Osteochondritis Dissecans and Large Osteochondral Defects of the Knee

Kevin G. Shea

John Polousky

Noah Archibald-Seiffer

DEFINITION

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a focal idiopathic alteration of subchondral bone with risk for instability and disruption of adjacent articular cartilage that may result in premature osteoarthritis.

OCD and other traumatic injuries can lead to large osteochondral defects of the knee.

ANATOMY

Many of these injuries will include the medial or lateral femoral condyle, in both OCD and acute cartilage injury.

PATHOGENESIS

The etiology of OCD is not known, although many theories have been suggested, including trauma, vascular anomaly/injury, overuse or repetitive stress injury, genetic predisposition, etc.

Acute traumatic injuries can cause displacement of preexisting OCD lesions or the development of acutely displaced cartilage fragment on otherwise normal bone and cartilage structures.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of OCD runs a variable course.

Many patients, especially those who are skeletally immature, with significant growth remaining, have good potential for healing with appropriate activity modification, and in select cases, subchondral bone drilling.

Patients close to or beyond skeletal maturity have a worse prognosis for healing with activity modifications.

The older patients may not respond to less invasive surgeries such as subchondral bone drilling.

Patients with acute, traumatic cartilage injury with displaced fragments may be candidates for surgery.

Cases in which the cartilage damage is so severe that the fragment is unsalvageable, osteochondral defects may be addressed with a variety of cartilage restoration procedures.

This chapter focuses on the use osteochondral allografts to address these large, irreparable defects.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

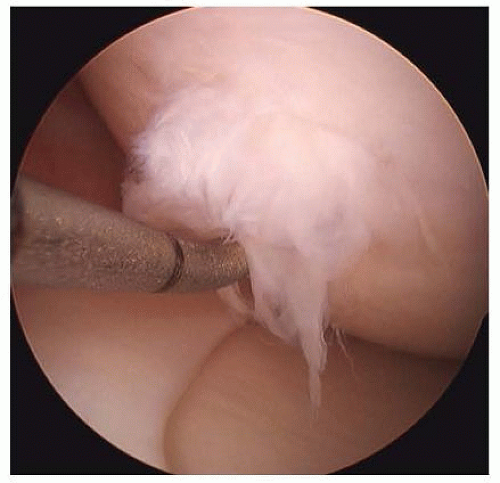

Review of previous imaging studies (typically radiographs and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]), operative reports, and arthroscopic imaging is critical in the evaluation of these patients. In many of these patients, previous surgery and arthroscopic imaging have been performed. Reviewing these studies can provide useful information about the location, depth, and perimeter of the lesion (FIG 1).

The presence of a “kissing lesion” on the opposite articular surface is important, as its presence may alter or preclude certain allograft approaches. Significant osteoarthritis, especially if more diffuse, rather than focal, may be a contraindication to osteochondral allograft use.

Patient factors: Individual patient factors, including patient preferences, alignment of the lower extremities, social resources, work/job demands, and medical comorbidities must be considered when evaluating these patients. Some research has also shown factors such as age older than 30 years and a history of two or more previous surgeries on the joint are associated with poorer outcomes.14

In patients with more advanced osteochondral pathology, the history frequently includes episodes of pain, mechanical symptoms, giving way, and swelling. Both traumatic injuries and patients with OCD may present after months or years of milder symptoms.

These patients may describe the feeling of a loose body within the joint that can occasionally be palpated on the anterior aspect of the knee.

Notable findings include effusion, joint line tenderness, and, in some cases, a mobile free body may be palpated.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The most valuable tools for evaluating osteochondral lesions are high-quality imaging studies, the most basic of which is the weight bearing, plain radiograph of the knee. The authors prefer standing anteroposterior, tunnel, lateral, and Merchant views.

A wealth of information can be gleaned from properly performed radiographs, including the approximate dimensions and location of the lesion and the precedence of diffuse osteoarthritis. Long-standing radiographs are valuable in assessing limb length discrepancy and malalignment.

MRI provides a more detailed look at the condition of the lesion and surrounding cartilage. The MRI may also reveal kissing lesions, in which there is chondral injury on opposing articular surfaces. Careful inspection for malalignment, kissing lesions, or signs of more diffuse cartilage injury is essential, as these factors may change the surgical management of the patient.14 The lesions are less common in younger patients but may increase in frequency in older patients or those with a prolonged history of symptoms.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

OCD

Acute osteochondral fracture

Osteochondral defect

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative management may consist of activity modifications, maintenance of ideal body weight, and low-impact conditioning programs.

Significant mechanical symptoms may not be addressed with this approach.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

With regard to stable OCD lesions, many procedures are designed to promote healing, including subchondral drilling, both antegrade11, 15, 24 and retrograde.26, 28 For unstable lesions, drilling in combination with internal fixation, bone grafting, and other procedures may promote healing. Excision of loose fragments may provide reasonable short-term results, but long-term outcomes are generally poor.17, 18 Although less invasive procedures may improve mechanical symptoms, they may not address the long-term impact of the cartilage or bone defect in a weight-bearing region of the joint.

For patients in whom native cartilage and bone cannot be successfully repaired, or those that have failed previous attempts at repair of native tissue, osteochondral allograft is one option to be considered. Other options to be considered for cartilage loss are outlined in the following text, although some of them may have limitations especially in larger lesions and those with deep subchondral bone loss.

For patients that have focal, full-thickness cartilage defects, several techniques can be used to restore the joint cartilage surface. These techniques include the following:

Marrow stimulation (microfracture)

Osteochondral autograft transfer (OAT)

Cell-based therapies, including autologous cartilage amplification and implantation

Osteochondral allograft implantation

Marrow Stimulation

Marrow stimulation, although relatively simple to perform, has several limitations.

Clot formation secondary to marrow stimulation produces disorganized fibrocartilage characterized by a high concentration of type I collagen rather than type II collagen, which comprises hyaline cartilage.

Fibrocartilage lacks the mechanical integrity and ultrastructural organization of hyaline cartilage and often deteriorates after a few years.9

In addition to poor wear properties, the fibrocartilage formed after marrow stimulation may not restore congruity of the articular surface in cases of OCD, where loss of the subchondral bone and débridement of fibrous tissue results in a deep crater with significant bone loss.

Restoring this subchondral bone loss can present many challenges to the surgeon, both with microfracture, and other cartilage restoration procedures.21

Osteochondral Autograft

OAT may have some advantages for treating OCD, as it can directly address the loss/abnormalities of subchondral bone.

The depth of the osteochondral autograft donor plug can be adjusted to fill the entire defect with viable bone and articular cartilage, which has the capacity to integrate with the adjacent tissue.

There are limitations to the OAT procedure.

Large defects cannot be filled due to donor site morbidity, and there may be problems with articular cartilage incongruence.

The technique precludes filling the entire defect when multiple grafts are used and fibrocartilage forms around the periphery of the grafts.

Wang27 and Horas et al10 reported poor results when osteochondral autografting was used to treat lesions24 larger than 6 cm.

This approach may be reasonable for smaller OCD lesions. In a prospective randomized trial, mosaic osteochondral autograft transplantation demonstrated superior result compared to microfracture for the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents.9

At an average follow-up of 4.2 years, 63% of the microfracture group had good or excellent outcomes, but this group had some deterioration in outcome over 1 to 4 years.

For the mosaic osteochondral autograft transplantation group, 83% had good or excellent outcomes.

There were 41% failures in the microfracture group compared with none in the mosaic osteochondral autograft transplantation group at the final follow-up.

Consequently, in lesions that are small, mosaic osteochondral autograft transplantation is a reasonable procedure that produces outcomes that are superior to microfracture.

As mentioned, one challenge with mosaic osteochondral autograft transplantation is donor site morbidity as well as the differences in cartilage thickness in donor and recipient sites.

Autologous Cartilage Implantation

The use of autologous cartilage implantation (ACI) has been reported for treatment of OCD.23

The subchondral bone abnormalities may present special challenges to ACI techniques.

Due to the loss and/or abnormalities of the subchondral bone base, special ACI approaches have been developed.

Collagen-covered ACI (ACI-C) has been described in a case series, showing positive clinical results at 4 years, but most cases that underwent biopsy revealed fibrocartilage.12

Another multicenter case series using ACI for OCD demonstrated significant improvements, but more than a third of patients required secondary surgical débridement.6

In cases in which the subchondral bone is minimally involved, standard ACI may be considered.

In cases with more significant loss of subchondral bone, staged procedures to supplement regional bone loss may be an option.14

Fresh Osteochondral Allograft

For larger cartilaginous or osteocartilaginous defects, marrow stimulation, osteochondral autografts, and ACI have limitations.

Restoring both bone and cartilage loss is especially challenging in larger lesions. Fresh osteochondral allografts address both the cartilage and bone deficits. In addition, osteochondral allografts produce enough graft material to resurface larger lesions.4

The rationale for fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation is to replace diseased, unsalvageable bone, and cartilage defects in the context of an otherwise healthy joint.

The living chondrocytes from the transplant become a viable part of the recipient’s cartilage matrix, and the transplanted bone is incorporated by the host bone.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree