Osteoarthritis of the Hip

Kristofer J. Jones

Charles L. Nelson

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

OA is the most prevalent form of arthritis leading to eventual degenerative joint destruction, and it is a leading cause of impaired mobility in older patients. Arthritic disease of the hip can significantly hinder lifestyle choices in the active aging population, thereby significantly affecting an individual’s quality of life. Ultimately, the gradual development of functional limitations can lead to significant disability. The societal burden of this condition, in terms of both personal suffering and utilization of health resources, is on the rise with the increasing prevalence of obesity and the increased life expectancy of the general population.1

Patients with OA of the hip typically present with complaints of insidious pain in the groin or inguinal region and, on occasion, may report pain on the side of the buttock or upper thigh. The joint pain of OA is typically exacerbated by varied amounts of weight-bearing activities and is usually relieved with cessation of physical activity. In more advanced cases, it is not uncommon for patients to complain of pain at rest or even at night. It is important to note that while symptoms of pain at night can represent severe symptomatic disease, it can also point to causes other than OA, such as inflammatory arthritis, tumors, infection, or crystalline arthropathy. For OA of the hip, activities such as walking long distances or even putting on shoes and socks can produce significant pain. In general, the hip pain is more pronounced in the morning as patients complain of “stiffness” when they wake up. This morning stiffness tends to last no more than 30 minutes and gradually resolves as the patient begins to ambulate and mobilize the involved joint. On occasion, patients may complain of associated mechanical symptoms (“locking, catching, clicking”).

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Physical examination of the patient should begin with an initial assessment of body weight and height to establish the patient’s body mass index, as obesity is a significant contributing factor to osteoarthritic disease. The patient should then be adequately undressed for focused inspection of the hips and pelvis. A comprehensive examination should be performed with the patient upright (standing) and supine on the examination table.

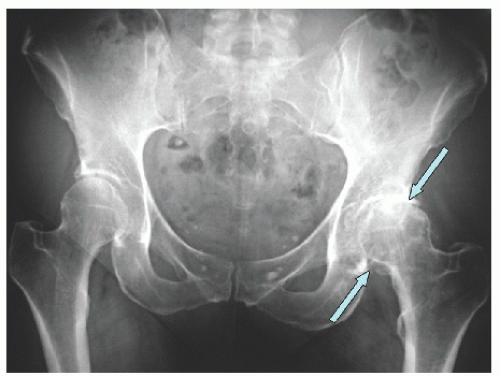

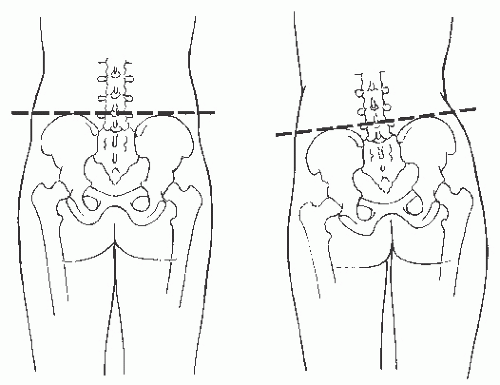

With the patient in the upright position, it is important to inspect the pelvis for any signs of obliquity by palpating the iliac crests, as this clinical sign may suggest the presence of a significant leg length discrepancy or spinal deformity (Fig. 11-1). Clinical leg length discrepancy is not uncommon in patients with OA, as the loss of joint space at the hip can result in significant shortening of the involved extremity. A Trendelenburg test can be performed by having the patient stand on the affected extremity and lift the contralateral leg with the hip and

knee flexed approximately 90 degrees. Patients with deficient abductor muscles or pain on contraction of these muscles secondary to arthritis demonstrate an impairment of this normal mechanism. Consequently, these patients will allow the pelvis to drop contralateral to the stance phase side or may even shift their center of gravity over the stance phase in order to reduce the muscular demand of the involved leg. Finally, gait should be assessed to determine if the patient has signs of an antalgic or Trendelenburg gait. An antalgic gait is characterized by a short stance phase and stride length on the affected extremity secondary to pain. A Trendelenburg gait refers to a patient’s tendency to lean over the affected hip during the stance phase in an attempt to shift the center of gravity toward the arthritic hip and compensate for weak abductor musculature.

knee flexed approximately 90 degrees. Patients with deficient abductor muscles or pain on contraction of these muscles secondary to arthritis demonstrate an impairment of this normal mechanism. Consequently, these patients will allow the pelvis to drop contralateral to the stance phase side or may even shift their center of gravity over the stance phase in order to reduce the muscular demand of the involved leg. Finally, gait should be assessed to determine if the patient has signs of an antalgic or Trendelenburg gait. An antalgic gait is characterized by a short stance phase and stride length on the affected extremity secondary to pain. A Trendelenburg gait refers to a patient’s tendency to lean over the affected hip during the stance phase in an attempt to shift the center of gravity toward the arthritic hip and compensate for weak abductor musculature.

FIGURE 11-1. Pelvic obliquity may be due to a significant leg length difference or spinal deformity. (MediClip image copyright (c) 2003 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved.) |

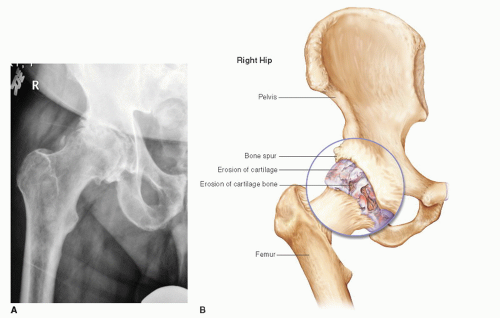

Supine examination should begin with observation of the resting position of the affected extremity. In the presence of hip OA, patients tend to hold the hip in a position of slight flexion, abduction, and external rotation to decrease intra-articular pressure, resulting in diminished hip pain. Examination of hip range of motion should include accurate measurement of both passive and active movement. Patients typically display limitations in passive external and internal rotation of the hip secondary to pain and/or mechanical abnormalities (i.e., osteophyte formation). Abduction and internal rotation are typically more restricted than adduction and external rotation. Occasionally, joint crepitus can be detected with passive range of motion. This “crackling” sensation is due to the irregularity of opposing cartilage surfaces and is a frequent sign of OA. One helpful test to detect intra-articular hip pathology includes the Stinchfield test. In the supine position, the patient is asked to elevate the affected extremity to 20 to 30 degrees with the leg in full extension. A positive test is characterized by reproduction of significant hip or groin pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree