Fracture of the olecranon process is common, usually displaced, and nearly always treated operatively.

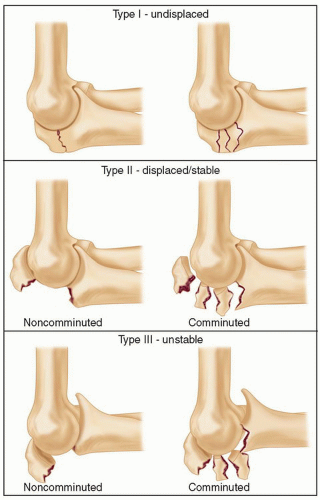

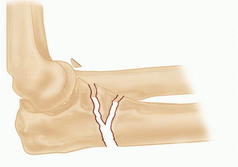

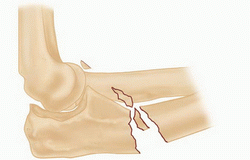

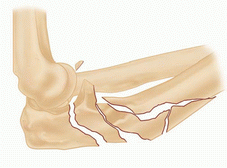

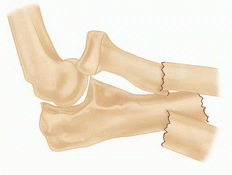

Important injury characteristics include displacement, comminution, and subluxation or dislocation of the elbow, and all are accounted for in the Mayo classification (FIG 1).6

Fracture-dislocations of the olecranon can be anterior (transolecranon) or posterior (the most proximal type of posterior Monteggia according to Jupiter and colleagues3) in direction.2,3,9,10

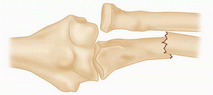

The eponym Monteggia is best applied to metaphyseal or diaphyseal proximal ulnar fracture associated with dislocation of the proximal radioulnar joint.

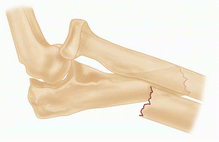

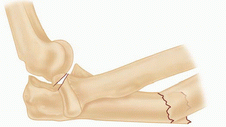

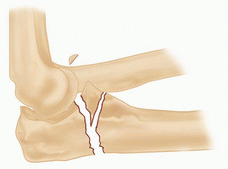

The Bado classification of Monteggia lesions with Jupiter subclassification of type II fractures is shown in Table 1.

Equivalent injuries in adults

Variable pathology that is felt to be equivalent to injuries classified by the Bado system

Equivalent injuries do not always fall within the traditional definition of a Monteggia fracture in that they do not always have a concomitant radiocapitellar dislocation. Therefore, it can be argued that these injuries are not necessarily equivalent to Monteggia fractures.

Type I and type II injuries are the only ones that have equivalent injury patterns.

The greater sigmoid notch of the ulna is formed by the coronoid and olecranon processes and forms a nearly 180-degree arc capturing the trochlea.

The region between the coronoid and olecranon articular facets is the nonarticular transverse groove of the olecranon, a common location of fracture and a place where precise articular reduction is not critical.

The triceps has a broad and thick insertion from just superior to the point of the olecranon and the tip of the olecranon process that can be used to enhance fixation of small, osteoporotic, or fragmented fractures and can be split longitudinally, if needed, when applying a plate.

The radioulnar articulation is stabilized by the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) at the distal radioulnar joint, the interosseous ligament in the midforearm, and the annular ligament at the proximal radioulnar joint (PRUJ). Fracture of the ulna with dislocation of the PRUJ disrupts the annular ligament, but typically, the other structures are spared.

In a true Monteggia lesion (fracture-dislocation) of the forearm, the radial head dislocates anterolaterally from the PRUJ.

Fractures of the olecranon and proximal ulna can result from a direct blow to the point of the elbow or indirect forces during a fall on the outstretched hand.

Stable nondisplaced or minimally displaced olecranon fractures are uncommon. The majority of olecranon fractures are displaced and benefit from operative treatment.

The occasional untreated displaced simple olecranon fracture demonstrates a slight flexion contracture, some weakness of extension, no arthrosis, and little, if any, pain.

Table 1 Bado Classification of Monteggia Lesions with Jupiter Subclassification of Type II Fractures

Type

Description

Illustration

I

Anterior dislocation of the radial head with fracture of the diaphysis of the ulna with anterior angulation of the ulnar fracture (most common type of lesion)

II

Posterior or posterolateral dislocation of the radial head with fracture of the ulnar diaphysis with posterior angulation of the ulnar fracture

IIA

Fracture at the level of the trochlear notch (ulnar fracture involves the distal part of the olecranon and coronoid)

IIB

Ulnar fracture is at the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction, distal to the coronoid.

IIC

Ulnar fracture is diaphyseal.

IID

Comminuted fractures involving more than one region

III

Lateral or anterolateral dislocation of the radial head with fracture of the ulnar metaphysis

IV

Anterior dislocation of the radial head with a fracture of the proximal third of the radius and ulna at the same level

Adapted from Bado J. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967;50:717; Jupiter JB, Leibovic SJ, Ribbans W, et al. The posterior Monteggia lesion. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5:395-402.

In contrast, undertreated or poorly treated fracture-dislocations of the olecranon often lead to severe arthrosis and angulation of the arm under the influence of gravity.

Even well-treated complex injuries are at risk for stiffness, heterotopic ossification, arthrosis, and occasionally nonunion.

Knowledge of the characteristics of the patient (age, sex, medical health) and the injury (mechanism, energy) will help the surgeon understand the injury and determine optimal treatment.

First, the patient is assessed for life-threatening injuries (Advanced Trauma Life Support [ATLS] protocol) and any medical problems that may have contributed to the injury.

A secondary survey is performed to identify any other fractures, ipsilateral arm injuries in particular.

The skin is inspected for any wounds associated with the fracture.

The pulses are palpated, capillary refill inspected, and an Allen test performed if necessary.

Peripheral nerve function is assessed.

Patients with high-energy injuries, particularly those with ipsilateral wrist or forearm injuries, are at risk for compartment syndrome. If the clinical examination is suggestive or unreliable (owing to problems with mental status), compartment pressure monitoring should be performed.

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs are used for initial characterization of the injury.

Radiographs after reduction or splinting or oblique views can be useful.

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for characterization of fracture-dislocations. In particular, three-dimensional (3-D) CT reconstructions can be useful for assessment of the coronoid and radial head.

Elbow dislocation

Essex-Lopresti fracture-dislocation of the forearm (disruption of the interosseous ligament and or TFCC usually with fracture of the radial head)

Fracture-dislocations of the elbow (“terrible triad” injury)

Distal humerus fracture

Nonoperative management is appropriate for the rare fracture of the olecranon that is less than 2 mm displaced with the elbow flexed 90 degrees.

Four weeks of splint immobilization followed by active-assisted mobilization of the elbow will usually result in a healed fracture and good elbow function.

The vast majority of olecranon fractures are displaced and merit operative treatment.

Transverse, noncomminuted fractures not associated with fracture-dislocation are treated with tension band wiring.4,8

Comminuted fractures and fracture-dislocations are treated with dorsal contoured plate and screw fixation.1,2,3

The treatment of fracture-dislocations requires attention to the coronoid, radial head, and lateral collateral ligament.2,9,10,11

Fracture-dislocations of the forearm (anterolateral Monteggia injuries) is treated with anatomic realignment of the ulna and plate and screw fixation.10 Inadequate radiocapitellar alignment suggests residual ulnar angulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree