Neuromuscular Complications of Critical Illness: Evaluation of the Patient with a Suspected Critical Illness Neuromuscular Disorder

Daniel M. Clinchot

Introduction

Critical illness neuromuscular disorders are more common than you might first think. The literature is full of cases of individuals who have survived being critically ill only to emerge with profound neuromuscular dysfunction. Critical illness neuromuscular disorders are poorly understood, yet they often have serious clinical and functional impact. When a patient develops a critical illness neuromuscular disorder, there is usually a concomitant increase in ventilatory time, time in the intensive care unit (ICU), time in the hospital, and morbidity and mortality; thus demonstrating greatly increased health system costs related to such care. Spitzer et al reported that 62% of patients with prolonged weaning from ventilation had an unsuspected neuromuscular disorder (1). The greatest mortality in patients who develop critical illness neuromuscular disorder results from the underlying medical condition that resulted in the patient becoming critically ill. However, patients who become critically ill and survive their ICU stay often go on to have significant impairment directly related to a critical illness neuromuscular disorder. DeJonghe (2) reported on 95 patients who were ventilated for greater than 7 days and went on to awaken and improve. The incidence of critical illness neuromuscular dysfunction in these patients was 25.3%. Although there is no definitive treatment for these disorders, detection enables the health care team to intervene and plan appropriately. Specifically, preventing secondary complications of weakness and altered sensory function will enable the critical illness neuromuscular disorder to have the least amount of functional impact once the patient begins to improve from a medical illness standpoint. Lastly, familiarity with critical illness disorders assists the intensive care specialist in designing and implementing ventilatory weaning strategies.

Descriptions of neuromuscular complications of critical illness date as far back as the 1800s, when Sir William Osler described a syndrome of muscular wasting in an individual who had survived sepsis (3). As the care of the critically ill became more advanced, so did the spectrum of critical illness neuromuscular disorders. In the 1960s and 1970s unexplained neuropathies were described in patients who had been in a coma or who had been seriously burned or septic (4,5,6). In 1977 Bischoff and Rich described a polyneuropathy associated with gentamicin toxicity (7). Aminoglycoside toxicity has been linked to neuromuscular disorders such

as disorders of the neuromuscular junction and neuropathy regardless of whether the patient is critically ill (8). The term “critical illness polyneuropathy” was not coined until the early 1980s. At that time the full spectrum of critical illness neuromuscular disorders was not yet understood. In the late 1980s and 1990s we begin to see descriptions of a neuromuscular syndrome associated with individuals who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, and who become critically ill and require intravenous corticosteroid therapy. Subsequently the association between nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents and peripheral neuropathy became clear. In 1998 Coakley et al (9) performed electrophysiologic studies on 44 patients who were critically ill and required an ICU stay greater than 7 days. These electrodiagnostic studies revealed that only 9% of patients were normal; 43% of these patients had mixed sensory and motor nerve dysfunction. They could find no association between the type of critical illness neuromuscular disorder that developed and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score, organ failure score, or the presence or absence of sepsis.

as disorders of the neuromuscular junction and neuropathy regardless of whether the patient is critically ill (8). The term “critical illness polyneuropathy” was not coined until the early 1980s. At that time the full spectrum of critical illness neuromuscular disorders was not yet understood. In the late 1980s and 1990s we begin to see descriptions of a neuromuscular syndrome associated with individuals who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, and who become critically ill and require intravenous corticosteroid therapy. Subsequently the association between nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents and peripheral neuropathy became clear. In 1998 Coakley et al (9) performed electrophysiologic studies on 44 patients who were critically ill and required an ICU stay greater than 7 days. These electrodiagnostic studies revealed that only 9% of patients were normal; 43% of these patients had mixed sensory and motor nerve dysfunction. They could find no association between the type of critical illness neuromuscular disorder that developed and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score, organ failure score, or the presence or absence of sepsis.

Diagnostic Considerations

Critically ill patients who require ICU care and mechanical ventilation are all too often noncommunicative. They are thus unable to relay feelings of weakness or sensory abnormalities to the health care team. It is because of this that the patient with a critical illness neuromuscular disorder typically presents when the health care team determines that there is difficulty weaning from the ventilator (10). Unfortunately, even in cases with significant weakness or sensory abnormality, the critical illness neuromuscular disorder can remain undiagnosed (11).

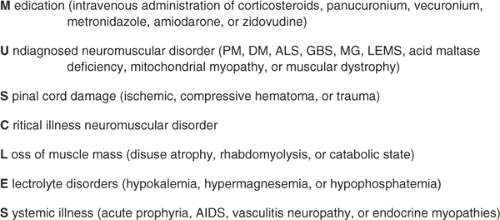

When seeing the patient who is critically ill and weak for an electrodiagnostic medicine consultation, the clinician should recall the broad differential diagnosis for individuals with weakness. The articles by Wijdicks et al (12,13) provide a nice mnemonic of the word “muscle” to support remembering the different diagnostic entities that should be considered when evaluating a patient with weakness (Fig. 14-1).

The initial electrodiagnostic medicine patient assessment should include a detailed history and physical examination. In the history, the clinician specifically needs to determine:

The time course of the critical illness

If and when the patient developed multiorgan dysfunction syndrome or sepsis

Bacterial or viral organisms responsible for infection or sepsis

The medications that have been administered during the course of the critical illness

The time course of administering corticosteroids, nondepolarizing neuromuscular junction blocking agents, and aminoglycosides (these are of particular importance)

The premorbid level of function of the person is important in understanding if the current level of functioning is a change.

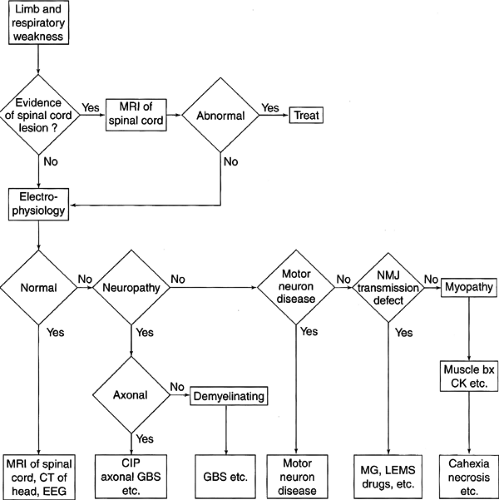

Along with the history, a detailed physical examination not only serves to confirm weakness but also allows the clinician to begin to categorize the process as upper or lower motor neuron, involving sensory and/or motor components or involving the neuromuscular junction. It is important for the clinician to examine for muscle atrophy and tenderness and assess reflexes and sensation. Although difficult in the noncommunicative patient, making some assessment of motor strength is important. In the conscious but uncooperative patient, observation of spontaneous limb movements will enable the clinician to determine if the patient has at least antigravity strength. Although mental status can be affected as a prodrome of sepsis and critical illness, critical illness neuromuscular disorders themselves typically do not affect mental status. Noting particular patterns of weakness is important in the initial patient assessment. Critical illness neuromuscular disorders are typically symmetric and do not involve the face. If cranial nerve involvement is present on physical examination, then the clinician should be suspicious for a noncritical illness–related disorder, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). Bolton (14) has developed a helpful flow chart (Fig. 14-2) to assist the clinician in determining the appropriate process for evaluating the critically ill patient who develops weakness.

In summary, the unexpected failure of ventilatory weaning, accelerated peripheral muscle atrophy, or an inability to hold the head or a limb off the bed should be clues to the health care team that a critical illness neuromuscular disorder is present. Lack of ventilatory weaning appears to be the most common patient presentation for a critical illness disorder. However, the inability to wean from a ventilator is not only a means of patient presentation, but in a clinical analysis of patients with critical illness neuromuscular disorders it was also found to be independently predicted by the development of a critical illness neuromuscular disorder (15).

Etiologic Considerations

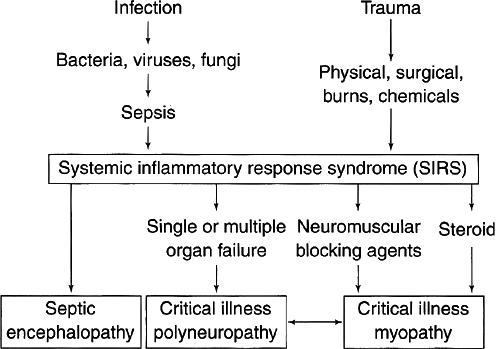

The cause of critical illness neuromuscular disorders is not clear, and it is likely multifactorial. One thing that has become quite clear is that the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) plays a significant role (16). The SIRS is a severe, overwhelming systemic response that occurs in individuals who become critically ill.

The term “SIRS” was coined in 1992 during a consensus conference between the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) (17). Bolton (16) has highlighted the significant role that the SIRS has in the development of critical illness neuromuscular disorders. The SIRS is a response that consists of both humoral and cellular components. These two components act together to create an environment in which the neuromuscular system becomes vulnerable to toxic effects. The humoral factors involved include cytokines, interleukins, arachidonic acid, proteases, free oxygen radicals, and tumor necrosis factor. The cellular responses typically involve monocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages.

The exact trigger for the SIRS can be varied. Infection, severe trauma, burns, organ transplantation, or other severe bodily assaults can set the cascade of the SIRS in motion (Fig. 14-3). Once activated, the SIRS results in significant vasodilation and sluggish flow within the most distal components of the vascular system. Sluggish flow within capillaries results in a reduced capacity to remove toxic substances that are the byproducts of cellular metabolism. This results in the neuromuscular system becoming vulnerable. The oxygen debt within the tissue and inadequate nutrient delivery create an ideal milieu for injury. In addition, toxic agents such as nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents or steroids have greater potential to cause direct injury to both nerves and muscles (Fig. 14-4). Thus, when considering aminoglycoside

toxicity, the activation of the SIRS would be expected to enhance the development of direct neurotoxic effects.

toxicity, the activation of the SIRS would be expected to enhance the development of direct neurotoxic effects.

Neuromuscular complications of critical illness can be classified as follows:

Neuropathy

Critical illness polyneuropathy

Acute motor neuropathy associated with nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents

Critical illness myopathy

Thick filament myopathy

Acute necrotizing myopathy of intensive care

Catabolic myopathy

Neuromuscular junction abnormalities

Neuromyopathy

This classification is helpful for the electromyographer in conceptualizing and classifying the appropriate diagnosis within the context of the clinical and electrodiagnostic findings. This is extremely important as the different critical illness

neuromuscular disorders can have very different functional outcomes (18).

neuromuscular disorders can have very different functional outcomes (18).

Figure 14-3 • Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). (Reprinted from Bolton CF. Neuromuscular manifestations of critical illness. Muscle Nerve 2005;32:140–163 , with permission) |

It is also clear that critical illness neuromuscular disorders develop in the pediatric population. The spectrum of critical illness disorders mimics those found in adults (19). It is important to note, however, that the greatest amount of literature describing critical illness neuromuscular disorders appears in the adult literature.

Neuropathic Conditions

CASE 1

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with bilateral lobar pneumonia secondary to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Her oxygenation progressively worsened and she developed septic shock. She required intubation and mechanical ventilation. During her ICU stay she received dopamine, amikacin, fentanyl, lorazepam, and vecuronium. On day 22, as the clinical picture improved, the nursing staff noted that she had limb weakness. Neurologic examination revealed flaccid paralysis and areflexia. After her medical condition improved she required 3 weeks of inpatient rehabilitation prior to being able to return home.

Critical Illness Polyneuropathy

Critical illness polyneuropathy (CIPN) is the best described and most studied critical illness neuromuscular disorder. CIPN is an acute, diffuse, mainly motor peripheral neuropathy due to axonal dysfunction. The predominance of motor involvement in CIPN was best described by Hund et al (20) in a study of 28 patients with moderate to severe CIPN. The electrophysiologic studies on these patients revealed that 50% of the subjects had compound muscle unit action potential (CMAP) amplitudes that were smaller than 50% of the lower limit of normal (20).

CIPN typically occurs in patients who have sepsis or multiorgan system dysfunction. The incidence has been reported to be 50% to 75% in individuals who meet these criteria (16,21,22). The severity of the peripheral neuropathy has been found to be proportional to the length of time an individual has been in the ICU. The typical presentation of individuals with CIPN is difficulty weaning from the ventilator. However, it has also been described as presenting with tetraplegia and absent deep tendon reflexes. The blood creatine kinase (CK) levels in CIPN are normal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree