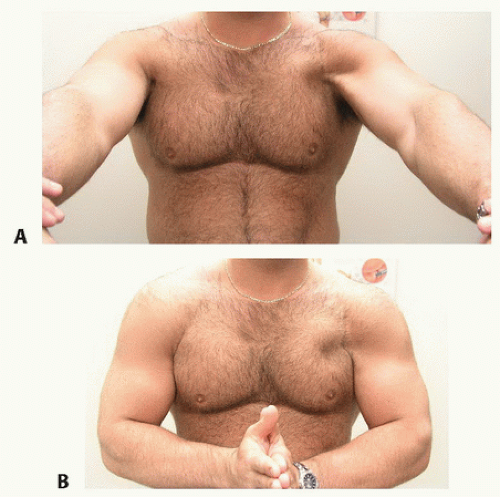

The examiner should instruct the patient to hold the arm at 90 degrees of abduction, and the anterior head of the deltoid will be accentuated. If the arm is held in forward flexion, the clavicular head will be accentuated (FIG 2A).

Directing the patient to press their hands together in front of their abdomen for isometric adduction accentuates the contour of the sternocostal head and anterior axillary fold—allowing simultaneous inspection and palpation of both sides (FIG 2B).

Manual strength testing will demonstrate weakness in adduction and forward flexion.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A standard shoulder radiographic series is obtained to rule out fractures, avulsions, or signs of instability.

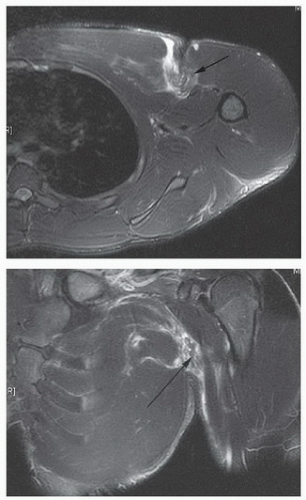

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, protocoled with a field of view large enough to include the pectoralis major, may be obtained to evaluate the location of the tear or assist in making the diagnosis.8,13 It has been shown to be beneficial in differentiating musculotendinous junction ruptures from tendinous avulsions and may change the treatment strategy (FIG 3).13

Ultrasound may be used to identify the location and severity of the tear. Results, however, are user-dependent.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment is indicated for intramuscular tears or tears at the musculotendinous junction in some people. Also, nonoperative treatment should be considered in lowdemand patients with distal tendon ruptures.

Nonoperative treatment begins with a sling for the first 7 to 10 days. Ice should be applied intermittently for the first 72 hours.

Gentle active-assisted range of motion is then begun, avoiding aggressive external rotation, abduction, or extension stretching in the initial phases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree