Neurologic Injury

Robert H. Cofield

Scott P. Steinmann

INTRODUCTION

There are four nerves immediately in the vicinity of shoulder surgery: the axillary, the suprascapular, the musculocutaneous and the subscapular, with extensions of the brachial plexus extending very close to the surgical field. Thus, there is great opportunity for neurologic compromise during a surgical procedure. It is important to have adequate exposure so one does not become confused about location in a surgical field that may well be altered by previous injury or earlier surgery. Hemostasis is a critical component of the ability to visualize the tissue as well. In this era, minimally invasive surgery sometimes is considered important but may compromise the extent of surgical exposure. Of course, one should not do so at the risk of damage to internal structures, particularly the nerves with their variable ability to recover.

Careful preoperative assessment is critical. There are many situations where nerve injuries exist preoperatively in association with injuries or various pathologic conditions such as advanced rotator cuff tearing with muscle retraction (1). If there is uncertainty about whether or not a nerve injury exists, relative to the history and physical examination, adjunctive assessment can be useful. Often the muscles are well visualized on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and this will give a strong clue about nerve injury with the presence of muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration. An electromyelogram (EMG) is an important part of assessment should one be substantively concerned about preexisting nerve injury.

These days, interscalene block anesthesia is often an accompaniment of shoulder surgery and is an important advance in lessening the need for general anesthesia and measurably improving pain relief postoperatively. Although nerve injury associated with interscalene block anesthesia is uncommon, it has been recognized to occur (2).

Series reporting experience with postoperative nerve injuries are rather uncommon, and series from referral centers may in fact represent a concentration of worst case examples, stilted toward poorer outcomes following such injuries (3,4). These reports indicate there is clearly a risk that is present for nerve injury during surgery. The nerves should be carefully respected during surgical procedures.

Surgeons take pride in being well grounded in anatomy and the application of anatomy to surgery. Several articles are published each year by surgeons further detailing anatomic relationships of nerves to the operative field. We will describe a number of studies that have recently been published, which better define the positions of the axillary, suprascapular, musculocutaneous, and subscapular nerves about the shoulder.

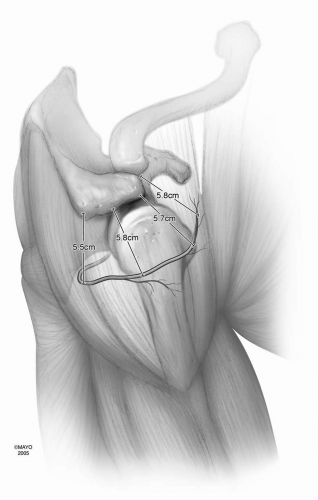

Burkhead, recognizing that many surgical approaches split the deltoid muscle and put the axillary nerve at risk, carefully studied the course of the axillary nerve within the deltoid muscle (Fig. 7-1) (5). The distance of the axillary nerve from the acromion was a mean of 5.5 cm at the posterior corner of the acromion, 5.8 cm at the midportion of the acromion, 5.7 cm at the anterolateral corner of the acromion, and 5.8 cm distal to the acromioclavicular joint. However, there was some variation with the ranges in the four locations: 3.1 to 7.3 cm, 4.3 to 7.4 cm, 4.1 to 7.1 cm, and 4.6 to 7.7 cm, respectively. Shorter distances are present in women and particularly those with shorter arm lengths. The authors further recognized that abducting the shoulder to 90 degrees decreases the distance from the nerve to the edge of the acromion by nearly 30%. An additional detailed study of the course of the axillary nerve was performed by Duparc (6) who recommended considering the position of the axillary nerve in five segments: from its origin to the inferior border of the subscapularis, from the subscapularis to the anterolateral border of the tendon of the long head of the triceps, from the triceps to the posteromedial part of the surgical neck, from the humerus to the entry into the deltoid, and, as Burkhead studied, the anterior muscular distribution of the nerve in the deltoid.

Recently, there has been a heightened interest in safe

zones for operating on the shoulder capsule during instability surgery. It is recognized that the axillary nerve is held to the shoulder capsule with loose aerolar tissue between the 5 and 7 o’clock position (considering the superior aspect of the glenoid as the 12 o’clock position) (7). The closest point between the axillary nerve and the glenoid rim is at the 6 o’clock position, where the average distance between the axillary nerve and the glenoid rim as defined by Price (8) was 12.4 mm. The average distance of the axillary nerve from the capsule throughout its course was 2.5 mm. It is also recognized that the position of the axillary nerve changes with the position of the arm. With shoulder abduction, external rotation, and perpendicular traction, the axillary nerve moves somewhat away from the glenoid. Clearly, knowing the position of the axillary nerve during surgery is of eminent importance. A tug test has been described (9) during which the axillary nerve is gently palpated on the anterior aspect of the subscapularis and simultaneously palpated as it courses from the posterior aspect of the neck of the humerus to the deltoid muscle. By gently balloting the nerve in each area, one can sense the course of the nerve across the operative field beneath the glenohumeral joint.

zones for operating on the shoulder capsule during instability surgery. It is recognized that the axillary nerve is held to the shoulder capsule with loose aerolar tissue between the 5 and 7 o’clock position (considering the superior aspect of the glenoid as the 12 o’clock position) (7). The closest point between the axillary nerve and the glenoid rim is at the 6 o’clock position, where the average distance between the axillary nerve and the glenoid rim as defined by Price (8) was 12.4 mm. The average distance of the axillary nerve from the capsule throughout its course was 2.5 mm. It is also recognized that the position of the axillary nerve changes with the position of the arm. With shoulder abduction, external rotation, and perpendicular traction, the axillary nerve moves somewhat away from the glenoid. Clearly, knowing the position of the axillary nerve during surgery is of eminent importance. A tug test has been described (9) during which the axillary nerve is gently palpated on the anterior aspect of the subscapularis and simultaneously palpated as it courses from the posterior aspect of the neck of the humerus to the deltoid muscle. By gently balloting the nerve in each area, one can sense the course of the nerve across the operative field beneath the glenohumeral joint.

Figure 7-1 Location of the axillary nerve on the undersurface of the deltoid muscle. The numbers refer to average distances of the nerve from various aspects of the acromion process (5). |

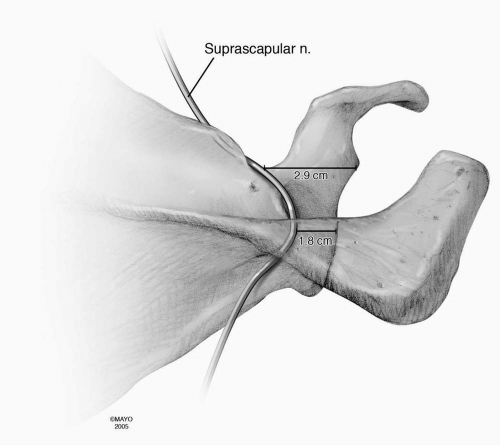

A moderate amount of attention has been directed toward the course of the suprascapular nerve and effects on the nerve by muscle retraction or rotator cuff muscle advancement. The suprascapular nerve, of course, lies on the undersurface of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle tendon units. In a dissection of 52 shoulders by Shishido (10), the distance from the superior glenoid rim to the suprascapular nerve at the suprascapular notch averaged 2.9 cm (range 2.3 to 3.5 cm) and the distance from the posterior-superior rim of the glenoid to the suprascapular nerve at the base of the scapular spine averaged 1.8 cm (range 1.2 to 2.4 cm) (Fig. 7-2). Thus, when dissecting the shoulder capsule on the inferior aspect of the rotator cuff to allow for musculotendinous advancement, a sharp dissection should not occur much greater than 1 cm medial to the glenoid rim to avoid direct contact with the nerve.

Greiner et al. (11) evaluated the vulnerability of the suprascapular nerve to muscle advancement. This neurovascular pedicle was tethered both at the suprascapular notch and by the periosteum of the supraspinous fossa. They noted the branches of the nerve were placed under tension when advancing the muscle more than 1 cm lateralward. In a study by Albritton et al. (1), they assessed tension in the reverse direction, noting that medial retraction of the supraspinatus muscle substantively changed the course of the nerve. This created increased tension on the nerve, to the point of the nerve being quite tight in all specimens at 2 to 3 cm of medial retraction. This again points out how the nerve has multiple points where it can be tethered and

also reminds us to carefully evaluate for nerve compromise before surgery is undertaken.

also reminds us to carefully evaluate for nerve compromise before surgery is undertaken.

Figure 7-2 Location of the suprascapular nerve below the surfaces of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles as the nerve courses across the top and posterior aspect of the scapula. The distances represented are average distances of the nerve from the glenoid rim (10). |

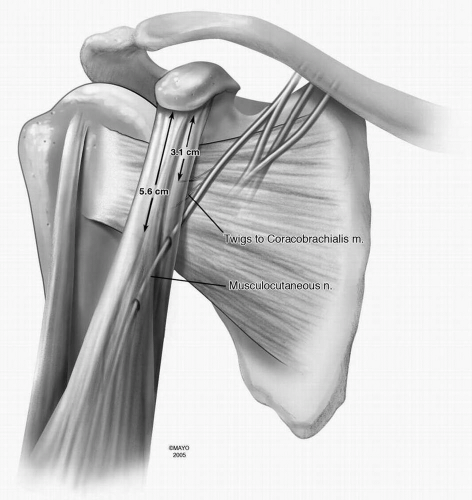

The musculocutaneous nerve has long been recognized to be at risk during surgery because it deviates laterally from the main nerve trunk to enter the coracobrachialis, to traverse the coracobrachialis, and then course between the brachialis and the biceps brachii. Flatow et al. (12) studied the anatomy of the nerve in 93 anatomic shoulder specimens. Small branches of the nerve to the coracobrachialis proximal to the main trunk entered the muscle an average of 3.1 cm below the coracoid. Some of these twigs entered as close as 1.7 cm below the coracoid. The important main trunk of the musculocutaneous nerve entered the coracobrachialis on its posterior surface an average of 5.6 cm below the coracoid, with a range from 3.1 to 8.2 cm (Fig. 7-3). Interestingly, in seven of these shoulders the main trunk of the musculocutaneous nerve passed over the coracobrachialis, sending it multiple small nerve branches. The authors mention a frequently cited range of 5 to 8 cm below the coracoid for the level of nerve penetration. However, given their data, this would not necessarily represent a safe zone for all people as the main trunk of the nerve entered the undersurface of the coracobrachialis as close as 3.1 cm below the coracoid in some individuals.

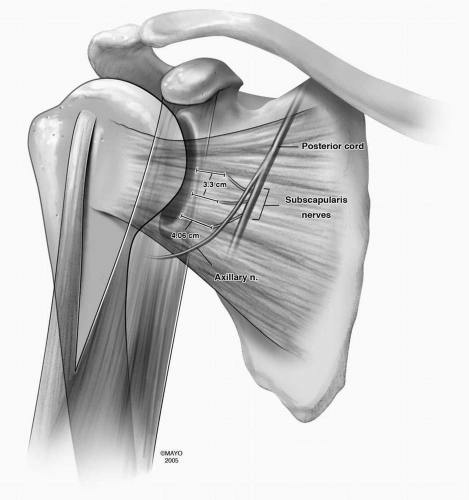

Subscapularis muscle release is common in reconstructive shoulder surgery for a number of reasons, and dissection on the anterior aspect of the muscle surface may in fact damage its innervation. In 1994, McCann et al. (13) performed an anatomic study of the subscapular nerves with a guide to electromyographic analysis. They examined 50 shoulders from 36 human cadavers, and 82% of the specimens revealed three independent nerves to the subscapularis with the remainder of the specimens having two or four nerves. The entry points of the nerves into the subscapularis were found to follow a line parallel to the vertebral border of the scapula and inferior from the medial surface of the base of the coracoid (Fig. 7-4). Similar studies were performed by Checchia (14) and Yung (15). In the first study (14), the entry of the nerves into the muscle was noted to be quite close to the surgical field, as close as 1 cm medial to the glenoid border. The mean distance though of the main upper subscapularis nerve from the border of the glenoid was 3.9 cm with the shoulder in internal rotation, 3.3 cm with the shoulder in neutral rotation, and 2.5 cm with the shoulder in external rotation. Interestingly, the authors also identified that the size of the patient did not appreciably alter the distance of the nerves to the subscapularis from the border of the glenoid.

Figure 7-3 Course of the musculocutaneous nerve as it passes under and through the coracobrachialis muscle. The distances indicated on the illustration are averages from the highest twig of the musculocutaneous nerve entering the coracobrachialis and the average distance from the tip of the coracoid to the main muscle branch entering the coracobrachialis (12). |

Yung et al. (15) examined 11 cadaveric shoulders and felt that the palpable anterior border of the glenoid rim deep to subscapularis, along with the medial border of the conjoined tendon, could serve as guides to the subscapularis nerve insertion points. In this study, all the nerve branches were no closer than 1.5 cm medial to these landmarks

for all positions of humeral rotation with the arm at the side. It was noted that the lower subscapular nerve was immediately posterior to the axillary nerve. During a standard anterior approach, potential injury to the subscapularis innervation was thought to be minimized by locating and protecting the axillary nerve because it serves as a useful guide to the insertion point of the lower subscapularis nerve, which is the nerve closest to the surgical field.

for all positions of humeral rotation with the arm at the side. It was noted that the lower subscapular nerve was immediately posterior to the axillary nerve. During a standard anterior approach, potential injury to the subscapularis innervation was thought to be minimized by locating and protecting the axillary nerve because it serves as a useful guide to the insertion point of the lower subscapularis nerve, which is the nerve closest to the surgical field.

Figure 7-4 Locations of the subscapularis nerve branches in reference to the glenoid rim. The distances are averages (14,15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|