Medial Collateral Ligament Sprain

Jess H. Lonner

Eric B. Smith

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The MCL is a strong stabilizing structure located on the medial side of the knee. It originates on the medial femoral epicondyle and inserts on the medial proximal tibia. The ligament is an important stabilizer against valgus stress. Patients with MCL sprain will usually have history of medial knee pain after trauma to the lateral side of the knee or lower leg or a fall with a valgus moment. Patients may also report of history of twisting injury with a “pop” or “snap” heard at the time of injury. Pain may be worse with weight bearing, and an effusion may be present. There may be a sense of knee instability or “giving way” with high-grade MCL sprains.

CLINICAL POINTS

A history of medial knee pain after trauma to the lateral side of the knee or lower leg is common.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is a significant stabilizer against valgus stress.

Knee instability may occur as a result of ligament injury.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients will have tenderness and possibly ecchymosis on the medial side of the knee extending from the medial femoral condyle to the proximal tibia. An effusion may be present. Pain will likely be elicited when a valgus stress is applied to the knee. Often, medial knee laxity with a valgus stress is most apparent at 20 to 30 degrees of knee flexion. With complete MCL tears, this laxity will be more pronounced than with partial tears. With isolated MCL tears, the knee will be stable to valgus stress at full extension; if it is not, multiligamentous disruption should be expected. It is important when examining patients with suspected MCL sprain to compare the injured extremity to the uninjured one with regard to medial laxity and medial opening with valgus stress (Fig. 18-1).

MCL sprains are graded on a three-point scale based on physical exam findings. A grade I sprain is characterized by medial knee tenderness, minimal swelling and ecchymosis, and no medial gapping when valgus stress is applied to the knee in slight flexion.

A grade II sprain demonstrates more pain and tenderness to palpation that can be localized to either the tibial or femoral insertion of the MCL or along its fibers, depending on where the sprain has taken place. Additionally, a discernible difference in the medial knee opening with valgus stress is noted when the injured leg is compared with the uninjured leg, usually gapping between 5 and 10 mm.

Grade III sprains are characterized by complete rupture of the MCL. In such injuries, knee joint swelling and effusion may be minimal, as much of the hemorrhage diffuses into the

soft tissues around the knee rather than into the knee joint. These injuries will demonstrate pronounced medial gapping (>10 mm) with valgus stress at 30 degrees of flexion. Isolated MCL sprains should yield a stable knee to valgus stress in full extension. However, if the knee does demonstrate medial gapping with full extension, concern should be raised for a cruciate ligament injury as well.1

soft tissues around the knee rather than into the knee joint. These injuries will demonstrate pronounced medial gapping (>10 mm) with valgus stress at 30 degrees of flexion. Isolated MCL sprains should yield a stable knee to valgus stress in full extension. However, if the knee does demonstrate medial gapping with full extension, concern should be raised for a cruciate ligament injury as well.1

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

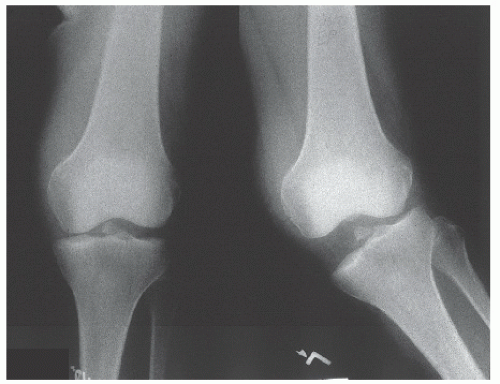

Diagnostic studies for suspected MCL injury include plain x-ray anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the affected knee. Patients with complete MCL rupture may show widening of the medial joint space on the AP view. Additional helpful views include valgus stress views of the affected knee (Fig. 18-2). These plain x-rays are performed with the knee in 15 to 20 degrees of flexion. The knee is given a valgus stress while the x-ray is performed similar to the force that caused the injury (Figs. 18-3 and 18-4). Pathologic laxity of the MCL will demonstrate a widened medial space of the knee joint.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree