Abstract

Background

In children with cerebral palsy, spinal equilibrium and pelvic strategies may vary according to the functional status.

Objectives

To study the relationship between motor function and pelvic and spinal parameters in a population of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (rated from level I to level IV on Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS]). A sagittal X-ray of the spine in the standing position was analyzed with Optispine ® software.

Results

The study population comprised 114 children and adolescents (mean [range] age: 12.35 [4–17]). For the study population as a whole, there were significant overall correlations between the GMFCS level on one hand and pelvic incidence and pelvic tilt (PT) on the other ( P = 0.013 and 0.021, respectively).

Discussion

Pelvic parameters vary according to the GMFCS level but do not appear to affect spinal curvature. The sacrum is positioned in front of the head of the femur (i.e. negative PT) in GMFCS level I and progressively moves backwards (i.e. positive PT) in GMFCS levels II, III and IV.

Résumé

Introduction

Cette étude s’intéresse à l’équilibre rachidien et aux stratégies développées au niveau pelvien en fonction du statut fonctionnel de l’enfant paralysé cérébral.

Background

L’évaluation clinique du patient paralysé cérébral (PC) marchant ou déambulant est basée sur l’examen neuro-moteur et l’utilisation d’échelle fonctionnelle comme la Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) ; l’évaluation paraclinique comporte des radiographies du rachis et du bassin effectuées debout et mesurées en impliquant la forme du bassin établie par l’incidence pelvienne (IP). Comme pour la population asymptomatique, les courbures rachidiennes de profil, en particulier, lordose lombaire et cyphose thoracique, sont directement sous la dépendance du paramètre IP.

Objectifs

L’objectif principal de cette étude est de montrer si la forme du bassin évaluée par l’incidence pelvienne varie en fonction du statut fonctionnel établi par la GMFCS ; l’objectif secondaire est de mettre en évidence une relation entre la fonction motrice et les paramètres pelviens et rachidiens chez une population PC marchante de niveau I à IV sur la Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS). Étude réalisée à partir d’une radiographie du rachis de profil réalisée en position debout et analysée par le logiciel Optispine ® .

Résultats

Nos résultats portent sur 114 patients dont la moyenne d’âge est de 12,35 (4–17). Il existe une corrélation significative entre la GMFCS et l’incidence pelvienne (IP) ( p = 0,013) et entre la GMFCS et la version pelvienne (VP) ( p = 0,021) pour l’ensemble de la population PC étudiée.

Discussion

Ce travail montre une adaptation des paramètres pelviens en fonction de la GMFCS sans que l’on puisse démontrer de réelles répercussions sur l’amplitude des courbures rachidiennes sus-jacentes. La version pelvienne s’ajusterait en fonction de la GMFCS, évoluant d’une position du sacrum en avant des têtes fémorales (côté négativement) pour la GMFCS de niveau I vers un sacrum qui va progressivement passer en arrière des têtes fémorales (côté positivement) pour les GMFCS de niveau II, III, IV.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a disorder of movement, muscle tone or posture that is caused by non-progressive insult to the immature or developing brain . These disorders are considered to be permanent but their clinical expression may change over time (particularly during growth phases).

In France, the prevalence of CP (2 per 1000) has been relatively stable since the 1990s. There were 1600 new cases in France in 2009 .

Researchers have developed a number of gait-based motor function classifications for (mainly diplegic) patients with CP. In 1987, Winters et al. described four gait patterns in spastic hemiplegia (drop foot, true equinus, jump gait and jump gait with rotational disorders). In 1993, Sutherland and Davids described four types of gait abnormality in spastic diplegia as a function of the knee’s position in the sagittal plan (jump knee, crouch knee, recurvatum knee, and stiff knee) . Rodda and Graham developed a management algorithm for each gait pattern in spastic hemiplegia and diplegia. Their kinematic analysis encompassed the ankle, knee, hip and pelvis and showed that movements of the pelvis in the sagittal plane varied according to the type of gait performed by the patient with CP. The pelvis was tilted forward in true equinus and then moved progressively to a neutral position or even a rearward tilt in crouch knee gait.

Clinical and radiological evaluation of the spine in children with CP is part of the overall assessment of neuromuscular and balance abilities during the growth period. Analysis of a sagittal plane X-ray of the spine in the standing position is based on now internationally renowned research (on healthy individuals) by Legaye and Duval-Beaupere , who studied the relationship between the shape of the pelvic bones (as measured by the pelvic incidence [PI]) and the amplitude of lumbar lordosis and overall spinal curvature . Pelvic incidence is a geometric pelvic shape parameter that is measured on a sagittal X-ray of the spine-pelvis-femur complex. The final PI value is not established until the end of the growth period in childhood and is specific for each individual. This shape parameter corresponds to the algebraic sum of two position parameters: the sacral slope (SS) and pelvic tilt (PT). Subsequently, many researchers have studied PI in their analyses of the sagittal plane (particularly in patients suffering from lower back pain). We consider that in CP, it is important to supplement clinical assessments and paraclinical evaluations (e.g. quantitative gait analysis [QGA]) with regular, codified examinations of the spine as the child grows. This follow-up must be based on the latest knowledge about spinal equilibrium from sagittal plane X-rays in healthy subjects , with a view to understanding the vertebral column’s behaviour in growing patients with CP and the disease’s possible impact on the spine. In the future, the Spinal Alignment and Range of Motion Measure will provide reproducible, validated clinical data on spinal equilibrium (in the sitting position) in children with CP . In a previous study , we showed that a population of patients with CP did not differ significantly from a healthy population in terms of the PI (as measured on a sagittal X-ray in the standing position). We therefore concluded that lumbar lordosis in an adolescent with CP was not correlated with the PI but resulted from the disease (e.g. due to tendon/muscle retractions of the psoas or spinal muscles or to weakness of the buttock muscles). We considered that spinal assessment and early treatment in children with CP could limit balance disorders that would otherwise perturb gait abilities.

The objective of the present study was to exploit the latest knowledge on sagittal equilibrium in healthy individuals and study the putative relationships between the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level and a number of pelvic and spinal parameters measured radiologically in a population of patients with CP . We notably sought to establish whether the GMFCS level had an impact on the various spinal and pelvic parameters.

The present study was designed to distinguish between natural variations in spinal equilibrium in patients with CP (as measured by the PI) and the impact of the disease itself on this equilibrium.

1.2

Patients and methods

On the basis of medical records, we selected patients with CP having consulted in the same paediatric physical and rehabilitation medicine department between 2002 and 2012.

We performed a retrospective, single-centre study of clinical and X-ray data obtained in children with CP. This cross-sectional study was performed at different stages of the patients’ clinical and paraclinical follow-up. The evaluations were performed once comprehensive X-ray datasets were available for each selected patient.

The study was approved by the local independent ethics committee ( Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est II ) on January 23rd, 2013.

The study’s inclusion criteria were as follows: CP, age between 4 and 17, sagittal X-ray data for the spine and pelvis in the standing position (with a large-scale view from the cervical spine to the upper third of the femur). Only patients with comprehensive X-ray and GMFCS data were included. We excluded patients whose X-rays did not show the head of the femur (making it impossible to measure PI) or the C7 vertebra (making it impossible to measure the C7 plumb line) and GMFCS level V patients (i.e. those unable to walk or to stand upright for an X-ray of the whole spine).

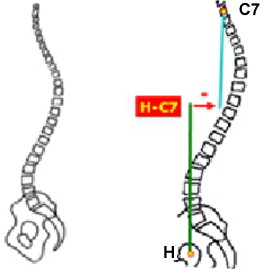

We recorded anthropometric data (age, gender and the type of impairment – hemiplegia or diplegia) and radiographic data on pelvic parameters (PI, PT and SS) and spinal parameters (the C7 plumb line, in order to assess spinal equilibrium).

If a given patient had undergone several examinations, only the earliest was taken into account.

1.2.1

The radiographic procedure

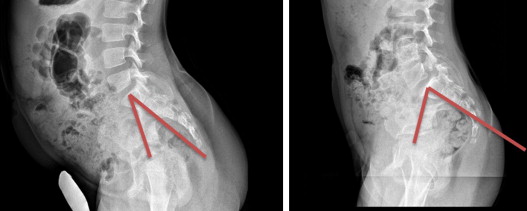

The sagittal plane X-ray measurements were not performed specifically for the present study but were part of our standard neuromuscular assessment in children with CP. The radiographic data were acquired in the standing position and covered the whole of the vertebral column and the top part of the femur. The children were allowed to wear their usual shoes and (if applicable) the braces normally used for gait. They adopted the position recommended by Faro et al. in 2004 and Horton et al. in 2005 , in order to minimize postural changes in the sagittal plane (i.e. with the hips and knees in maximum, active extension, the elbows flexed and the hands on the collar bones). The sagittal X-rays of the vertebral column and pelvis were all analyzed by the same examiner (to avoid inter-observer variability) using Optispine ® software. The intra-observer variability (according to the software) was between 0.93 and 0.99 .

1.2.2

Analysis of the X-ray data

The X-ray parameters, the technique and measurement reliability were identical to those described in the above-cited studies . The selected X-ray data included pelvic parameters (PI, PT and SS) and a spinal equilibrium parameter (the C7 plumb line) ( Fig. 1 ).

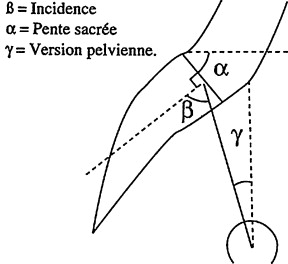

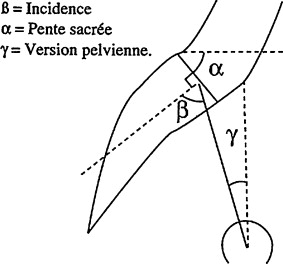

The PI corresponds to the algebraic sum of the PT and the SS. The PI is a morphological parameter that changes up until the end of the growth phase. The PI conditions the degree of overlying lumbar lordosis and the individual’s overall spinal curvature in the sagittal plane. The PT and SS are position parameters whose values change in opposite directions to yield the PI ( Fig. 2 ).

By convention, a negative PT angle corresponds to forward tilt of the pelvis (i.e. the centre of the sacral plateau is positioned in front of head of the femur) and a positive PT angle corresponds to rearward tilt (i.e. the centre of the sacral plateau is positioned behind the head of the femur).

The parameter for spinal equilibrium was the C7 plumb line ( Fig. 3 ).

1.2.3

The GMFCS

The GMFCS for patients with CP is based on voluntary movements, with a focus on sitting, transfers and mobility . The distinctions between the GMFCS’ five different levels are defined by reference to functional limitations or restrictions on activities of daily living (rather than the quality of the movement itself) and the need for hand-held mobility devices (a walking frame, a stick or crutches, etc.) or wheeled/powered mobility devices. The GMFCS can be used to evaluate all children, ranging from those with near-normal gross motor function (level I = gait with no restriction on movement) through to those with limited ability to maintain antigravity head postures and full dependence for all aspects of care (level V: the child is always transported in a wheelchair). The extended and revised version of the classification (GMFCS E&R, 2007) includes an additional age group (adolescents aged between 12 and 18) and focuses on the concepts included in the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health . The objective principal of the GMFCS is to determine the level that best describes the child’s or adolescent’s overall abilities and functional restrictions, with the emphasis on their usual activities at home, at school or in an institution (i.e. what the children and adolescents really do, rather than their supposed maximal capacities).

Each level corresponds to the mode of gait or ambulation that best described the motor performance of children and adolescents between their 2nd and 18th birthday. In the 6–12 and 12–18 age groups, different descriptions and illustrations are provided for each GMFCS level; these reflect the potential influence of environmental factors (such as the journey to and from school or an institution) and personal factors (the energy required to perform an action, and social preferences).

An examiner with experience of GMFCS grading searched for and recorded the patient’s GMFCS level on the date on which the X-ray data were acquired.

The objective of the present study was to identify putative correlations between the child’s functional capacity (according to the GMFCS) on one hand and pelvic parameters and the C7 plumb line on the other.

1.3

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with XL Stat software (Addinsoft). A Student’s t -test was used to compare mean values and a Pearson test was used to assess correlations. The threshold for statistical significance was set to P < 0.05. For the sub-analysis by GMFCS group, a Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was applied.

1.4

Results

1.4.1

The study population

The study cohort comprised 114 patients with CP (47 girls [41.22%] and 67 boys [58.77%]; mean [range] age: 12.35 [4–18]). The impairment was bilateral in 100 patients and unilateral in 14. According to the GMFCS , there were:

- •

41 level I patients (36%);

- •

44 level II patients (35.5%);

- •

15 level III patients (13%);

- •

14 level IV patients (12%).

1.4.2

Functional evaluation of our population according to the GMFCS

Our population mostly comprised children with CP who were able to walk. The 85 GMFCS level I or II patients (71.5%) walked without the need for a mobility aid. The 29 level III or IV patients (28.5%) required a mobility aid (a walking stick or walking frame). In the level IV group, gait with a mobility aid was not the usual mode of locomotion.

1.4.3

Pelvic parameters as a function of the GMFCS level

We observed that the PI was significantly lower ( P = 0.013) in the level I group than in the other three groups ( Table 1 ). Furthermore, the PT was negative or close to 0 in the level I and level II groups but was positive for the level III and level IV groups. The SS varied accordingly: the more positive the PT, the lower the SS. The mean ± SD PT (measured in degrees) was 0.34 ± 12.23° and the range of PT values was very broad (from −25° to +37°).

| GMFCS level | n | Age | PI | PT | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 41 | 11.3 (4–18) 4.3 | 40.6° (22.9–56.2) 7.5 | −1.6° (−22.0–19.9) 8.8 | 42.3° (24.8–59.4) 8.3 |

| II | 44 | 13.1 (4–18) 4.4 | 46.8° (10.2–67.7) 11.6 | −0.9° (−24.8–33.9) 13.0 | 47.6° (27.3–68.0) 11.0 |

| III | 15 | 12.6 (5–18) 3.2 | 45.9° (23.3–65.5) 11.3 | 4.3° (−17.1–22.8) 12.6 | 41.6° (18.4–57.2) 11.1 |

| IV | 14 | 12.9 (6–17) 3.9 | 45.9° (26.7–63.5) 10.9 | 6.1° (−23.3–36.8) 16.0 | 39.8° (14.5–66.8) 14.5 |

There were significant correlations between the GMFCS level and the PI ( P = 0.013) and between the GMFCS and PT ( P = 0.021) for the study population as a whole ( Table 2 ).

| P -value | r | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| GMFCS and PI | 0.013 | 0.231 | 35.9 | 44.6 |

| GMFCS and PT | 0.021 | 0.216 | −10.3 | −0.23 |

| GMFCS and C7PL | 0.490 | 0.066 | −11.4 | 24.4 |

We did not observe a significant correlation between the C7 plumb line and the GMFCS level in our population of patients with CP ( P = 0.490).

1.4.4

Comparison of the mean pelvic incidence (PI) and pelvic tilt (PT) values as a function of the GMFCS level

1.4.4.1

Pelvic incidence (PI) and the GMFCS level

We observed a statistically significant difference ( P < 0.05) in PI between GMFCS level I patients and GMFCS level II patients. In contrast, there were no significant differences between the level II, III and IV groups ( Table 3 ).

| PI | P -value | U |

|---|---|---|

| GMFCS level I vs. GMFCS level II | 0.005 | 568.5 |

| GMFCS level II vs. GMFCS level III | 0.882 | 339 |

| GMFCS level III vs. GMFCS level IV | 0.948 | 103 |

1.4.4.2

Pelvic tilt (PT) and the GMFCS level

For the study population as a whole, there was a statistically significant correlation between PT and the GMFCS level ( P = 0.021). Furthermore, there were significant inter-group differences in PT:

- •

a significant difference in PT between the level I group and the level II group;

- •

a significant difference in PT between the level II group and the level III group;

- •

a significant difference in PT between the level III group and the level IV group.

In contrast to the PI, the PT varied according to the patient’s motor function and changed with each GMFCS level ( Table 4 ).

| Age | P -value | U |

|---|---|---|

| GMFCS level I vs. GMFCS level II | 0.064 | 692 |

| GMFCS level II vs. GMFCS level III | 0.245 | 397 |

| GMFCS level III vs. GMFCS level IV | 0.456 | 87.5 |

An analysis of age in each GMFCS group did not reveal any significant differences, even though the mean age in the level I group was lower than in the other groups.

1.5

Discussion

In the present study, we considered the PI with respect to functional status (according to the GMFCS). We found that the PI is correlated with the GMFCS level. The disposition of the pelvis varied according to the patient’s functional abilities: the greater the child’s functional level (GMFCS level I), the smaller the pelvis (with a small PI). For GMFCS levels II, II and IV, the pelvis tends to broaden but remains within the normal range (a PI of around 45°). However, we could not distinguish between the three GMFCS levels .

How can one explain the variations in PI according to functional status in patients with CP? The PI is correlated with the GMFCS level and is probably influenced by gravity, posture and growth. Schematically, it is acknowledged that bipedal stance and gait (which can be represented as a series of shocks transmitted by the ground reaction force vector to the pelvis and spine) influence bone growth (particularly in the pelvis). During ontogenesis, the child will progressively build a set of postural references and adopt ever more complex balance strategies .

When a child starts to walk at the usual age or soon afterwards, the pelvic bone grows more in the vertical axis (resulting in a normal pelvic shape and PI) than in the horizontal plane (relative to a patient who walks very little or has started to walk late). On the basis of this observation and considering the GMFCS group analysis, our results showed a significant difference in the PI between the level I group and the other groups. In contrast, we did not observed a significant difference in PI between the other three groups, this may have been due to the low numbers of participants in the GMFCS level III and IV groups. It would be useful to perform a longitudinal, comparative study of a cohort of healthy subjects and a population of patients with CP, in order to more reliably track changes in pelvic parameters throughout the growth period.

The mean PI in the GMFCS level I group (40.6°) was significantly lower than those for healthy individuals (45.97°) and for patients with CP in general (44.82°) : it is possible that this is because the level I group comprised relatively young patients (with a mean age of 11.3 years, versus 12.7 for the GMFCS level II, III and IV groups). The definitive PI (an index of pelvic morphology) may not have been reached because recent studies have shown that this parameter changes throughout the growth period .

We did not include GMFCS level 5 patients in the present study, although the rehabilitational value of verticalization therapy in this type of patient is subject to debate. In fact, verticalization as early as possible promotes better growth of the spine/pelvic/femur complex, (i.e. growth of the pelvis in the vertical axis) and limits the value of the PI and thus the potential impact on spinal curvature (such as lumbar hyperlordosis). Furthermore, verticalization with passive or active control of sagittal curvature (in order to limit lumbar hyperlordosis) would help to position the psoas muscles and prevent them from retracting. A high PI is accompanied by marked lumbar lordosis, which leads progressively to the appearance of pain and (in some cases) spondylolysis. When a child with CP is not verticalized or encouraged to walk for many years, the neuromuscular disorders associated with increases in weight and height (tendon and muscle retractions, bone disorders, etc.) worsen. Ultimately, interventional treatment is considered and multisite surgery is often suggested (together with botulinum toxin injections, in some cases) without systematically taking account of the possible impact on the spine. If a patient has a high PI, the work and stress associated with gait or ambulation will affect the lumbar spine; treatment-refractory pain may then appear and thus limit the patient’s functional capacity (even when gait is possible). The present study was not designed to establish whether gait, ambulation and ability to perform transfers can be maintained in children with CP. When the spinal and pelvic muscles are weak (and thus are no longer able to resist gravity efficiently) and the PI is high, taking account of the latter parameter may help to determine the mechanical stress at the lumbar-sacrum hinge induced by verticalization. Children with CP with limited gait abilities should be placed in the sitting position (with the pelvis tilted forward slightly) as early as possible, in order to improve growth of the pelvis and spine and maintain the equilibrium of the spine-pelvis complex when walking starts (even if this occurs late).

Other factors (not studied here) are involved in the equilibrium of the pelvis above the head of the femur, regardless of the hip’s position in the horizontal plane (anteversion of the femur) and the force and selectivity of the sub/suprapelvic muscle systems. These elements will influence the spatial position of the pelvis and, progressively, the patient’s overall balance and gait abilities and the possible appearance of functional signs.

It is known that in healthy individuals, the PI is correlated with spinal curvature . For patients with CP, we have to take account of all the various neuromuscular disorders that may affect these individuals. When spinal curvatures are not correlated with the PI (whatever its magnitude), we can be sure that there are primary or secondary problems (progressive bone deformations and neuromuscular disorders, such as tendon and muscle retractions) or tertiary problems (compensatory phenomena, such as lumbar hyperlordosis or accentuation of the sagittal offset of C7). These secondary and tertiary disorders are not caused directly by the permanent brain lesion at the origin of CP; they occur during growth under the influence of gravity (referred to as “lever arm disease” by Gage ). This is why future rehabilitational treatment must take account of the shape of the pelvis, the amplitude of spinal curvatures and the presence or absence of a correlation between the PI and spinal curvatures, in order to provide comprehensive care, prevent the appearance of pain and maintain functional abilities and gait.

The positional parameters vary as a function of the PI: the greater the GMFCS level (with an increasing need for mobility devices), the higher the PT angle ( P = 0.021). This translates into a progressive rearward tilt of the pelvis. This finding agrees with the results of the QGA study by Rodda and Graham , who observed a trend toward rearward tilt for crouched gait and forward tilt for true equinus. In our population of patients with CP as a whole, the PT angle (0.25°) was lower than that found in healthy subjects (7.14°). In general, a low PT angle (i.e. close to 0°) corresponds to equilibrium for the muscles, with the pelvis positioned just above the head of the femur. In contrast, a high PT angle (with the pelvis further away from the head of the femur) requires effort and fatigues the muscles. We were not able to classify our patients by the type of impairment because the latter was often asymmetric and was associated (to a variable extent) with two different gait patterns; this constitutes a study limitation.

On the basis of our clinical experience, we observed that the GMFCS level I group comprises patients with predominantly distal impairments. When the ground force reaction vector moves in front of the centre of the knee joint during the stance phase, the equilibrium strategy consists in tilting the pelvis forwards (thus explaining the null or negative PT).

This becomes progressively more difficult to achieve (at GMFCS levels II, III and IV) and affects the kinematics of the knees and the hips and (potentially) the PT angle. The PT is a positional parameter that varies according to the PI. In the present work, we did not observe excessive PT values (relative to normative data from healthy individuals), although (a) there were few patients in the level III and IV groups and (b) GMFCS level V patients were not studied here. Our results showed that PT varies according to the patient’s functional potential: each GMFCS level is associated with a mean PT value that must be analyzed by taking account of the patient’s overall neuromuscular status (e.g. the effectiveness of the sub- and suprapelvic muscle systems). Although the PT varies as a function of the GMFCS level, we cannot extrapolate this relationship to patients with CP in general. Other studies will be necessary because in order to make valid comparisons, the value of the PT (positive or negative) will have to be correlated with the femur position by measuring the pelvis-femur angle. For a given PT, a patient with a vertical femur (i.e. a pelvis-femur angle greater than 180°) will not necessarily have the same functional abilities as a patient with hip flexion (i.e. a pelvis-femur angle below 180°).

The C7 position is considered to be normal when the C7 plumb line passes through the sacral plateau. This can be considered to be a biometric signature and varies from one individual to another. Regardless of motor function (i.e. the GMFCS level), the C7 plumb line may be positioned either in front of or behind the sacral plateau.

1.6

Conclusion

The present study measured the PI in a population of young patients with CP. We can confirm that the GMFCS level (motor function) in our CP population had an impact on the various pelvic parameters measured but not on the C7 plumb line.

In our GMFCS level I patients, we observed a small PI and a negative PT (confirming Rodda et al.’s results showing forward tilt of the pelvis in patients with spastic diplegia and true equinus). However, our study focused on the patients’ functional status rather than the type of impairment. It would be interesting of reconsider the functional classification of spastic diplegia and hemiplegia by evaluating and accounting for the muscle systems that are involved in pelvic equilibrium (i.e. both the subpelvic muscles and the suprapelvic muscles [the psoas, buttock and spinal muscles]). On the basis of our present data, we were unable to identify the cause of the variations in PT in the four selected GMFCS levels because (a) the numbers of participants in our groups were low and (b) the position of the femur with respect to the vertical was not specified. Likewise, it is difficult of explain the small differences in the PI (e.g. between the GMFCS level I and II groups). It is not clear whether this is due to the indirect impact of CP-related disorders on the growth of the pelvis (and thus the PI) or a “primary” interindividual variation in the PI (as is observed in healthy populations).

The clinical translation of the mismatch between the PI and the overlying spinal curvatures is related to neuromuscular disorders that develop progressively and reduce the patient’s functional potential by inducing balance problems and pain.

In the longer term, we would like to improve spinal equilibrium, prevent spinal pain and facilitate gait or ambulation in our patients with CP.

The evaluation and treatment of patients with CP must include an assessment of the spino-pelvic junction, with a view to improving spinal equilibrium, preventing spinal pain and facilitating gait or movement. Ultimately, analysis of the spine-pelvis-femur complex (mainly based on static data from X-rays in the standing position, at present) should be supplemented by a QGA .

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the documentation service at CMCR des Massues (particularly Pascale Raillard, for assistance with performing and formatting the literature search).

The authors thank Drs Aurelie Lucet and Donatien Gouraud ( centre de rééducation de Bois Larris ) for reading through the manuscript.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La paralysie cérébrale (PC) est définie au sens de cerebral palsy des Anglo-Saxons comme l’ensemble des troubles du mouvement et/ou de la posture et de la fonction motrice, dus à un désordre, une lésion, ou une anomalie non progressive d’un cerveau en développement ou immature . Dans la paralysie cérébrale, les troubles sont dits permanents mais peuvent revêtir une expression clinique changeante dans le temps, en particulier durant la phase de croissance.

La prévalence de 2/1000 environ est relativement stable depuis les années 1990 et l’incidence est de 1600 nouveaux cas par an en France en 2009 .

Différents auteurs proposent de classer les patients PC en fonction de leur schéma de marche, en particulier pour les diplégiques. Winters et al. en 1987 décrivent 4 types de marche chez l’hémiplégique ( drop foot , true equinus , jump gait et jump gait avec troubles rotationnels); Sutherland and Davids en 1993 décrivent 4 types de marche anormale chez le diplégique spastique en fonction de la position du genou dans le plan sagittal ( jump knee , crouch knee , recurvatum knee , stiff knee ) . Rodda et Graham proposent un algorithme de traitement pour chaque schéma de marche tant chez l’hémiplégique que le diplégique. L’analyse cinématique porte sur la cheville, le genou, la hanche et le bassin : cette étude montre que les mouvements du bassin de profil varient en fonction du type de marche présenté par le patient PC. De la position antéversée pour le true equinus , le bassin passe progressivement à la position neutre voire rétroversée pour le crouch knee .

L’évaluation clinique et radiologique du rachis de l’enfant PC fait partie du bilan global, effectué pour suivre les capacités neuro-motrices et d’équilibre au cours de la croissance. L’analyse d’une radiographie du rachis debout de profil s’appuie sur les travaux de Legaye et Duval-Beaupère qui font référence sur le plan international : ces auteurs ont établi, pour la population asymptomatique, une relation entre la morphologie osseuse du bassin, exprimée par la valeur de l’incidence pelvienne (IP), et l’amplitude de la lordose lombaire sus-jacente puis de proche en proche des courbures rachidiennes globales du rachis . L’incidence pelvienne est un paramètre de forme du bassin qui se mesure à partir d’une construction géométrique sur une radiographie de profil du complexe spino-pelvi-fémoral. La valeur de l’incidence pelvienne s’établit définitivement en fin de croissance , elle est spécifique à chaque individu. Ce paramètre de forme correspond à la somme algébrique de deux paramètres de position correspondant à la pente sacrée et à la version pelvienne. Par la suite, de nombreux auteurs ont montré l’intérêt de ce paramètre dans l’analyse du plan sagittal en particulier pour les patients souffrant de lombalgie. Il nous semble important, pour les patients PC de compléter les évaluations cliniques ou paracliniques (ex. : analyse quantifiée de la marche) par un examen codifié du rachis et de suivre ce rachis tout au long de la croissance. Ce suivi doit s’appuyer sur les connaissances actuelles de l’équilibre rachidien obtenues à partir de radiographies de profil chez la personne asymptomatique afin d’approcher, pour la population PC le comportement de la colonne vertébrale en période de croissance et les conséquences éventuelles de la maladie sur ce rachis. À l’avenir, l’utilisation du Spinal Alignment and Range of Motion Measure (SAROMM) apportera des éléments cliniques reproductibles et validés sur l’équilibre rachidien des enfants PC en position assise . Dans une étude précédente , nous avions montré que la population PC ne présentait pas de différence significative dans la valeur de l’IP par rapport à la population asymptomatique (IP mesurée sur une radiographie de profil du rachis, réalisée en position debout). Nous en déduisions que la lordose lombaire d’un adolescent PC qui n’était pas en adéquation avec l’IP était une conséquence de la maladie (par ex. : par rétractions tendino-musculaires des psoas ou des spinaux ou par faiblesse des fessiers). Nous considérions que l’évaluation du rachis de l’enfant PC et la prise en charge précoce permettraient de limiter les troubles d’équilibre qui eux-mêmes perturbent les capacités de déambulation.

L’objectif de cette étude est de se servir des connaissances actuelles sur l’équilibre sagittal du patient asymptomatique afin de corréler différents paramètres pelviens et rachidien d’une population de patients PC avec le statut fonctionnel gradué par la GMFCS . La GMFCS a-t-elle un impact sur les différents paramètres pelviens et rachidiens mesurés radiologiquement ?

Ce travail répond à notre volonté de faire la part entre l’équilibre naturel du patient PC compte tenu de son IP et les conséquences que peut avoir la maladie sur cet équilibre.

2.2

Patients et méthode

Pour ce travail, nous avons sélectionné les dossiers de patients PC de 2002 à 2012. Tous les patients proviennent du même établissement, et ont été accueillis dans le service de médecine physique et réadaptation pédiatrique.

Il s’agit d’une étude rétrospective mono-centrique établie à partir de critères cliniques et radiographiques d’enfants PC. Cette étude transversale est effectuée à un âge variable dans le suivi clinique et paraclinique du patient, l’évaluation se faisant au moment où nous disposions de données radiographiques complètes pour chacun des patients sélectionnés.

Cette étude a été approuvée par le Comité de protection des personnes Sud-Est II le 23 janvier 2013.

Les critères d’inclusion retenus sont : la déficience PC, les patients âgés de 4 à 17 ans et possédant une radiographie du rachis et du bassin de profil en position debout (grand format, de la colonne cervicale au 1/3 supérieur des fémurs). Seuls les patients pour lesquels nous avions le dossier radiographique complet et la GMFCS ont été inclus dans ce travail. Sont exclus de ce travail les patients dont les radiographies ne permettent pas de voir les têtes fémorales (mesure de l’incidence pelvienne impossible) ou la vertèbre C7 (mesure de l’aplomb de C7 impossible), ainsi que les patients dont la GMFCS est de niveau V, c’est-à-dire sans capacité de déambuler et de se tenir debout pour permettre une radiographie du rachis dans sa totalité.

Les données recueillies sont anthropométriques, avec l’âge, le sexe, le type de déficience (hémiplégie ou diplégie), ainsi que les données radiographiques avec les paramètres pelviens (incidence pelvienne, version pelvienne et pente sacrée) et un paramètre rachidien afin d’évaluer l’équilibre du rachis par la mesure de l’aplomb de C7.

S’il existait plusieurs examens complets pour un même patient, seul le premier a été retenu.

2.2.1

Technique radiographique

Les radiographies n’ont pas été réalisées spécifiquement pour cette étude, puisqu’elles font partie de l’examen neuro-moteur du patient PC en cours de croissance. Elles ont été réalisées en position debout de profil et englobent l’ensemble de la colonne vertébrale ainsi que la partie proximale des fémurs. Les enfants sont invités à garder leurs chaussures habituelles, le cas échéant à conserver les attelles fonctionnelles de marche habituellement portées, puis à adopter la position recommandée par Faro et al. en 2004 et Horton et al. en 2005 afin de minimiser les changements posturaux dans le plan sagittal : hanches et genoux en extension active maximale, coudes fléchis, mains à hauteur des clavicules. Concernant la mesure des paramètres radiologiques de profil de la colonne vertébrale et du bassin sur la radiographie du rachis de profil, l’analyse a été faite par le même examinateur (pour éviter la variabilité inter-observateur) à l’aide du logiciel Optispine ® . La variabilité intra-observateur des mesures à l’aide de ce logiciel est comprise entre 0,93 et 0,99 .

2.2.2

Technique de mesure des radiographies

Les paramètres radiographiques retenus, la technique et la fiabilité des mesures sont identiques aux études précitées . Les données radiographiques retenues sont composées des paramètres pelviens (version pelvienne et incidence pelvienne) et d’un paramètre d’équilibre rachidien (aplomb de C7).

Les paramètres pelviens sont représentés par l’incidence pelvienne (IP), la version pelvienne (VP) et la pente sacrée (PS) ( Fig. 1 ).