Open Management of the Stiff Shoulder

Thomas M. Lawrence

Scott P. Steinmann

INTRODUCTION

Arthroscopic capsular release is a reliable treatment option in patients with shoulder stiffness with many advantages over open surgery.1,2,22,17 The relative indications for open surgical release have therefore decreased and open release is now rarely performed in the treatment of idiopathic frozen shoulder.15 The main indication for an open surgical release is significant extra-articular adhesions or contracture that cannot be completely managed by closed manipulation or arthroscopic release.26

Patients who have developed posttraumatic or postsurgical shoulder stiffness may form extensive extra-articular adhesions involving subscapularis. In this setting, open surgery is required to release adhesions outside the joint and manage the subscapularis contracture which cannot be performed with arthroscopy. The classic case is the patient who has severe loss of external rotation (ER) following a history of an open instability repair that used a subscapularis shortening procedure such as a Putti-Platt. Such a patient is at risk for development of arthritis due to excessive joint compressive force that is directed across the posterior joint as a result of the anterior soft-tissue and may respond favorably to open release.18 Other indications for open release are if the patient has motion loss following fracture fixation with associated hardware or after shoulder arthroplasty. Furthermore, open release may be more appropriate for stiffness secondary to surgery around the capsule which has produced dense scar tissue around the region of the axillary nerve.

The major benefit of open release is that it allows accurate location and release of contracted structures both intraarticularly and extra-articularly under direct vision. The major disadvantages of an open release are postoperative pain, which can interfere with initiating early motion, and the necessity to limit ER in an effort to protect the subscapularis repair. Although the use of open release is currently limited, it is important to appreciate in which situation this procedure may be required, and to have a thorough understanding of the technical surgical principles, many of which have an application outside of the treatment of the stiff shoulder.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The aim of the procedure is to release adhesions and contracted tissues to increase the range of motion, while maintaining glenohumeral stability. It is critical to identify tissues that are contracted and determine how and to what extent their release will increase range of motion. The release should initially address the extra-articular adhesions in the subacromial, subdeltoid, and subcoracoid spaces. Once this is complete, intra-articular release includes the coracohumeral ligament (CHL) and rotator interval (RI), the subscapularis, and the capsule.

It is preferable to perform this procedure under interscalene regional block, in addition to general anesthesia, so that passive range of motion therapy can be started immediately after surgery. The patient is positioned in the beach chair position with the waist at 45 degrees and knees at 30 degrees. Perform an examination under anesthesia to determine degree of flexion, abduction, and external and internal rotation with the arm at the side, as well as in abduction. The restriction in motion can direct the surgeon to the releases required.

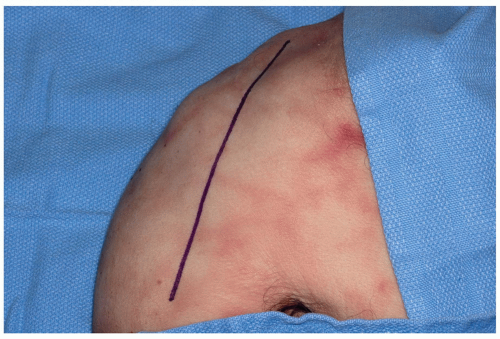

Following standard skin preparation and sterile draping, the incision begins at the anterior portion of the clavicle, passes approximately 1 cm lateral to the coracoid, and intersects the arm at the junction of the medial 40% and lateral 60% (Fig. 11-1). The deltopectoral interval is identified, which in revision surgery may be difficult due to scarring. The dissection begins proximally at the level of the clavicle, leaving the cephalic vein in its bed medially, cauterizing the lateral branches to the deltoid. The superior 1 to 2 cm of pectoralis major insertion should be released to facilitate exposure. The clavipectoral fascia lateral to the conjoint tendon (coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps) is then incised,

and the interval between the conjoint tendon and subscapularis is identified. Develop the subcoracoid space and retract the conjoint tendon medially taking care not to injure the musculocutaneous nerve11 and brachial plexus.20

and the interval between the conjoint tendon and subscapularis is identified. Develop the subcoracoid space and retract the conjoint tendon medially taking care not to injure the musculocutaneous nerve11 and brachial plexus.20

Next release the subacromial and subdeltoid spaces with a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. Flexion and rotation of the arm further exposes this tissue plane and allows proximal dissection up into the subacromial space. After the rotator cuff is identified, hypertrophic bursa and scar are excised. To complete and confirm the subdeltoid release, use an index finger to sweep superiorly, posteriorly, laterally, and finally anteriorly. At this point the deltoid should be fully separated and mobile from the rotator cuff and the underlying proximal humerus down to the level of the deltoid insertion. This will allow easy insertion of retractors to expose the subscapularis and RI.

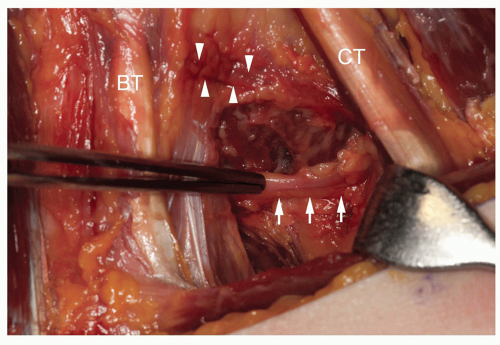

Identification and protection of the axillary nerve is necessary throughout the procedure (Fig. 11-2). The nerve is found at the inferior border of the subscapularis in the subcoracoid space, although identification may be difficult in cases of severe scarring. The “tug test”10 can be useful to facilitate identification of the axillary nerve; this is performed by placing a finger from one hand on the nerve as it passes inferior to subscapularis and a finger from the other hand under the deltoid on the anterior branch of the nerve. The application of gentle pressure from one end will allow the transmission to be felt at the other end confirming the location of the nerve, as well as demonstrating undersurface release of the deltoid. Location of the axillary nerve also serves as a guide for the lower subscapular nerve which is found posterior or just lateral to the axillary nerve. Dissection along the anterior surface of the subscapularis should therefore remain lateral to the axillary nerve to avoid subscapularis denervation.16,27

After complete extra-articular mobilization, the RI is identified and opened. The coracoacromial ligament overhangs the RI and therefore excision may improve exposure (Fig. 11-3). The RI boundaries (Fig. 11-4) are the subscapularis inferiorly, supraspinatus superiorly, and coracoid medially.12 Release and excise the contents of the interval which include the coracohumeral and superior glenohumeral ligaments and anterior joint

capsule (Fig. 11-5). Release of the CHL will help restore ER and assist in the mobilization of the subscapularis.21 The long head of biceps should be examined and if diseased or scarred within the joint, then tenotomy and tenodesis are performed.

capsule (Fig. 11-5). Release of the CHL will help restore ER and assist in the mobilization of the subscapularis.21 The long head of biceps should be examined and if diseased or scarred within the joint, then tenotomy and tenodesis are performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree