Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Pediatric T-Condylar Fractures

Keith D. Baldwin

John M. Flynn

DEFINITION

T-condylar fractures of the distal humerus in children and adolescents are relatively rare occurrences. They are thought to represent 2% of all pediatric elbow fractures.5

The proposed mechanism is similar to that of pediatric supracondylar fractures but with a higher energy mechanism of injury.6

The olecranon acts as a wedge during hyperextension and creates a Y- or T-shaped fracture with the center in the olecranon fossa.

These fractures are less likely to be comminuted than in adults.

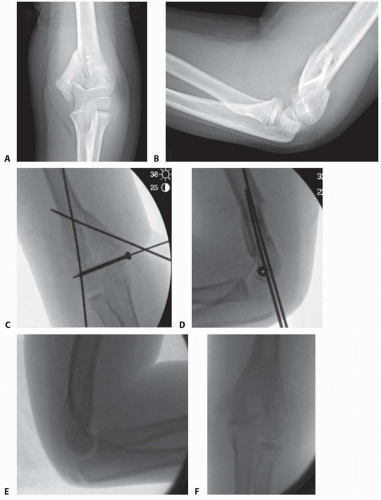

In younger children, an acceptable result can often be obtained with closed reduction and pinning, although this is generally not as straightforward as in a standard supracondylar humerus fracture (FIG 1).

Older children and young adolescents will often require an open approach.

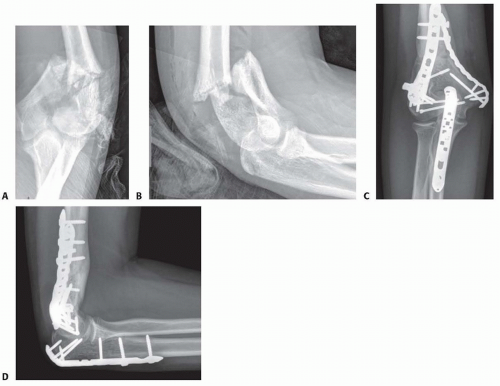

Comminution in the fossa may necessitate an olecranon osteotomy (FIG 2).

Generally, pediatric fractures are less comminuted than adult fractures and may not require a full osteotomy.

A Morrey slide approach is used in such a case where the triceps and ulnar periosteum are elevated off the ulna medially to expose the distal humerus without performing an osteotomy.3

It was originally described to avoid olecranon osteotomies in cases where total elbow replacement would be a salvage operation.

It can be useful in adolescents because the fractures are not as comminuted, but excellent visualization of the joint is desirable to provide anatomic reduction and restoration of elbow function.

ANATOMY

The distal humerus is a complex articulation.

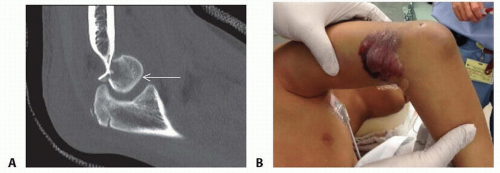

The ulnohumeral articulation is the articulation which needs to be reconstructed in this type of fracture. Occasionally, the radiocapitellar joint is also damaged with capitellar comminution (FIG 3A).

The remainder of the limb should be carefully examined. Coexisting wrist fractures can increase the risk of compartment syndrome and other soft tissue complications (FIG 3B).

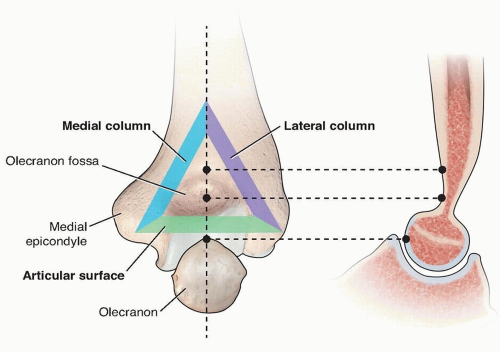

Conceptually, the distal humerus is a hinge which contains a medial and a lateral column connected by a middle hinge.

This creates a “triangle of stability,” which must be recreated in order for fixation to be successful in T-condylar humerus fractures.2 Regardless of the fixation strategy, this concept must be followed (FIG 4).

Posteromedially, the ulnar nerve travels through a groove in the distal humerus called the cubital tunnel. The nerve must be exposed along the medial border of the triceps down to the first motor branch, which pierces the flexor carpi ulnaris.

The triceps covers the distal humerus and attaches to the proximal ulna at the olecranon process.

The olecranon obscures the view of the distal humerus articular surface, with the elbow in extension.

To visualize the fracture line with the Morrey slide, the elbow must be flexed past 90 degrees.

Also important, the distal fracture fragments typically rotate with the apex anteriorly, which is important to remember when reducing the joint surface.

PATHOGENESIS

The mechanism of injury is a direct impact of the semilunar notch or coronoid process of the olecranon. Either of these structures can wedge into the trochlea, causing a split in the condyles.

This most frequently occurs with a fall of the flexed elbow.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of this fracture without anatomic restoration is characterized by stiffness, varus malunion, and chronic elbow dysfunction.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Mechanism of injury is important to obtain, higher energy injuries suggest an increased risk for compartment syndrome

A careful neurovascular examination should be performed, with particular attention to the median, ulnar, and radial nerves.

The limb should be inspected for open wounds. High-energy T-condylar fractures are often open injuries.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Quality anteroposterior (AP) internal and external oblique views can be useful if the diagnosis is in question.

Traction views can often be useful in fractures where shortening is present, although children and adolescents will often tolerate these poorly.

Computed tomography (CT) can be useful, but the coronal and sagittal reconstructions must be rendered in the plane of the joint or perpendicular to it (normal AP and lateral planes); otherwise, the information obtained will be difficult to interpret.

Coronal fragments may be missed if high-quality imaging is not obtained (see FIG 3A).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

T-condylar fractures must be differentiated from other fractures of the distal humerus in children and adolescents because the treatment will differ.

High-quality radiographs are generally sufficient to make this diagnosis.

A CT or traction views can be helpful if the diagnosis is in question or if a coronal shear fragment is suspected on plain radiographs.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Initial management includes a well-padded splint following adequate physical examination.

If the injury is open, an intravenous (IV) first-generation cephalosporin should be administered as soon as the injury is identified. If there is excessive contamination, comminution, or soft tissue injury, IV gentamicin is also recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree