Open Repair of the Massive Rotator Cuff Tear

Gerald R. Williams Jr

Peter Johnston

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Massive rotator cuff tears have been defined as having maximum retraction of greater than 5 cm or involvement of two or more tendons (1, 2). Massive tears constitute approximately 10% of the patients in most reported series from tertiary centers (1). Prognosis following rotator cuff repair has been correlated with preoperative rotator cuff tear size, with massive tears having the highest rerupture rate and lowest patient-derived outcome among rotator cuff tears of all sizes (2, 3). Although tear size is an important predictor of clinical outcome following rotator cuff repair, several other factors may also exert prognostic influence and therefore be important in determining surgical indications and contraindications. These factors include patient age, medical comorbidities, smoking, tear chronicity, muscle atrophy or fatty degeneration, and glenohumeral stiffness. Detailed history, physical examination, and radiographic evaluation allow for an accurate diagnosis and at least an estimation of prognosis following repair. Table 26-1 summarizes these influential factors and their effects on prognosis following cuff repair.

Indications for repair of a massive rotator cuff tear vary greatly, based upon the factors mentioned above. In the absence of a traumatic injury, a 3- to 6-month trial of nonoperative management in the form of activity modification, physiotherapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and occasional corticosteroid injections is warranted. This is especially true in patients over the age of 70 or in those patients who use tobacco, have multiple medical comorbidities, or have fatty degeneration of their rotator cuff muscles of grade 2 (equal fat and muscle) or greater (4, 5).

However, if the history includes a recent (within 3 to 6 weeks) injury, especially if the injury was followed by a noticeable decrease in shoulder strength and function, early repair should be considered results following early repair of rotator cuff tears with a traumatic history are better than late repair (6, 7). Moreover, laboratory data suggest that, for reasons not entirely understood, rotator cuff repair tension does not increase linearly from the time of injury. Rather, at least in lab animals, it increases dramatically in the first 3 weeks and continues to increase slowly over time (8). If the massive tear is truly acute, as evidenced by no prior shoulder symptoms and imaging studies that reveal no atrophy or fatty degeneration, repair at the earliest convenience (days or weeks, not months) is indicated. This affords the best prognosis, especially if the patient is young, does not smoke, and has no or minimal medical comorbidities.

Although acute tears are relatively uncommon, acute-on-chronic rotator cuff tears occur frequently and are often underappreciated. The differences in presentation between patients with an acute-on-chronic versus an acute massive tear can be subtle. Both will give a history of recent injury with new onset of shoulder weakness and decreased function. A history of prior episodes of “bursitis” or “tendonitis” may suggest that the tear has a chronic component. However, given that the incidence of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears can be as high as 50% to 60% and increases with age, it is possible that older patients with an acute-on-chronic rotator cuff tear may have had no symptoms prior to the recent injury. The only evidence that a chronic tear existed to some degree before the injury is visible atrophy on physical examination or atrophy and/or fatty degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasound.

The indication for surgery in a patient with a massive, acute-on-chronic rotator cuff tear depends considerably on what percentage of the tear the surgeon thinks occurred acutely and the age and activity level of the patient. Unfortunately, there is no reliable method for determining precisely how much of the tear was chronic

and how much occurred acutely. However, some clinical and imaging clues may be helpful. First, patients whose tears were mostly chronic before an acute injury will often demonstrate relatively rapid (within 2 to 4 weeks) return of function. In addition, the degree of atrophy and/or fatty degeneration as seen on MRI scanning will be relatively consistent across all muscles involved with the tear. A common scenario is a 70-year-old patient who falls and is unable to raise his or her arm. An MRI may reveal full-thickness tears of the supra- and infraspinatus tendons with retraction and stage 2 fatty degeneration of both muscle bellies. Two to four weeks of physiotherapy may result in much less pain and weakness with restoration of the overhead function.

and how much occurred acutely. However, some clinical and imaging clues may be helpful. First, patients whose tears were mostly chronic before an acute injury will often demonstrate relatively rapid (within 2 to 4 weeks) return of function. In addition, the degree of atrophy and/or fatty degeneration as seen on MRI scanning will be relatively consistent across all muscles involved with the tear. A common scenario is a 70-year-old patient who falls and is unable to raise his or her arm. An MRI may reveal full-thickness tears of the supra- and infraspinatus tendons with retraction and stage 2 fatty degeneration of both muscle bellies. Two to four weeks of physiotherapy may result in much less pain and weakness with restoration of the overhead function.

TABLE 26-1 Prognostic Factors Affecting Outcome of Open Repair of Massive Cuff Tears | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conversely, a patient may present with new onset of shoulder weakness and inability to raise the arm following an injury with an MRI that shows a tear involving all of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons with stage 2 atrophy of the supraspinatus and stage 0 or 1 atrophy of the infraspinatus. This suggests that the chronic tear did not involve the infraspinatus to the same degree as the supraspinatus. It is likely that the weakness and decrease in shoulder function will persist beyond 2 to 4 weeks, despite physiotherapy.

These two scenarios represent two extremes of the presentation spectrum. The first is an example of a predominantly chronic tear with mild acute extension. In general, it should be treated like a chronic tear with surgery reserved for patients who do not respond to nonoperative treatment of 3 to 6 months. The second scenario represents a small chronic tear with substantial acute extension. This tear should be treated more like an acute tear with consideration for early (weeks not months) repair. Unfortunately, most patients with massive, acuteon-chronic rotator cuff tears present somewhere between these two extremes. The decision for surgery is often difficult and should be individualized. In young, active patients—particularly those with minimal atrophy, no smoking history, and minimal comorbidities—surgery is considered more strongly. A useful historical question may help the clinician. Despite MRI evidence of chronicity, the patient may give the history of little trouble and good function of the arm until the recent trauma, after which there was an inability to raise the arm. This may be an important clue to an acute-on-chronic tear.

In the past, repair of massive rotator cuff tears in combination with rotator cuff allograft or synthetic material was described as a means of reinforcing the repair and improving results (9, 10, 11, 12). This really never became common practice, presumably because the results did not justify it. More recently, the concept of reinforcement of rotator cuff repairs with a patch has been revisited. Many types of patches have been suggested including allograft dermis, xenografts, and synthetic scaffolds (13). A detailed discussion of these patches is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, these patches differ in a number of ways, perhaps most importantly in their stiffness or strength and in their potential to stimulate biologic activity at the repair site. The addition of growth factors and/or stem cells has also been suggested. However, few to no data exist to indicate the efficacy of any of these patches or biologic amplification techniques. Therefore, the indications for these techniques are unclear. In my practice, the use of a biologically active patch is at least considered in young patients with chronic massive tears.

Since this is a chapter on open repair of massive rotator cuff tears, some discussion regarding the relative indications of open and arthroscopic repair is appropriate. There has been an undeniable trend from open to arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears over the last 10 to 15 years. Early results of arthroscopic repair yielded healing rates that were inferior to open techniques (14). However, as techniques and equipment have evolved, healing rates for open and arthroscopic repair have become closer. In fact, with small- to medium-sized tears, the reported rates of rerupture are approximately the same (15). Large and massive tears remain a challenge and results have been inconsistent, with some reports of rerupture following arthroscopic repair as high as 90% and others as low as 10% (14, 16). It is important to remember that open repair techniques have evolved over approximately 100 years and that arthroscopic repair has only been performed in any substantial numbers for 15 years. Arthroscopic results will undoubtedly continue to improve. Although open repair is uncommon in my practice, relative indications include chronic, massive tears in a young, active person and revisions of failed arthroscopic repairs of massive tears—especially if a reinforcing patch is being considered.

The only absolute contraindications to open repair of a massive rotator cuff tear are the presence of multiple medical comorbidities that prevent the patient from safely undergoing surgery and the inability or unwillingness

of a patient to accept the attendant risks and to comply with the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation. However, other relative contraindications may factor into the decision to recommend open repair of a massive rotator cuff tear. These include the presence of an irreparable tear, substantial glenohumeral arthritis, shoulder stiffness in the absence of glenohumeral arthritis, advanced age, and current tobacco use.

of a patient to accept the attendant risks and to comply with the postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation. However, other relative contraindications may factor into the decision to recommend open repair of a massive rotator cuff tear. These include the presence of an irreparable tear, substantial glenohumeral arthritis, shoulder stiffness in the absence of glenohumeral arthritis, advanced age, and current tobacco use.

Unfortunately, determining whether a specific rotator cuff tear is reparable preoperatively is difficult. Findings that may suggest an irreparable tear include fixed proximal humeral migration, large lag signs, and stage 3 or greater fatty degeneration. Even in the presence of these factors, an attempt at repair may be warranted in a young active patient, particularly if his or her livelihood depends on his or her shoulder. In this situation, a diagnostic arthroscopy with attempted arthroscopic mobilization and an assessment of reparability prior to performing the open repair may be useful.

Open repair of a massive rotator cuff tear in combination with radiographically apparent glenohumeral arthritis may be contraindicated. If the tear is chronic, consideration should be given to anatomic or reverse shoulder arthroplasty with or, more likely, without cuff repair. If the tear is acute, or acute-on-chronic, an attempted repair is usually indicated, especially if the patient is young and active. The decision to replace the shoulder, in addition to repairing the rotator cuff, should be individualized based on factors such as patient age and activity level and the presence of arthritic symptoms prior to the tear.

In the absence of glenohumeral arthritis, substantial stiffness in association with a massive rotator cuff tear may also be a contraindication to open repair. If the tear is acute or, more likely, acute-on-chronic, one may not get another opportunity to repair the rotator cuff after the stiffness has resolved. Therefore, repair combined with manipulation or capsular release should be considered. My preference is an arthroscopic capsular release and arthroscopic repair. However, others may prefer open repair with manipulation. If the tear is chronic, consideration for repair is delayed until the stiffness is resolved or maximally improved.

Rotator cuff repair healing rates correlate relatively strongly with patient age (17). Open repair of massive rotator cuff tears in patients over 70 years should be considered carefully because of the relatively high recurrence rate. Repair is indicated uncommonly. However, if an acute or an acute-on-chronic tear is diagnosed and is associated with new onset of profound weakness and loss of overhead function that persists despite a short course (2 to 4 weeks) of physiotherapy, early repair should at least be discussed with the patients—especially if they are healthy and physically active.

Tobacco use, like advanced age, has a negative effect on tendon healing. Therefore, the patient with a massive cuff tear that would otherwise be best managed surgically should be encouraged to quit smoking or use smokeless tobacco in the perioperative period. However, if they cannot or will not cease tobacco use, a discussion of the effects of tobacco use on the prognosis following repair should be had and the decision to proceed made collectively by the patient and surgeon. Some surgeons may consider smoking a contraindication to open repair of a massive tear.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative planning for open repair of a massive rotator cuff tear should include consideration of concomitant procedures such as acromioplasty, distal clavicle excision, and biceps tenodesis or tenotomy. The need for acromioplasty in association with repair of rotator cuff tears of all sizes has become controversial. Certainly, in the absence of a substantial spur, especially if the tear is acute with no prior shoulder symptoms, acromioplasty is probably not indicated. The evidence supporting acromioplasty when an acromial spur is present is mixed, with some authors recommending against acromioplasty in all cases and others recommending acromioplasty in cases of large (type 3) acromial spurs (3, 18, 19). Acromioplasty in conjunction with repair of a massive rotator cuff tear may theoretically lead to anterosuperior humeral subluxation with loss of overhead function, especially if the tear recurs and the coracoacromial ligament has been resected (20). Therefore, when acromioplasty is performed in conjunction with repair of a massive rotator cuff tear, care should be taken to avoid substantial shortening of the anteroposterior length of the acromion and the coracoacromial ligament should not be excised. In fact, repair of the coracoacromial ligament with the anterior deltoid may decrease the likelihood of postoperative anterosuperior escape (21).

Asymptomatic acromioclavicular arthropathy is common in the age groups most often affected by rotator cuff tears. Therefore, distal clavicle excision is only performed when arthritic changes are present in the acromioclavicular joint, the joint is tender to palpation, and cross-body adduction reproduces pain. In addition, acromioclavicular joint injection with local anesthetic, with or without corticosteroid, may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis when findings are unclear.

The long head of the biceps tendon may be a source of pain in patients with massive rotator cuff tears. In some cases, preoperative physical and MRI findings may suggest biceps pathology. However, biceps pathology is often not delineated with history, physical examination, or MRI scanning. Therefore, the patient should be made aware that biceps pathology will be investigated for at surgery, and the surgeon should be prepared to perform a tenodesis or tenotomy, depending on the patient’s wishes as discussed preoperatively. In most cases of open repair of massive rotator cuff tears with concomitant biceps pathology, biceps tenodesis is performed.

Open repair of massive rotator cuff tears is facilitated by the use of certain operative equipment. The presence of this equipment in the operating room should be confirmed during the course of preoperative planning.

This equipment includes an appropriate operating table, a mechanical arm holder or padded Mayo stand, specialized retractors, osteotomes, and a microsagittal saw and burr.

This equipment includes an appropriate operating table, a mechanical arm holder or padded Mayo stand, specialized retractors, osteotomes, and a microsagittal saw and burr.

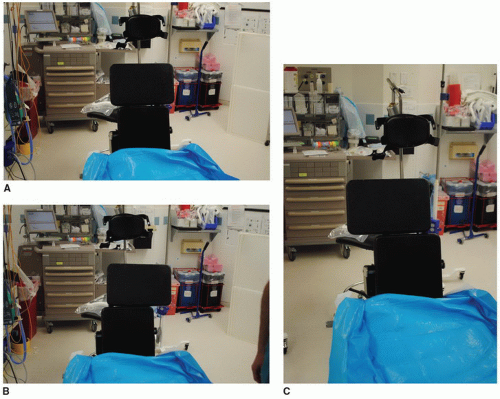

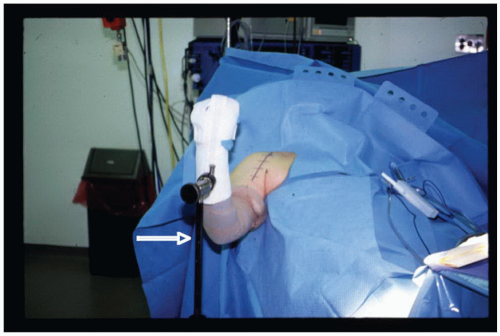

Proper completion of the cuff repair and any potential concomitant procedures requires access to the top, front, and back of the shoulder. This requires that the patient be positioned near the edge of a standard operating table or on a specialized operating table that features break away or moveable panels posterior to the shoulder (Fig. 26-1). In either case, a low-profile headrest can be helpful. In addition, the use of a mechanical arm holder (Fig. 26-2) that allows rotation and stabilization of the arm in multiple positions can assist with visualization of and access to the entire tear. Alternatively, a padded Mayo stand on which the arm rests can be used.

FIGURE 26-2 During surgery, the arm can be supported in any degree of elevation or rotation using a sterile mechanical arm holder (white arrow). (McConnell Ortho Manufacturing Co., Greenville, TX.) |

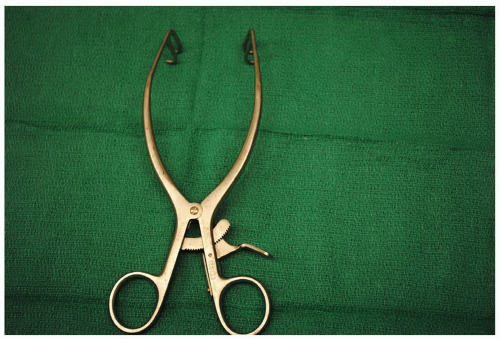

FIGURE 26-3 The double-pronged Gelpi retractor is useful for retracting the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It has blunt tips to avoid skin penetration. (Innomed, Savannah, GA.) |

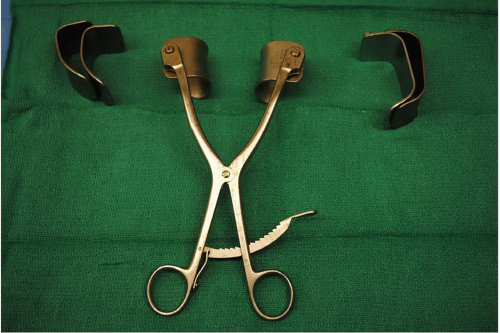

FIGURE 26-4 The Koebel retractor has small, medium, and large blades and is helpful for retracting the deltoid. Care must be used to prevent overzealous retraction. (Innomed, Savannah, GA.) |

Specialized self-retaining retractors can greatly improve visualization and are especially helpful if an assistant is not available. These retractors include a double-pronged Gelpi retractor for the skin and subcutaneous tissue, a Koebel retractor for the deltoid, and a modified laminar spreader to retract the humeral head inferiorly. The double-pronged Gelpi retractor (Fig. 26-3) has blunt tips to avoid penetration of the soft tissue. It can also be used to retract the deltoid once it has been split and detached from the anterior acromion. More extensive exposure of the humerus and rotator cuff can be accomplished with a Koebel retractor using the small or medium blades (Fig. 26-4). A laminar spreader that has been modified to have a ring on one side to apply to the humeral head while the other side is applied to the undersurface of the acromion can greatly facilitate visualization and access to the rotator cuff. Right- and left-side retractors are available (Fig. 26-5).

Multiple standard, commonly available operating tools are also helpful. A microsagittal saw and burr can be helpful in performing the acromioplasty, distal clavicle excision, biceps tenodesis, and tuberosity preparation. A large flat retractor, such as a Darrach, can be used to displace the humerus inferiorly when performing the acromioplasty. Crego elevators can be especially helpful in subperiosteally exposing the distal clavicle when excision is indicated. Various awls and drills facilitate cuff and deltoid repair.

Depending on the chosen method of repair, various implants, sutures, and free needles may be required. Potentially required implants include suture anchors, suture augmenting buttons or plates, and rotator cuff patches. I prefer open posterosuperior cuff repair with heavy nonabsorbable sutures through bone tunnels rather than with suture anchors. One potential suture is 1-mm Dacron tape (Deknatel, Fall River, MA). When extremely soft bone is encountered, a thin, fenestrated plate (G. HUG, Freiburg-Umkirch, Germany) can be used at the lateral humeral cortex to tie the sutures over (22). Large, cutting free needles can aid passage of the suture through bone during repair. If the subscapularis is involved, suture anchors may be used, as the bicipital groove may make passage of sutures tedious. If the decision has been made to use a reinforcing patch, its presence in the operating room should be confirmed preoperatively.

FIGURE 26-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|