Osteoarthritis: Foot/Ankle Joints

Steven M. Ralkin

Ankle Arthritis

Osteoarthritis can practically affect any joint in the foot and ankle and in any combination of joints. The more common locations of osteoarthritis include the following:

Ankle (tibiotalar joint)

Three joints of the hindfoot: the subtalar or talocalcaneal joint, the talonavicular joint, the calcaneocuboid joint

Midfoot (tarsometatarsal [TMT] joints)

Great toe (first metatarsophalangeal [MTP] joint)

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Ankle arthritis presents with a history of progressive pain, swelling, and diminishing range of motion of the ankle or tibiotalar joint, predominantly with ambulation. The most common underlying factor is posttraumatic that can follow a remote ankle or tibia fracture (which may have been treated surgically or with a cast) or recurrent ankle sprains (ankle instability). Inflammatory arthritis (such as secondary to rheumatoid arthritis), Charcot neuroarthropathic changes, and postinfective arthritis are additionally seen, but true primary arthritis is less frequently seen than it is in the hip or knee area.

CLINICAL POINTS

Any joint in the foot or ankle may be involved.

Symptoms may vary, depending on which joint is affected.

Pain and swelling are common.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients should be examined both sitting and while walking. Gait evaluation commonly reveals an antalgic gait pattern, where the patient will spend more time with the normal foot planted (stance phase), while hurrying the step while the effected limb is planted. Additionally, the patient may walk with the affected limb externally rotated to compensate for the diminished range of motion in the arthritic ankle.

On inspection, there is usually asymmetry with swelling of the affected ankle. Careful assessment for prior scars suggestive of previous trauma or surgery should be undertaken and the causes documented. The ankle may be tender to palpation, with this being exacerbated by ankle motion. Range of motion is typically reduced as compared with that found in the contralateral ankle, with particular reduction in dorsiflexion and plantar flexion on the ankle. Muscle strength of both lower extremities reveals no atrophy or abnormal movements.

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

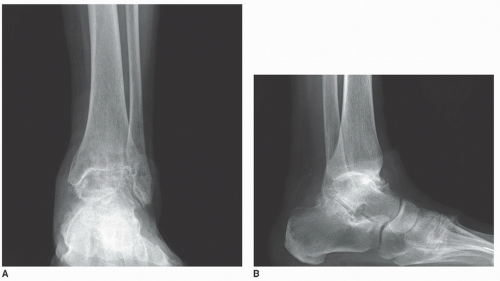

Weight-bearing x-ray views of the ankle are obtained (Fig. 32-1). On the x-rays, the clinician should look for alignment, joint space narrowing and symmetry, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte formation, and degenerative cyst formation.

An magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination may be useful in milder arthritic cases when x-rays are normal,

or in cases of localized arthritis where joint space narrowing may not be evident on standard x-rays. These are also useful in suspected infection or periarticular tendenopathies.

or in cases of localized arthritis where joint space narrowing may not be evident on standard x-rays. These are also useful in suspected infection or periarticular tendenopathies.

A computed tomography (CT) scan may be useful in posttraumatic cases if a nonunion of the fracture or bony defects are suspected.

TREATMENT AND CLINICAL COURSE

Treatment will depend on the nature and severity of the ankle arthritis, both subjectively to the patient and objectively by studies. Patients with ankle arthritis can be managed conservatively with NSAIDs, weight loss, and activity modification. The addition of a rocker bottom to the sole of the shoe will help compensate for loss of motion in the ankle joint and aid ambulation. Narcotics should be avoided whenever possible due to high rates of dependence and tolerance to these medications.

More advanced cases may require joint immobilization to restrict range of motion and unload the ankle joint. This may be achieved with over-the-counter braces in milder cases, but more advanced arthritis will require a custom-molded ankle-foot orthosis (MAFO), such as an Arizona brace or MAFO. Intraarticular corticosteroid-anesthetic injections can be attempted, but no more frequently than once every 4 months. Hyaluronic acid substitutes, such as Synvisc or Hyalgan, have not been U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved for use in the ankle, as the clinical data have not shown the efficacy of this treatment. Supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate have been studied in knee arthritis, yielding conflicting results.

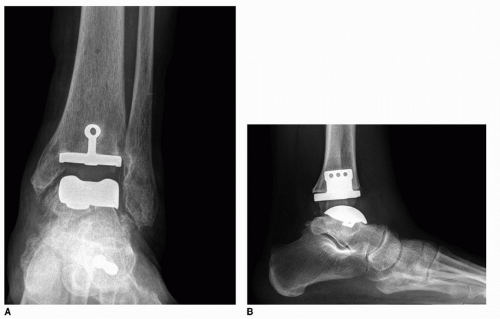

Once patients have end-stage osteoarthritis of the ankle, surgery may be indicated. There is little evidence to support arthroscopic debridement of an arthritic ankle, except in localized forms such as osteochondral defects or anterior impingement. Definitive treatment for an arthritic ankle includes either an ankle arthrodesis or fusion, or a total ankle arthroplasty (Fig. 32-2).1

Important Points in Treatment

Treatment depends on the nature and severity of the arthritis.

Clearly, the early use of nonoperative treatment consisting of weight reduction, activity modification, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be helpful.

In severe cases, surgical treatment may be necessary.

Although patients may wax and wane in their response to different conservative measures for ankle arthritis, over an extended period of time, patients will continue to worsen. It is important for the patient to realize that the arthritis is not curable.

Subtalar Arthritis

A 31-year-old woman presents with a history of increasing pain and discomfort of the right ankle. This is particularly bothersome on uneven surfaces. She has a history of a prior ankle sprains to that limb.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|