Treatment of chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) with high-dose opioids (HDOs) has burgeoned over the past 2 decades in the United States. Characteristic domains and features of the failed CNCP management patient using long-term HDOs are described herein as the/an opioid syndrome (Schreiber AL, personal communication. 2013). Reversing or even modulating HDO use in patients with CNCP requires a paradigm shift on the part of physician, patient, and the societal “quick fix” medical culture. This review offers measures, agents, and strategies to consider in management of this pervasive, erosive medical and societal challenge.

Key points

- •

There is an alarming incidence of reported chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) in the United States despite a significant expansion of opioid therapy over the past 2 decades.

- •

Failed opioid therapy in CNCP is characterized by high-dose use without perceived improvement in function, quality of life, or pain reduction.

- •

Chronic opioid therapy (COT) produces dependence behaviors in medically compromised CNCP similar to recreational opioid substance use disorders.

- •

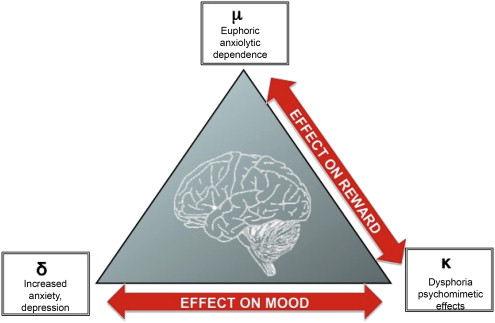

Buprenorphine has partial agonist endorphin effect on mu receptors and antagonist effects on dynorphin-biased kappa receptors when used in the treatment of opioid dependence (OD) maintenance in CNCP.

- •

Comprehensive CNCP management may require balanced low-dose opioids in a continuum of a biopsychosocial care environment oriented toward engaging patients in self-directed care of a chronic disease.

Opioid syndrome is a descriptive term for failed opioid therapy in CNCP, when treatment becomes a problem more than a solution.

Demographics

Progressive incorporation of high-dose opioids (HDOs) (>100 mg/d of morphine equivalents) evolving in the United States over the past 20 years for the treatment of CNCP have failed to stem the rising tide of patients identifying themselves as having chronic pain. CNCP is deemed a major disease demographic by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) affecting more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined. The CDC survey identifies up to 30% of the population or over 100 million people in the United States with CNCP. Physicians who declare an interest in addressing this complex problem are saddled with a staggering number of people who have failed to achieve satisfactory subjective pain relief with the use of even staggering high doses of opioids. To many practitioners, this dichotomous, failed, relationship between opioids and chronic pain has become more of a problem than an efficient solution. Fortunately, the CDC report also deems chronic pain as one of the 9 potentially better treatable conditions deserving additional research attention. Enhancing CNCP treatment will require a significant shift in our medical effort to harness current and future opioid and nonopioid medications and nonmedical interventions. Recognition of chronic pain as a physiologic impairment of the brain, the central nervous system (CNS), the neuromusculoskeletal system and psychosocial environment will be a critical factor in this novel approach to address the epidemic impact of CNCP. The “quick fix” model of opioid treatment of CNCP needs a conceptual shift as well by practitioners and consumers in our current medical culture. This article serves to (1) identify the source of some of the many potential pitfalls of HDO therapy, (2) help the pain practitioner construct a motivational interview to foster patients’ self-introspection regarding the sustainability and value of HDOs, and (3) provide perspective on opioid pharmacology to begin the process of restructuring treatment options.

Demographics

Progressive incorporation of high-dose opioids (HDOs) (>100 mg/d of morphine equivalents) evolving in the United States over the past 20 years for the treatment of CNCP have failed to stem the rising tide of patients identifying themselves as having chronic pain. CNCP is deemed a major disease demographic by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) affecting more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined. The CDC survey identifies up to 30% of the population or over 100 million people in the United States with CNCP. Physicians who declare an interest in addressing this complex problem are saddled with a staggering number of people who have failed to achieve satisfactory subjective pain relief with the use of even staggering high doses of opioids. To many practitioners, this dichotomous, failed, relationship between opioids and chronic pain has become more of a problem than an efficient solution. Fortunately, the CDC report also deems chronic pain as one of the 9 potentially better treatable conditions deserving additional research attention. Enhancing CNCP treatment will require a significant shift in our medical effort to harness current and future opioid and nonopioid medications and nonmedical interventions. Recognition of chronic pain as a physiologic impairment of the brain, the central nervous system (CNS), the neuromusculoskeletal system and psychosocial environment will be a critical factor in this novel approach to address the epidemic impact of CNCP. The “quick fix” model of opioid treatment of CNCP needs a conceptual shift as well by practitioners and consumers in our current medical culture. This article serves to (1) identify the source of some of the many potential pitfalls of HDO therapy, (2) help the pain practitioner construct a motivational interview to foster patients’ self-introspection regarding the sustainability and value of HDOs, and (3) provide perspective on opioid pharmacology to begin the process of restructuring treatment options.

Opioid syndrome concept

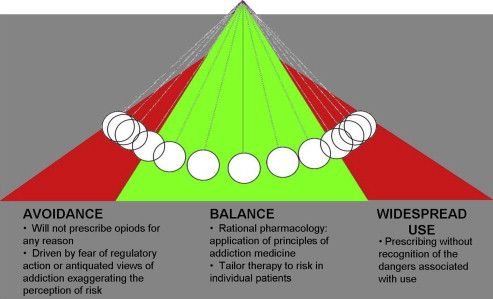

Opioid syndrome (OS) may be constructed as a constellation of signs of a failed therapeutic medical intervention falling into identifiable clinical domains and presentation patterns ( Table 1 ). Patients taking medically prescribed opioids for more than 3 months are likely to be on these medications for more than 2 years, or longer when on high doses, often exhibiting aberrant behaviors. Opioids, when administered long term, are associated with expected (on part of the treating physician) or desired (on part of the patient) and unwanted effects ( Table 2 ). Long-term use of HDOs may also be associated with the development of abnormal sensitivity to pain or hyperalgesia. Ballyntyne in her review of opioid therapy for CNCP states that opioid dose escalation may be the result of “pharmacologic opioid tolerance, opioid-induced abnormal pain sensitivity, or disease progression”. Data regarding the long-term morbidity and mortality of long-term opioids prescribed for CNCP are primarily limited to hard endpoints, including death from use or abuse. The CONSORT study (Consortium to Study Opioid Risks and Trends) studied opioid use for CNCP from 1997 to 2005 and included adult members of 2 health plans serving over 1% of the US population. Patients prescribed 100 mg/d or more had an 8.9-fold (confidence interval 4.0–19.7) increase over the 0.2% rate for 1–20 mg Morphine Equivalent Dose/day (MED/d) in overdose risk (1.8% annual overdose rate). Functional data were not reported in this study. Despite a paucity of credible long-term analysis of COT, the medical management of chronic painful conditions has trended to the right in the pendulum swing from underprescribing to overprescribing ( Fig. 1 ). From 1999 to 2010, the sales of opioid analgesics increased 4-fold. During this same period, the average amount of analgesic consumed for pain relief has increased disproportionately: in 1997, the average MED/d consumed was 96 mg, and this increased to more than 710 MED/d in 2010. Aggressive use of opioid management for CNCP has been fueled by many factors. Well-intentioned primary care practitioners (PCPs) and a growing cadre of pain specialists, orthopedic surgeons, and dentists, fueled by pharmaceutical marketing may represent an unanticipated medical source of OS. Coupled with illegal procurement through friends, family, and felons, the flames of a societal epidemic of opioid abuse have been ignited. This phenomenon has recently been acknowledged by Portnoy who advanced the concepts of COT in the 1990s for CNCP. Some of the most outspoken proponents of COT for CNCP in the 1990s and early 2000s have readdressed the issue and concluded that there is a lot of reeducation required for the phalanx of physicians who have adopted aggressive opioid prescribing ( Box 1 ).

| Domain | Typical Presentations | Contribution/Frequency | Additional Common Presentations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic symptoms | Diffuse myalgias Arthralgias Neuralgias | Limited specificity ++++ | Sleep-wake activity cycle disorders |

| Physical signs | Impairments in mobility/physical capacity | Perceived greater than demonstrated Subjective > objective +++ | Kinesiophobic dyskinetic motions (eg, lumbopelvic, scapulohumeral dyskinesias) Deconditioning |

| Imaging | Incidental inconsequential/or mild-to-moderate degeneration | Anatomic degeneration but not specific to individual symptoms/+++ | Limited insight as to the value of imaging in dx and tx |

| Psychological issues | Depressed/anxious/PTSD/amotivational/somatization/preoccupation with minutia | Lacking and/or rejection of mental health support/+++ | Prone to catastrophizing Pathologizing benign medical elements; loss of locus of control |

| Medical comorbidities | Multiple treaters, treatments | List of providers Polypharmacy/+++ | Diabetic neuropathy + peripheral entrapments, CRPS + contracture |

| SA concerns | Prior or current SA including tobacco | Denial of SA or neglect of SA services/+++ | Tobacco and/or alcohol abuse with+ family history of the same |

| Social patterns | Dysfunctional or limited social interactions/nonsupported/impairment enabled | Critical loss of self-esteem or codependency on disability status/++ | Codependent/enabled by secondary gain (compensation) or anger issues (seeking retribution) |

| Functional performance/pain (VAS) levels | Unchanged by opioid use, disproportionate to examination and diagnostic data | Critical to justification of continued use Requires temporal reassessment/+++ | Dependent on exogenous substance to perform tasks/limited insight as relationship of medication to function |

| Vocational directions | Employed with restrictions/unemployed limited transferable skills On compensation—work or disability related | Societal implications reproductivity/costs of downtime/++ | Unable to actuate lateral or horizontal change in vocational directions |

| Therapeutic Positive Values | Positive Symptoms | Negative/Adverse Symptoms | Additional Negative Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesia | Pain relief | Dependence | Cognitive dysfunction |

| Addiction behavior | Psychomotor slowing | ||

| Anxiolytic | Sedative | Euphoria | Mood changes |

| Tolerance | Hallucinations | ||

| Pruritis | Delirium | ||

| Antidyspnea | Used in acute myocardial and trauma conditions | Respiratory depression | Sleep disturbance Myoclonus Hyperhidrosis |

| Antigastrointestinal hypermotility | Decreased transit time in diarrheal disorders | Nausea | Dry mouth |

| Vomiting/constipation/obstruction | Periodontal disease Loss of Teeth | ||

| Antisalivation | Used to dry excessive oral salivary activity | Endocrine disorders Immune system dysfunction | Hyperalgesia Allodynia Hypesthesia |

We overshot our mark, all well-intended, I believe… we certainly have a lot of reverse education that needs to occur.

Opioid dependence in the medically compromised CNCP population

The phenomena of OD and tolerance have been aptly defined and redefined in the pain and psychiatric literature. Controversy ensues when discussing opioid use disorders in the medically involved CNCP population when bias is perceived in crafting these definitions referring primarily to the recreational user. Dependence is a physiologic response, resulting in adaptation, whereby long-term use of opioids results in well-recognized and enumerated withdrawal symptoms (ie, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale) on discontinuation of use (conceived as recreational). Tolerance falls into the lines of either adaptive or associative tolerance. Adaptive tolerance refers to physiologic changes in receptor and transmitter makeup (recreational or CNCP related). Associative tolerance relates to environmental and social cues. Associative tolerance is the common explanation for overdose in which experienced recreational abusers died when using the same drug outside of their familiar environment. Classical definitions of OD and tolerance do not encompass what pain clinicians frequently encounter. The HDO user exhibits associative tolerance and OD in the context of an unrelenting perception of physical and/or social stress while being prescribed opioids for CNCP ( Table 3 ). Dopaminergic reward behavior is being satiated without an improvement in the anatomic (ie, spinal or muscle pain) pathology. A vicious cycle effect is put into play with no expectation that the opioid will fix any problem other than the dependence it creates, which may represent both an adaptive and an analogous associative dependence.

| Opioid Dependent—Recreational | Opioid Dependent—Chronic Pain |

|---|---|

| Compulsion | Unresolved pain focus |

| Difficulty controlling use | Frequent use of breakthrough pain medications |

| Withdrawal symptoms | Withdrawal symptoms interpreted as return of primary pain |

| Tolerance | Tolerant to high-potency opioid medications/and or hyperalgesic |

| Neglect of alternative pleasures | Altered social/occupational interactions |

| Persist in use despite known harm | Altered insight and judgment as to benefit/harm of medications |

Chronic pain is a disease state with an aberrant sensory (both peripheral and central) and psychologically modulated perception along with physiologic changes subject to adaptation and association. Treatment of CNCP with opioids that cross boundaries of adaptation, dependence, and tolerance with demonstrated physiologic responses in the glial cells and dorsal horn of the spinal cord cannot be held to definitions designed for the recreational user seeking a transient altered perception or engrossed in self-destructive behaviors. Therefore, in the context of CNCP compared to recreational use, dependence and addiction require redefinition. The original intention of these terms did not account for or encompass the CNCP user. Application of the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (DSM-IV) definition of OD outside of the context of recreational use is not sensitive to the unique adaptive pharmacology of opioids. There is significant potential for false-negative interpretation in identifying OD, tolerance, and abuse, when using only recreationally derived inclusion parameters for patients with CNCP. Substance abuse disorders are complex behaviors with multiple neurotransmitter-mediated, genetically programmed behaviors and environmental triggers requiring an evolving fine-tuning of our current system of definition (eg, evolution of DSM-I through V).

Clinician’s role in the evolution of HDO therapy and the OS

Clinicians are expected to identify and curtail malicious use of opioids by means of Opioid Risk Tool (ORT), ( Table 4 ) urine drug screening, pill counts, monitoring of aberrant behaviors, and in some states, electronic prescription drug monitoring. The policing aspect of care consumes significant resources for clinicians in time, paperwork, and staffing that may be in conflict with the additional medical care needs of the outpatient clinic population. If office staff is overwhelmed with the logistics of prescribing, evaluating, rewriting, and monitoring opioid therapy, the practitioner is at great risk of medication and compliance errors that jeopardize patient and public safety as well as licensure requirements. Pressurized office schedules and inadequate staffing conditions often result in escalation of opioids in CNCP because this is the path of least resistance when confronting challenging subjective perceptions of flaring pain symptoms. Decisions to increase opioid dose are filtered into a clinician’s matrix of knowledge regarding a sometimes nebulous diagnosis, as is often the case in chronic pain. Frequently, there is no observed active shift or objective anatomic derangement that fully accounts for the fluctuation of pain perception of the HDO patient’s exacerbation (ie, radiculopathy, arthritic or myofascial pain). Rather, pain can be potentiated and maintained by certain physiologic challenges (hyperalgesia), psychological challenges (ie, depression, stress, manic behavior), and/or functional overuse. Upward dose titration is made against a subjective more than objective analysis of these conditions. The clinician must also consider factors other than the patient, such as the intrinsic properties of the opioid being selected. The unique properties of opioid receptors ( Fig. 2 ), cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme systems, as well as “drug likability” remain critical factors in dosing. Personalities of both opioid users and physician prescribers themselves in a busy outpatient office abound in various forms of calculating manipulation, neediness, and likability as well. This scheme plays out everyday in a pain management practice, factoring into the complex biopsychosocial environment that has contributed to an abundance of opioid prescriptions in the United States.

| Tool | Format | Administration/Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid Risk Tool | A 5-item self-report measure to assist in predicting the probability of aberrant drug-related behaviors when prescribed opioids for pain | Each risk factor is composed of one or more items, with the entire measure consisting of 10 items; items are scores with a possible total score range from 0 to 26 |

| SOAPP | A 24-item self-report questionnaire to assist in determining potential risk of abuse when prescribing opioids for pain | SOAPP items were summed to address a range of variables that may increase risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior, including family history of substance use, mood swings, legal problems, etc. Scored on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often); total scores can range from 0 to 56 |

| DIRE | Clinician-rated measure designed to predict efficacy of analgesia and patient compliance with long-term opioid analgesic treatment | Four subcategories, including psychological, chemical health, reliability, and social support Scores on each category range from 1 to 3 (4–12 for risk), with total scores ranging from 7 to 21, with lower scores indicating greater risk |

Gap in expectation and understanding chronic pain

A cataclysmic gap remains between the societal expectation of a rapid ablation of pain and the current neuroscience model of chronic pain as a complex, multifactorial neurosensory and emotional phenomena. Within this deep trench may be the seed and soil on which CNCP and subsequent OS has escalated out of control. The growth of quick fix pain clinics in the United States over the past decade has created an iatrogenic-induced, pathologic, pain treatment thinking process. Expectation is frequently discordant from real outcomes in chronic pain. Spinal injection therapy alone for chronic back pain has not met acceptable benchmarks for enhanced outcomes for chronic low-back pain. However, this has not curbed the enthusiasm or popularity of these interventional therapies. The practice of fluoroscopically guided interventional procedures has increased by 159% between 2000 and 2010 alone. Clinics focused on procedural interventions only, and/or opioid dispensing, providing only a narrow spectrum of medical and behavioral support for the treatment of complex CNCP have fanned the flames of many seeking immediate gratification in pursuit of instant pain relief. This type of flawed thinking on behalf of patients and practitioners can lead the patient with CNCP to perceive that extrinsic or passive therapeutics, in the form of a procedure or a medication, have greater potential to heal, or fix what is likely thought of as broken, than intrinsic or lasting means. Self-actualization of change and acceptance of the limitations in correcting altered anatomy through well-directed physical, emotional, and cognitive behavioral adaptations may be the cornerstone of chronic pain rehabilitation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree