Operative Treatment of Displaced Surgical Neck Fractures of the Proximal Humerus

Joseph Borrelli Jr

Charles N. Cornell

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Although most proximal humeral fractures occur in the elderly, a significant number also occur in younger individuals as well. When due to low-energy trauma many of these fractures are minimally displaced and stable, often allowing nonoperative management. However, when due to high-energy trauma, these fractures are generally significantly displaced, angulated, and malrotated and have fractures of the tuberosity and therefore benefit from operative intervention.

The Neer (1) classification system is commonly used to describe these fractures and is effective in relating both the severity of the injury and appropriate surgical management. In this system, the four anatomic regions of the proximal humerus (humeral shaft, humeral head, greater and lesser tuberosities) are identified, and the involvement of these structures in the fracture and degree of displacement are taken into consideration. Fractures therefore are generally classified as either one-, two-, three-, or four-part fractures, depending upon the number of fracture fragments present.

In this classification system, a fragment is considered displaced when it comes to rest 10 mm or more from its anatomic position or is angulated by more than 45 degrees from its original position (isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity may be an exception and may require operative reduction and fixation if superior displacement is 5 mm or more). One-part fractures are essentially nondisplaced fractures and are generally amenable to closed treatment. Two-part fractures can represent a variety of different fracture patterns, the most common of which has a displaced fracture of the surgical neck with the humeral head and tuberosities remaining intact but separated from the shaft. In three-part fractures, generally one of the tuberosities is fractured and displaced from the proximal humerus and the head and remaining tuberosity is displaced from the shaft. Four-part fractures involve separation of both tuberosities from the head, as well as displacement of the head (either with a fracture of the surgical or anatomic neck) from the shaft.

The classification also describes those injuries associated with dislocation of the head from the glenoid, in addition to a combination of fractures, and identifies these as having a significantly worse prognosis. It is apparent that the greater the number of fragments in a fracture, the greater the risk of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the

humeral head. As a result, three- and four-part fractures have the highest risk of AVN. For quite some time, it was widely accepted that most two- and only some three-part fractures were best treated with internal fixation, while some three- and most four-part fractures were best treated with prosthetic replacement. One exception to this rule was valgus-impacted four-part fractures in young patients with good bone stock. Surgical repair of these fractures have been associated with predictable success. With the advent of locking plate technology in general, and proximal humeral locking plates in particular, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of nearly all displaced proximal humeral fractures is becoming more common and the functional outcome of these patients seems to be improving as a result.

humeral head. As a result, three- and four-part fractures have the highest risk of AVN. For quite some time, it was widely accepted that most two- and only some three-part fractures were best treated with internal fixation, while some three- and most four-part fractures were best treated with prosthetic replacement. One exception to this rule was valgus-impacted four-part fractures in young patients with good bone stock. Surgical repair of these fractures have been associated with predictable success. With the advent of locking plate technology in general, and proximal humeral locking plates in particular, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of nearly all displaced proximal humeral fractures is becoming more common and the functional outcome of these patients seems to be improving as a result.

It is now widely accepted that most unstable two-, three-, and four-part fractures are best managed with surgical intervention to restore useful shoulder function. Few patients, regardless of age or associated medical conditions, will not benefit from surgical treatment of an unstable proximal humerus fracture. Specific indications for ORIF include open fractures, those that cannot be reduced closed, and fractures with associated neurovascular compromise and those that are not amenable to closed reduction and percutaneous fixation. Young patients with good bone stock, especially those with multiple injuries who may need to rely more on their upper extremities (UE) for ADLs, are also excellent candidates for ORIF with locking plates. Specific contraindications to surgery occur in patients with little hope of functional recovery, such as debilitated elderly patients or those with neurologic lesions that preclude useful muscle function of the extremity. The presence of severe rotator cuff arthropathy is a relative contraindication to repair and may be an indication for prosthetic shoulder replacement.

In recent years, lack of predictability in greater tuberosity healing in fractures of the elderly has resulted in some advocating primary reverse arthroplasty in acute four-part fractures in the elderly. The rationale is that lack of greater tuberosity healing can dramatically effect shoulder function adversely, and the reverse prosthesis is predominantly deltoid powered, making tuberosity healing, while desirable, not essential for a functioning shoulder.

Most proximal humeral fractures occur in elderly women after low-energy single-level falls. Generally, the bone of the proximal humerus is osteoporotic and provides for poor fixation when conventional plates and screws are used (2, 3). Hawkins et al. (2, 3) pointed out that the soft-tissue attachments of the rotator cuff tendons are usually strong in spite of poor adjacent bone quality. They demonstrated that these soft tissues provide excellent sites of fracture fixation when tension band wiring techniques are used. Furthermore, tension band wiring does not violate the subacromial space or lead to postoperative impingement and minimizes the stripping and interference with blood supply associated with plates. Nowadays, it is common for the proximal humeral locking plates to be used, with or without tension band wiring techniques, to address these injuries in the elderly. In younger patients, bone quality is usually superior, and this allows excellent fixation with plates (locking or nonlocking) and screws. Fractures in young patients that occur as a result of high-energy trauma can have severe metaphyseal comminution making repair more difficult. This metaphyseal comminution creates instability that precludes the use of the isolated screw and tension band technique, as it leads to excessive shortening with loss of deltoid power and inferior subluxation of the humeral head. In such cases, plates are needed to restore and maintain the normal length of the humerus. In the past, small fragment plates such as the cloverleaf plate were found to fit the proximal humerus well and provided for multiple screw purchase in the humeral head. Well-contoured locking plates that have a low profile have more or less replaced the use of conventional plates for the treatment of these difficult fractures. In many cases, a tension band wiring can be used in conjunction with plates to help neutralize the pull of the rotator cuff, which can significantly enhance the security of the fixation. In summary, two-part fractures (generally the greater or lesser tuberosity) in both young and old patients without significant comminution can usually be managed with a tension band wiring technique. Three- and four-part fractures, proximal humeral nonunions, and fractures with metaphyseal comminution are better treated with precontoured specialty plates featuring locking screw technology possibly in combination with tension band wiring technique.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

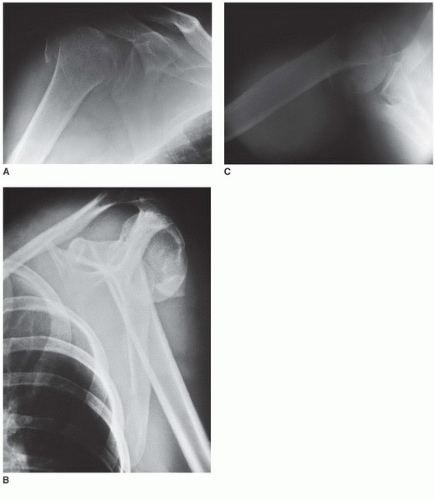

In patients with injuries to the shoulder, a careful history should be taken to document the mechanism of injury as well as the presence of associated injuries. The physical examination should assess the degree of swelling and include a careful search for ipsilateral neurovascular injury including injury to the axillary nerve and the presence of an open fracture. Although vascular injury is rare, axillary artery disruption does occur and is most commonly associated with numbness and paresthesia in the ipsilateral hand as a result of a concomitant neurologic injury. Vascular disruption can also be associated with excessive bruising and an expanding axillary hematoma. Because the collateral circulation of the upper limb is extensive, the presence of pulses at the wrist does not preclude the presence of a significant proximal vascular injury. The axillary and musculocutaneous nerves are the most commonly injured nerves, and their function at the time of presentation must be carefully documented. Radiographs should include a true anteroposterior and a transthoracic lateral of the shoulder, as well as an axillary view of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 32-1A-C). If significant

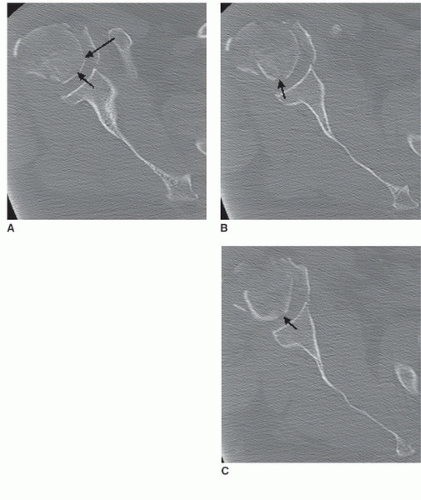

comminution of the proximal humerus is present, and particularly if a hemi-shoulder arthroplasty is being considered, full-length views of the contralateral humerus are also necessary. If there is a question of comminution of the humeral head, or if the precise location and pattern of the tuberosities fracture is unclear, a CT scan of the shoulder should also be obtained (Fig. 32-2A-C). Arteriography or MRI arteriography may be helpful in localizing major vessels in anticipation of surgical approach if displaced fragments to be secured are in proximity to major vessels.

comminution of the proximal humerus is present, and particularly if a hemi-shoulder arthroplasty is being considered, full-length views of the contralateral humerus are also necessary. If there is a question of comminution of the humeral head, or if the precise location and pattern of the tuberosities fracture is unclear, a CT scan of the shoulder should also be obtained (Fig. 32-2A-C). Arteriography or MRI arteriography may be helpful in localizing major vessels in anticipation of surgical approach if displaced fragments to be secured are in proximity to major vessels.

While awaiting surgical intervention, the surgeon should develop a careful preoperative plan including a surgical tactic to assure that each fracture fragment has been identified and considered, and to assure that the necessary instruments and implants will be available during surgery. A surgical drawing should trace the preoperative location of the humeral head, shaft, and greater and lesser tuberosities. A second drawing is prepared to locate the position of the fragments after open reduction is performed. The position of the plate and screws and possible tension band wires/sutures is included in this second drawing. New computer software is now available to allow preparation of a digital preoperative plan.

The surgical approach to a proximal humerus fracture is traditionally carried out through a deltopectoral approach or possibly a deltoid splitting approach (4, 5). Swelling, and hematoma, as well as disruption of the bony landmarks can frustrate even experienced surgeons; therefore, familiarity with the local anatomy will help reduce the operative time for some of these challenging fractures. Hasty preparation will lead to longer operative time and a much more frustrating learning curve with this technique.

SURGERY

Patient Positioning and Surgical Approaches

Regional anesthesia, combined with general anesthesia, is frequently used for this procedure. Interscalene block can usually provide adequate anesthesia and can provide postoperative pain relief if long-acting local anesthetics are used. The surgeon can supplement the block with local anesthetics and epinephrine to provide adequate cutaneous anesthesia and to retard bleeding from the skin and subcutaneous tissues during the surgical exposure. An interscalene block may paralyze the ipsilateral diaphragm, which can lead to respiratory distress in patients with severe preoperative pulmonary compromise, and should be used with caution.

To allow use of the image intensifier during the procedure, the patient must be carefully positioned. A radiolucent table and a “beanbag” are helpful. The patient is positioned in the beach-chair position with the head elevated 60 to 75 degrees; the shoulder should project off the side of the table, which will allow access for the image intensifier. A beanbag is necessary to hold and secure the patient in this position. The affected arm is draped free with access from the base of the neck to allow an extended deltopectoral incision. An interscapular pad and careful molding of the beanbag medial to the scapulae body are needed to allow manipulation of the arm and shoulder during the procedure. The image intensifier should be positioned at the head and parallel to the side of the operating room table (Fig. 32-3A). Once the patient is positioned, care should be taken to assure circumferential visualization of the shoulder. The deltopectoral incision is made, beginning just lateral to the palpable coracoid process and extended distally and lateral to the level of the deltoid insertion. The cephalic vein within the deltopectoral interval should be identified and retracted laterally within the deltoid muscle, though it may be sacrificed. Once the interval between the pectoralis major and the deltoid muscle has been developed, the biceps tendon should be identified distally and followed proximally to the rotator cuff interval. The overlying clavipectoral fascia should be incised and the rotator cuff and tuberosities exposed. The anterior portion of the distal deltoid insertion should be carefully elevated to facilitate retraction of the deltoid thus

improving exposure of the proximal humerus and rotator cuff. A portion of the pectoralis major insertion can also be released longitudinally in line with the long axis of the humerus, after which the shoulder can be gently abducted. A variety of shoulder-specific retractors can then be placed beneath the deltoid and posterior to the humeral head to improve exposure of the proximal humerus and the different fracture fragment with the arm abducted (Fig. 32-4).

improving exposure of the proximal humerus and rotator cuff. A portion of the pectoralis major insertion can also be released longitudinally in line with the long axis of the humerus, after which the shoulder can be gently abducted. A variety of shoulder-specific retractors can then be placed beneath the deltoid and posterior to the humeral head to improve exposure of the proximal humerus and the different fracture fragment with the arm abducted (Fig. 32-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree