Open Surgical Reconstruction of Acute and Chronic Acromioclavicular Joint Instability

Augustus D. Mazzocca

Cory M. Edgar

Knut Beitzel

Andreas B. Imhoff

Thomas M. DeBerardino

Robert A. Arciero

HISTORICAL CONTEXT FOR DEVELOPMENT OF SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint dislocations have been a topic of interest and treatment controversy since the writings of Hippocrates and Galen (1). A variety of closed reduction maneuvers and splinting techniques have been described with mixed results. Bracing may be painful and poorly tolerated, leading to residual instability and possibly chronic pain or dysfunction. Since the first reported surgical treatment of a displaced AC joint in 1861 by Samuel Cooper, more than 60 techniques have been described to stabilize the joint, including numerous direct repair or reconstructive procedures for both the AC and coracoclavicular (CC) ligaments (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Injuries to the AC joint are one of the more common shoulder injures sustained during athletic participation. It is typically a result of a direct trauma to the superior aspect of the shoulder driving the scapula downward and

medial (3, 4, 5). Using the Rockwood classification, type I and II injuries are universally treated nonoperatively, while type IV, V, and VI injuries have been consistently managed with surgical repair or reconstruction (1). The area of persistent controversy concerns management of type III injuries especially acutely in the active patient. Indications for surgical treatment are typically related to joint instability, persistent pain, or changes in shoulder biomechanics that can affect sport or daily activity. A thorough understanding of the relevant anatomy and structures responsible for AC joint stability as well as an understanding of the historical progression of surgical solutions to treat these injuries is important in providing the optimum treatment.

medial (3, 4, 5). Using the Rockwood classification, type I and II injuries are universally treated nonoperatively, while type IV, V, and VI injuries have been consistently managed with surgical repair or reconstruction (1). The area of persistent controversy concerns management of type III injuries especially acutely in the active patient. Indications for surgical treatment are typically related to joint instability, persistent pain, or changes in shoulder biomechanics that can affect sport or daily activity. A thorough understanding of the relevant anatomy and structures responsible for AC joint stability as well as an understanding of the historical progression of surgical solutions to treat these injuries is important in providing the optimum treatment.

The AC joint is a true diarthrodial joint with a thin cartilage surface with an interposed fibrocartilaginous meniscoid disk. Static stability comes from capsular thickenings or ligaments and two extracapsular CC ligaments: the conoid and trapezoid. Cadaveric sectioning studies estimate the AC ligaments to contribute 20% to 50% of resistance to superior migration but 90% to clavicular translation in the sagittal plain (anterior/posterior) (6, 7, 8). The CC ligaments are the primary restraint to inferior and medial translation of the scapulohumeral complex in relation to the clavicle and axial skeleton. Specifically, the conoid ligament tensions under loads that displace the clavicle superiorly, and the trapezoid tensions during compression of the AC joint or medialization of scapulohumeral complex (6, 7). Failure of one ligament complex increases strain on the remaining static restraints. Not to be underestimated is the dynamic stability to the AC joint provided by the deltotrapezial fascia, specifically the anterior deltoid insertion on the anterolateral boarder of the clavicle and AC joint.

With the progression of technology and its application to surgical improvements of AC joint injuries, the treatment of complete AC joint separations has transitioned from conservative to operative management over the years (1). The surgical treatment of AC joint dislocations has a clear historical progression. Intra-articular fixation of the AC joint with pins/wires was among the first techniques to be described. Fixation was meant to provide an enhanced temporary reduction allowing the native soft tissue an opportunity to heal anatomically. However, reports of fixation failure, loss of reduction, and disastrous migration of hardware led to abandonment of this technique. Extra-articular fixation followed and is best illustrated by the Bosworth “screw suspension” technique. As described in 1941, it was meant to provide stability to facilitate CC ligament healing, but again hardware failure, migration, and coracoid fractures associated with the use of this device led to the development of alternative “CC suspension” constructs, including Dacron grafts, wires, and various types of sutures. Distal clavicle excisions were reported by Mumford and Gurd independently in 1942 as a means to address painful type II AC joint (Mumford) or type III (Gurd) injuries. However, the instability of the AC joint is not addressed by these procedures. In 1972, Weaver and Dunn published their technique of distal clavicle resection and transfer of the coracoacromial ligament to restore and reconstruct the CC ligaments and treat acute and chronic AC joint instability. Over the years, numerous modifications to this technique have been described (1, 2).

The first attempt at the reconstruction of the CC ligaments was reported in 1942 by Vargus, describing transfer of part of the conjoined tendon anterior to the clavicle. Anatomic reconstruction of the native CC ligaments and AC ligaments represents an improved understanding of the biomechanics in this area with the possibility of improved surgical outcomes. The Anatomic Coracoclavicular Ligament Reconstruction (ACCR) Technique described here attempts to restore the biomechanics of the AC joint complex for the treatment of painful or unstable dislocations. This technique has been previously reported during various stages of its development, and this technique represents the final progression of its development (9, 10, 11, 12).

INDICATIONS AND PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

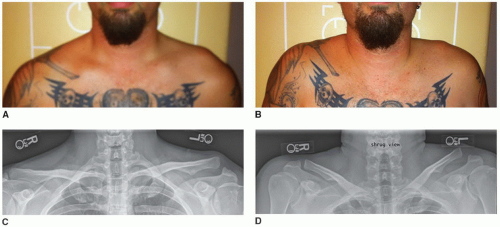

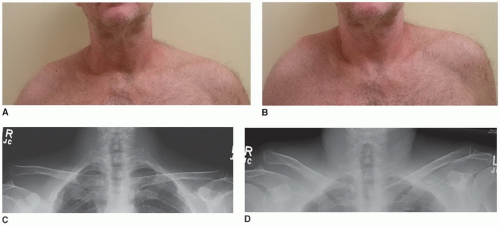

There is a consensus that lower grade injuries, type I and II, can be treated nonoperatively with low incidence of chronic pain or disability. Likewise, the significantly displaced injures to the AC joint complex with complete disruption of AC joint and CC ligamentous complex and involving greater than 300% displacement of the clavicle, threatened skin, or an irreducible AC joint warrant surgical treatment. In these situations, this technique can be applied acutely. Controversy still remains regarding the treatment of type III injuries. To further complicate the issue, the best clinical method of determining a type III from a type V injury has not been elucidated. From a clinical perspective, the ability to reduce the scapula to the clavicle has been described as an indication of injury gradation. The assumption is if the deltotrapezial fascia is still intact then reduction is usually possible. Therefore, reducibility correlates with intact overlying fascia and type III injury (12, 13). Conversely, inability to reduce the joint may be caused by “buttonholing” of the clavicle through a ruptured fascial layer. The “Shrug test” is described as an attempt at providing a radiographic distinction between these two injuries, as exemplified by its use in a type III and type V injury (Figs. 18-1 and 18-2). Using the Zanca view, radiographs are taken during an active shoulder shrug. AC joint congruity, reduction, and CC distance are measured to a radiograph obtained pre- and postshrug. In our current experience, clinical reduction does not correlate with radiographic AC joint reduction, and this finding has not been helpful in planning clinical treatment.

An important consideration in the preoperative planning is the radiographic assessment of the injured and uninjured AC joint complex. We commonly obtain bilateral standing Zanca view films (x-ray beam 10 to 15 degrees caudad to cephalad, using one-half of the standard penetrance) to directly measure CC distance side to side. This is performed with the patient standing, arms at the side without any weights or support.

Additionally, an axillary lateral radiograph is taken to determine the sagittal position of the distal clavicle. Stryker notch radiographs can be taken to rule out a coracoid fracture, and, if present, CC ligament reconstruction is contraindicated. A coracoid fracture is most commonly seen when there is superior displacement of the clavicle with minimal change in the CC distance from the uninjured side.

Additionally, an axillary lateral radiograph is taken to determine the sagittal position of the distal clavicle. Stryker notch radiographs can be taken to rule out a coracoid fracture, and, if present, CC ligament reconstruction is contraindicated. A coracoid fracture is most commonly seen when there is superior displacement of the clavicle with minimal change in the CC distance from the uninjured side.

Prior to surgical reconstruction, it is important to determine if any glenohumeral pathology coexists. SLAP lesions and biceps tendon injuries must be ruled out as they can also be found in the same patient populations following similar injuries, and pain originating from the superior anterior shoulder can be difficult to localize. The innervation of the AC joint and glenohumeral joint is from the lateral pectoral and suprascapular nerves. In a study by Gerber in 1998, it was suggested that irritation to the AC joint produced pain over the AC joint, in the anterolateral neck and in the region in the anterolateral deltoid. Glenohumeral or subacromial space produced

pain in the region of the lateral acromion and the lateral deltoid muscle but did not produce pain in the neck or trapezius region, so clearly directed questioning about pain localization may differentiate. A careful history and evaluation of the mechanism of injury are also critical. Provocative maneuvers, like cross-arm adduction, lidocaine injections, and direct palpation, are important differentiation tools (4).

pain in the region of the lateral acromion and the lateral deltoid muscle but did not produce pain in the neck or trapezius region, so clearly directed questioning about pain localization may differentiate. A careful history and evaluation of the mechanism of injury are also critical. Provocative maneuvers, like cross-arm adduction, lidocaine injections, and direct palpation, are important differentiation tools (4).

At the University of Connecticut, all acute type I, II, III, and V injuries are managed with a 6-week course of supervised rehabilitation to maximize rotator cuff strength and the stabilizing function of the periscapular muscles (14). Altered shoulder biomechanics leading to symptoms can be the sequelae of complete AC joint displacement. A recent study estimated that 70% of patients with type III injuries had scapular dyskinesis and, eventually, SICK scapula syndrome (Scapular malposition, Inferior medial border prominence, Coracoid pain and malposition, and dyskinesis of scapular movement) developed in 54% of patients with chronic type III AC dislocations (15, 16). If pain or disability persists following rehabilitation and conservative treatment, surgical reconstruction is discussed. However, the open ACCR surgical technique could be applied to the treatment of acute significantly displaced injuries in the young active patient if conservative treatment is not appropriate given displacement or instability.

SURGERY: ANATOMIC CORACOCLAVICULAR LIGAMENT RECONSTRUCTION (DR. MAZZOCCA AND ARCIERO TECHNIQUE)

Patient Positioning

The procedure is performed in the beach-chair position with the hip flexed to 60 to 70 degrees and the patient positioned far lateral on the bed to allow the arm to fall into extension. This facilitates exposure and mobilization of the shoulder for scapula reduction to the clavicle. A small towel bump is placed along the medial boarder of the scapula to prevent protraction of the scapula. In addition, this elevates the torso away from the table thereby improving access to the clavicle for drilling the bone tunnels. Gently rotating the patient’s head away from the operative field with some extension aids in exposure (Fig. 18-3). Care should be taken to not be overly aggressive with this maneuver and to provide enough support to ensure there is not excessive tension to the brachial plexus during the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree