Operative Treatment of Tuberosity Fractures, Malunions, and Nonunions

Edward V. Craig

FRACTURES OF THE GREATER TUBEROSITY

Indications/Contraindications

Fractures of the greater tuberosity continue to present a challenge for the clinician treating trauma to the shoulder. Because of the small amount of space available to the rotator cuff passing under the coracoacromial arch, small degrees of tuberosity displacement may produce severe functional deficits (1).

Greater tuberosity fractures occur both in association with and in the absence of anterior glenohumeral dislocations (2, 3, 4). A greater tuberosity fracture without an associated dislocation may be nondisplaced, minimally displaced, or displaced. When displacement occurs, it is usually posterior or superior. In some instances, “open-book” displacement occurs with opening anteriorly and the fragment “hinged” posteriorly.

A greater tuberosity that fractures in association with an anterior glenohumeral dislocation may produce unique problems for the surgeon (5). If the associated soft-tissue attachments to the shaft of the humerus and periosteum are disrupted, the rotator cuff attached to the greater tuberosity may displace the greater tuberosity in such a way that when the humeral head is relocated, anatomic restoration of the greater tuberosity may not occur. If the greater tuberosity remains in an anatomic position following relocation, there is little long-term deficit. After a brief period of immobilization, rehabilitation may be begun with range-of-motion exercises, followed by exercises that are more aggressive after the healing of the fracture.

My indications for operative fixation of an isolated acute greater tuberosity fracture with or without an associated humeral head dislocation are the following:

1. Displacement of the greater tuberosity in a posterior direction more than 1 cm (Figs. 35-1 and 35-2).

2. Displacement of the greater tuberosity 0.3 to 0.5 cm in a superior direction in an overhead athlete or in someone who needs normal, asymptomatic function for overhead use of the arm.

3. Irreducible dislocation of the humeral head requiring open reduction.

In general, the only contraindications for acute operative treatment of a greater tuberosity fracture are little or no displacement of the tuberosity segment; displacement that is neither posterior nor anterior, but directly lateral, or hinges open on one side; or if the patient’s medical condition precludes surgical intervention.

Preoperative Planning

A patient who has a displaced greater tuberosity fracture, whether or not the humeral head is dislocated, presents with the arm splinted at the side. Any movement of the arm is exquisitely tender and painful. Examination of the extremity usually shows ecchymosis and swelling over the shoulder girdle, and there is often crepitus with gentle rotation of the glenohumeral joint. There is usually point tenderness in the area of the greater

tuberosity attachment. If the greater tuberosity fracture is accompanied by an anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint, there is, in addition, a fullness in the subcoracoid area. As in any anterior dislocation, there may be a flattening lateral to the acromial process, but the associated fracture of the tuberosity, with its attendant bleeding and swelling, may mask the usual flattened appearance, the result of the empty glenoid that frequently accompanies traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder.

tuberosity attachment. If the greater tuberosity fracture is accompanied by an anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint, there is, in addition, a fullness in the subcoracoid area. As in any anterior dislocation, there may be a flattening lateral to the acromial process, but the associated fracture of the tuberosity, with its attendant bleeding and swelling, may mask the usual flattened appearance, the result of the empty glenoid that frequently accompanies traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder.

I routinely order three radiographs to assess the degree of displacement of the greater tuberosity in an acute fracture: an anteroposterior (AP) view of the glenohumeral joint, which provides information on the degree of superior displacement of the greater tuberosity and identifies the proximity of the greater tuberosity to its donor fracture site; a true lateral view of the scapula, which gives information about the extent of superior and posterior displacement of the greater tuberosity segment and the degree of comminution of the fragment; and an axillary view, which demonstrates the presence or absence of an associated glenohumeral joint dislocation, gives some information on the extent of posterior displacement of the greater tuberosity segment, and may show any associated fracture of the glenoid that accompanies a fracture dislocation. Additionally, I usually order a computed tomography (CT) scan of the involved shoulder with or without 3-D reconstruction. The CT scan shows precisely the location of the greater tuberosity donor site and provides invaluable information about the degree of posterior displacement of the greater tuberosity segment. In addition, accompanying scapula (glenoid) pathology is well seen.

Occasionally, one may identify a greater tuberosity segment that is quite small and appears to be only one of the facets of rotator cuff attachment. This may be accompanied by a more severe soft-tissue injury, such as fullthickness tear of the rotator cuff, consisting of the supraspinatus and all or some of the external rotators. In this instance, the supraspinatus and infraspinatus may be torn at their insertions. Instead of the teres minor tearing, this tendon may avulse the small segment of bone visible radiographically. Thus, the radiographically evident piece of bone represents a much more significant soft-tissue injury. If, following reduction of the humeral head and near-anatomic restoration of the greater tuberosity segment, there is significant weakness, as one might find with a cuff tear, it may be reasonable to consider a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan instead of a CT scan, as this may provide information of associated soft-tissue damage and the extent of bony pathology accompanying the fracture.

Fractures of the greater tuberosity of the humerus that accompany more complex three- and four-part proximal humeral displacement are usually treated based on the entire fracture pattern and may include percutaneous fixation, locking plate fixation, or arthroplasty, whether hemiarthroplasty or reverse shoulder prosthesis.

Surgery

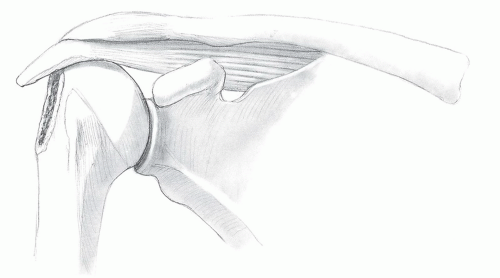

The patient is brought to the operating room and placed in a semisitting, beach-chair position. As with most shoulder procedures, the involved extremity is draped free. For an acute fracture, the incision is an anterosuperior one, extending from just lateral to the anterior acromion to just lateral to the coracoid process (Fig. 35-3). The subcutaneous tissue is then sharply divided in line with the skin incision, flaps are developed, and retractors are placed.

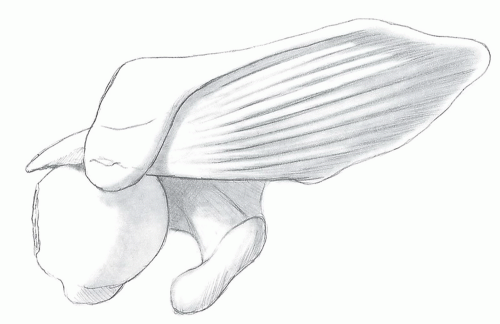

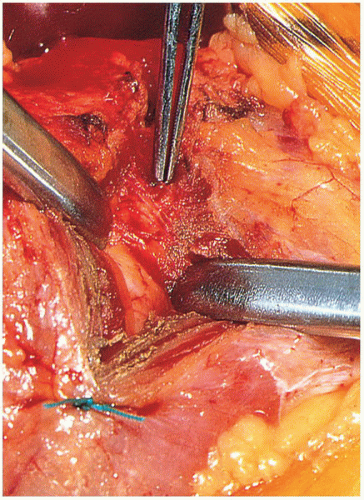

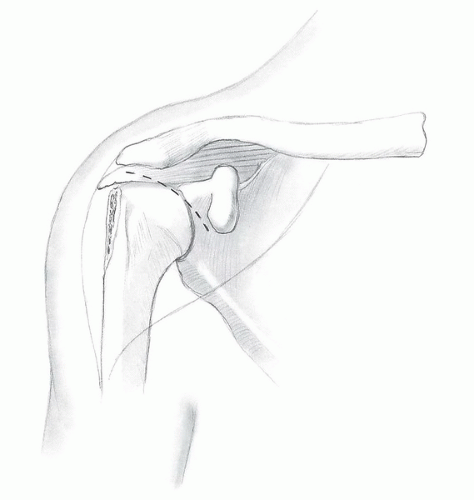

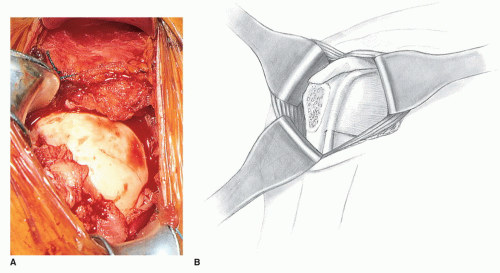

With an acute greater tuberosity fracture, under most circumstances, the open reduction and internal fixation can be performed by splitting the deltoid muscle. A vertical split is made in the deltoid muscle at the anterolateral corner in the raphe between the anterior and middle deltoid (Fig. 35-4),whether the displacement is superior or predominantly posterior (Fig. 35-5). The split in the deltoid does not extend longer than 4 to 5 cm to avoid injury to the terminal branch of the axillary nerve. A stay suture is placed in the deltoid muscle to prevent further splitting during retraction. The fibers of the deltoid are retracted and a blunt instrument is used to free the subdeltoid area of any adhesions and to ensure that free access to the greater tuberosity segment is achieved. Blood, clot, and debris are removed from the subacromial space, and a bursectomy is performed. The donor site from the area of the greater tuberosity adjacent to the bicipital groove is identified and clot is removed from this area as well. For access to the greater tuberosity segment and for ease of mobilization of the segment, several stay sutures are placed at the greater tuberosity-cuff junction (Fig. 35-6). This provides good control of the greater tuberosity fragment. Traction on the sutures enables the tuberosity fragment to be manipulated into its anatomic location, particularly if a little external rotation is applied to the humerus.

Many methods of internal fixation have been described for acute fractures of the greater tuberosity, including suture fixation, screw and washer fixation, or humeral locking plate fixation (6, 7). If a screw is utilized, the screw may be drilled through the greater tuberosity segment in an inferomedial direction to engage the opposite cortex of the upper metaphysis of the humerus, or it may be drilled horizontally if bone purchase is secure (Fig. 35-7). One or more screws can be used, depending on the size, amount of comminution, and bone quality of the greater tuberosity piece.

Alternatively, heavy suture (or wire) can be used to secure the greater tuberosity segment to its donor site (Fig. 35-8). If a suture is to be used, no. 5 nonabsorbable suture is strong, secure, and easy to work with. Drill holes are made in the humeral shaft inferior to the donor site, several no. 5 Tevdek sutures are placed through these drill holes, and the sutures emerge from the cancellous donor site. Likewise, drill holes also may be made in the greater tuberosity segment itself. If bone quality is excellent, one or more suture anchors may be utilized to secure the tuberosity fragment to donor site.

The rent in the rotator interval between the supraspinatus and subscapularis (which invariably accompanies this injury) is repaired. Side-to-side closure of the rotator interval will take tension off the rotator cuff and the greater tuberosity fracture and will help to prevent retraction of the tuberosity piece while preparation is being made for open reduction-internal fixation. The no. 5 Tevdek suture that has been placed through the humeral cortex to emerge from the donor site is then brought through the greater tuberosity fragment from inside out, and the greater tuberosity fragment is anatomically positioned in the proximal humerus and tied with a no. 5 nonabsorbable suture or wire.

FIGURE 35-3 The incision for acute fracture internal fixation is an anterosuperior one, extending from just lateral to the anterior acromion to just lateral to the coracoid process. |

FIGURE 35-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|