CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Osteoporosis is the commonest bone disease and is the most common and eminently preventable risk factor for fracture. In the United States, there are 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures per year, with a direct annual cost of approximately $18 billion.

1 Approximately one-half are vertebral fractures, and one-fifth are hip, wrist, and other fractures.

2 Among people surviving to the age of 90, 33% women and 17% men will have a hip fracture.

3 After the age of 50 years, a woman is three times more likely than a man to have a vertebral or hip fracture.

3 African American and Asian women have less risk of fractures compared to Caucasian women.3 Unlike osteomalacia, osteoporosis is asymptomatic till a fracture occurs. Pain and other subtle symptoms are related to fractures and consequent to deformity.

Patients who fear falling are more likely to fall and therefore more likely to fracture; therefore, fear of falling is an important history to obtain. Mortality rates are higher in patients with advanced age, restrictions in activities of daily livings (ADLs), and the presence of dementia. The majority (95%) of young (<75) vigorous patients may recover to near-normal function, while those older than 84 years, with 0 to 1 independent ADLs and dementia, have a 71% mortality. Survivors often have physical limitations that may require living quarters change, especially independent ambulation and stair climbing.

Vertebral fractures are the commonest clinical manifestations of osteoporosis. About two-thirds are asymptomatic and are discovered as an incidental finding on chest or abdominal radiographs. In women who have vertebral fracture, approximately 19% will have another fracture in the next year.

4 Unfortunately, only in 38% of cases after a first fracture is osteoporosis diagnosed, meaning that in a large number of cases, an opportunity to prevent a second fracture is missed.

5 Fractures typically occur during routine activities such as lifting or bending and can cause acute pain. This pain is replaced by a chronic pain, which may persist for a long time or eventually subside. Successive fractures can lead to thoracic kyphosis with height loss and a “dowager’s hump.” Abdominal contents are compressed into less vertebral space, which results in a protuberant belly; patients complain of weight gain, which is apparent rather than real. Patients may have early satiety or constipation as well as pain in their neck muscles as they have to constantly extend their neck. Because of kyphosis, the rib cage comes close to the iliac crests and may bounce on them, causing pain or a clunking sensation. Finally, kyphosis can also lead to dyspnea and a restrictive defect on pulmonary function testing. De Smet et al. found that solitary wedge fractures did not occur above the seventh thoracic vertebra in a study of 87 osteoporotic women. They therefore suggested that if a solitary vertebral fracture is found above the seventh vertebra, a cause other than osteoporosis must be considered.

6A meta-analysis reported that certain physical exam findings in patients who do not meet screening recommendations suggest the presence of osteoporosis or spinal fracture and warrant further workup: (a) wall-occiput distance (inability to touch occiput to wall with back and heels to wall), (b) weight <51 kg, (c) rib-pelvis distance (<2 fingerbreadths from the inferior margin of ribs to superior surface of pelvis at the midaxillary line), (d) fewer than 20 teeth, and (e) self-reported humped back.

7

SCREENING METHODS

At present, universal screening for all postmenopausal women for low bone mineral density (BMD) is

not recommended. Although numerous risk factors have been identified, it is not clear which women merit screening. National practice guidelines on postmenopausal osteoporosis screening have been created by numerous organizations, including the National Osteoporosis Foundation

8,9 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

10 the Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE),

11 and the American Academy of

Family Physicians,

12 summarized in

Table 60-1. All support an individualized approach rather than universal screening.

13

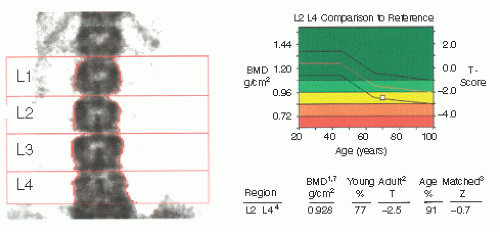

Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Scan

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), the preferred screening test, uses dual-energy photon beams to measure bone mineral content (BMC) and bone area (BA) of the L1-4 vertebrae and hip. BMD is calculated by dividing BMC by BA. A T-score, used for diagnosis of osteoporosis, compares patient BMD to a sex- and ethnicity-matched young adult. Z-scores compare patient values to age-, sex-, and ethnicitymatched peers and are recommended for patients <50 years of age. DXA is the most accurate method for detecting low BMD, is predictive of fracture risk, and is the method by which the WHO defines osteoporosis.

4 The 10-year risk of a fragility fracture in a postmenopausal woman with a T-score ≤ -2.5 is 5% at age 50 but 20% at age 65; absolute risk increases with additional risk factors such as previous fragility fractures.

14 Although it is a good predictive tool of fractures on a population level, DXA is only modestly successful on an individual basis. Of those women over 65, 7% with normal BMDs will suffer a fracture; of those with severe osteoporosis (T < 4), less than half will ultimately experience a fracture.

14,15 Furthermore, osteoarthritis, aortic arteriosclerosis, and intervertebral disk chondrocalcinosis may artifactually increase measured spinal BMD.

16 Ironically, aortic calcification is associated with lower BMD of the femur and an independent predictor of hip fracture.

17

Quantitative Computed Tomography

Another option is quantitative computed tomography that separately analyzes trabecular and cortical bone. While it can detect early vertebral bone loss quite sensitively, it has not been validated, is more costly, and has more radiation exposure than DXA.

15 Finally, peripheral densitometry, which measures radius, heel, and hand BMD, does not show good T-score correlations with those of central DXA scans.

18

Biochemical Markers

Biochemical markers for bone formation and resorption, while not meant for screening, are indicated for patients with low Z-scores and may be helpful when secondary causes of bone fragility and loss are suspected (

Table 60-2).

15 Additionally, because these markers change in response to treatment more quickly than does BMD, they may have a role in monitoring response to therapy. Derangements are associated with increased fracture risk, but there is significant variability.

ABSOLUTE FRACTURE RISK ASSESSMENT

The most significant change to the screening, prevention, and treatment of osteoporosis is the World Health Organization (WHO) FRAX instrument that calculates risk of fracture based on risk stratification in postmenopausal women and men aged 40 to 90 years. It is validated to be used in untreated patients, although in reality it can be a useful tool to determine the need

for continued treatment, especially if there has been a change in risk factors. This fracture prediction algorithm can help guide the clinician as to who should receive treatment. The current practice, based on WHO guidelines, is to treat patients who have a 10-year risk of hip fracture of >3% or 10-year risk of any fracture >10%. Additional risk factors such as frequent falls, not represented in the FRAX, warrant individual clinical judgment. To use the FRAX go to http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/ (click on Calculation Tool, and select country).

19,20