Mini-open and Open Techniques for Full-Thickness Rotator Cuff Repairs

Edward V. Craig

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

The ultimate failure of the terminal fibers of the rotator cuff and subsequent full-thickness tearing is multifactorial in its etiology and includes intrinsic degeneration of tendon, poor potential for healing, vascular insufficiency, repetitive trauma, and extrinsic mechanical pressure from the surrounding coracoacromial arch (1, 2, 3, 4). Whatever the factors that produced the tear, surgical treatment aimed at decompressing the rotator cuff from impingement by the overlying acromion and distal clavicle, in combination with direct surgical repair of the tendons, offers the most predictable means of relieving pain and restoring movement, strength, and function to the shoulder (5) (Fig. 25-1). Although reports of direct repair without acromioplasty have shown encouraging results, it seems logical, in the face of subacromial space surgery, to increase the space within which the repaired cuff can function.

The primary indication for operative treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome and full-thickness tear is pain associated with documented subacromial impingement that has failed nonoperative treatment, or

a symptomatic, documented full-thickness tear of the tendon. The rationale for surgical treatment of the fullthickness tear, in combination with an anterior acromioplasty, is that removal of the offending structure producing mechanical wear and restoration of tendon integrity can be expected to relieve the pain, minimize the likelihood of tear extension, and maximize the strength and motion of the shoulder (6). Lack of strength alone is much less often an indication for surgical repair. I tell the patient the most predictable result of surgical treatment is pain relief. However, return of strength is unpredictable and depends on many factors, including the size of the tear, the length of time the tendon has been torn, the adequacy of the soft tissue and quality of the tendon, the extent of associated muscle atrophy or damage, whether the muscle still has viable muscle or has been replaced by fat or scar, associated deltoid problems, maintenance of the repair of the tendon over time, and adequacy of the rehabilitation (7). For this reason, unless a patient is absolutely incapacitated by arm weakness from the rotator cuff tear, I have been reluctant to suggest surgical treatment in the absence of significant pain symptoms. An exception to this is the case of severe rotator cuff weakness from a tear following acute trauma. If the patient had no weakness before a traumatic event and then clearly had a traumatic event that produced the tendon tear, I often elect to repair the tendon even in the absence of pain, particularly if magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggests good-quality muscle and tendon. This is because the tendon is usually not retracted or scarred, and a good-quality repair usually can be achieved. Another difficult decision-making process occurs in the face of a young patient with a documented, repairable full-thickness tear with minimal or no pain. This decision making is made more difficult by the observation that full-thickness tears often increase in size over time, combined with the experience that smaller tears are technically easier to repair than larger ones, whether done by open or arthroscopic techniques. Because of these factors, a valid argument can be made to repair a small tear, even if the symptoms are minimal, provided the patient understands well the pros and cons of the decision-making process.

a symptomatic, documented full-thickness tear of the tendon. The rationale for surgical treatment of the fullthickness tear, in combination with an anterior acromioplasty, is that removal of the offending structure producing mechanical wear and restoration of tendon integrity can be expected to relieve the pain, minimize the likelihood of tear extension, and maximize the strength and motion of the shoulder (6). Lack of strength alone is much less often an indication for surgical repair. I tell the patient the most predictable result of surgical treatment is pain relief. However, return of strength is unpredictable and depends on many factors, including the size of the tear, the length of time the tendon has been torn, the adequacy of the soft tissue and quality of the tendon, the extent of associated muscle atrophy or damage, whether the muscle still has viable muscle or has been replaced by fat or scar, associated deltoid problems, maintenance of the repair of the tendon over time, and adequacy of the rehabilitation (7). For this reason, unless a patient is absolutely incapacitated by arm weakness from the rotator cuff tear, I have been reluctant to suggest surgical treatment in the absence of significant pain symptoms. An exception to this is the case of severe rotator cuff weakness from a tear following acute trauma. If the patient had no weakness before a traumatic event and then clearly had a traumatic event that produced the tendon tear, I often elect to repair the tendon even in the absence of pain, particularly if magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggests good-quality muscle and tendon. This is because the tendon is usually not retracted or scarred, and a good-quality repair usually can be achieved. Another difficult decision-making process occurs in the face of a young patient with a documented, repairable full-thickness tear with minimal or no pain. This decision making is made more difficult by the observation that full-thickness tears often increase in size over time, combined with the experience that smaller tears are technically easier to repair than larger ones, whether done by open or arthroscopic techniques. Because of these factors, a valid argument can be made to repair a small tear, even if the symptoms are minimal, provided the patient understands well the pros and cons of the decision-making process.

The indications for resection of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint in the surgical treatment of cuff tears include clinical tenderness or radiographic changes of arthritis in the AC joint, inferior protruding osteophytes contributing to the impingement syndrome, and a need for additional exposure of a retracted supraspinatus tendon (SST).

There are really no absolute contraindications for surgical treatment of symptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Symptoms insufficient to warrant the risks of surgery may be considered by some to be a relative contraindication. Likewise, a patient’s medical condition may preclude surgery or anesthesia. Another consideration is the presence of a medical condition, such as the uncontrolled muscle activity of Parkinson disease and paraplegia of the weight-bearing shoulder, which have been associated with a high failure rate of surgical repair of the rotator cuff. Perhaps the most common contraindication to surgical treatment is the inability or unwillingness of the patient to participate postoperatively in protection of the tendon repair and in the rehabilitation program, both critical to the success of surgery.

There are many surgical treatments available for symptomatic rotator cuff tears, including open and partial repair, arthroscopic and partial repair, and débridement without rotator cuff repair. (Arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery is covered elsewhere.) With a mini-open rotator cuff repair, the bony work (anterior acromioplasty, bursectomy, lysis of adhesions, preparation of greater tuberosity area, and tendon edges) is accomplished arthroscopically. A small “split” in the deltoid without deltoid detachment is used to repair and suture the rotator cuff tendon. This can be done through a separate skin incision (as with an open rotator cuff repair) or an extension of one of the arthroscopic portals. In a true open repair, both the anterior acromioplasty and the rotator cuff repair are done as open procedures. The advantage of arthroscopic decompression and mini-open repair is that there is no deltoid detachment, which may produce less postoperative pain. In addition, extensive dissection is avoided and there is minimal interference with muscle groups. Arthroscopy also allows a more complete examination of the glenohumeral joint than is typically done with an open rotator cuff repair. If other pathologies are encountered (superior labrum anterior and posterior lesion, labral detachment, or tearing), intra-articular synovectomy or cartilage surface débridement, these can be dealt with more easily arthroscopically than with an open procedure can also be performed.

My indications for arthroscopic decompression and mini-open repair of the tendon are those cases in which minimal exposure of the rotator cuff is needed, the tendon is not retracted, the tendon tear does not involve the subscapularis, the biceps is not dislocated, and significant mobilization of the rotator cuff is not required for repair (8). In my opinion, a prerequisite for a mini-open repair is an “expeditious acromioplasty,” as a lengthy arthroscopic decompression and débridement can create significant swelling from fluid extravasation, making it difficult to expose and repair the rotator cuff through a small deltoid split. The ideal candidate for the mini-open rotator cuff repair is a patient with an isolated SST tear or a nonretracted supraspinatus and infraspinatus tear, if the arthroscopic decompression can be accomplished relatively quickly.

My indications to do the entire procedure as an open procedure, including an open anterior acromioplasty and cuff repair, include the following:

A large or massive retracted rotator cuff tear, which requires the releases of soft tissue, adhesions, capsule, rotator interval, and coracohumeral ligament (CHL) for mobilization and secure repair of the tendon, when this cannot be accomplished arthroscopically (9, 10, 11).

A large isolated subscapularis repair with or without medial biceps dislocation since it is often difficult to retrieve the subscapularis through a portal extension of a mini-open technique and arthroscopically.

If there is any consideration of arthroplasty in the presence of glenohumeral arthritis.

Revision rotator cuff surgery, as the muscle planes are often obscured; separation of both healthy rotator cuff tissues and surrounding soft tissue is difficult, as more extensive exposure of the deltoid and rotator cuff is usually necessary.

If elaborate coverage methods for rotator cuff deficiency are considered, such as tendon transfers, patch reconstruction, or allograft reconstruction (10).

Deltoid avulsion, retraction, or insufficiency from prior surgery requiring extensive repair or mobilization of deltoid muscle.

Arthroscopic experience of the surgeon or operating team is such that a more effective repair and reconstruction can be performed open.

The advantages of performing the entire procedure as an open procedure are increased exposure, the ability to better define healthy rotator cuff and deltoid tissue, the better ability to release a contracture and adhesions, better ability to mobilize the tendon, and, for some surgeons, better ability to precisely define the surgical pathoanatomy. In addition, an open anterior acromioplasty as part of a surgical approach in some instances may be done more rapidly than the arthroscopic portion of the mini-open repair.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The patient with subacromial impingement syndrome usually presents with a gradually progressive history of pain aggravated with use of the arm above shoulder level. As the symptoms persist and progress, the pain, initially present only with activity, may become present at rest and especially at night, awakening the patient from a sound sleep. The patient with a full-thickness rotator cuff tear may or may not notice weakness in the arm. With small cuff tears, strength may be maintained surprisingly well, although the patient may notice diminished endurance and fatigability of the arm when it is used in the overhead position. Patients

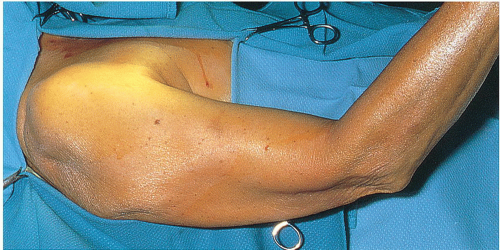

with cuff tears often note that the pain affects such activities as opening doors, reaching behind the back to do bra straps, reaching high shelves, or participating in sports such as tennis, racquetball, and swimming. On physical examination, inspection often reveals few abnormalities. A patient with a rotator cuff tear may have a rupture of the long head of the biceps or muscle atrophy in the supraspinatus fossa, although atrophy generally accompanies larger tears of long duration. There may be fullness in the subdeltoid area as joint fluid fills the subacromial space. Occasionally a patient with a full-thickness tear will present with an AC joint “ganglion.” This is, in fact, glenohumeral joint fluid that has leaked out into the subacromial space and through the eroded inferior capsule of the AC joint. This fluid sac gradually enlarges superiorly to present as a ganglion on top of the AC joint. It is important to recognize that the underlying pathology is not localized to the AC joint but reflects the more difficult problem of a full-thickness tear that is usually large. Palpation of the affected shoulder not uncommonly reveals AC tenderness especially if AC arthrosis is present. There is usually a palpable subdeltoid soft crepitation, which may represent a subacromial bursal fluid, a thickened bursa, or a torn tendon moving under the coracoacromial arch. A patient with subacromial impingement syndrome without rotator cuff tearing may have normal passive range of motion; however, it is not uncommon for a mild frozen shoulder to accompany this syndrome. In the latter case, there is usually some restriction of motion passively in forward elevation, external rotation, and internal rotation. In the presence of a fullthickness rotator cuff tear, passive range of motion is often remarkably normal, as joint fluid leaks out and lubricates the subacromial space.

with cuff tears often note that the pain affects such activities as opening doors, reaching behind the back to do bra straps, reaching high shelves, or participating in sports such as tennis, racquetball, and swimming. On physical examination, inspection often reveals few abnormalities. A patient with a rotator cuff tear may have a rupture of the long head of the biceps or muscle atrophy in the supraspinatus fossa, although atrophy generally accompanies larger tears of long duration. There may be fullness in the subdeltoid area as joint fluid fills the subacromial space. Occasionally a patient with a full-thickness tear will present with an AC joint “ganglion.” This is, in fact, glenohumeral joint fluid that has leaked out into the subacromial space and through the eroded inferior capsule of the AC joint. This fluid sac gradually enlarges superiorly to present as a ganglion on top of the AC joint. It is important to recognize that the underlying pathology is not localized to the AC joint but reflects the more difficult problem of a full-thickness tear that is usually large. Palpation of the affected shoulder not uncommonly reveals AC tenderness especially if AC arthrosis is present. There is usually a palpable subdeltoid soft crepitation, which may represent a subacromial bursal fluid, a thickened bursa, or a torn tendon moving under the coracoacromial arch. A patient with subacromial impingement syndrome without rotator cuff tearing may have normal passive range of motion; however, it is not uncommon for a mild frozen shoulder to accompany this syndrome. In the latter case, there is usually some restriction of motion passively in forward elevation, external rotation, and internal rotation. In the presence of a fullthickness rotator cuff tear, passive range of motion is often remarkably normal, as joint fluid leaks out and lubricates the subacromial space.

On physical examination, a number of impingement signs are usually positive and are very helpful in documenting the diagnosis of subacromial impingement. These include a positive painful arc as the arm is lowered to the side from the fully overhead position, the classic impingement sign, pain with abduction in the plane of the scapula, and pain with internal rotation up behind the back. There may or may not be pain with resisted external rotation and resisted abduction. Active range of motion may be normal or may be reduced. A discrepancy between active and passive motion is highly suggestive of full-thickness disruption of the rotator cuff. A classic and most convincing clinical sign of a full-thickness cuff tear is weakness with external rotation. This is tested with the arm at the side and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. Both arms may be tested simultaneously. It is common, even in the presence of an isolated supraspinatus tear, to have demonstrable weakness of external rotation. The patient often can distinguish between lack of strength and the need to “let go” secondary to pain. In the larger tears of the rotator cuff, the patient often has so much external rotation weakness that he or she can neither initiate active motion of the arm nor maintain the arm in a position of external rotation in which it has been passively placed. In addition, a “lift-off” test has been described: The arm is brought behind the back, and an attempt is made to lift the hand off the small of the back. Inability to do this is highly suggestive of a subscapularis tear.

An alternative lift-off test for subscapularis insufficiency is the abdominal compression or “belly press” test, in which the hand is placed on the abdomen, the elbow is placed away from the side of the body and paramount to the hand, and the hand is pressed on the abdomen. Subscapularis insufficiency will result in the failure to maintain the elbow in the frontal plane, as the elbow folds into the side because of lack of internal rotation strength.

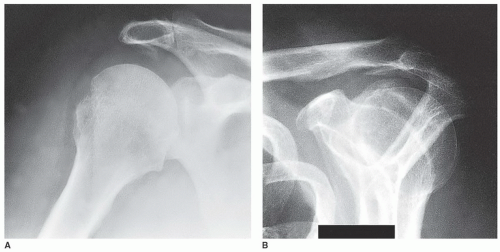

One of the most helpful radiographs in the diagnosis of subacromial impingement syndrome is an anteroposterior (AP) view of the shoulder in external rotation, which often reveals cystic changes, sclerosis, or bone reaction in the area of the greater tuberosity of the humerus. In addition, a subacromial traction spur may be identified and associated AC joint pathology may be present, as reflected by cystic changes, joint narrowing, or osteophyte formation. In the larger tears, this view often shows changes in the acromiohumeral interval, and in the most massive tears of long-standing duration, arthritic changes may be identified. Another AP view, with a 30-degree caudal tilt, will often more specifically show the anterior acromial spur; this view is used to outline the amount of acromion that projects anterior to the anterior edge of the AC joint, thought to be that amount of acromion pathologically projecting inferiorly. A lateral radiographic view of the scapula and acromion, with a 20-degree caudal tilt, has been termed the “outlet” view. This is intended to identify any bone projecting downward into the supraspinatus outlet, that space through which the supraspinatus passes. This view often identifies inferior protrusion of the acromion and the undersurface of the clavicle, and it may outline the shape of the acromion or an unfused acromial epiphysis. A supine axillary view is perhaps best to identify glenohumeral joint narrowing and the presence of an unfused acromial epiphysis. In a patient who has undergone previous surgery, this view also can reveal the amount of acromion that remains (Fig. 25-2).

If a rotator cuff tear is suspected, any one of a number of imaging studies may be utilized. The most common are arthrography, ultrasonography, and MRI. Arthrography is easily interpretable and can clearly define the presence or absence of a rotator cuff tear. Its disadvantages include that it is invasive, its helpfulness is usually limited to the identification of full-thickness tears only, and it rarely gives information about the quality of the tendon or the precise location of the tendons that are torn. Ultrasonography has been used to identify fullthickness tears, but it may have difficulty revealing small tears. In addition, small tears, partial tears, and even degenerative and scarred tissue may look similar. The reproducibility and high degree of accuracy that have been reported at some centers in this country and in Europe have not been uniformly reproduced in community hospitals and centers with less experience.

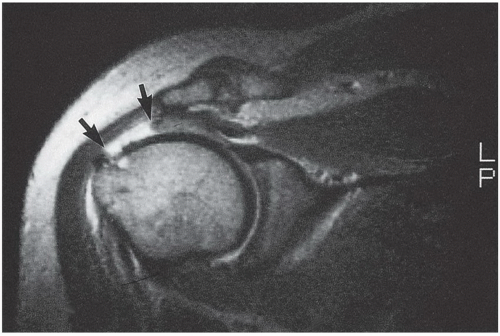

Although an MRI scan clearly gives the highest quality image of the shoulder and precise information about the extent and location of the tendon tear (Fig. 25-3) and may give information about associated biceps instability and associated muscle atrophy or fatty infiltration, its disadvantages include the fact that the patient may become claustrophobic and movement may interfere with MRI quality. In addition, the cost of an MRI scan is substantially greater than either of the other two imaging methods. However, for the most information and the clearest prognosis about surgical treatment and anticipated results, I prefer an MRI scan of the shoulder to identify the cuff pathology. For identification of tear extent, quality of remaining tissue, degree of muscle damage, and extent of associated pathology, there is no test that compares with a well-done and interpreted MRI, with or without contrast.

If a full-thickness rotator cuff tear has been documented, I tell the patient the following:

There is no evidence that once a full-thickness tear occurs, there is a potential to heal with exercise, immobilization, or medication.

Although the acuteness of the pain associated with a rotator cuff tear may subside in time, most patients remain symptomatic if they continue to try to use the arm, especially above chest or shoulder level.

Small tears often become larger over time. Although larger tears may not be more painful, they usually are associated with progressive weakness. Larger tears are more difficult to repair than smaller tears and often are associated with a higher failure rate when treated surgically.

A small percentage of patients with untreated rotator cuff tears may develop arthritis of the shoulder, the so-called cuff tear arthropathy. It is unknown how great this risk is.

If nonoperative treatment fails, and if symptoms warrant taking the risk of surgery, the best chance of successfully controlling the symptoms and restoring function is with surgical repair.

The results of surgical repair are much more predictable for pain relief than they are for return of strength. Even with surgical repair, patients who have high demand for the use of the shoulder, such as the overhead worker or manual laborer, may not be able to return to that type of job.

A certain percentage of surgically repaired tendons will either not heal primarily or may rupture again, with the estimates being anywhere from 5% to 15%. Most times, even if there is a rerupture of a tendon, if adequate decompression has been done, the symptoms do not require further surgery. The risk of rerupture tends to be higher with increasing age and with increasing tear size and is higher in the presence of comorbidities such as a smoking history, Parkinson disease, or a “weight-bearing” shoulder in patients with lower extremity ambulation-assistive devices.

SURGERY

The operation is done under either interscalene regional anesthesia or general anesthesia. Interscalene regional anesthesia can also be used in combination with endotracheal anesthesia for postoperative pain management.

In a mini-open rotator cuff repair, standard arthroscopic positioning, portals, and techniques are used for the complete glenohumeral joint inspection, as well as débridement of loose and torn tendon edges, greater tuberosity preparation, and arthroscopic subacromial decompression. After completion of the arthroscopic decompression, if minimal exposure is required, the standard lateral portal may be extended, subcutaneous flaps developed, and the deltoid split without detachment. With the rotation of the humerus, the torn supraspinatus can be brought into view and the standard repair accomplished with bone tunnels or suture anchors as a single or double row. My preference, however, even if a mini-open repair is going to be done using a deltoid split, is to use a standard anterior oblique incision similar to that described for the open technique. This places the incision in Langer lines and is more cosmetic than the extension of one of the arthroscopic portals (12).

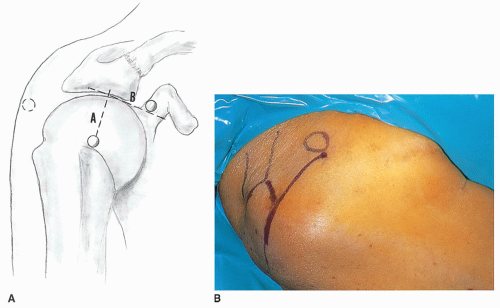

Once anesthetized, the patient is placed in a beach-chair position. The head is secured to the operating table and tilted slightly away from the affected shoulder, which helps provide space for retractors. A rolled-up towel is placed along the medial border of the scapula to stabilize it. The patient is positioned so that a line along the superior cortex of the acromion is perpendicular to the floor. In this way, during the acromioplasty, the osteotome or oscillating saw will be directed perpendicular to the floor, thus ensuring that the undersurface of the acromion will indeed be flat. The arm is draped free (Fig. 25-4). The hand is

covered with an elastic bandage or stockinette, up to the elbow. Prominent anatomic landmarks, such as the coracoid process, AC joint, posterolateral corner of the acromion, and lateral edge of the acromion, are identified.

covered with an elastic bandage or stockinette, up to the elbow. Prominent anatomic landmarks, such as the coracoid process, AC joint, posterolateral corner of the acromion, and lateral edge of the acromion, are identified.

The skin incision extends from just lateral to the coracoid process over the anterolateral corner of the acromion, ending just lateral to the acromion at a point halfway between the anterior and posterolateral corners of the acromion (Fig. 25-5). The length of the skin incision is typically 6 cm. The skin and subcutaneous tissue are infiltrated with a 1 to 500,000 concentration of epinephrine, which will minimize skin and subcutaneous bleeding (Fig. 25-6). Injecting the epinephrine solution in the area of the coracoacromial ligament and the AC joint also helps control troublesome bleeding in these areas. The subcutaneous tissue is divided down to the fascia investing the deltoid muscle (Fig. 25-7). It is helpful to avoid cutting into the fascia of the deltoid muscle, as this fascial envelope helps hold sutures for secure deltoid reattachment and minimizes fragmentation of the deltoid muscle during retraction. Flaps are developed in such a way that the entire superior AC joint may be palpated superiorly. They are undermined as far as the posterolateral corner of the acromion, and the anterior flap is undermined to a distance of at least 5 cm, which is the distance the deltoid muscle will be split. The deltoid muscle is split along the lines of its fibers in one of two areas. One split, in the raphe between the

anterior and middle deltoid, gives excellent exposure of the posterior cuff and is the direction of the split if the tear involves supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. If the tendon tear involves the subscapularis, particularly if the tear is large and retracted, I will often split the tendon instead at the level of the AC joint in line with its fibers. The split begins at a point on the anterior surface of the AC joint and extends distally a distance of approximately 5 cm (Fig. 25-8). Limiting the distance of the deltoid split to 5 cm avoids injuring the terminal branches of the axillary nerve. A no. 1 Tevdek suture marks the distal-most split in the deltoid so that during deltoid retraction the split will not be propagated. The deltoid muscle is bluntly dissected in line with its fibers through this 5-cm distance, until the whitish yellow bursa layer is identified. Bleeding is often present in the most proximal portion of the wound and is usually easily handled with electrocauterization. Adhesions under the deltoid often prevent insertion of retractors. It is usually helpful to use a blunt instrument or an index finger to break up adhesions under the medial and lateral deltoid flaps, so that retractors can be placed beneath the deltoid muscle. Deep fasciae of the deltoid often invest and adhere to the superior surface of the coracoacromial ligament. Using a sponge and a blunt retractor to sweep this off the coracoacromial ligament will isolate and identify this ligament for clear division or excision (Fig. 25-9). The acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery crosses the top portion of the coracoacromial ligament. Identification and cauterization of this troublesome bleeder before division of the ligament is helpful. The ligament is identified, isolated, and completely excised. Care must be taken to make sure that both anterior and posterior bands of the coracoacromial ligament are removed. This is done by clamping the coracoacromial ligament and using electrocautery or scissors along the lateral edge of the coracoid process to divide this ligament all the way to the base of the coracoid process (Fig. 25-10). Removal of the coracoacromial ligament can then be completed by retracting the deltoid out of the way and removing the ligament from the undersurface of the acromion.

anterior and middle deltoid, gives excellent exposure of the posterior cuff and is the direction of the split if the tear involves supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. If the tendon tear involves the subscapularis, particularly if the tear is large and retracted, I will often split the tendon instead at the level of the AC joint in line with its fibers. The split begins at a point on the anterior surface of the AC joint and extends distally a distance of approximately 5 cm (Fig. 25-8). Limiting the distance of the deltoid split to 5 cm avoids injuring the terminal branches of the axillary nerve. A no. 1 Tevdek suture marks the distal-most split in the deltoid so that during deltoid retraction the split will not be propagated. The deltoid muscle is bluntly dissected in line with its fibers through this 5-cm distance, until the whitish yellow bursa layer is identified. Bleeding is often present in the most proximal portion of the wound and is usually easily handled with electrocauterization. Adhesions under the deltoid often prevent insertion of retractors. It is usually helpful to use a blunt instrument or an index finger to break up adhesions under the medial and lateral deltoid flaps, so that retractors can be placed beneath the deltoid muscle. Deep fasciae of the deltoid often invest and adhere to the superior surface of the coracoacromial ligament. Using a sponge and a blunt retractor to sweep this off the coracoacromial ligament will isolate and identify this ligament for clear division or excision (Fig. 25-9). The acromial branch of the thoracoacromial artery crosses the top portion of the coracoacromial ligament. Identification and cauterization of this troublesome bleeder before division of the ligament is helpful. The ligament is identified, isolated, and completely excised. Care must be taken to make sure that both anterior and posterior bands of the coracoacromial ligament are removed. This is done by clamping the coracoacromial ligament and using electrocautery or scissors along the lateral edge of the coracoid process to divide this ligament all the way to the base of the coracoid process (Fig. 25-10). Removal of the coracoacromial ligament can then be completed by retracting the deltoid out of the way and removing the ligament from the undersurface of the acromion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree