Abstract

Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is an uncommon localisation of osteoarthritis. Instability of this joint is one of rare aetiologies. It can occur after resection of the pubic symphysis for whatever the reason. The biomechanical consequences on the SIJ are increasing shear forces and vertical restrain. This leads to secondary progressive SIJ osteoarthritis. There is no specific rehabilitation programme for this pathology. Here, we report the case of a patient who presents SIJ osteoarthritis 20 years after surgical resection of the pubic symphysis for osteochondroma. We proposed a rehabilitation programme based on the pelvic biomechanical characteristics. It included specific exercises of muscular strengthening (the transversely oriented abdominal muscles and pelvic floor muscles) and muscular stretching (the psoas major muscle). We obtained an improvement of pain and functional capacity in our patient.

Résumé

L’articulation sacro-iliaque (ASI) est une localisation inhabituelle de l’arthrose. L’instabilité de cette articulation constitue l’une des rares étiologies. Elle peut compliquer la résection de la symphyse pubienne quelle qu’en soit la cause. Dans ce cas, les conséquences biomécaniques au niveau des ASI comportent une augmentation des forces de cisaillement et de tension verticale et vont aboutir progressivement à une arthrose secondaire des ASI. Il n’y a pas de programme de rééducation spécifique à cette pathologie. Nous rapportons le cas d’une patiente présentant une arthrose des ASI 20 ans après résection chirurgicale de la symphyse pubienne pour un ostéochondrome et nous présentons l’apport d’un programme de renforcement musculaire orienté vers la réduction des anomalies biomécaniques.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Although the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is rarely affected by osteoarthritis, SIJ instability can be an aetiology for this condition following resection of the pubic symphysis for whatever reason , including removal of an osteochondroma. Although the latter is a tumour which usually occurs on the metaphyseal surfaces of the leg bones , resection is recommended for pubic sites. The biomechanical consequences of pubic symphysis resection include an increase in shear forces and vertical tension on the SIJ and can trigger secondary, progressive SIJ osteoarthritis . To date, no specific rehabilitation programme for this pathology has been suggested. Here, we report the case of a patient who developed SIJ osteoarthritis 20 years after surgical resection of the pubic symphysis for osteochondroma and for whom we developed a specific strength training programme.

1.2

Case report

The 55-year-old female patient had undergone complete resection of the pubic symphysis in 1986, due to the presence of osteochondroma at the right ischiopubic wedge. A few years later, she developed pain and discomfort in the sacroiliac region. The symptoms were aggravated by climbing and descending stairs and prolonged walking or standing.

On performing a physical examination, we found SIJ pain on mobilization and palpation but otherwise normal orthopaedic and neurologic characteristics (notably of the lumbar spine). Pelvic radiography revealed bilateral SIJ osteoarthritis ( Fig. 1 ). Laboratory tests (including a complete blood count and blood sedimentation rate) were normal. We treated the patient for SIJ osteoarthritis and developed a rehabilitation programme based on analgesic, physical therapy and the strengthening of transversely oriented abdominal muscles (the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique muscles) and pelvic floor muscles (the coccygeus, pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus) in order to reduce vertical SIJ shear forces and thus increase SIJ stability. In view of the biomechanical characteristics of the pelvic , we also suggested stretching exercises for the psoas major muscle. The rehabilitation programme was performed on an outpatient basis and featured a total of 18 sessions (three sessions a week for 6 weeks).

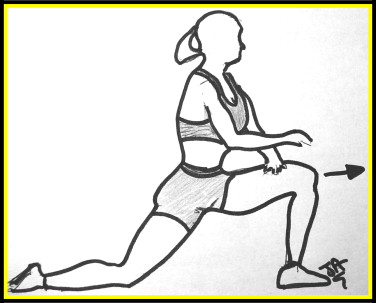

The sessions started with physical analgesic therapy, including transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation electrotherapy and ultrasound treatment. In order to stretch the psoas major muscle, the patient was instructed to carry out an anterior rotation exercise, with three sets of 10 repetitions in each session. The patient moved forward while exerting an extension motion through the hip and creating an anterior rotation on the ilium on that side ( Fig. 2 ).

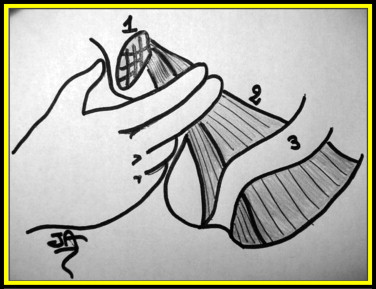

For pelvic floor rehabilitation, we first used a number of diagrams to inform the patient about pelvic floor physiology and anatomy. We initiated an active local muscle strengthening programme during digital vaginal examination in the absence and then presence of counter-resistance. The exercises are simple and easy to perform. In a vaginal examination, the index finger is used to easily evaluate the quality of the pubococcygeus on the right and then on the left whilst the therapist applies pressure (counter-resistance) to the muscle and asks the patient to perform a voluntary contraction ( Fig. 3 ). These exercises were combined with stretching exercises.

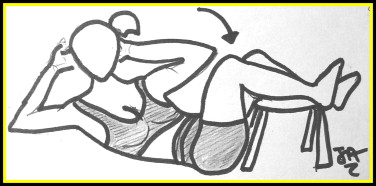

Postural exercises were also used; the training session began in the supine crook position. We taught our patient to perform powerful contraction of the pelvic floor with simultaneous co-contraction of the lower transverse abdominal wall (the transversus abdominis and the transverse fibres of internal oblique) but without any associated breath holding and/or overall bracing of the abdominal wall. These exercises were facilitated by the visual feedback provided by working with a half-full bladder (rising of the hypogastric region, due to pelvic floor contraction).

Once the exercise had been mastered, each contraction had to be maintained for 30 sesconds .

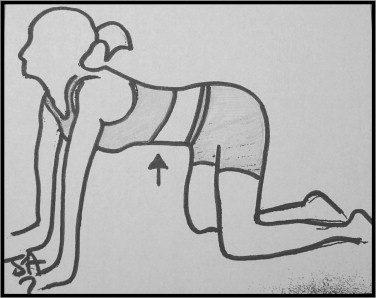

The transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles were also reinforced by isometric exercises, followed by stretching ( Figs. 4–6 ). Internal course isometric contraction was performed for 10 seconds, with 10 seconds of rest (six sets of 10 repetitions per session).

Our patient was instructed to carry out a daily home exercise programme consisting of an extension of the above-described protocol. The goal was to strengthen the lower transverse abdominal wall and stretch the psoas major muscle (two sessions of 10 repetitions daily).

This programme enabled us to improve the patient’s status in terms of pain and functional capacity. No treatments other than class I analgesics were given during the rehabilitation period. Indeed, the score on a pain visual analogue scale (VAS) was reduced by 40 mm (from 60 to 20 mm), the walking perimeter was improved by 200 m (from 300 to 500 m), stair-climbing ability was improved by 17 stairs and patient satisfaction on a VAS was 70 mm. Two months after the end of the protocol, the patient’s satisfaction rating was 59 mm.

1.3

Discussion

Osteoarthritis of the SIJ is rare. Aetiologies for the condition include trauma, infection and other less common disorders of the SIJ, such as crystal arthropathy (gout or pseudogout), osteitis condensans ilii, tumours or tumour-like conditions and, lastly, SIJ instability. The latter condition can occur post-partum or (as in our case) following pubic resection. Loss of the pubic symphysis leads to an increase in the rotational force at the SIJ and, over time, this increased force may result in joint hypermobility and osteoarthritis which may progress slowly over several years. Treatment essentially involves correcting the instability. Most authors seem to agree that arthrodesis of the pubic symphysis is the best solution for avoiding SIJ osteoarthritis . At a later disease stage, arthrodesis of both the pubic symphysis and the SIJ can be envisaged .

Rehabilitation may also be proposed for analgesic and functional purposes. Physical therapy is a commonly used treatment . However, muscle strengthening has rarely been cited in the management of SIJ osteoarthritis, except cases of derangement of the SIJ , in which the rehabilitation protocol included strengthening of the transversally oriented abdominal muscles (the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique muscles) and the pelvic floor .

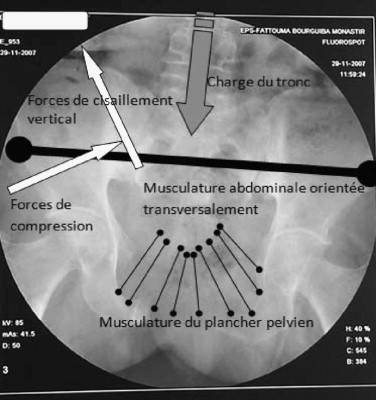

The SIJ surfaces are parallel to the axis of transversally oriented abdominal muscles and are possibly the only joints which experience a large, continuous dislocating load induced by gravity when in the standing position. To prevent joint dislocation by shearing, continuous contraction of the transversally oriented muscles crossing the SIJ is needed to compress these joints (i.e. self-bracing) , despite the fact that the strong, passive, sacroiliac ligament system would be expected to provide sufficient stability . Furthermore, muscles like the rectus abdominis and psoas major muscles (acting longitudinally to the spine) generate forces in parallel with the SIJ’s surfaces and thus produce shear loading . Relaxation of these muscles helps decreasing these shear forces. Although the piriformis is transversally oriented and crosses the SIJ, some authors consider that it does not have a major role in view of the vertical SIJ shear forces induced by this muscle . However, other publications have reported the muscle system’s value in reducing SIJ hypermobility and combating progressive osteoarthritis . In view of this literature debate, we decided not to include the piriformis in our rehabilitation programme.

The pelvic floor muscles (the coccygeus, pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus) contribute to stabilization of the sacrum by increasing the compression forces exerted by the two iliac bones, by analogy with a classical stone arc . In the pelvis, the pelvic floor muscles may exert compression force to help the coxal bones support the sacrum, whereas shear forces between the sacrum and the coxal bones are minimized . Furthermore, simultaneous contraction of the transversally oriented abdominal muscles and the pelvic floor muscles helps decrease vertical shear forces and increase SIJ compression and stability ( Fig. 7 ).

In light of these observations, we developed a SIJ stabilization training-programme with two main objectives:

- •

to reduce vertical shear forces by stretching the psoas major;

- •

to increase the stability provided by compressive forces by strengthening the transversus abdominis, the internal abdominal oblique muscle and the pelvic floor muscles.

Particular features of our case included the advanced state of the SIJ osteoarthritis and the high degree of instability following the pubic symphysis resection.

In the literature, the McKenzie Method of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT) has been used in cases of derangement of the SIJ, with significant improvements in symptoms . A combination of pelvic floor strengthening and simultaneous co-contraction of the lower transverse abdominal wall has been used to prove the ability of a motor learning intervention to change aberrant pelvic floor and diaphragm kinematics and respiratory patterns observed in subjects with SIJ pain during the active straight leg raise, with resulting improvements in pain relief and functional ability . In fact, our treatment combined exercises from both approaches. Lastly, many authors have insisted on the importance of self-treatment and home exercises .

1.4

Conclusion

In a case of SIJ osteoarthritis complicating pubic symphysis resection, we developed a rehabilitation programme based on reinforcement of the lower transverse abdominal wall and pelvic floor muscles and stretching of the psoas major muscle, with a view to effective relief of pain and functional impairments. This contribution must now be confirmed in a larger population.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’arthrose siège rarement au niveau de l’articulation sacro-iliaque (ASI). L’instabilité de cette articulation en est une étiologie inhabituelle. Elle peut compliquer la résection de la symphyse pubienne quelle qu’en soit la cause . Il s’agit rarement d’un ostéochondrome qui est une tumeur qui survient généralement sur les surfaces « métaphysaires » des os longs et très rarement au niveau pubien, et qui nécessite un traitement par résection . Dans ce cas, les conséquences biomécaniques au niveau de l’ASI consistent en une augmentation des forces de cisaillement et « de tension verticale ». Cela conduit à l’installation d’une arthrose secondaire progressive de l’ASI . Il n’existe pas de programme de rééducation spécifique à cette pathologie. Nous rapportons ici le cas d’une patiente qui présente une arthrose de l’ASI compliquant une résection chirurgicale de la symphyse pubienne pour le traitement d’un ostéochondrome. Nous lui avons proposé un programme spécifique de renforcement musculaire.

2.2

Cas clinique

Il s’agit d’une femme de 55 ans ayant une résection complète de la symphyse pubienne. Ce traitement a été effectué en 1986 pour un ostéochondrome de la branche ischiopubienne droite. Quelques années plus tard, elle a développé des douleurs de l’ASI de type mécanique. Les symptômes sont aggravés par la longue marche, la montée et la descente des escaliers et la station debout prolongée. La prise d’anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens et d’analgésiques de classe I et II n’a amélioré la patiente que partiellement et transitoirement. Le retentissement fonctionnel était important. L’examen physique trouve des douleurs à la palpation et lors des manœuvres sollicitant les ASI. Le reste de l’examen physique y compris du rachis lombaire était sans particularité. La radiographie du bassin a montré une arthrose bilatérale de l’ASI ( Fig. 1 ). Un bilan biologique comportant une numération formule sanguine et une « vitesse de sédimentation » était normal. Nous avons pris en charge la patiente pour l’arthrose des ASI. Nous avons ainsi proposé un programme de rééducation basé sur la physiothérapie antalgique et le renforcement de la musculature abdominale orientée transversalement ( transversus abdominis et obliques internes) et les muscles du plancher pelvien ( coccygeus , pubococcygeus et iliococcygeus ) afin de réduire les forces de cisaillement vertical au niveau des ASI et d’augmenter ainsi leur stabilité. Nous avons aussi proposé des exercices d’étirement du muscle psoas major . Cette approche a été guidée par les caractéristiques biomécaniques pelvienne . La rééducation s’est déroulée en ambulatoire et a comporté 18 séances (trois par semaine) pendant six semaines.