Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Lisfranc Injury

Michael P. Clare

Roy W. Sanders

DEFINITION

A Lisfranc injury refers to bony or ligamentous compromise of the tarsometatarsal and intercuneiform joint complex and includes a spectrum of injuries ranging from a stable, partial sprain to a grossly displaced and unstable fracture or fracture-dislocation of the midfoot.

ANATOMY

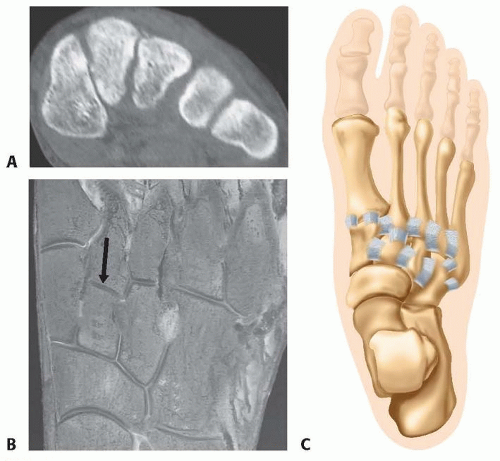

The bony elements of the medial three tarsometatarsal joints (medial, middle, and lateral cuneiforms and first, second, and third metatarsal bases) feature a unique trapezoidal shape in cross-section, creating a concave arrangement plantarly resembling a Roman arch (FIG 1A).

The second metatarsal is recessed between the medial and lateral cuneiforms in the axial plane and is positioned at the apex of the Roman arch in the coronal plane. It thus functions as the keystone of the entire midfoot complex (FIG 1B).

The tarsometatarsal joints are stabilized by dorsal and plantar tarsometatarsal ligaments.

Dorsal and plantar intermetatarsal ligaments provide further stability between the second through fifth metatarsal bases.

There are no intermetatarsal ligaments between the first and second metatarsals, which may predispose the area to injury.

The Lisfranc ligament courses from the plantar portion of the medial cuneiform to the base of the second metatarsal (FIG 1C).

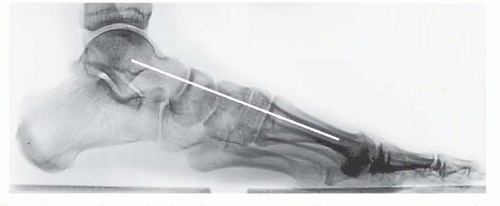

The unique bony arrangement of the medial midfoot imparts inherent bony stability to the medial and middle columns of the foot, which in combination with the stout plantar ligaments prevents plantar displacement of the metatarsal bases and facilitates the weight-bearing function of the first ray (FIG 2).

The medial three tarsometatarsal joints and the adjacent intercuneiform and naviculocuneiform articulations (medial and middle columns) have limited inherent motion, making these joints nonessential to normal foot function and therefore relatively expendable.

The medial column refers to the first tarsometatarsal and navicular-medial cuneiform articulations; the middle column includes the second and third tarsometatarsal joints and articulations between the navicular and middle and lateral cuneiforms, respectively.

The fourth and fifth tarsometatarsal (lateral column) joints have distinctly more inherent motion and are critical in accommodation of the foot to uneven surfaces.

These joints are considered essential joints to normal foot function and therefore nonexpendable.

PATHOGENESIS

Lisfranc injuries are generally the result of a high-energy injury, such as a fall from a height or a high-speed motor vehicle accident, but depending on the position of the foot, they may also result from a lower energy injury, such as a slip and ground-level fall.

These injuries result from a combination of axial load and dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, abduction, or adduction (or variable combinations thereof) of the midfoot.

FIG 2 • Normal weight-bearing lateral radiograph demonstrating normal alignment of the medial column and the weight-bearing first ray (white line).

The pathoanatomy is individually specific and highly variable and may consist of a pure ligamentous injury, a pure bony injury (fracture), or a combination.

Although the injury classically includes the first, second, and third tarsometatarsal joints, there may be involvement of all five tarsometatarsal articulations, extension into the intercuneiform joints, or even fracture lines into the navicular or cuboid proximally or metatarsal shafts or necks distally.

In pure ligamentous patterns, the stability of the injury depends on the status of the plantar tarsometatarsal ligaments. Disruption of these stout structures makes the injury unstable.

Partial injuries (sprains) occur as a result of lower energy and are more common with axial load and plantarflexion, such as in competitive sports.

In this instance, by definition, the plantar tarsometatarsal ligaments remain intact, making the injury stable.

NATURAL HISTORY

Stable injuries (partial sprains, extra-articular fractures) often require prolonged recovery time. When accurately diagnosed, however, patients with these injuries can generally expect full recovery and return to activity with minimal long-term implications.7

Unstable injuries that are misdiagnosed or inadequately treated generally go on to a poor result with persistent pain, activity limitations, and progressive posttraumatic arthritis in the involved joints,2, 3 necessitating arthrodesis as salvage.4, 9

A high index of suspicion must therefore be maintained; historically, up to 20% of unstable Lisfranc injuries are misdiagnosed on plain radiographs.3

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The physician should obtain a history of trauma and details of the exact injury mechanism (position of foot, direction of force, extent of energy involved).

The physician should observe any initial swelling and inability to bear weight.

A thorough examination of the involved foot and ankle also includes assessment of associated injuries and any other areas of swelling or tenderness to palpation.

The physician should observe the skin and soft tissue envelope. Diffuse swelling of the midfoot or plantar ecchymosis at the midfoot suggests a Lisfranc injury.

The physician should palpate the midfoot joints; pain at the midfoot with palpation suggests a Lisfranc injury.

The physician should test midfoot stability with passive flexion of the metatarsal heads and passive abduction and adduction through the forefoot. Pain at the tarsometatarsal joint region with passive forefoot range of motion suggests a Lisfranc injury.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

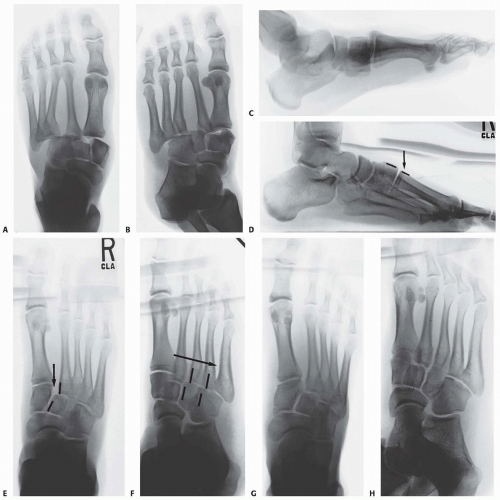

Initial radiographic evaluation consists of non-weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), oblique, and lateral views of the foot, which, depending on the extent of intra-articular displacement, may provide sufficient diagnostic information (FIG 3A-C).

Fluoroscopic stress views may be helpful in more subtle injuries; however, these studies are painful and generally require anesthesia.

We therefore prefer weight-bearing radiographs of the foot for more subtle injuries (FIG 3D-H); comparison weight-bearing radiographs of the contralateral foot may also be obtained where necessary.

The weight-bearing AP view of the foot will demonstrate intra-articular displacement through the first and second tarsometatarsal joints (so-called Lisfranc joint), intercuneiform joint, and naviculocuneiform joint; fractures through the first and second metatarsal bases, medial and middle cuneiforms, and proximal extension into the navicular; and the extent of columnar shortening or asymmetry.

The medial border of the second metatarsal should align with the medial border of the middle cuneiform (FIG 3D).

The oblique view will reveal intra-articular displacement through the third, fourth, and fifth tarsometatarsal joints and fractures of the third, fourth, and fifth metatarsal bases, lateral cuneiform, and cuboid.

The medial borders of the third and fourth metatarsals should align with the medial borders of the lateral cuneiform and cuboid, respectively (FIG 3E).

The lateral view may reveal dorsal-plantar displacement of fractures or dislocations as well as any flattening of the medial longitudinal arch, thereby reflecting the status of the weight-bearing medial column and first ray (FIG 3F).

Computed tomography (CT) scanning may also be beneficial in the instance of a subtle Lisfranc injury, particularly in a polytrauma patient or a patient with multiple extremity injuries that preclude weight-bearing radiographs, and in delineating proximal fracture line extension into the navicular, cuboid, or cuneiforms (FIG 4).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Partial Lisfranc injury (sprain)

Isolated metatarsal fracture

Navicular-cuneiform fracture

Anterior process of calcaneus fracture

Lateral ankle sprain

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment is indicated for partial Lisfranc injuries (sprains), which by definition are stable and therefore nondisplaced on weight-bearing radiographs.

Nonoperative treatment is also indicated for nondisplaced or minimally displaced extra-articular metatarsal base fractures with no intra-articular involvement (displacement) on weight-bearing radiographs.

Because of the often subtle nature of Lisfranc injuries and the negative consequences of misdiagnosis, if the findings are inconclusive, weight-bearing radiographs may be repeated 2 to 3 weeks after the injury.

Nonoperative management consists of immobilization in a venous compression stocking and prefabricated fracture boot.

The patient is allowed to bear weight to tolerance, and early progression to range of motion is encouraged.

The patient continues in the fracture boot for 5 to 6 weeks, at which point maintenance of alignment or radiographic union is confirmed on repeat weight-bearing radiographs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree