Abstract

Specific soluble biomarkers can be powerful tools for the diagnosis, prognosis and personalized management of osteoarthritis (OA). Biomarkers are potential indicators of the effect of a drug on cartilage metabolism and provide crucial information about the mechanisms of drug action. In this review, we address key questions concerning the use of biomarkers in OA management: Why do we need soluble biomarkers? What are the most widely investigated biomarkers derived from cartilage extracellular matrix? What are the most common pitfalls in interpreting soluble biomarker measurements? What are the perspectives and future research directions in this field? We review current evidence to propose that cartilage-derived soluble biomarkers are complementary “drug development tools” that can be applied during drug development from preclinical research to clinical evaluation. In the future, such biomarkers could be surrogate markers of clinical and/or imaging outcomes. Successful standardization and implementation of automated biomarker assays will facilitate their use in companion diagnostics in the context of personalized medicine for enhanced management of OA.

1

Introduction

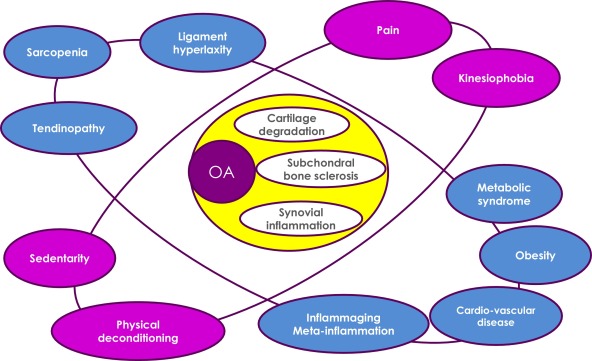

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the major causes of pain and disability in the adult population. OA is now considered a severe joint disease affecting all articular tissues (i.e., cartilage, synovial membrane, meniscus and ligaments) and also periarticular tissues including tendons, adipose tissue and muscles. These joint tissues undergo metabolic, structural and functional alterations that contribute to the initiation and increased chronicity of pain and synovitis, activating pro-inflammatory pathways of innate immunity, facilitating disease progression and leading to patient disability. OA is a risk factor for some other age-related co-morbidities such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases . Therefore, OA must be better managed to prevent these co-morbidities.

Pain is a key determinant of kinesiophobia in OA patients; it is responsible for physical deconditioning and a sedentary lifestyle, which is probably a decisive factor in the association of OA and metabolic syndrome, obesity and cardiovascular disorders . Low-grade chronic systemic inflammation is the link between articular and periarticular tissues via pro-inflammatory mediators. This low-grade systemic inflammation may result from physiological aging (inflammaging) or metabolic disorders (meta-inflammation) ( Fig. 1 ).

The challenge for the next decade will be to find better remedies and management strategies for OA and to identify tools that can help in diagnosis and monitoring disease progression as well as assessing the efficacy of new therapeutic interventions. These tools need to be accurate for monitoring the structural progression of the disease and sensitive enough to identify early events at the molecular level and objectively assess the efficacy of novel or preexisting therapeutic modalities. Soluble biomarkers are among these tools. This review addresses the following key questions concerning the use of biomarkers in OA management.

2

How to define and classify OA biomarkers?

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Biomarkers Definitions Working Group defined a biomarker as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” . Existing biomarkers can be categorized by the OA process targeted, as markers of cartilage degradation/synthesis, bone remodeling, or synovitis. They can also be classified as “dry” or “wet” biomarkers. “Dry” biomarkers may include imaging features, visual analog scales or questionnaires and “wet” biomarkers may include proteins, protein fragments, metabolites or microRNAs. The BIPEDS system classifies the major types of biomarkers according to their clinical background into 6 categories corresponding to burden of disease, investigational, prognostic, efficacy of intervention, diagnostic and safety . The adoption and use of this classification system has been encouraged to communicate advances within a common framework and so that OA biochemical marker research is more transparent and efficient, offering suggestions on optimal study design and the development of analytical methods for use in OA-focused investigations. In 2011, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International/Food and Drug Administration (OARSI/FDA) Biomarkers Working Group classified biomarkers into 4 categories (exploration, demonstration, characterization and surrogacy levels) by their level of qualification for drug development . More recently, the OARSI RCT working group published guidelines for soluble biomarker assessment in OA clinical trials . This document summarizes the use of biomarkers at 5 stages, including preclinical development and phase I to IV trials.

2

How to define and classify OA biomarkers?

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Biomarkers Definitions Working Group defined a biomarker as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” . Existing biomarkers can be categorized by the OA process targeted, as markers of cartilage degradation/synthesis, bone remodeling, or synovitis. They can also be classified as “dry” or “wet” biomarkers. “Dry” biomarkers may include imaging features, visual analog scales or questionnaires and “wet” biomarkers may include proteins, protein fragments, metabolites or microRNAs. The BIPEDS system classifies the major types of biomarkers according to their clinical background into 6 categories corresponding to burden of disease, investigational, prognostic, efficacy of intervention, diagnostic and safety . The adoption and use of this classification system has been encouraged to communicate advances within a common framework and so that OA biochemical marker research is more transparent and efficient, offering suggestions on optimal study design and the development of analytical methods for use in OA-focused investigations. In 2011, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International/Food and Drug Administration (OARSI/FDA) Biomarkers Working Group classified biomarkers into 4 categories (exploration, demonstration, characterization and surrogacy levels) by their level of qualification for drug development . More recently, the OARSI RCT working group published guidelines for soluble biomarker assessment in OA clinical trials . This document summarizes the use of biomarkers at 5 stages, including preclinical development and phase I to IV trials.

3

Why do we need soluble biomarkers in OA?

The management of OA often begins too late during the course of the disease. It is generally initiated after the patient complaints about joint pain and loss of function, which is confirmed by the presence of radiographic changes . Unfortunately, by the time the disease is diagnosed radiographically, joint tissue degeneration is already well established and in most cases irreversible. Clinical OA is now considered to be preceded by a “silent” pre-radiographic phase during which extensive metabolic changes occur in joint tissues, without any pain. One challenge is the detection of these early metabolic changes that are early indicators of abnormal joint changes before the occurrence of structural changes.

OA is a heterogeneous syndrome with different clinical phenotypes defined by risk factors, progression profiles, co-morbidities, signs and symptoms. Although one goal is to have clearly defined and demarcated OA phenotypes, the classification and identification of phenotypes of OA is difficult in clinical studies or in clinical practice because of all these factors. Thus, we need a better subgrouping of OA, especially when several processes may overlap and various tissues are dominant during different phases of the disease. In real life, different OA phenotypes likely overlap significantly and thus are difficult to be separated into distinct clusters. However, establishing better-defined biological profiles specific to each phenotype may help in clustering the phenotypes.

Another key concern in OA management is the absence of effective treatment or cure. We lack standard treatments that allow for objective assessment of the sensitivity of a biomarker to a particular intervention and innovative treatments that efficiently address symptoms and disease progression. The reasons for the lack of effective treatments are the lengthy follow-ups and large sample sizes required for phases II and III clinical trials. We need sensitive and reproducible variables to accelerate drug development and reduce costs and attrition in the pharmaceutical pipelines. Soluble biomarkers could be considered “drug development tools” accompanying drugs from screening to post-marketing phases .

Many scientists and clinicians believe that soluble biomarkers could be helpful tools for addressing all these concerns. However, the development of a biomarker is a lengthy process requiring robust and reproducible assays that pass independent validation tests as well as the clinical characterization of the biomarker in large cohorts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree