Abstract

Introduction

Cancer patients are living longer with deficiencies and functional impairments requiring often typically a care in physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR).

Objective

To examine the care of cancer patients in PMR.

Method

Investigation made with a questionnaire diffused from the e-mail listing of the Société Française de Médecine Physique et de Réadaptation .

Results

Sixty-seven answers received. Fifty-seven centers take care of cancer patients. On average, 4% of cancer patients are hospitalised in PMR. Spinal cord injuries and hemiplegias are the most common impairments. Forty-two percent of the PMR units take the patients in all the stages of cancer treatment. Working relationships between PMR and oncology units are formalized only eight times out of 52. In case of health degradation, relationships with a palliative care unit are frequent but not generalized. Eighty-five percent of the centers think that PMR is not enough developed in oncology.

Conclusions

In spite of its limited character, this investigation shows that the PMR units take these patients. Situations where PMR has an important role in the follow-up of cancer patients are multiple and publications have showed its interest, especially on the limitations of activities. It is important to make better known the interest of PMR in oncology units but also to develop specific care within PMR units.

Résumé

Introduction

Les patients cancéreux vivent de plus en plus longtemps avec des déficiences et des retentissements fonctionnels relevant souvent typiquement d’une prise en charge en médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR).

Objectif

Faire un état des lieux de la prise en charge des patients cancéreux en MPR.

Méthode

Enquête réalisée avec un questionnaire diffusé à partir du listing mail de la Société française de médecine physique et de réadaptation.

Résultats

Soixante-sept réponses reçues. Cinquante-sept centres prennent en charge des patients cancéreux. En moyenne, 4 % de patients cancéreux hospitalisés en MPR. Les lésions médullaires et hémiplégies arrivent au premier rang. Quarante-deux pour cent des services prennent les patients à toutes les phases du traitement anticancéreux. Les liens entre les services de MPR et d’oncologie ne sont formalisés que huit fois sur 52. En cas d’aggravation clinique, les relations avec une unité mobile de soins palliatifs sont fréquentes mais pas généralisées. Quatre-vingt cinq pour cent des centres pensent que la MPR n’est pas assez développée en cancérologie.

Conclusions

Malgré son caractère limité, cette enquête montre que les services de MPR prennent en charge ces patients. Les situations où la MPR a un rôle important dans le suivi des patients cancéreux sont multiples et des publications ont montré son intérêt en particulier, sur les limitations d’activités. Il est important de mieux faire connaître l’intérêt de la MPR au sein des services de cancérologie mais aussi de développer des prises en charge spécifiques au sein des services de MPR.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Cancers are the first cause of death in France and their incidence is important. The International Agency for Research one Cancer (IARC) considers that there were 270 000 new cases in France in 2005. The earlier detection with screenings and the progress of treatments increase the life expectancy of cancer patients. However, the care of these patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation (PMR) remains still difficult even if the contribution of PMR is underlined in the publications of the last two decades . Multiple factors could certainly explain these difficulties: fragility of the patients, fear of complications or end of life for the physiatrist; ignorance of the contribution of the PMR for the oncologist. However, many clinical demonstrations of cancers cause deficiencies requiring typically a care in PMR.

To bring elements of reflection in this domain, we made an investigation with the centres of PMR. The aim of this investigation was to know if they take care of cancer patients and how is organized this care.

1.2

Method

The investigation was realized in 2006. A questionnaire was diffused by e-mail to the physiatrists from the mail listing of the “Société Française de Médecine Physique et de Réadaptation” (SOFMER), which included approximately 650 addresses at the time of the sending.

A single sending realized in April and May 2006 was made.

The questionnaire contained three parts:

- •

the first part addressed the centres which take care of cancer patients; the questions concerned:

- ∘

the number of beds of hospitalization (adults, children, complete hospitalization or day hospitalization);

- ∘

the number of cancer patients a year and the total number of patients taken care in 2004 and in 2005, without distinguishing adults/children;

- ∘

the deficiencies and the taken care pathologies;

- ∘

the phase of evolution of the cancer;

- ∘

the possible sanitary resorts in case of health degradation;

- •

the second part addressed the services which told not to take care of cancer patients; the questions concerned the reasons why they did not take care of cancer patients;

- •

the third part addressed all the centres; the questions concerned the place of PMR in oncology and on the needed improvements for the care of cancer patients in PMR.

1.3

Results

Sixty-seven answers were received. The answers come from centres of all regions of France, and from seven centres abroad (3 in Switzerland, 2 in Tunisia, 1 in Belgium and 1 in Greece).

Fifty-seven centres take care of cancer patients.

1.3.1

Results of the questionnaires of the 57 centres taking care of cancer patients

1.3.1.1

Type of hospitalization and number of beds

Forty-eight centres take care only of adults, six only of children, and three of adults and children.

The number of beds of adults complete hospitalization is from eight to 800 by centre (average: 78; median: 50). For children, the number is from eight to 70 (average: 30). Thirty-six centres have places of day hospitalization for adults; the number of places is from two to 80 (average: 18; median: 8). Eight services have places of day hospitalization for children; the number of places is from two to 80 (average: 21; median: 12).

The distribution in complete hospitalization and in-day hospitalization is reported in Table 1 .

| Adults | Children | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | HJ | HC | HJ | |

| Number | 51 | 36 | 9 | 8 |

1.3.1.2

Patients percentage taken care a year

Thirty-five answers were exploitable in 2004 and 40 in 2005 ( Table 2 ). Figures are comparable between 2004 and 2005 and show important differences between the centres.

| % cancer patients/year 2004 | % cancer patients/year 2005 | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 0,5 | 0,4 |

| Maximum | 38,3 | 37,9 |

| Median | 1,8 | 2 |

| Average | 4 | 4,2 |

1.3.1.3

Types of deficiencies and taken care pathologiesf

Types of deficiencies and taken care cancerous pathologies are in Table 3 . Spinal cord injuries and hemiplegias are the most common impairments. A little more than 40% of the centre take care of patients for an amputation. We can wonder of this percentage. It is necessary to notice that it is the percentage of centres and not the percentage of patients. In the column “others” of this question, 10 answers (out of 23) were clarified and correspond to breast cancers with lymphoedema (4), bone primitive cancers (2), gastrointestinal cancers (3) and one blood-related neoplasm.

| Yes | % of units | |

|---|---|---|

| Spinal cord compression (paraplegia) | 43 | 75,4 |

| Brain tumour (hemiplegia) | 39 | 68,4 |

| Bone metastasis | 31 | 54,4 |

| Amputations | 23 | 40,3 |

| Reduction in physical ability, atrophy | 23 | 40,3 |

| Others a | 23 | 40,3 |

| ENT Cancer | 12 | 21 |

a 10 clarified answers: five breast cancer with lymphoedema; two primary bone cancer; three gastrointestinal cancer; one blood-related neoplasm.

1.3.1.4

Phase of the cancer in which these patients are taken in rehabilitation

The answers are in Table 4 .

| Number of centres saying (Yes) | Number of centres saying (No) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stable condition after treatment a | 56 | 1 |

| Remission phase | 31 | 26 |

| Phase between chemotherapy | 42 | 15 |

| Cure phase | 26 | 31 |

| Every phases | 24 | 33 |

| Others (end of life) | 2 | 55 |

a Oncologic treatment: surgery and/or chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

1.3.1.5

Way of care of these patients

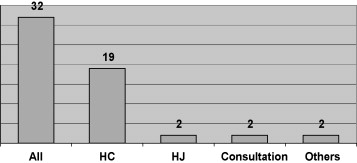

The way of care is reported in Fig. 1 . In the column “others”, there is a care in the oncology unit and one in hospitalization at home.

1.3.1.6

Working relationships established between physiatrists and oncologists

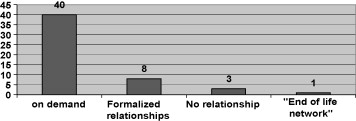

Fifty-two services answered this question ( Fig. 2 ). Working relationships are formalized only eight times (PMR vacations in oncology unit, multidisciplinary staff or network). There is a PMR centre involved in an “end of life network”.

The resorts formalized in case of health degradation are in Table 5 . (The answers concern the 57 centres). The relationships with a palliative care unit are frequent but not generalized. In a little more than a third of the answers, the solution is to keep the patient in the PMR centre.

| Number of answers | |

|---|---|

| Relationships with a palliative care unit | 34 |

| Hospitalization unit | 20 |

| Mobile unit | 30 |

| Relationships with a unit “DISSPO” (Département Interdisciplinaire de Soins de Support pour le Patient en Oncologie) | 3 |

| Relationships with an oncology network | 11 |

| Relationships only with the oncology unit (and transfer) | 41 |

| Keep the patient in the rehabilitation unit | 20 |

| All these possibilities | 3 |

1.3.2

Centres which do not take care of cancer patients

Ten centres declare not to take care of cancer patient.

Only eight of them answered the questions concerning them. Four of these eight centres have no experience of this kind of care and have no demand from oncology units ( Table 6 ). None of these eight centres wishes to develop this care.

| Number of answers | |

|---|---|

| No experience | 4 |

| Bad experience | 0 |

| No demand from oncology units | 4 |

| Not concerned by the usual activity of the centre | 5 |

| High cost | 2 |

| Unsuitability to rehabilitation when chemo or radiation therapy | 3 |

| Clinic instability of these patients | 1 |

1.3.3

Comments and wishes about the care of cancer patients

Sixty-four centres answered the question. Fifty-one (80%) of them think that PMR is not enough known in oncology.

Eighty-five per cent of the centres think that PMR is not enough developed in oncology (45 out of 53 centres taking care of cancer patients having answered the question, and 7/8 of the centres not taking care).

The wishes of physiatrists to have more trainings/informations on this possible network, of development of more adapted rehabilitation programs and of information to oncologists are reported in Tables 7 and 8 .

| Yes | No | Number of answers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| More training/informations on this network | 38 | 2 | 40 |

| Development of more adapted rehabilitation programs | 34 | 2 | 36 |

| Information to oncologists | 37 | 2 | 39 |

| Yes | No | Number of answers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| More training/informations on this network | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Development of more adapted rehabilitation programs | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Information to oncologists | 6 | 1 | 7 |

In eight centres (on 53) which think that the PMR is developed enough in oncology, six participate in an oncology network.

There were few answers to the opened question inviting to share experience of the centres on this kind of care.

It transpires from this that:

- •

difficulties taking care of a pathology with evolutionary potential: health aggravation or “uneven” evolution (twice);

- •

difficulties targeting the patients for whom the rehabilitation is going to bring profit (3 times);

- •

difficulties for the physiatrists to make palliative care palliative and to treat pain (3 times);

- •

complexity and cost of the treatment which put a brake on the care in rehabilitation (7 times).

1.4

Discussion

1.4.1

Comments concerning the investigation

1.4.1.1

Limits of the investigation

It is a descriptive study which aims to examine the care of cancer patients in PMR at one moment (in April–May, 2006), via a questionnaire. This type of investigation does not permit to go further into the questions and it is sometimes difficult to synthesize the results of the “opened questions”.

The investigation limited itself to the questionnaire and to a single sending by mail to the members of the SOFMER. It may explain the small number of centres which answered. We can notice that the answers received (67) were in the name of a centre or of a unit of PMR (while the sendings were addressed to the members of the SOFMER; about 650), that there was only one answer by centre or unit, but that we do not know exactly the number of centres concerned by these sendings.

Thus, the interpretation of the results must be careful, and the answers must be taken as indications because they are doubtless far from reflecting all the units of PMR. Besides, those who answered were probably those who were the most motivated by this care (way of selection).

However, we can notice that patients’ percentage is weak (average of 4% with important distances between the services). It is very likely that many cancer patients requiring a care in PMR are not taken care in these centres.

1.4.1.2

Type of cancer patients taken care in PMR

Spinal cord and brain injuries or amputations are the most common pathologies; this does not surprise us because these injuries lead to deficiencies and limitations of activities which require specifically PMR. However, we notice that more than 40% of the centres take care of patients presenting other kind of varied deficiencies.

On the other hand, in more than 40% of the cases, it is a global rehabilitation or the reconditionnement that motivates the follow-up in PMR.

Concerning the phase of the cancer, it is interesting to note that if it seems logical that almost the totality of the centres take care of the patients whose condition is stable or who are in phase of remission, we notice that 42% of the centres take care of the patients in all the phases of the cancer and that two centres provide palliative cares.

The modalities of follow-up are mixed (complete and day hospitalization, often both). We can notice that a single answer mentions a care in the oncology unit and another one in hospitalization at home.

In the majority of the cases, the relationships with oncology units are not formalized (staff, network…) and are made on demand. This investigation was made while the Schéma Régional d’Organisation Sanitaire de troisième génération foreseen for 2005–2010 (SROS 3) began to be applied. 1

1 SROS 2005-2010 – Circulaire DHOS/O n o 2004-101 du 5 mars 2004 relative à l’élaboration des SROS de troisième generation.

Among the subjects retained for the elaboration of this plan, there were, without compulsory link, the Following Care and of Rehabilitation and the care of cancer patients. 22 Arrêté du 27 avril 2004 pris en application des articles L. 6121-1 du Code de la santé publique fixant la liste des matières devant figurer obligatoirement dans les schémas régionaux d’organisation sanitaires.

It would be interesting to analyze how, within every region, the place of the Following Care and of Rehabilitation in the care of cancers was tackled and if the SROS 3 developed the practices.We can notice that more than a third of the centres have for only resort to keep the patient in case of health degradation. This established fact can be a limiting factor; it would have been interesting to ask if this solution was undergone or chosen. However, the relationships with palliative care units are frequent. Our investigation did not allow clarifying which kind of relationships it was: advices, care within the service of PMR or transfer into palliative care unit?

1.4.1.3

Centres not taking care of cancer patients

Few remarks can be made concerning their reasons for not taking care of these patients because, on one hand, few centres are in this situation and, on the other hand, eight only gave the causes. It does not seem to be a real choice but rather about circumstances (no request, no experience, or not concerned by the usual activity of the centre).

1.4.1.4

Wishes concerning the care of cancer patients

For the very great majority of PMR centres (including those who do not take care of cancer patients), the PMR is not enough developed in oncology. They would wish more training for themselves but also for oncologists. Indeed, we can think that the lack of relationships between oncologists and physiatrists is connected with the ignorance of the contribution of the PMR to these patients (rather than a lack of interest), as far as oncologists were in the first ones to care about the quality of life of the patients. Thus, it seems that it required that the oncologists know better the PMR but also that the specificities of the care of these patients are better known by the physiatrists.

1.4.2

Literature review on the care of cancer patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation

Situations where PMR has an important role in the follow-up of cancer patients are multiple and publications have showed its interest especially on the limitations of activities. Some former articles concerned big series. In 1996, Marciniak et al. , published a retrospective study concerning 159 patients presenting cancers of multiple causes (among which however 72 presented a primitive brain tumour); the functional gain measured by the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) was significant, even in case of metastasis. In 2000, Cole et al. studied 200 patients and showed significant gains in motor function, regardless of cancer type.

The neurological deficiencies and the limitations of activities which result from these deficiencies are in the first place. In a retrospective study, Garrard et al. put in evidence the functional gain after rehabilitation at 21 patients presenting primary or secondary neurological tumours. A little later, Greenberg et al. also showed this functional gain measured by the FIM by comparing three groups of patients presenting respectively a stroke, a glioma or a méningioma. The functional gains and the average discharge to their home were the same in the three groups. But the length of stay was significantly shorter at the patients presenting a brain tumour. This last point seemed to be favored by the department’s policy which was to improve the functional status of the cancer patients the best and the fastest they can and to discharge them for further oncologic treatments or before deterioration, new signs of activity or other complications. In neoplastic spinal cord compression, the interest of the care was underlined by Mac Kinley et al. and Parsch et al. . These authors showed that, even if their life prognosis was relatively poor, the rehabilitation allowed a functional gain maintained after discharge.

Other pathologies as the amputations or alternatives to the amputation connected with sarcomas of the members were the object of publications showing the interest of the rehabilitation .

Among the specific deficiencies due to some cancers, it is necessary to quote lymphoedemas after breast cancers which require specific cares .

Except the specific aspect on the consequences of the deficiencies, many publications report that physical exercise is very beneficial on the quality of life . Literature reviews on this subject show that, even if the methodologic quality of the studies is moderate, there is a gain during and after oncologic treatments. However, controlled studies would be necessary to rule out the possibility of an attention-placebo effect . Labourey underlines the interesting role of physical exercise to fight against fatigue.

Fatigue is a very frequent symptom at every disease’s stage. Cancer-related fatigue is frequently associated with reduced quality of life and determines the possibilities of rehabilitation. Causes are multiple: nutritional status, sleep disorders, anemia, oncologic treatments, psychological factors but also reduction in physical ability . This fatigue must be taken into account in the programs of rehabilitation proposed.

Except the fatigue, you should not underestimate the other limitants factors that developed Fayolle-Minon et al. from a case study: bad life prognosis in medium or even short-term, heaviness of treatments, psychological pressure of the patients but also their family… Complications can arise and require unplanned transfer to acute care. A recent study showed a rate significantly high of transfers to acute care for cancer patients but only those with brain tumour or neoplastic spinal cord compression: 21% versus 9,7% for patients without cancer; infections were the main cause of transfer. In 1996, Marciniak et al. had already noticed an important rate of transfers for acute medical problems: 33% of cancer patients (any types of cancer) had required at least a transfer in acute care unit, versus a 12% rate on average for all the patients of the centre during the same period, but 60% had returned to finish their program of rehabilitation.

Pain also presents specific aspects requiring a good knowledge of treatments . The difficulty, for the rehabilitation centres, sometimes far from palliative care units, to manage the “end of life” and the psychological component are factors which probably make physiatrists hesitate to take care of cancer patients except the phases of remission.

1.4.3

Reflections on the care of cancer patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation

There is little statutory instigation to the intervention of the PMR in the care of cancer as shows in the plan “cancer 2003–2007” 3

3 www.sante.gouv.fr/htm/dossiers/cancer/index2.htm .

which does not tackle this aspect.As a recent editorial of an oncologic review underlines it , it is necessary to know how to recognize needs in PMR and establish a therapeutic project by knowing the specificities and the limitants factors of the cancerous pathology and by consolidating the interest of the care in PMR.

That is why, it is necessary to develop a better knowledge of the specificities at the same moment by the rehabilitation centres, (whose demand was expressed in this investigation we made) but also by the oncologic units where the care must begin. A better knowledge by the oncologists of the contributions of the PMR must be promoted, on the ground but also in the initial education and the continual medical training. It is also essential to establish functional relationships not only with the oncologists but also with the palliative care units .

Even if the modalities of rehabilitation are the same that for the other patients , a specific organization of the unit is necessary: team conception ; work in network with oncologists and units of palliative care .

1.5

Conclusion

Even if our investigation is incomplete, it shows that rehabilitation units take care of cancer patients. Because of the improvement of the vital prognosis, the role of PMR becomes more and more important. It is important to make better known the interest of PMR in the oncology units and networks but also to develop specific care within the rehabilitation units.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Les cancers sont la première cause de décès en France et leur incidence est importante. L’International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estime qu’il y a eu 270 000 nouveaux cas en France en 2005. La détection plus précoce avec les dépistages et les progrès des traitements augmentent l’espérance de vie des patients cancéreux. Cependant, la prise en charge de ces patients en médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR) reste encore difficile même si l’apport de la MPR est souligné dans les publications des deux dernières décennies . Ces difficultés tiennent certainement à de multiples facteurs : fragilité des patients, crainte des complications ou de la fin de vie du côté du rééducateur ; méconnaissance de l’apport de la MPR du côté des oncologues. Cependant, de nombreuses manifestations cliniques des cancers se traduisent par des déficiences qui relèvent d’une prise en charge en MPR dans sa dimension proprement rééducative mais aussi de réadaptation.

Afin d’apporter des éléments de réflexion dans ce domaine, nous avons fait une enquête auprès des services de MPR. Le but de cette enquête était de connaître leur position par rapport à la prise en charge des patients présentant une pathologie cancéreuse.

2.2

Matériel et méthodes

L’enquête a été réalisée en 2006 à l’aide d’un questionnaire diffusé par courrier électronique aux différents médecins de médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR) à partir du listing mail de la Société française de médecine physique et de réadaptation (Sofmer), qui comprenait environ 650 adresses au moment de l’envoi.

Un seul envoi, réalisé en avril et mai 2006 a été effectué.

Le questionnaire comportait trois parties :

- •

la première partie s’adressait aux services qui prennent en charge des patients présentant une pathologie cancéreuse ; les questions concernaient :

- ∘

le nombre de lits d’hospitalisation (adultes, enfants, hospitalisation complète ou hospitalisation de jour),

- ∘

le nombre de patients présentant une pathologie cancéreuse par an et le nombre total de patients pris en charge en 2004 et en 2005, sans distinguer enfants/adultes,

- ∘

les déficiences et pathologies prises en charge,

- ∘

la phase d’évolution du cancer,

- ∘

les recours sanitaires possibles en cas d’aggravation ;

- •

la deuxième partie s’adressait aux services qui disaient ne pas prendre en charge de patients présentant une pathologie cancéreuse ; les questions portaient sur les raisons pour lesquelles ils ne prenaient pas en charge des patients cancéreux ;

- •

la troisième partie s’adressait à l’ensemble des services ; les questions portaient sur la place de la MPR en oncologie et sur les améliorations nécessaires pour cette prise en charge.

2.3

Résultats

Soixante-sept réponses ont été reçues. Les réponses émanent de services de l’ensemble des régions de France, ainsi que de sept centres à l’étranger (3 en Suisse, 2 en Tunisie, 1 en Belgique et 1 en Grèce).

Cinquante-sept centres prennent en charge pour rééducation des patients présentant une pathologie cancéreuse.

2.3.1

Résultats des questionnaires des 57 services prenant en charge des patients cancéreux

2.3.1.1

Type d’hospitalisation et nombre de lits

Quarante-huit services prennent en charge uniquement des adultes, six uniquement des enfants et trois des adultes et des enfants.

Le nombre de lits d’hospitalisation complète adultes est de huit à 800 par service (moyenne : 78 ; médiane : 50). Pour les enfants, ce chiffre va de huit à 70 (moyenne : 30). Trente-six services ont des places d’hospitalisation de jour pour les adultes ; le nombre de places est de deux à 80 (moyenne : 18 ; médiane : 8). Huit services ont des places d’hospitalisation de jour pour les enfants ; le nombre de places est de deux à 80 (moyenne : 21 ; médiane : 12).

La répartition en hospitalisation complète et en hospitalisation de jour est rapportée dans le Tableau 1 .