Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Clavicular Fractures and Nonunions

Daniel B. Chan

Peter Kloen

David L. Helfet

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Clavicular fractures are relatively common and comprise approximately 35% (1) of fractures seen in the shoulder or approximately 4% (2) of all fractures seen in adults. Midshaft fractures account for a majority (69%) of clavicle fractures, with lateral-sided fractures comprising most of the remainder and medial-sided fractures being a relatively rare entity. Traditionally, midshaft fractures have been treated nonoperatively with the assumption that most fractures heal without any significant functional deficit or deformity. However, a recent study by McKee et al. (3) showed objective clinical deficits in displaced midshaft fractures treated nonoperatively. Specifically, strength and endurance for flexion, abduction, external, and internal rotation were all significantly decreased compared to the uninjured side (67% to 85% of normal). When comparing displaced midshaft clavicle fractures

treated conservatively to those treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial found several advantages for operative treatment (4). Specifically, those fractures treated with surgery had a quicker time to radiographic union, fewer nonunions, and fewer symptomatic malunions and were more satisfying at 1-year follow-up with both the appearance and general function of the shoulder. The most common complication associated with surgery was irritation associated with the hardware.

treated conservatively to those treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), a prospective, multicenter randomized clinical trial found several advantages for operative treatment (4). Specifically, those fractures treated with surgery had a quicker time to radiographic union, fewer nonunions, and fewer symptomatic malunions and were more satisfying at 1-year follow-up with both the appearance and general function of the shoulder. The most common complication associated with surgery was irritation associated with the hardware.

Defining the parameters of a “displaced” midshaft clavicle fracture remains a topic of considerable debate, but a study by Robinson et al. (5) found that the risk of nonunion was significantly increased by advanced age, female gender, complete displacement (no cortical apposition), and the presence of comminution. In addition, the previously mentioned Canadian studies have suggested symptomatic malunion to be more common in fractures where shortening is greater than 2 cm (3). These symptoms can vary from a mild ache during overhead activities to severe and disabling resting pain. The typical displacement pattern includes shortening of the lateral fragment and proximal displacement of the medial fragment, due in part from the weight of the arm on the lateral fragment and in part from the pull of the sternocleidomastoid on the medial fragment. In addition to traditional indications for operative fixation of clavicle fractures including open fracture or impending open fracture, neurovascular compromise, polytrauma, and occasionally cosmesis, the senior author routinely offers operative treatment for midshaft clavicle fractures to patients with 100% displacement, extensive comminution, and shortening greater than 2 cm, or for highly active/athletic patients. Neurovascular symptoms can manifest themselves from mild dysesthesias or paresthesias to a full-blown thoracic outlet syndrome with a decreased peripheral pulse and/or venous congestion. The second group of patients who are candidates for operative intervention are those patients who present with a painful clavicular nonunion.

The incidence of midshaft clavicular nonunions is relatively low. A recent systematic review of 2,144 midshaft clavicle fractures showed that nonoperative treatment of 1,145 fractures resulted in a nonunion rate of 5.9% (6). Nonunion rates for lateral clavicle fractures are reportedly higher (22% to 30%) (7, 8). Several known factors predispose to the development of a clavicular nonunion: open fracture, segmental comminution, displacement, initial shortening greater than 2 cm, insufficient length of immobilization, operative treatment, and refracture. The pain complaints can vary from a mild ache during overhead activities to severe and disabling resting pain. Once the patient and physician are convinced that the nonunion is the source of the symptoms, there are essentially no contraindications to surgery other than compromised medical conditions that may place the patient at risk for anesthesia. Aesthetic reasons are a relative contraindication given the unpredictability of the unsightly bump and/or scar formation.

Many techniques have been suggested for surgical treatment of fractures and nonunions of the clavicle, but ORIF with plates and screws remain the most common treatment modality with intramedullary fixation less commonly used. Good clinical and radiographic results have been achieved with intramedullary devices, and this method has the potential of being minimally invasive, but obtaining a closed reduction in highly displaced or comminuted fractures to allow the passage of a flexible titanium nail or a cannulated screw can be technically demanding. In addition, hardware removal is often required and studies have shown that plate fixation offers a biomechanically superior construct (9).

With respect to traditional ORIF, placement of the plate on the superior surface of the clavicle has been the long-standing construct of choice. While this construct theoretically has biomechanical advantages in buttressing fractures with inferior comminution (10), hardware prominence requiring subsequent plate removal and neurovascular injury from a superior to inferior drilling trajectory remain concerns. Current implants commonly used in this location include 3.5-mm reconstruction plates or DC-type plates that may be precontoured and may offer locking screw options. Alternatively, an anteroinferior approach to plating of midshaft clavicular fractures was developed to avoid this complication and has been found to be successful in clinical series (11, 12, 13, 14, 15). In addition, lateral fixation is theoretically enhanced with an anteroinferior plate as the clavicle has a greater anterior- posterior dimension than superior-inferior laterally, allowing screws greater than 22 mm to be placed. Hardware prominence is less problematic as the deltoid and clavicular head of the pectoralis major provide adequate softtissue coverage. Finally, with the typical displacement pattern described above, a superiorly placed plate relies solely on the pullout strength of the lateral screws to prevent the entire construct from lifting off the lateral fragment. An anteroinferior plate places fixation perpendicular to the plane of displacement, theoretically affording increased stability. Biomechanical data comparing the two plating methods remain mixed, with some studies suggesting superior plating to be a stronger construct (16), whereas a recent study by the senior author showed an advantage to anteroinferior plating with respect to bending rigidity and comparable axial and torsional stiffness (17). Most clinical studies have been performed with nonlocking plates although numerous manufacturers currently offer precontoured locking plates for both superior and anteroinferior placement, which theoretically offer improved fixation in short segments (i.e., lateral fractures) or in osteoporotic bone. However, these benefits over standard nonlocking plates have yet to be demonstrated clinically. The use of precontoured plates can theoretically reduce operating room time when compared to bending traditional reconstruction plates, but one study showed that 38% of the time, these implants had a poor fit on individual clavicular anatomy especially in the lateral third of the clavicle, where the “S” curve of the clavicle is most pronounced on the superior surface (18).

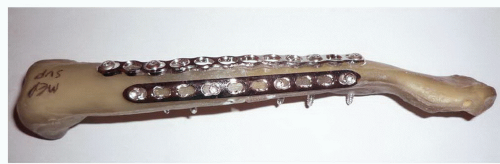

Based on the theoretical advantages of both plating locations and the incidence of hardware irritation associated with traditional 3.5-mm implants, the senior author has been performing fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures with a dual-plating construct using minifragment implants for the past several years. Typically,

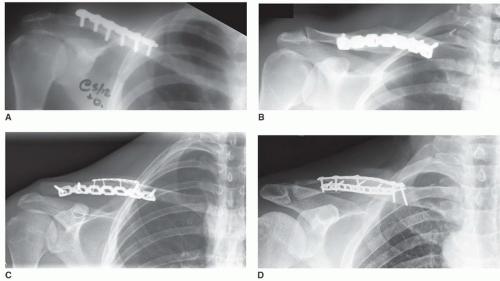

a 2.7-mm reconstruction plate (Synthes, Paoli, PA) is placed superiorly to allow for intraoperative contouring to the clavicular “S” curve and a 2.4-mm locking compression plate (LCP) (Synthes, Paoli, PA) is placed anteroinferiorly. An LCP is used in this location as it affords better resistance to bending in the superior-inferior plane and the clavicle is relatively straight in this location. The use of two plates allows a 90-90 construct that can effectively buttress comminution in both planes and the plates can act as washers for lag screws in both planes. In addition, the thickness and dimensions of the 2.7-/2.4-mm plates are significantly less than traditional 3.5-mm implants previously used. In the senior author’s experience, no patient undergoing surgical fixation of a displaced midshaft clavicular fracture using this technique has experienced hardware irritation that subsequently required removal. Unpublished biomechanical data comparing this construct to constructs tested in the study mentioned above by the senior author have shown that the minifragment dual plating construct is comparably strong to 3.5-mm implants placed on the superior or anteroinferior surface. Figures 29-1 and 29-2 show the appearance of the construct in a biomechanical model used for testing. The plates typically used have locking hole options although the vast majority of cases done by the senior author have used nonlocking screws only. Figure 29-3 shows the evolution of midshaft clavicle fixation constructs over time. Traditionally, a 3.5-mm reconstruction plate was contoured to the superior surface of the clavicle (Fig. 29-3A). However, because of problems with hardware prominence, anteroinferior plating using the same reconstruction plate was subsequently advocated with the advantage of longer screws possible in the distal clavicle (Fig. 29-3B). Despite this, some fracture patterns feature a superior

segment of comminution that can be stabilized with a supplemental minifragment plate (Fig. 29-3C). Our institution’s current construct of choice (Fig. 29-3D) now features minifragment plates on both the superior and anteroinferior surfaces to maximize fragment buttressing and screw trajectories while minimizing hardware irritation.

a 2.7-mm reconstruction plate (Synthes, Paoli, PA) is placed superiorly to allow for intraoperative contouring to the clavicular “S” curve and a 2.4-mm locking compression plate (LCP) (Synthes, Paoli, PA) is placed anteroinferiorly. An LCP is used in this location as it affords better resistance to bending in the superior-inferior plane and the clavicle is relatively straight in this location. The use of two plates allows a 90-90 construct that can effectively buttress comminution in both planes and the plates can act as washers for lag screws in both planes. In addition, the thickness and dimensions of the 2.7-/2.4-mm plates are significantly less than traditional 3.5-mm implants previously used. In the senior author’s experience, no patient undergoing surgical fixation of a displaced midshaft clavicular fracture using this technique has experienced hardware irritation that subsequently required removal. Unpublished biomechanical data comparing this construct to constructs tested in the study mentioned above by the senior author have shown that the minifragment dual plating construct is comparably strong to 3.5-mm implants placed on the superior or anteroinferior surface. Figures 29-1 and 29-2 show the appearance of the construct in a biomechanical model used for testing. The plates typically used have locking hole options although the vast majority of cases done by the senior author have used nonlocking screws only. Figure 29-3 shows the evolution of midshaft clavicle fixation constructs over time. Traditionally, a 3.5-mm reconstruction plate was contoured to the superior surface of the clavicle (Fig. 29-3A). However, because of problems with hardware prominence, anteroinferior plating using the same reconstruction plate was subsequently advocated with the advantage of longer screws possible in the distal clavicle (Fig. 29-3B). Despite this, some fracture patterns feature a superior

segment of comminution that can be stabilized with a supplemental minifragment plate (Fig. 29-3C). Our institution’s current construct of choice (Fig. 29-3D) now features minifragment plates on both the superior and anteroinferior surfaces to maximize fragment buttressing and screw trajectories while minimizing hardware irritation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A thorough history and physical examination are mandatory in the operative treatment of clavicular fractures, especially in the case of a nonunion. Preoperative functional status, mechanism of injury, associated injuries, and medical comorbidities all influence surgical decision making. For the nonunion patient, the amount of pain and/or functional disability should be documented. Laboratory studies including CBC, CRP, and ESR may be considered if infection is in the differential as a cause for nonunion. A thorough neurovascular examination is of paramount importance especially in the acute fracture to rule out vascular compromise or injury to the brachial plexus. Although an associated pneumothorax or hemothorax is rare in these injuries, they remain a possibility—as such, complete evaluation should include auscultation for equal breath sounds.

Plain radiographs often provide adequate information for midshaft fractures and nonunions. In addition to the standard anteroposterior view from the clavicle that visualizes the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular (AC) joints, a 45-degree cephalad view (“serendipity” view) is helpful. In the former view, the upper lung fields should be evaluated to rule out a pneumothorax. The latter view eliminates the underlying thoracic structures. The amount of shortening and displacement should be measured. The cortical contours and thickness should be traced to assess for any rotational deformity. It is important, especially in the patient with a possible neurovascular deficit, to rule out scapulothoracic dissociation. This requires obtaining a chest radiograph to compare the offset or lateral displacement of both scapulae. While 3-D CT scan offers little additional information in the acute fracture setting, it can be helpful in the nonunion setting to identify areas of bone bridging or deficiency. Shortening can also be determined more precisely when both sides are included. Three-dimensional CT scans can also better delineate lateral and medial injuries and their relationship to articular surfaces. The following illustrative case in this example is that of a 50-year-old business executive who sustained a midshaft clavicle fracture after a fall from a bicycle. The initial radiographs show approximately 50% displacement and 1 cm of shortening (Fig. 29-4), but the patient was highly intolerant of sling treatment with significant pain and disability that was interfering with his daily responsibilities. As such, operative treatment was offered in order to allow him to function without the need for immobilization and to facilitate a quicker recovery.

SURGERY

The patient is placed on the operating table in a beach-chair position. Many operating room tables are available for this purpose, but traditional “shoulder tables” are designed more for arthroscopy and arthroplasty and as such do not allow for easy fluoroscopic imaging. We prefer to use a standard radiolucent table with a leg extension turned backward such that the head is resting at the end of the foot extension. The table is then flexed to the appropriate beach-chair position. A foam head-holder along with an elastic bandage is used to secure the head, although commercial head-holding devices also exist. This setup allows unimpeded access for the fluoroscopy unit to enter from behind the patient (Fig. 29-5). We typically flip the fluoroscopic machine such that the emitter is in front of and the detector behind the patient. This is done to allow adequate tilting of the machine to obtain orthogonal views of the clavicle intraoperatively (Fig. 29-6). In this case, a preincision fluoroscopic view shows more displacement in the beach-chair position than the supine office radiograph, although this is slightly unusual in that the lateral fragment is more superiorly displaced (Fig. 29-7).

Most often, general endotracheal anesthesia is used, although we have successfully performed the procedure using regional (interscalene) block and sedation in many cases. To facilitate draping and to expand the operative field, the endotracheal tube is positioned out the opposite corner of the mouth. A rolled up towel is placed between the scapula to make the clavicle more prominent and to facilitate draping of the posterior shoulder. For nonunion surgery, the ipsilateral iliac crest may be prepped as well although we have gone to using more bone graft substitutes and less autogenous graft. Prior to performing the surgical prep, the surgical field is isolated using a plastic barrier drape. It is imperative to include the sternoclavicular joint in the surgical field. We prefer to use a completely occlusive draping technique (Fig. 29-8) with a stockinette covering the hand and forearm as well as an Ioban (3M, St Paul, MN) dressing covering the axilla and operative field to decrease the risk of surgical site infection from commonly encountered Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes species.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree