Abstract

Method

Thirty-nine revision of ACL reconstructions were evaluated: 23 primary ACL reconstructions with bone-patellar tendon-bone graft (BPTB) revised with hamstring tendon (HT) grafts, 10 primary ACL reconstructions with HT grafts revised with ipsilateral BPTB graft (iBPTB) and finally 6 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB grafts revised with contralateral BPTB (cBPTB) grafts were compared with 78 primary ACL reconstructions (46 HT grafts and 32 BPTB grafts). Recovery of isokinetic muscle strength was evaluated at 4, 6 and 12 months post-revision surgery.

Results

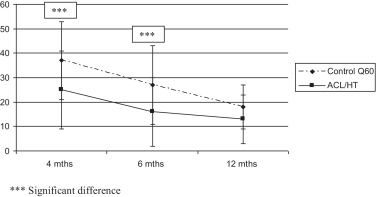

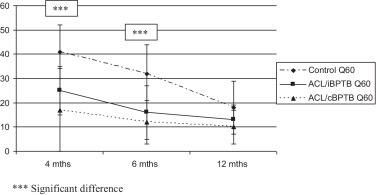

Deficits in muscle strength at 12 months post-revision ACL surgery were comparable to the one observed for primary ACL reconstruction with the same technique. At 4 and 6 months post-surgery, strength deficits for the knee extensors were less pronounced after revision ACL reconstruction with HT grafts (25% ± 16 vs. 37% ± 16; P < 0.001) and iBPTB grafts (41% ± 11 vs. 17% ± 17; P < 0.001).

Discussion

Lower strength deficits for the knee extensors after revision ACL reconstruction with HT grafts can be explained by a less intensive rehabilitation program due to lower stakes in resuming sport activities. With cBPTB, donor-site morbidity could explain the decreased strength deficits for knee extensors.

Conclusion

Deficits in isokinetic muscle strength after ACL revision seem similar to the ones observed after primary ACL reconstruction with the same surgical technique.

Résumé

Objectif

Mesurer la récupération de la force musculaire isocinétique du genou après reprise d’une reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur du genou.

Méthode

Trente-neuf reprises, 23 selon la technique aux ischio-jambiers (tendon patellaire repris par DIDT), 16 selon la technique au tendon patellaire homolatéral (10 DIDT repris par hTP) et controlatéral (6 TP repris par cTP) ont été comparés à 78 plasties de première intention (46 au DIDT et 32 au TP). La récupération de la force musculaire isocinétique a été mesurée à 4, 6 et 12 mois postopératoires.

Résultats

Le déficit musculaire à 12 mois postopératoires après reprise de ligamentoplastie est comparable à celui observé après une ligamentoplastie réalisée de première intention selon la même technique. À 4 et 6 mois postopératoires, le déficit des extenseurs est inférieur après reprise selon la technique au DIDT (25 % ± 16 vs 37 % ± 16 ; p < 0,001) et après reprise selon la technique au TP controlatéral (17 % ± 17 vs 41 % ± 11 ; p < 0,001).

Discussion

Le faible déficit des extenseurs après reprise au DIDT peut s’expliquer par un programme de rééducation qui a été moins intense étant donné un objectif de reprise sportive inférieur. Pour la technique au tendon patellaire controlatéral, la perte de force liée à la morbidité du prélèvement tendineux du genou controlatéral explique que le déficit des extenseurs soit plus faible.

Conclusion

Le déficit de force musculaire isocinétique après révision semble être identique à celui évalué après ligamentoplastie première réalisée selon la même technique chirurgicale.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The objective of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is to correct functional instability of the knee and if possible resume sport activities at the same level.

In some cases however, ACL reconstruction graft fails and knee instability returns. According to different authors, revision ACL reconstruction rates vary between 3 to 8.9% regardless of the graft site (hamstrings or bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts) .

Various reasons can explain ACL reconstruction failure, in 32 to 70% of cases a new trauma to the knee is involved . In 24 to 63% of cases, failure is due to surgical issues, i.e. misplaced graft reconstruction tunnels, graft tension and fixation defects . In rarer cases (1%), graft rupture due to knee infections have been reported and intensive rehabilitation programs were also incriminated .

With prosthetic ligaments, some biological components are linked to ACL reconstruction failures (7%) . A combination of the above listed causes is responsible for 37% of failure cases .

When the graft is torn, the decision for revision ACL reconstruction should be discussed . Thus, the work-up for revision ACL reconstruction has to include an evaluation of knee instability and its clinical validation. Plain radiographs are essential for validating previous reconstruction tunnel placement and size as well as potential arthritis; furthermore, an MRI is needed to evaluate the medial meniscus’ state.

Various grafts can be harvested such as hamstring tendon (HT) when bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) has already been used or vice versa. The contralateral BPTB can also be used as a new graft. Other potential grafts include: contralateral HT, quadriceps tendon, allograft from a donor… .

After revision surgery, the rehabilitation program should be carefully designed to follow the same objectives defined after primary ACL reconstruction, i.e. limit postoperative pain and knee swelling to restore joint ROM, muscle strength and knee stability .

Isokinetic strength training after primary ACL reconstruction has been well documented and assessed with isokinetic dynamometers. Recovery of muscle strength depends, among other things, on the tendon graft used . Loss of strength for knee extensors is to be expected with BPTB graft and loss of strength of knee flexors is predictable after surgery with HT grafts.

However, for revision ACL reconstruction, the recovery of muscle strength has not yet been properly evaluated due to the low number of patients who had this surgery. The objective of this work was to assess over a 12-month period the isokinetic strength of newly reconstructed knees with various tendon grafts. We also compared the results to primary ACL reconstructions.

1.2

Method

1.2.1

Population

Patients included had revision ACL reconstruction surgery between January 2001 and December 2010 and an evaluation of knee isokinetic strength at 4, 6 and 12 months postoperative. Only revision surgeries with HT grafts, ipsilateral or contralateral BPTB grafts were included.

This population was compared to a population of patients who had primary ACL reconstruction surgery with HT or BPTB grafts and similar longitudinal isokinetic strength evaluation during the same period.

Data were matched according to sex, age (± 2 years) and weight (± 2 kg) in order to compare patients who had revision ACL surgeries to patients with primary ACL reconstructions with the same types of graft. The various sport activities were collected even though this parameter could not be used for data matching.

Exclusion criteria: patients who had revision ACL surgeries without HT, ipsilateral or contralateral BPTB grafts, patients who experienced recurrent knee instability in spite of revision ACL reconstruction surgery and patients who did not benefit from three isokinetic evaluations over the 12-month postoperative period. Furthermore, patients who experienced postoperative complications such as anterior, posterior or dystrophic pain were taken out of the study because of the impact of this type of pain on isokinetic strength loss .

All the patients gave their informed consents to be involved in the study without any financial retribution and the isokinetic evaluation protocol was approved by the scientific committee of the physical medicine and rehabilitation department of the Nantes university hospital.

1.2.2

Standardized rehabilitation training protocol

Physical therapy started the day after surgery in order to drain the knee, restore active extension and joint ROM. Walking was resumed as soon as possible with crutches or canes for knee unloading. Patients were all sent to a rehabilitation center for 15 to 21 days in order to follow a standardized PM&R protocol monitored by physicians. The objective was to return to sedentary life 3 weeks post-surgery. No stretching or strength training of the hamstrings was authorized during a full month after revision ACL surgeries with HT grafts.

Upon discharge from the PM&R center, a written strength training protocol was handed-out and explained to each patient. Aerobic bike training was implemented 2 months postoperative with a progressive duration ranging from 15 to 90 minutes three times a week. At 4 months post-surgery, athletes were authorized to resume endurance running . At 6 months postoperative, patients were encouraged to resume more specific sport activities if their knee was effusion-free, painless, mobile and stable and according to their feelings and motivation.

1.2.3

Isokinetic evaluation

Isokinetic evaluations were conducted at months 4, 6 and 12 postoperative. We used a CybexNorm ® isokinetic dynamometer (Rankoma, NY, USA) according to a standardized protocol : 10-minute warm up on a bike, getting familiar with the isokinetic machine by performing 5 submaximal movements followed by 2 maximal movements and finally the isokinetic evaluation test.

The protocol consisted in three repetitions at the angular speed of 60°/s followed by five repetitions at 180°/s. A 20-second recovery period was allowed between both series. All evaluation tests were conducted by the same PM&R physician following the same procedure and with the patient set in the same position. The dynamometer was recalibrated monthly according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Peak force for knee flexors and extensors evaluated at the angular speeds of 60 and 180°/s were retained as study parameters in order to calculate peak torque loss of the operated side compared to the contralateral side (1- [peak force for the operated side/peak force for the healthy contralateral side]). In order to better understand the results, mean peak torque values of the healthy knee were collected and served as reference for determining isokinetic deficits.

1.3

Statistical analysis

Parameters were expressed as means and standard deviations. Deficits in isokinetic muscle strength for the two patients who had primary ACL reconstructions were averaged in order to represent only one control patient. The comparison between “revision ACL reconstruction” and “primary ACL reconstruction” populations was achieved with a Student’s t -test for paired samples after having validated that the distribution of results corresponded to the Gaussian (normal) distribution. The difference was deemed significant for P < 0.05 (SPSS software version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

1.4

Results

Thirty-nine patients, 7 women and 32 men were assessed after revision ACL reconstruction surgery. Mean age was 27 years ± 5 years. Mean time between primary ACL reconstruction and revision ACL reconstruction was 66 months [6–240 months]. Four patients were excluded from the study because of anterior pain (2 revision ACL reconstructions with cBPTB) or posterior pain (2 revision ACL reconstructions with HT). No patient was excluded from the study because of dystrophic pain. Eight partial meniscectomies were done during revision ACL reconstruction, on the internal meniscus in 5 cases and external meniscus in 3 cases. Twenty-three primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB graft were revised with HT grafts and compared to 46 primary ACL reconstructions with HT grafts. Six primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB graft were revised using contralateral BPTB graft and compared to 12 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB graft. Ten primary ACL reconstructions with HT graft were revised with ipsilateral BPTB graft and compared to 20 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB graft ( Table 1 ).

| Revision ACL reconstructions | Primary ACL reconstructions |

|---|---|

| 23 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB grafts revised with HT grafts Sports ( n ): soccer (11); basketball (4); handball (3); running (2); skiing (1), trail biking (1); judo (1) | 46 primary ACL surgery with HT grafts Sports ( n ): soccer (20); volleyball (6); basketball (4); handball (4); skiing (4); running (2); tennis (2); martial arts (2); Rugby (2) |

| 10 primary ACL reconstructions with HT grafts revised with ipsilateral BPTB grafts Sports ( n ): soccer (4); tennis (2); running (1), horse-riding (1); karate (1) | 20 primary ACL cases with BPTB grafts Sports ( n ): soccer (12); basket (2); volley (1); handball (1); skiing (1); running (1); judo (2) |

| 6 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB revised with cBPTB Sports ( n ): handball (2); soccer (1); basketball (1); running (1), dancing (1) | 12 primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB grafts Sports ( n ): Soccer (5); basketball (1); volleyball (1); handball (1); skiing (1); tennis (1); running (1); biking (1) |

The various sports practiced by the patients in the different groups are listed in Table 1 .

Mean torque values for the healthy lower limbs are comparable regardless of the groups except for the group who had revision ACL reconstructions with contralateral BPTB graft ( Table 2 ).

| MS Q 60 | MS Q 180 | MS H 60 | MS H 180 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary ACL reconstruction with BPTB grafts | 184 (43) | 122 (26) | 105 (23) | 78 (17) |

| Primary ACL reconstruction with HT grafts | 190 (45) | 127 (31) | 106 (27) | 76 (19) |

| Revision ACL reconstruction with HT grafts | 197 (44) | 126 (25) | 109 (20) | 86 (24) |

| Revision ACL reconstruction with iBPTB grafts | 182 (49) | 124 (29) | 106 (30) | 86 (28) |

| Revision ACL reconstruction with cBPTB grafts a | 165 (47) | 113 (30) | 109 (26) | 82 (19) |

a For revision ACL with cBPTB grafts, none of the knees are considered healthy, thus explaining lower peak torque values for knee extensors at 60 and 180°/sec at 4 months post-surgery.

Patients who had revision ACL reconstructions with HT grafts had significantly lower deficits of muscle strength of the knee extensors at 4 and 6 months postoperative compared to patients with primary ACL reconstructions with HT grafts ( Table 3 and Fig. 1 ). No difference was evidenced for deficits in muscle strength of the knee flexors between revision and primary ACL reconstructions with HT grafts. Patients who had revision ACL reconstructions with cBPTB grafts had significantly lower deficits in muscle strength of the knee extensors at 4 and 6 months postoperative compared to patients with primary ACL reconstructions with BPTB grafts ( Table 4 and Fig. 2 ). No difference was evidenced between revision ACL reconstruction with iBPTB graft and primary ACL revision with BPTB graft ( Table 4 and Fig. 2 ). Deficits in muscle strength of the knee flexors were similar.

| Age | Q60 4 mths | Q180 4 mths | H60 4 mths | H180 4 mths | Q60 6 mths | Q180 6 mths | H60 6 mths | H180 6 mths | Q60 12 mths | Q180 12 mths | H60 12 mths | H180 12 mths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls n = 46 | 28.8 (7.5) | 37 (16) | 33 (13) | 21 (13) | 18 (10) | 27 (14) | 24 (11) | 17 (13) | 17 (12) | 18 (9) | 15 (8) | 14 (11) | 14 (11) |

| BPTB/HT n = 23 | 27.3 (6.5) | 25*** (16) | 24** (13) | 20 (10) | 18 (13) | 16*** (14) | 16*** (12) | 14 (7) | 15 (11) | 13 (10) | 11 (8) | 10 (13) | 15 (11) |

| Age | Q60 4 mths | Q180 4 mths | H60 4 mths | H180 4 mths | Q60 6 mths | Q180 6 mths | H60 6 mths | H180 6 mths | Q60 12 mths | Q180 12 mths | H60 12 mths | H180 12 mths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls n = 32 | 26.5 (7.5) | 41 (11) | 33 (10) | 13 (11) | 14 (10) | 32 (12) | 28 (11) | 13 (18) | 9 (6) | 18 (11) | 16 (9) | 7 (4) | 7 (5) |

| HT/iBPTB n = 10 | 29 (9) | 33 (10) | 27 (13) | 15 (7) | 15 (10) | 24 (11) | 20 (11) | 15 (5) | 13 (5) | 12 (6) | 9 (5) | 6 (3) | 3 (1) |

| BPTB/cBPTB n = 6 | 27 (6.4) | 17*** (17) | 19** (15) | 18 (13) | 13 (7) | 12* (9) | 16 (13) | 13 (3) | 18 (6) | 10 (7) | 5 (6) | 13 (4) | 11 (9) |

1.5

Discussion

Regardless of the technique (HT or BPTB grafts) for revision ACL reconstruction, deficits in muscle strength for knee flexors or extensors were similar or lower than the ones observed after primary ACL reconstructions. This result was obtained after patients presenting with postoperative pain, i.e. 10.7% of included subjects, were excluded from the study . Nevertheless, with no postoperative pain, the addition of a second surgery could have had negative consequences on the recovery of muscle strength for the knee. In fact, in our population the mean 66-month delay between primary and revision ACL reconstructions could explain this result. Twenty-four months were sufficient to recover isokinetic muscle strength for knee flexors and extensors . In fact, most probably isokinetic muscle strength of the knee was completely restored prior to the new ACL rupture. Thus, revision ACL reconstruction did not aggravate pre-existing deficits in muscle strength.

Very few studies have focused on the recovery of isokinetic muscle strength of the knee after revision ACL surgeries. No longitudinal or comparative studies were found. Only, cross-sectional descriptive studies exist. Woods et al., in 2001, showed deficits in muscle strength for knee extensors and flexors at 16.5% and 4% respectively for 13 revision ACL cases with iBPTB graft at a 30-month follow-up with a 42-month delay between primary and revision ACL surgeries .

With the same technique with revision ACL reconstruction, our study showed comparable results from 12-month postoperative follow-up with 12% and 6% deficits in muscle strength of knee extensors and flexors respectively. In 2002, O’Shea and Shelbourne reported a loss in muscle strength for the knee extensors post-revision ACL reconstruction at 3% which was comparable to the loss seen after primary ACL surgery with a 49-month follow-up and a mean 71-month delay between primary and revision ACL surgeries .

To our knowledge, no study has reported results for isokinetic muscle strength after revision ACL surgery with contralateral BPTB graft. This technique induces lower deficits in muscle strength for the knee extensors than the ones observed after primary ACL reconstruction with BPTB grafts. This can be explained by the parameter used to measure the deficits in muscle strength which is in percentage and by comparing both knees.

Donor-site morbidity of the contralateral knee is responsible for absolute strength deficits at 4 and 6 months postoperative, thus the newly reconstructed knee exhibits lower deficits (17% vs. 41% at 4 months postoperative, Table 4 ). At 12 months postoperative, symmetry is not yet achieved but the difference is no longer significant.

In 2005, Grossman et al. focused on the recovery of isokinetic muscle strength after revision ACL surgery with HT grafts . Even if only 3 out of the 35 subjects benefited from this technique the authors reported a 12% decrease in hamstrings strength at 56 months follow-up. We reported similar deficits, around 10%, right from M12 postoperative, in accordance with the deficits observed in the primary ACL population, and these deficits are related to donor-site morbidity. Regarding deficits in extensors strength after revision ACL with HT grafts, we found it to be lower to the ones observed after primary ACL surgery with HT grafts. According to the method used in this work, some hypotheses can be laid out. First of all, isokinetic strength of the healthy lower limb was similar in all groups, except for the group who had revision ACL surgery with cBPTB since there was no “healthy lower limb in that group. This healthy limb was not weakened by the inactivity induced by the various central pivot ruptures and the two ACL reconstructions. Furthermore, the type of sport activity did not seem to have had an impact on the results even if the groups were not matched according to that specific parameter and that the level of sport involvement remained unknown.

However, it seems likely that patients who had 2 surgeries on the same knee might have reconsidered their athletic ambitions. Thus, the knee was not negatively impacted by a highly intensive rehabilitation program which often translates into greater deficits in isokinetic strength because of overloaded adaptation capacities of the operated knee . Most times, patients think that exercises improve strength whereas it is the state of the knee that enables the patient to perform these efforts.

Our study does have some limits. Due to the low number of revision ACL cases, we need to continue our work in order to consolidate our results. By increasing the population of patients with revision ACL surgeries with HT grafts, it could be possible for the deficits in extensors strength to disappear at 12 months post-surgery. However, the deficits in muscle strength for the extensors of the contralateral knee seem quite coherent since they are related to the donor site. For this last technique, the low number of patients can be explained by the fact that harvesting the contralateral BPTB graft requires operating on both limbs during the same surgical procedure. The immediate postoperative period is then more complex in terms of surgical risks and rehabilitation care. Another limit lies in the lack of knowledge regarding the degenerative state of the operated knees .

When degeneration was evidenced during revision ACL surgery, the authors measured the loss of static strength for the hamstrings by electromyography and compared it with the healthy side . Our study did not show similar results, probably because of the young age of patients in our population (> 30 years). Knee laxity was not measured but this parameter is not involved in recovery of isokinetic muscle strength. In fact, in case of a functional treatment for ACL rupture, the deficits in muscle strength, especially for the knee extensors, usually disappear in a few months, unless there are complications such as pain or lingering effusion .

Regarding the choice of having two controls for one patient with revision ACL surgery, it allowed us to obtain a better kinetic assessment of isokinetic muscle strength recovery for primary ACL cases. A greater number of controls would have been necessary in order to strengthen our database.

1.6

Conclusion

According to these preliminary results and in the absence of postoperative pain, the recovery of isokinetic muscle strength of the knee after revision ACL surgery regardless of the technique with HT or BPTB grafts seems similar to the recovery observed after primary ACL reconstruction with the same technique. The lower deficits evidenced for knee extensors after revision ACL surgery with BPTB can be explained by donor-site morbidity. For the technique with HT grafts, deficits in muscle strength for knee extensors are also lower; this is probably due to a less aggressive rehabilitation program and patients who toned down their athletic ambitions. These good results for isokinetic muscle strength recovery are relevant for the isokinetic follow-up of revision ACL surgeries.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Après ligamentoplastie du genou, l’objectif est de corriger l’instabilité fonctionnelle du genou et si possible de reprendre le sport au même niveau. Cependant, il arrive que cette reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur soit à nouveau défaillante avec récidive de l’instabilité du genou. Selon différents auteurs, le pourcentage de reprise de ligamentoplastie varie de 3 à 8,9 % et ceci quelle que soit la technique de reconstruction réalisée aux ischio-jambiers ou au tendon patellaire .

Différentes causes expliquent la faillite de la ligamentoplastie. Un nouveau traumatisme du genou est mis en cause dans 32 à 70 % des cas . Une cause chirurgicale est retrouvée dans 24 à 63 % des cas selon les séries avec le constat d’une anomalie de position des tunnels osseux, d’un défaut de fixation de la plastie et de tension du transplant . L’infection du genou à l’origine d’une rupture du transplant semble plus rare (1 % des cas) alors que les programmes de rééducation accélérée ont également été incriminés . Les causes biologiques sont également évoquées lorsqu’une plastie prothétique a été mise en place (7 %) . Dans 37 % des cas, une association des différentes causes précitées est présente .

Lorsque le transplant est rompu, l’indication d’une reprise doit être mûrement réfléchie . La connaissance de l’histoire de la nouvelle instabilité du genou et sa confirmation clinique sont essentielles. Les examens radiologiques à la recherche d’une anomalie de position des tunnels et de l’arthrose débutante, complétés par une imagerie par résonance magnétique nucléaire afin de vérifier l’état des ménisques sont indispensables pour planifier la nouvelle reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur. Différents transplants peuvent alors être prélevés parmi lesquelles le transplant aux ischio-jambiers quand le tendon patellaire a déjà été utilisé ou inversement. Le tendon patellaire controlatéral peut également servir de nouveau transplant. D’autres greffes sont possibles : ischio-jambiers controlatéral, tendon quadricipital, allogreffe à partir d’un donneur… .

En postopératoire, le programme de rééducation doit être planifié selon les mêmes objectifs qu’après une ligamentoplastie de première intention, à savoir, limiter les douleurs et le gonflement du genou pour récupérer les amplitudes articulaires, la force musculaire et la stabilité du genou . La cinétique de récupération de la force musculaire de la cuisse après ligamentoplastie de première intention est actuellement bien connue grâce aux mesures réalisées à l’aide d’un dynamomètre isocinétique. Cette récupération dépend entre autre du transplant utilisé . Un déficit des extenseurs du genou est attendu en cas de prélèvement du tendon patellaire et un déficit des fléchisseurs en cas de prélèvement des ischio-jambiers. Cependant, en cas de reprise de ligamentoplastie, la récupération de la force isocinétique du genou est méconnue du fait du faible nombre de patients opérés. L’objectif de ce travail a donc été de mesurer la récupération sur 12 mois de la force musculaire isocinétique du genou nouvellement reconstruit à partir de différents transplants. Une comparaison a été réalisée avec la récupération de la force après ligamentoplastie de première intention.

2.2

Méthode

2.2.1

Population

Les patients qui ont bénéficié de janvier 2001 à décembre 2010 d’une reprise de ligamentoplastie et d’une évaluation de la force musculaire isocinétique du genou à 4, 6 et 12 mois postopératoires ont été inclus. Seules, les reprises réalisées à partir des tendons ischio-jambiers et à partir d’un tendon patellaire homo ou controlatéral ont été prises en compte. Cette population a été comparée avec une population de patients porteurs d’une ligamentoplastie de première intention selon la technique aux ischio-jambiers ou au tendon patellaire qui ont observé le même suivi isocinétique longitudinal durant la même période. Un appariement a été réalisé selon le sexe, l’âge (± 2 ans) et le poids (± 2 kg) afin de comparer les patients porteurs d’une reprise de ligamentoplastie avec deux patients porteurs d’une ligamentoplastie de première intention réalisée à partir du même type de transplant. Les différentes pratiques sportives ont été répertoriées même si ce paramètre n’a pu être utilisé pour l’appariement des patients.

Ont été exclus, les patients repris avec un transplant différent des ischio-jambiers et du tendon patellaire homo- ou controlatéral et les patients qui ont récidivé une instabilité de genou malgré la reprise de reconstruction du ligament croisé antérieur. Les patients qui n’ont pas bénéficié de trois évaluations isocinétiques sur 12 mois postopératoires ont été exclus. Les patients qui ont présenté des complications postopératoires à type de douleurs antérieures, postérieures, dystrophiques ont été sortis de l’étude en raison de l’influence de ces douleurs sur les déficits isocinétiques .

Tous les patients ont donné leur consentement pour participer à l’étude sans percevoir un avantage financier et le protocole de suivi isocinétique a été approuvé par le pôle scientifique de médecine physique et de réadaptation du CHU de Nantes.

2.2.2

Protocole standardisé de rééducation et de réadaptation

Les soins de masso-kinésithérapie ont débuté le lendemain de la chirurgie afin de drainer le genou, récupérer l’extension active et les amplitudes articulaires. La marche a été reprise le plus tôt possible avec un appui complet autorisé sous couvert de deux cannes anglaises. Les patients ont tous été adressés en centre de rééducation pour une durée de 15 à 21 jours afin de réaliser un protocole standardisé supervisé médicalement. L’objectif était d’obtenir un retour à une vie sédentaire en 3 semaines. Aucun étirement et renforcement musculaire des ischio-jambiers n’a été autorisé avant 1 mois après la technique aux ischio-jambiers.

Un protocole écrit de réadaptation à l’effort a ensuite été remis et expliqué à chaque patient à la sortie du service de médecine physique et de réadaptation. La pratique aérobie de la bicyclette a été demandée à 2 mois postopératoires selon une durée progressive de 15 à 90 minutes à raison de trois fois par semaine. La reprise du footing en endurance a été autorisée à partir du 4 e mois postopératoire . La reprise des activités sportives plus spécifiques a été encouragée si le genou était sec, indolore, mobile et stable et selon les sensations et la motivation des sujets à partir du 6 e mois postopératoire.

2.2.3

Évaluation isocinétique

Les évaluations isocinétiques ont été réalisées au quatrième, sixième et douzième mois postopératoire à l’aide d’un dynamomètre isocinétique Cybex Norm ® (Rankoma, NY, États-Unis) selon une procédure standardisée : dix minutes d’échauffement sur bicyclette, familiarisation sur la machine isocinétique par la pratique de cinq mouvements sous-maximaux, puis deux mouvements maximaux, puis test isocinétique. Le protocole a consisté en la réalisation de trois répétitions à la vitesse angulaire de 60°/s suivi de cinq répétitions à la vitesse angulaire de 180°/s. Vingt secondes de récupération ont été autorisées entre les deux séries. Les tests de suivi ont ensuite été réalisés sous la direction du même médecin de médecine physique et réadaptation, en reprenant toujours la même procédure et la même position du patient. La calibration du dynamomètre a été obtenue mensuellement selon les recommandations du constructeur. Les pics de force des extenseurs et des fléchisseurs des genoux évalués aux deux vitesses angulaires de 60 et 180°/s ont été retenus comme paramètres d’étude afin de calculer le déficit du moment de force par rapport au côté controlatéral (1- [pic de force côté opéré/pic de force côté sain]). Afin de mieux comprendre les résultats, les valeurs moyennes des pics de couple de force du genou considéré sain ont été montrées car elles ont servi de référence pour le calcul des déficits isocinétiques.

2.3

Analyse statistique

Les paramètres ont été exprimés selon la moyenne et l’écart-type. Les déficits de force musculaire isocinétique des deux patients traités par ligamentoplastie de première intention ont été moyennés comme s’ils ne formaient qu’un patient témoin. La comparaison des populations « reprise de ligamentoplastie » et « ligamentoplastie de première intention » a ensuite été réalisée selon un t -test pour échantillons appariés après vérification que la distribution des résultats correspondait à la loi normale. Une différence a été jugée significative pour p < 0,05 (Logiciel SPSS 12.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, États-Unis).

2.4

Résultats

Trente neuf patients, 7 femmes et 32 hommes, ont été évalués après reprise de ligamentoplastie du genou. L’âge moyen était de 27 ans ± 5. Le délai entre la ligamentoplastie première et la reprise était de 66 mois [6–240 mois]. Quatre patients repris ont été sortis d’étude, soit 10,7 % des sujets [IC 95 % : 1,6–19,8], en raison de douleurs antérieures (2 reprises au TPc) ou de douleurs postérieurs (2 reprises au DIDT). Aucun patient n’est sorti d’étude pour douleurs d’origine dystrophique. Huit méniscectomies partielles ont été réalisées lors de la reprise, au niveau du ménisque interne dans 5 cas et externe dans 3 cas. Vingt-trois ligamentoplasties au tendon patellaire ont été reprises par plastie aux ischio-jambiers et comparées à 46 plasties de première intention aux ischio-jambiers. Six ligamentoplasties au tendon patellaire ont été reprise par prélèvement controlatéral et comparées à 12 plasties de première intention au tendon patellaire. Dix plasties aux ischio-jambiers ont été reprises par plastie au tendon patellaire homolatéral et comparées avec 20 plasties de première intention au tendon patellaire ( Tableau 1 ). Les différents sports pratiqués par les patients des différents groupes sont montrés dans le Tableau 1 .