Abstract

Objective

To perform a systematic review of the literature regarding amputee self-care, and analyze current experts’ opinions.

Method

The research in Medline and Cochrane Library databases was performed using the keywords “amputee self-care”, “amputee health care”, “amputee education”, and “amputee health management”. The methodological quality of the articles was assessed using four levels of evidence and three guideline grades (A: strong; B: moderate; C: poor).

Result

One prospective randomized controlled study confirm the level of evidence of self-care amputee persons with grade B, which is similar others chronic diseases self-care. Self-care of amputee persons contributes to improve functional status, depressive syndrome, and also health-related quality of life. A review of the patients’ needs and expectations in self-care amputee persons has been established thanks to the presence of qualitative focus group study.

Conclusion

A multidisciplinary self-care of amputee persons can be recommended. Regarding literature date, the level of evidence of self-care amputee persons is moderate (grade B). Experts groups are currently working on a self-care amputee persons guideline book in order to standardize practicing and programs in the physical medicine and rehabilitation departments.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer le niveau de preuve de l’éducation thérapeutique des patients (ETP) amputés à partir des données de la littérature et de l’avis d’experts. L’objectif secondaire est d’évaluer les besoins en ETP des patients amputés et de les comparer aux propositions du groupe de travail SOFMER « ETP et amputé ».

Méthode

Revue systématique de la littérature avec interrogation des bases de données Medline et Cochrane Library avec les mots clés : amputee self-care , amputee health care , amputee therapeutic education , amputee health management . Sélection d’articles en langue française et anglaise sur résumés réalisée de façon indépendante par l’auteur puis lecture du texte intégral pour inclusion finale. La qualité méthodologique des articles est évaluée selon les recommandations de bonnes pratiques de la HAS en quatre niveaux de preuves et trois grades (A–C) de décembre 2010.

Résultat

L’efficacité des programmes d’ETP a été démontrée dans la littérature (grade B recommandation HAS) dans le cadre des maladies chroniques sans données pour l’amputation. La recherche spécifique et empirique a identifié 289 articles. La première sélection a en éliminé 259 sur la lecture des résumés ne retrouvant pas d’éléments traitant de l’ETP chez les patients amputés. La lecture du texte intégral des 30 articles restant a éliminé 7 articles supplémentaires. Une seule étude prospective randomisée valide le niveau de preuve d’un programme d’ETP chez des patients amputés en grade B HAS. Formalisée ou non, l’ETP permet d’améliorer le statut fonctionnel, le syndrome dépressif, et a un effet sur la qualité de vie. L’impact semble plus marqué dans la phase subaiguë post-amputation. Une revue des besoins et attentes des patients en ETP a pu être établie grâce à la présence d’étude qualitative en focus groupe.

Conclusion

Les recommandations nationales préconisent une ETP multidisciplinaire et les perspectives du rapport coût–bénéfices semblent encourageantes. Le niveau de preuve de l’ETP pour les amputés correspond au grade B HAS. La réalisation d’un guide national d’ETP prenant en compte l’ensemble des besoins répertoriés est en cours d’élaboration pour uniformiser les pratiques et programmes au sein des départements de médecine physique et réadaptation.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Amputation alters the quality of life with an undeniable negative somatic and functional impact . The patient’s general mobility is impaired and there is an increase in metabolic needs as well as pain and discomfort . Statistics on the number of amputees in France are rare and quite dated. The most commonly reported estimates are 100,000 to 150,000 amputees with an incidence of around 8000 new lower-limb amputees per year . Etiologies are quite diverse: essentially vascular pathologies (74%) for the lower limbs and trauma-related (61%) for the upper limbs . Thus, an important number of patients have to face amputation-related consequences. Pain (stump, phantom limb, back pain) is frequently described in 65 to 75% of patients after an amputation as well as the common onset of major depressive disorders for 35% of them .

Consequently, there is an increased need for care: 35% of hospitalization and outpatient consultations in this population vs. 21% for patients without amputation resulting in increased health costs. Other factors will also influence quality of life: individual ones (adaptation, cognition) and environmental ones (social and family support) .

Therapeutic education (TPE) is defined as a continuous process to help patients acquire or maintain competencies and skills needed to manage their chronic disease as efficiently as possible . TPE will enable patients to acquire the needed skills to adapt to their life after amputation. The French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SOFMER) has driven a TPE development strategy based on evidence and data from the literature, establishing recommendations, writing methodological guidelines, designing specific training programs and promoting clinical trials. This strategy already yielded several original publications . In partnership with all professionals concerned by amputation issues ( Appendix 1 ), SOFMER designed therapeutic patient education (TPE) guides according to the methodology recommended by the French National Authority for Health (HAS) (methodology guidelines on therapeutic patient education, June 2007 ).

These guides propose TPE bases to any team wanting to develop therapeutic education programs, they include guidelines and general objectives, recommendations for evaluation tools, without giving all the details of such programs, which must be adapted by PM&R teams to users in accordance with the guidelines defined by the decree dated August 2nd, 2010 (Official Journal of August 4th, 2010) for obtaining the Regional Health Agency (ARS) authorization. The effectiveness of TPE program has been validated in the literature (HAS grade B) for chronic diseases, yet to date there are no specific amputation-related data.

1.2

Objective

The main objective of this work was to determine the level of evidence regarding TPE for amputees based on evidence data from the literature and expert consensus. The secondary objective was to evaluate TPE needs in this population and compare them to the recommendations from the SOFMER “TPE and amputee” workgroup.

1.3

Material and method

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in the Medline and Cochrane Library databases, searching articles from 1966 to 2012. The references of the articles selected were taken into account and articles corresponding to inclusion criteria but not found in the initial search were also selected. A Grey Literature search was also conducted using Google Scholar, Google and Abes. Keywords used were “amputee self-care”, “amputee health care”, “amputee therapeutic education” and “amputee health management”.

A first abstract-based selection of articles was conducted independently by the author in order to retain articles on therapeutic patient education in patients who underwent amputation of the upper or lower limbs. Once the articles selected, the full texts were read thoroughly. A first reading was done to discard articles not directly related to therapeutic education after limb amputation. The following articles were kept: controlled, randomized studies, reviews or recommendations, prospective and retrospective qualitative studies, prospective and retrospective quantitative studies and descriptive studies in French and in English with at least one link between TPE and amputees.

The methodological quality of these articles was assessed based on the 2010 recommendations for best practices from the French National Authority for Health (HAS): four level of evidence and three grades (A: strong; B: moderate; C: poor) . Nevertheless, we kept studies with a poor methodological quality (inadequate, small number of subjects, lack of clarity in the interventions) due to the very low number of clinical trials and randomized, controlled studies, reviews and recommendations in the literature. Due to the lack of evidence levels, we collected the opinion of experts participating in a workgroup and common professional practices.

1.4

Results

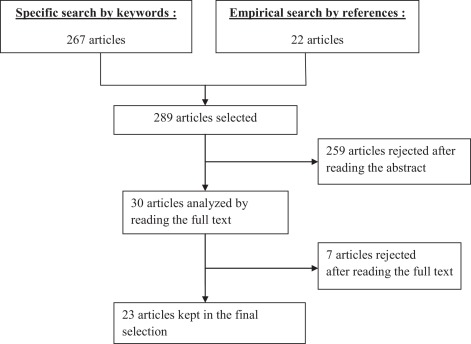

The search with specific keywords yielded 267 articles and the comprehensive search of the selected articles’ references identified 22 other articles amounting to a total of 289 articles. The first selection discarded 259 articles based on theirs abstracts since there were no specific amputation-related TPE elements. Reading the full text of the 30 remaining articles discarded 7 additional articles: 3 relating to TPE in chronic diseases but not specific to amputation , 3 that focused on modalities and prescription choice for prosthetics , and finally one on social acceptance and returning to work after amputation ( Fig. 1 ).

1.4.1

Complete description of a therapeutic patient education program for patients after amputation

Very few rigorous studies on TPE programs for amputees are found in the literature. Studies mainly describe tools associated to another therapeutic intervention, classic TPE methods such as Metaplan™ and brainstorming. The first is used for group animation and communication model. It consists in developing opinions, constructing a common comprehension and formulating objectives, recommendations and action plans before focusing on the problem and its possible solutions. The second method involves the spontaneous contribution of ideas from all members of the group, stimulating creativity to find solutions in order to solve a problem. The goal is to generate as many ideas as possible in a minimum of time on a given theme without judging or criticizing others. This group method of generating ideas privileges quantity, spontaneity and imagination. Only one study with a good methodological quality (level 2) evaluated the acceptance and effectiveness of a TPE program aimed at improving the quality of life of patients after limb loss. This prospective, comparative, cluster randomised study from the United States was published in 2009. Its main objectives were to reduce pain and depressive disorders, improve positive moods while promoting self-management capacities in the patient. Secondary objectives were to improve the patients’ functional status and quality of life.

Wegener et al. used support groups for patients with limb loss, which were already in place in the American National Health System in order to randomize and test a TPE program. All participants involved in these groups for at least 4 months and who underwent amputation of at least one limb (upper or lower limbs) were invited to join the study.

There was no significant difference between the control group and the study group regarding: age (56.9 ± 13.3 vs. 55.5 ± 13.8), gender (59% men vs. 55%), amputation etiologies (vascular/diabetes 34.8% vs. 37.1%, trauma-related 36.1% vs. 39.3%, neoplastic conditions 10.6% vs. 5.5%, congenital 1.8% vs. 3.6% and others) . Very few upper-limb amputees participated in the study (11 in the control group, i.e. 4.9% vs. 20 in the study group, i.e. 7.3%) .

When we look at the TPE approach described by the HAS, an educational diagnosis was not found in this study. The content of the program is not specifically described, but includes general presentation of TPE, pain management, psychological support (building positive emotions and managing negative thoughts), hygiene guidelines (lifestyle, stump, prosthetic) and finally interaction with family and the outside world.

The multidisciplinary education team included nurses, prosthetics/orthotics professionals and American veterans.

Patients were seen in group sessions, with a maximum of 10 persons per group. The meeting location was not indicated: it was the usual meeting place of the support group. The dedicated time was 90 minutes per session. Frequency was 1 session per week for 8 weeks followed by another session 2 weeks later. Validated scales were used to evaluate the efficacy of the program on the symptoms: pain was evaluated with the Brief Pain Inventory, depressive syndrome by the Major Depressive Disorder Scale (CESD), mood evolution by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule and Positive States of Mind scales and finally self-management was assessed by the Modified Self-Efficacy scale.

Secondary criteria were also evaluated: improvement of the functional status was evaluated by the Musculoskeletal Function Assessment – Short Form and quality of life by the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS).

The final evaluation of TPE program implementation consisted in open questions on behavioral changes. In this study, the TPE program was proposed to all patients regardless of the amputation level and clinical type.

Authors noted significant improvements on depression, mood, self-management and functional status lingering for 6 months after the end of the program. However, no significant improvement was recorded for pain and quality of life. A subgroup analysis (amputation < 3 years, age < 65 years) showed a significant improvement on all the parameters including pain and quality of life.

To our knowledge, this represents the first and only prospective, cluster randomized study evaluating the efficacy of a TPE program in patients after limb loss. It validates the grade B level of evidence of TPE program in amputees (HAS).

1.4.2

Content of TPE program and evaluation of amputee needs

The design of the various TPE program should be based on the needs brought up by patients. Five studies have been published on the needs for information and education of amputees (one level 3 study and four level 4 studies). The three first studies published in 1988 , 1989 and 1998 evaluated and discussed the role of nurses in amputee support groups while giving details on the program themes.

A 1991 study evaluated the education needed for children with bilateral limb amputation regarding personal hygiene.

Finally, a recent study published in 2009 , with a better methodological level (level 3), presented and discussed the results of an evaluation on lower-limb amputee needs assessment held in Seattle and Washington on October 30–31, 2007. Klute et al. conducted a qualitative study with a focus group approach which had three objectives: on the one hand evaluating on a qualitative level the needs, worries, interests and opinions of prosthetic users on the performances of their prosthetics; on the other hand evaluating the hypothesis that the needs of vascular and diabetic amputees are different than trauma-related amputees; and finally conducting open discussions on emerging issues that could shape the future directions of research and development for the various professions represented.

Three other studies have been published on the needs of patients faced with stump pain, phantom limb pain and musculoskeletal pain (one level 3 study and two level 4 studies). A first study from 2006 described the advances in pain management through prevention programs. A second study from 2001 found a greater prevalence of low back pain in amputees (52%) than in the general population (15 to 25%). Finally, a third study from 2000 found a similar incidence of phantom limb pain and stump pain in over 70% of amputees. Other studies (total of 8: including three level 3 studies and five level 4 studies) showed the interest of patients and healthcare professionals for the following: stump hygiene , falls prevention , prevalence and management of depression disorders and finally the relevance of physical activity on the patient’s future functional status .

Some themes underlined in the needs expressed by amputees are common to all these studies and are unquestionable: stump pain management ( Table 1 ) phantom limb pain management ( Table 1 ), musculoskeletal pain and disorders ( Table 1 ), stump ( Table 1 ) and prosthetic hygiene ( Table 1 ), grieving for the lost limb ( Table 1 ), information and education workshop on the various types of prosthetics and their modalities of use ( Table 1 ). Patients also wanted to learn about the perception of amputation and changes in social life . Daily needs were also important: couple relationship and sexuality , professional life and transportation . Patients were also in demand for more technical education regarding fitting and cleaning their prosthetic socket as well as prosthetic alignment . Other themes have been identified and should not be overlooked when designing a TPE program such as falls prevention ( Table 1 ), managing depression ( Table 1 ) and possible sports and physical activities ( Table 1 ).

| SOFMER group proposal | Data from the literature |

|---|---|

| Stump contention | Fitting and cleaning the prosthetic socket |

| Stump/prosthetic hygiene and skin issues | Stump/prosthetic hygiene |

| Amputee pain | Managing stump pain, phantom limb pain and musculoskeletal pain |

| Prosthetic fitting and managing stump volume variations | Information and education workshop on the different prosthetics and their modalities of use |

| Technical maintenance of the prosthetic | Prosthetic alignment |

| Safe use of the prosthetic and preventing falls | Falls prevention |

| Exercise and leisure activities | Education on possible sports and exercise |

| Body representation and amputation experience | Amputation representation and changes to social life |

| Managing depression | |

| Grieving for the missing limb | |

| Couple relationship and sexuality | |

| Professional life and transportation | |

| Review of existing educational supports | |

| Upper-limb specificity | |

| Managing cardiovascular risk factors |

The main actors of TPE programs found in the literature differ according to the year of the publications. The first studies insisted on the role of nurses, who are close to patients and have the type of relationship enabling the implementation of TPE programs but not necessarily in PM&R departments . More recent articles have focused on other actors involved in multidisciplinary care in PM&R departments: occupational therapists , physiotherapists but also adapted physical activity (APA) teachers and psychologists .

1.4.3

Different TPE stages for amputees

Four education stages characterize the amputation care management process :

- •

preoperative care (for vascular and diabetic amputees);

- •

hospitalization in the surgical department;

- •

hospitalization in the PM&R department;

- •

finally returning home to an active life.

Proposals formulated by Klute et al. underline the need for a targeted therapeutic education at each stage of the care management process of an amputee, including on the long-term as reminder sessions. Finally, it is interesting to note that the study did not unveil any difference between the needs and expectations of vascular/diabetic amputees and trauma-related amputees, and thus it would make sense to propose common TPE sessions.

1.4.4

SOFMER workgroup recommendations

These recommendations from the “TPE and amputee” SOFMER workgroup, based on the professional experience of experts, are quite similar to the themes found in the literature. In fact, 11 themes emerged from the discussions:

- •

stump contention;

- •

stump/prosthetic hygiene and skin issues;

- •

amputee pain;

- •

prosthetic fitting and managing stump volume variations;

- •

technical maintenance of the prosthetic;

- •

specificity of the upper limb;

- •

safe use of the prosthetic and preventing falls;

- •

physical activities and leisure activities;

- •

managing cardiovascular risk factors;

- •

body representation and amputation experience;

- •

and finally conducting a review of all the educational supports already available.

The collection and validation of experts’ opinions took place in a plenary session where everyone could propose a theme, which needed to be validated by all experts in attendance ( Appendix 1 ). Thus, the review of the literature legitimates the choice of these different themes underlined by the professional experience of experts ( Table 1 ).

1.4.5

Need for pre-amputation (non-traumatic) TPE

To conduct TPE programs before surgery, it is essential to identify the factors that could influence the patient’s personal decision (outside of a medical indication). Three studies have been published on the decision-making process of patients before amputation (one level 3 study and 2 level 4 studies). A first study dating from 2000 focused on training former patients (at a distance from their amputation) to visit patients during the preoperative period to help them with their decision-making process and answer the questions they might have. A second level 4 study from 2012 identified the decision-making factors in a qualitative manner via a standardized, retroactive, open questionnaire. Finally, one last qualitative study from 2011 listed other decision-making factors collected via standardized open-ended interviews and prospective targeted questionnaires. The aim of these studies was to understand the decision-making process of patients who chose amputation in order to help physicians and healthcare professionals provide better support and advice to their future patients.

Three key factors emerged from the two qualitative studies: pain , loss of limb function and participation restriction . Three factors were considered as being of little importance: body representation , physical identity and opinion of others . Most participants were not interested in the opinion of health care professionals and insisted that the decision was a personal one . However, participants found the information given to them useful for their decision-making process and in setting up expectations regarding their future prosthetic . Finally authors’ recommendations underlined the fact that amputation should not be viewed as a failure of previous medical treatments but as the best mean to free the patients from years of pain and suffering.

1.4.6

Therapeutic education tools

The literature offers very few descriptions of TPE tools. Regarding TPE sessions, they were all group sessions with a limited number of participants (less than 10) . The topic of the session was brought up through open questions followed by a discussion between patients and the educational staff .

Various tools were used: descriptive information sheets with illustrations on stump bandaging to hand out to patients , slide presentations to illustrate the discussions , practical workshop for prosthetic socket fitting or for using technical aids for personal hygiene .

Pain management workshops use mock prescriptions to evaluate the patient’s understanding of a medical prescription . TPE programs’ contents must by adapted to users while abiding by HAS guidelines. To our knowledge, in the literature, there is no study on the experience of French teams with description of TPE tools for amputees.

Internet has become an essential tool for informing and educating patients. To our knowledge, there is no website of reference, in French or in English, for TPE in amputees, but only information sites managed by patients’ associations.

1.4.7

Evaluation TPE tools

Therapeutic patient education programs must abide by the French national guidelines. To be implemented at a local level, these programs must first be authorized by the regional health agencies that recommend the implementation of a TPE evaluation. No tool specific to TPE in amputees has been found for this review. The TPE guide proposed by the SOFMER group will require frameworks for each therapeutic workshop but also the implementation of validated evaluation tools for each theme and these tools will be described in the guide ( Table 2 ).

| Authors | Themes | TPE intervention | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darnall et al. | Preventing depression disorders | No | Level 4 |

| Dyer et al. | Falls prevention | Yes | Level 4 |

| Hachisuka et al. | Stump hygiene | No | Level 4 |

| Jacobsen | Nurse role with amputee support groups | Yes | Level 4 |

| Klute et al. | Qualitative needs analysis of amputees | No | Level 3 |

| Marzen-Groller et al. | Physical activity | Yes | Level 3 |

| Pasquina et al. | Pain management | Yes | Level 4 |

| Schoppon et al. | Preventing depression disorders | Yes | Level 4 |

| Stepien et al. | Physical activity | No | Level 4 |

| Stineman et al. | Physical activity | No | Level 4 |

| Wegener et al. | TPE program evaluation | Yes | Level 2 |

| Yetzer et al. | Nurse role with amputee support groups | Yes | Level 4 |

| Yetzer et al. | Nurse role with amputee support groups | Yes | Level 4 |

1.5

Discussion

Even though the number of amputees is quite high, there are very few studies on TPE for patients with limb loss. Their methodology is debatable and hardly exploitable for practical clinical applications in this population. The various TPE modalities are not always clearly defined, to allow their generalization and application during the patient’s hospital stay or outpatient visits. No level 1 or grade A study has been found. The literature has validated the grade B (HAS) level of evidence of a TPE program in amputees based on a sole study conducted by Wegener et al. . The methodological quality of this study is of level 2 evidence thanks to a prospective, cluster randomization study with a satisfactory number of subjects. Because of its limits, this study cannot be classified as level 1 evidence. On the one hand, the authors did not report the intra-cluster correlation coefficient, which could have induced a selection bias for randomized patients. There is an obvious “group effect” when subjects share the same characteristics, which can limit the extrapolation of the results to the general population: i.e. similar environment, almost identical socioprofessional characteristics and maybe even sharing the same physician trained to TPE. On the other hand, Wegener et al. successfully used the American Health System characterized by support groups for amputees, first created for Vietnam (1954–1975) and Gulf war (1990–1991) veterans. Thus cluster randomization was completely legitimate. However, it would seem complicated to extrapolate this type of study to other countries, like France, which do not have these support groups. In France, the presence of patients’ associations with regular meetings (e.g. ADEPA, 3A) as well as active follow-ups by multidisciplinary teams in PM&R departments can nevertheless counterbalance the lack of these support groups. Thus, we can consider that these TPE programs for amputees and their level of evidence could be extrapolated to the French Health Care System for a successful implementation.

In light of this study, it seems essential to design amputee-specific TPE programs. They must abide by the following validated criteria (HAS, 2007): develop an educational diagnosis, conduct therapeutic education sessions, perform individual assessments of acquired competencies and coordinate all the different healthcare professionals. These programs must be developed with the input of patients or their representatives (patients’ association/caregivers). For each theme, the content of these TPE programs must result from a consensus between professionals, PM&R physicians and healthcare teams (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, psychologists, APA teacher). Teams must also implement evaluations on the short-, middle- and long-term.

This is the reason why the “TPE and amputee” SOFMER workgroup ( Appendix 1 ) includes all professionals concerned by amputation-related issues as well as representatives of patients’ associations. The objective is to design TPE guides to provide theoretical bases to teams wanting to develop TPE programs; these guides can be adapted to users. The themes were proposed based on the experience of experts attending the group meetings and validated by this literature review.

Using qualitative studies is the best possible option to study the behaviors and motivations of a group of patients. These studies are not designed to extrapolate the obtained results but rather to investigate the behaviors and feelings of amputees. Each selected theme will then be discussed in depth in subgroups headed by a physician, and then validated in plenary sessions by the entire SOFMER group before being used by multidisciplinary teams in PM&R departments.

Therapeutic education is an essential element of non-pharmacological care for patients with chronic diseases . Its effectiveness on morbidity/mortality and quality of life has been validated in the literature for the follow-up of patients with diabetes , asthma arthritis . These data have been validated for French patients for these same pathologies but also for patients with heart failure . These elements, underline the fact that conducting TPE programs will be an essential component for the comprehensive care of patients with limb loss in PM&R departments.

Due to an insufficient number of studies to validate or contradict the efficacy of therapeutic education, it is difficult to analyze its medical-economic impact. Nevertheless, it seems that such programs could help decrease the frequency of hospital stays and outpatient consultations . It is also possible to differentiate several areas in which TPE could bring clinical and economic benefits : pediatric asthma, type 1 diabetes and cardiology (except for oral anticoagulant therapy). The cost-benefit perspectives of TPE for amputees seem rather encouraging.

Finally, according to HAS recommendations , TPE programs need to be part of a global strategy to define a coherent organization and thus guarantee the success of TPE interventions. In order to achieve this, it is essential to implement coordination and resource centers similar to the ones already in place for neurological patients, i.e. post-stroke centers , but also for cardiovascular patients . The “TPE and amputee” SOFMER experts’ workgroup could fill that role and coordinate the various TPE programs in order to facilitate their implantation in France within structures that have the right competencies and necessary means.

This review of the literature was the first step to legitimate TPE for patients with limb loss and select the relevant themes to be included in future TPE programs. Soon, it will become necessary to conduct quantitative, randomized, prospective, multicenter studies to evaluate the effectiveness of this type of TPE programs and validate the contents of support documents used in this TPE. Developing a national guide will help standardized TPE practices in order to extrapolate the results to the entire population of French amputees. It would also be interesting to conduct a qualitative study on the specific TPE-related needs of French amputees just like Klute et al. for amputees in the USA. Even though the results can be extrapolated, this study will help design programs in light of the characteristics and specificities of the French healthcare system.

The need for information and education is an important part of follow-up care, like evaluating patient’s satisfaction. This has encouraged prosthetic professionals and industry representatives to distribute non-validated tools and questionnaires to these patients. There was a real need for a partnership between physicians, healthcare teams, orthotics/prosthetics professionals and industry representatives; the “TPE amputee” SOFMER workgroup answered this need by allowing the scientific supervision of TPE programs’ contents. National recommendations advocate multidisciplinary TPE, which is a characteristic of PM&R departments.

1.6

Conclusion

Based on the data from the literature as well as international recommendations, TPE must be an integrative part of amputee care management. This education aims at changing the patient’s lifestyle especially regarding physical activity or pain management. These TPE programs must be adapted to the patients, their symptoms, their needs and expectations. Additional studies are needed to better refine the contents of these educational programs, alone or associated with other therapeutics, as well as evaluating their medical-economic impact. It seems essential to validate the content of support documents used in TPE programs and develop tools dedicated to the educational evaluation of amputees. This is why the elaboration of a national TPE guide taking into account all the needs listed is underway to standardize practices and programs within PM&R departments.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Appendix 1

List of participants in the “TPE and amputee” SOFMER workgroup: PM&R physician, healthcare professionals, orthotics and prosthetics professionals, industry representatives, patients’ association representatives.

| Name | Profession | Location | Activity | Sector of activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mr. L. Auduc | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. D. Azoulay | Orthotics and prosthetics professional | Paris, France | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. B. Baumgarten | Orthotics and prosthetics professional | Nancy, France | Hospital/private practice | Public/private |

| Mrs. S. Boujard | Occupational therapist | Rennes, France | Hospital | Public |

| Mrs. S. Castelao | Registered nurse | Corbeil-Essonnes, France | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. P. Chabloz | Orthotics and prosthetics professional | Grenoble, France | Hospital/private practice | Private |

| Dr. G. Chiesa | Physician | Valenton, France | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. F. Codemard | Orthotics and prosthetics professional | Nancy, France | Hospital/private practice | Private |

| Prof. E. Coudeyre | Physician | Clermont-Ferrand, France | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. M.C. Cristina | Physician | Rennes, France | Hospital | Public/private |

| Mrs. C. Dalla Zanna | Psychologist | Clermont-Ferrand | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. M.P. Deangelis | Physician | Grenoble | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. N. De Hesselle | Physician | Issoudoun | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. T. Dubois | Physician | Cholet | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. S. Ehrler | Physician | Strasbourg | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. D. Eveno | Physician | Nantes | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. P. Fages | Physician | Granville | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. D. Fillonneau | Orthotics and prosthetics professional | Rennes | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. J.P. Flambart | Physician | Nice | Private practice | Private |

| Mr. M. Frélicot | APA teacher | Rennes | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. R. Gastaldo | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. P. Guerit | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. M. Henkel | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. J.P. Hons Olivier | Patients’ association representative | France | NA | NA |

| Dr. R. Klotz | Physician | Tour de Gassies | Hospital | Private |

| Dr. I. Loiret | Physician | Nancy | Hospital | Public |

| Dr. N. Martinet | Physician | Nancy | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. V. Mathieu | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. C. Mota | Industry representative | France | Industry | Private |

| Mr. J.L. Obadia | Patients’ association representative | France | NA | NA |

| Dr. E. Pantera | Physician | Clermont-Ferrand/Vichy | Hospital | Public |

| Prof. J. Paysant | Physician | Nancy | Hospital | Public |

| Mr. B. Saurel | Physiotherapist | Grenoble | Hospital | Public |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree