Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Glenoid Fractures

Thomas P. Goss

Travis C. Burns

Brett D. Owens

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

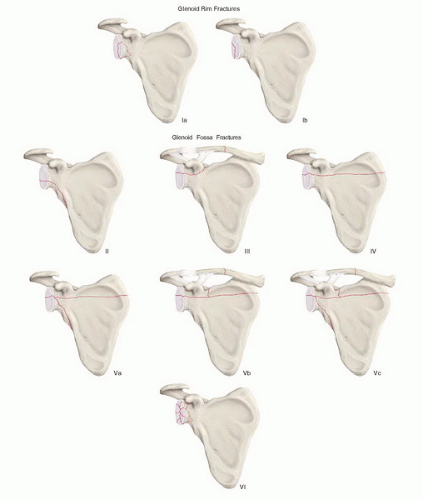

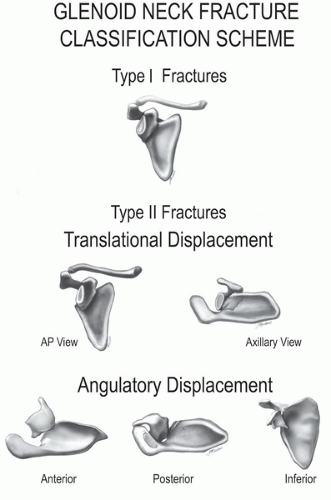

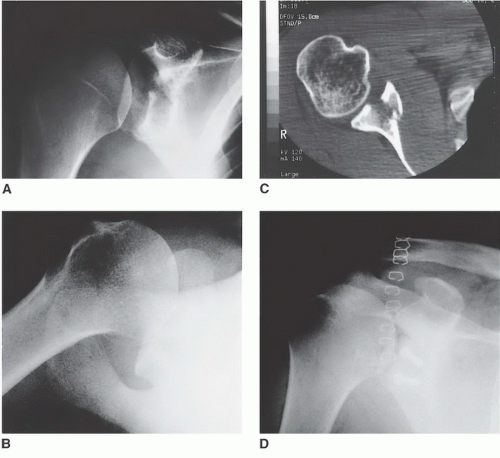

Fractures of the scapula comprise approximately 1% of all fractures. Because direct high-energy trauma is generally involved, there is a high incidence (80% to 95%) of associated osseous and soft-tissue injuries, which may be multiple and major and may threaten limb or life. Fractures of the glenoid process account for approximately one-third of scapular fractures and include disruptions of the glenoid cavity (the glenoid rim and the glenoid fossa; Fig. 33-1) and disruptions of the glenoid neck (Fig. 33-2). Although more than 90% of glenoid fractures are minimally displaced and can be treated nonoperatively, approximately 10% are significantly displaced and require surgical reconstruction. Fractures of the glenoid rim are managed surgically if the injury causes persistent subluxation of the humeral head or if the reduction is unstable. Instability can be anticipated if the fracture is displaced 10 mm or more and one-fourth or more of the glenoid cavity anteriorly or one-third or more of the glenoid cavity posteriorly is involved. Surgical indications for glenoid fossa fractures include (a) an articular step-off of 5 mm or more, (b) such severe separation of the fragments that a nonunion is likely, and (c) a fracture pattern that allows displacement of the humeral head out of the center of the glenoid cavity. Surgical treatment of glenoid neck fractures is considered if there is translational displacement of the glenoid fragment 1 cm or more or angular displacement of the fragment 40 degrees or more in either the coronal or axial plane (type II fractures) or both. Contraindications include severely comminuted fractures of the glenoid cavity and glenoid fractures in which comminution of the surrounding osseous structures precludes satisfactory fixation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Diagnosis is radiologic and begins with a “scapula trauma series,” composed of true anteroposterior and lateral views of the scapula and an axillary projection of the glenohumeral joint. Because of the complex bony anatomy in the area, however, a computed tomography scan is often required to accurately define these injuries and to allow optimal preoperative planning. Three-dimensional scanning with reconstruction can be extremely helpful to the orthopaedist trying to evaluate the most complex fracture patterns. These radiographs should also be reviewed carefully to identify associated fractures of the shoulder girdle including the remainder of the scapula, the clavicle, and the proximal humerus, as well as disruptions of the acromioclavicular, glenohumeral, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic articulations. Abrasions and open wounds involving the superficial soft tissues must be inspected carefully, and surgery may need to be delayed until they are adequately clean. Although vascular injury is quite uncommon, distal pulses should be palpated and if absent or questionable, arteriography should be performed. Injury to the brachial plexus also is uncommon, but a thorough neurologic examination is necessary to document function of the axillary, musculocutaneous, median, radial, and ulnar nerves. Electromyographic (EMG) testing can be performed 3 weeks after injury if a deficit is found or suspected. Scapulothoracic dissociation is a distinct clinical entity that should be considered. It has a very high incidence of neurovascular involvement and is characterized by (a) a history of violent trauma, (b) massive swelling of the shoulder girdle, and (c) posterolateral displacement of the scapula relative to the rib cage.

Should it be determined that surgical management for the glenoid fracture is necessary, a thorough knowledge of the shoulder anatomy is essential. Depending upon the clinical situation, the glenoid process may be approached from three directions (anterior, posterior, or superior). The specific type and location of the fracture is a prime determinant of the specific surgical approach. Frequently, combined approaches are used.

Basic orthopaedic and shoulder instruments should be available and fixation devices should include Kirschner wires (K-wires), 3.5- and 4.0-mm cannulated compression screws, and 3.5-mm malleable reconstruction plates. K-wires can be used for temporary or definitive fixation of glenoid fragments. The latter is the case when significantly displaced fracture fragments are too small to allow more substantial fixation, but one must be sure to bend the K-wire at its point of entry to avoid migration. The 3.5-mm malleable reconstruction plates are particularly helpful in the management of glenoid neck fractures. The 3.5- and 4.0-mm cannulated compression screws are especially useful in stabilizing fractures of the glenoid rim and the glenoid fossa. For patients with anterior rim, posterior rim, and type II glenoid cavity fractures, the iliac crest should be prepped and draped in case the fragment is comminuted, requiring placement of a tricortical graft to restore glenohumeral stability.

SURGERY

Although nerve block techniques are available, in most cases, general anesthesia is advisable because of (a) the awkward positioning that may be required, (b) the extensive dissection and manipulation that may be necessary, (c) the prolonged operative time that frequently occurs, and (d) the proximity of the patient’s head to the work being done. A regional block before the administration of general anesthesia, however, may be used for postoperative pain control.

The shoulder should be prepped and draped widely in case combined approaches or additional exposures are necessary.

Anterior Approach

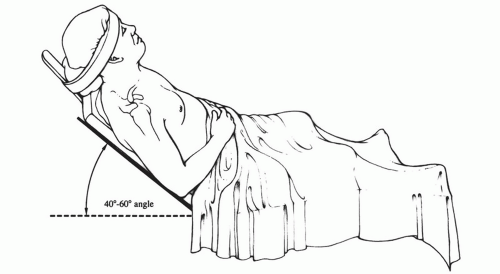

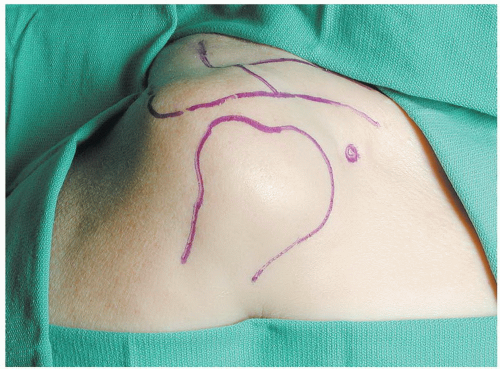

The patient is placed on the operating room table in the beach-chair position (Fig. 33-3). Bony landmarks are outlined with a marking pen (Fig. 33-4). An incision is made in Langer lines, centered over the glenohumeral joint and running from the superior to the inferior margin of the humeral head (Fig. 33-5). The deltoid muscle is exposed (Fig. 33-6) and split in the line of its fibers directly over the coracoid process (Fig. 33-7). The conjoined

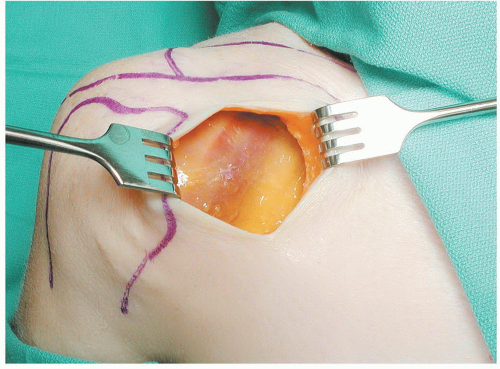

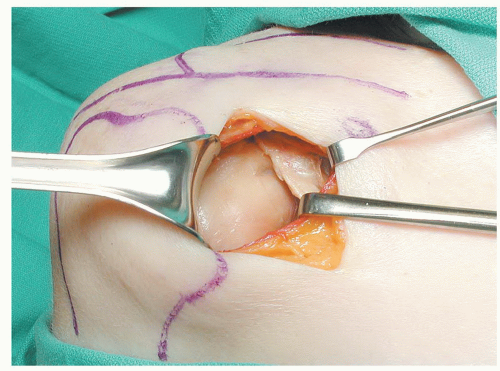

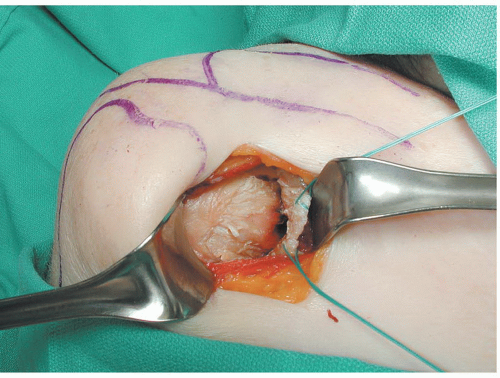

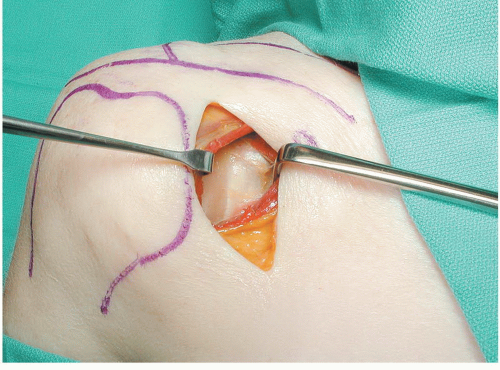

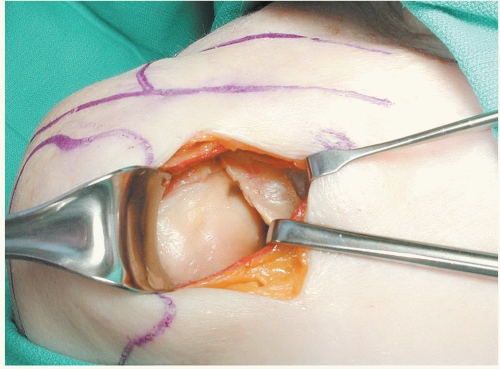

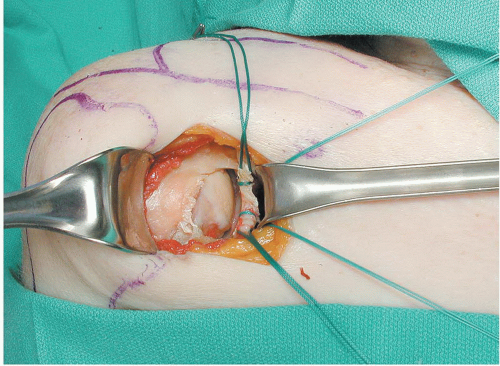

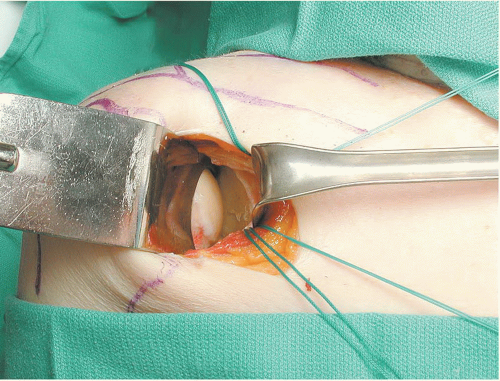

tendon and the pectoralis major muscle are retracted medially, while the deltoid muscle is retracted laterally. The arm is externally rotated onto a sterile arm support or positioner and the subacromial bursa is removed, exposing the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 33-8). (For fractures involving the superior aspect of the glenoid fossa, opening the rotator interval may allow sufficient exposure; Fig. 33-9.) The subscapularis tendon is incised 2.5 cm medial to the medial border of the bicipital groove and along its superior and inferior borders. It is then dissected off the underlying anterior glenohumeral capsule/glenoid neck periosteum and turned back medially (Fig. 33-10). The anterior glenohumeral capsule is incised in the same fashion and turned back medially (Fig. 33-11). With a humeral head retractor inserted into the glenohumeral joint (a Fukuda ring retractor is especially useful) and holding the humeral head out of the way, the entire glenoid cavity can be inspected and the surgeon has ready access to the anterior rim (Fig. 33-12). Support of the humerus, slight abduction, and slight external rotation of the humerus aid in relaxing the soft tissues and augment the anterior exposure. One must take care to avoid injury to the nearby axillary nerve.

tendon and the pectoralis major muscle are retracted medially, while the deltoid muscle is retracted laterally. The arm is externally rotated onto a sterile arm support or positioner and the subacromial bursa is removed, exposing the subscapularis tendon (Fig. 33-8). (For fractures involving the superior aspect of the glenoid fossa, opening the rotator interval may allow sufficient exposure; Fig. 33-9.) The subscapularis tendon is incised 2.5 cm medial to the medial border of the bicipital groove and along its superior and inferior borders. It is then dissected off the underlying anterior glenohumeral capsule/glenoid neck periosteum and turned back medially (Fig. 33-10). The anterior glenohumeral capsule is incised in the same fashion and turned back medially (Fig. 33-11). With a humeral head retractor inserted into the glenohumeral joint (a Fukuda ring retractor is especially useful) and holding the humeral head out of the way, the entire glenoid cavity can be inspected and the surgeon has ready access to the anterior rim (Fig. 33-12). Support of the humerus, slight abduction, and slight external rotation of the humerus aid in relaxing the soft tissues and augment the anterior exposure. One must take care to avoid injury to the nearby axillary nerve.

FIGURE 33-5 The standard anterior incision extending from the superior to the inferior margin of the humeral head, centered over the glenohumeral joint, and in Langer lines. |

FIGURE 33-7 The deltoid muscle is split in the line of its fibers directly over the palpable coracoid process and retracted medially and laterally. |

Figure 33-13 is an example of a case that required an anterior approach.

FIGURE 33-9 Drawing down on the arm allows one to see the rotator interval, which can be incised to gain access to the superior aspect of the glenoid process. |

FIGURE 33-11 The anterior glenohumeral joint capsule is incised similarly to the subscapularis tendon, tagged, and turned back medially. |

FIGURE 30-12 With the anterior glenohumeral joint capsule reflected medially and a humeral head retractor in place, ready access is available to the glenoid fossa and the anterior glenoid rim. |

Posterior Approach

The patient is placed on the operating room table in the lateral decubitus position—nonoperative side down (a towel roll placed in the axilla), operative side up, and the torso stabilized by a beanbag (Fig. 33-14). The upper extremity and shoulder complex are prepped and draped free; the elbow, forearm, and wrist/hand are encased in a sterile wrap; and a well-padded sterile-draped Mayo stand is prepared to serve as a mobile, adjustable armrest. Bony landmarks are outlined with a marking pen (Fig. 33-15). An incision is made over the lateral third of the scapular spine, along the posterior aspect of the acromion to its lateral tip and distally in the midlateral line for a distance of 2.5 cm (Fig. 33-16). Via sharp and blunt dissection deep to the subcutaneous layer, soft-tissue flaps are developed and retracted, exposing the posterior deltoid muscle (Fig. 33-17). The posterior deltoid is dissected sharply off the scapular spine and acromion and split in the line of its fibers for a distance of not more than 2.5 cm, starting at the lateral tip of the acromion. A blunt retractor such as a Darrach is helpful in identifying the deltoid-infraspinatus interval along the spine of the scapula. The posterior deltoid is bluntly separated off the underlying infraspinatus and teres minor musculotendinous units and retracted down to but not below the inferior margin of the teres minor (Fig. 33-18). The inferior half of the infraspinatus tendon is incised vertically 2 cm posterior to the greater tuberosity, and the infraspinatus/teres minor interval is opened. The infraspinatus can then be dissected off the underlying posterior glenohumeral joint capsule and retracted superiorly (Fig. 33-19). The posterior glenohumeral capsule is incised in the same fashion, separated subperiosteally off the posterior glenoid process, and retracted superiorly (Fig. 33-20). With a Fukuda retractor inserted into the joint and holding the humeral head out of the way, the entire glenoid cavity can be inspected and the surgeon has ready access to the posterior aspect of the glenoid process (Fig. 33-21). The entire infraspinatus tendon/posterior glenohumeral capsule can be detached laterally and superiorly and turned back medially for maximal exposure. With injuries that involve only the posteroinferior or inferior aspect of the glenoid cavity, one may be able to avoid detaching these structures completely—simply developing the infraspinatus/teres minor interval and making a linear incision in the capsule may allow adequate access. This is the so-called safe interval, safe because the infraspinatus is innervated by the suprascapular nerve from above, and the teres minor is innervated by the axillary nerve from below. The interval between the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles can be developed further, the underlying soft tissues elevated subperiosteally, and the long head of the triceps detached to gain access to the inferior aspect of the glenoid process and lateral border of the scapular body (Fig. 33-22). One must take particular care to protect and avoid injury to the nearby suprascapular and axillary nerves.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree